Paris 1200 / Lionheart

PEROTIN & LEONIN. Chant and Polyphony from 12th Century France

medieval.org

Nimbus 5547

1998

1. Breves dies hominis [2:44]

2. Virtutum thronus frangitur [2:31]

3. Pange melos lacrimosum [3:44]

4. Te sanctum dominum [8:36]

5. Ave Maria fons letitie [1:28]

6. Ave virgo virginum [2:29]

7. Olim sudor Herculis [7:55]

CB 63

8. Condimentum nostre spei [5:36]

9. Sic mea fata [2:00]

CB 116 —

soloist: Kurt-Owen Richards, bass

10. Mundus vergens [2:42]

11. Mens fidem ~ Encontre ~ In odorem [5:39]

12. Gaude Maria virgo [9:13]

13. Veris ad imperia [1:31]

14. O curas hominum [5:12]

soloist: Kurt-Owen Richards, bass

15. Procurans odium [2:04]

CB 12

16. Diffusa est gratia [4:48]

17. Veste nuptiali [3:08]

soloist: Stephen Rosser, tenor

18. Mors vite propitia [2:32]

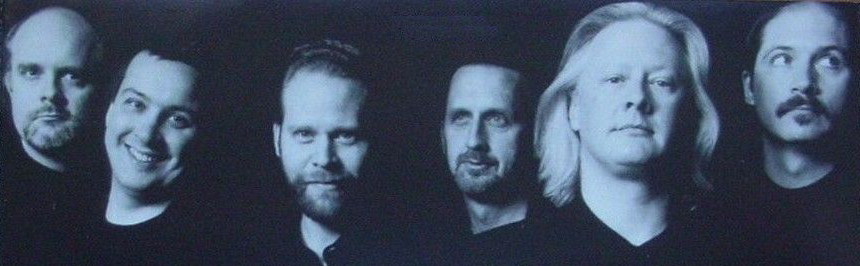

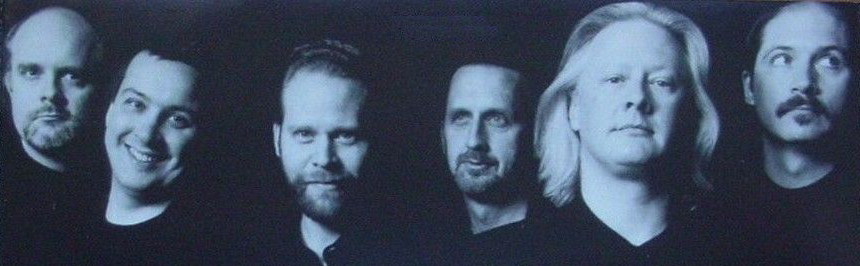

LIONHEART

Jeffrey Johnson • Lawrence Lipnik

Kurt-Owen Richards • John Olund

Richard Porterfield • Stephen Rosser

Acclaimed for their exquisite blend and intonation, the men of

LIONHEART have established themselves as leading exponents in the field

of a cappella singing. Featuring Gregorian chant as the keystone

of its repertoire, Lionheart brings its varied repertoire (medieval,

Renaissance and contemporary works) to life with unique artistic

expressiveness. Critics across America, from The Los Angeles Times to

The New York Times, have hailed this ensemble for its spirited

programming and exquisite artistry. Also recognized for their

personable immediacy as performers and international performing

expertise, Lionheart has amassed an impressive list of credentials in

the four short years of its existence: Lincoln Center, Weill Recital

Hall at Carnegie Hall with Steve Reich, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

at the Cloisters, the Folger Library in Washington D.C., the Cleveland

Museum of Art, National Public Radio's "Performance Today," and major

venues across the United States as well as their own self-produced

concert series in New York City, where they make their home. More

information on Lionheart is available on their website

http://www.chantboy.com/lionheart.

Lionheart's debut recording with Nimbus: "My Fayre Ladye" - Tudor Songs

and Chant (NI5512) includes works by Dunstable, Cornysh, Browne and

Pygott.

Translation of Pange melos lacrimosum by Tom Baker

All other translations by Richard Porterfield. All notes and transalations © 1998 Lionheart

Recorded by Nimbus Records,

Wyastone Leys, Monmouth NP5 3SR, UK

Cover: Gargoyles, Notre Dame de Paris, France

Courtesy of Tony Stone Images, London.

℗ 1998 Wyastone Estate Limited

© 1998 Nimbus Records Limited

http://www.wyastone.co.uk

A Digital Recording. Recorded at Leominster Priory on 18-22 August 1997.

Manufactured in the UK

Cultures

struggling through a nebulous period of transition are known to break

out of the old order by bold, creative leaps into the unknown. These new

creative acts, send a hopeful signal to a society of impending cultural

transformation. Paris at the turn of the thirteenth century was such a

bellwether society.

It is well documented and understood that

medieval life was severe and nearly unendurable. Medieval people must

have yearned for respite from the confusion and turmoil of this dark

age. Some found solace and safety in monasteries. Between 1066 and 1154

(A.D.) the number of monasteries grew from 48 to almost 500. The number

of monks expanded from 900 to well over 5000. The secure, cloistered

refuge of the monastery cultivated a mixture of ritual action and

ascetic examination. Consequently, the monks' responses to the age-old

questions of human purpose were transformed by this combination of

contemplative rites. With the advent of pilgrimage roads, the

formulation of that inquiry was further nurtured by diverse strains of

behavior and intellectual thought from all over the known western world.

In

the middle of the twelfth century a surprising period of prosperity

occurred bringing population expansion, new classes of people, new

tensions and new layers of civilized discontent A sudden burst of social

evolution transpired. More leisure time for socialization induced a

higher sensitivity to nature and a belief in supernatural phenomena,

marvels and the fantastic: the miraculous power of the Divine often in

opposition to the diabolical magic of Satan. An interest in alchemy and

mathematics ensued, attempting to quantify these forces. As a result, a

synergy of ancient truths and a new social decorum inaugurated a time of

renewed vigour for a life of the spirit and the mind.

In the

midst of this cultural turbulence a small collection of monks entered

the early pagan worship grounds in the area of the Ile-de-la-Cite in

what is now Paris. These men began erecting a church which reflected the

synthesis of their revelatory thought. The catalyst driving these

descendants of the great Frankish leader Clovis was a dark, profound

mysticism. This mysticism measured man not by and of himself or anything

known in his world, but by the touchstones of infinity and etemity. Its

magnetic essence, fathomed in the confines of humble isolation, was one

imagining a power beyond oneself. These men believed that a mystical

soul given over to darkness and negation could, through absorption in

the Divine, rise above reason and self-consciousness to light,

revelation, true knowledge, healing and metamorphosis.

The new

Cathedral of Notre Dame was the vessel for their austere passion. The

Abbot Suger, often cited as an initiator of innovative architectural

design in this period, dared to excite believers with his dictum "de materialilbus ad materialia",

"from material to the immaterial". Using sacred geometric proportions,

line and ratios, Abbot Suger and his modest exponents envisioned a

structure which reinvented the concept of the sacred space. Its

foundation and ingenious flying buttresses provided a firm support for

new pointed arches and six ribbed vaulting. The interior space served as

a ritual setting for a subtle interplay of light and colour manifest in

brilliant red and blue stained glass windows. Music collected and

performed here acutely mirrored the circular structure of the

architectural scheme, enlarging to early polyphony from a basis in

chant. The age-old desire to tell a vivid story through sound was

expressed through the consonances of divine proportion.

Works of

vibrant imagination in the mechanical arts also flourished. Indeed, the

word imagination first appeared in Old French in the twelfth century.

Mostly unnamed but ardent designers/builders/religious men generated

this balanced art and architecture, now referred to as Gothic. The

musical selections presented here reflect a Gothic Paris emerging from

an era of struggle with a new architecture of thought and expression.

In

our present day, exciting new technologies embody the same yearning,

spiritual impulses exhibited in the visionary building of Notre Dame

Cathedral. The primitive urge for experience beyond the plane of routine

existence endures; the contemporary extension of science presents its

own set of gothic questions about the design of tomorrow. Much like the

late twelfth century trascendental clerics must have thought, the

solutions to the unknown must hover high above the resolute towers of

Notre Dame of Paris: her girded spires reach incompletely skyward, our

imaginations inevitably lifting us toward the promising illuminations of

a new time.

Jeffrey Johnson

The

three main types of composition on the presente programme are organum,

motet and conduct. Organum ist a technique, first described in the

treatises of the tenth century, of adding new voices to a given piece of

plainchant. The simplest kind of organum consist of a voice moving in

parallel with the chant melody at a fixed harmonic distance. Medieval

singers were adept at improvising this parallel organum, as well as

other primitive organal techniques, to decorate a given melody. Lionheart employs some ot these devices in its performance of Breve dies hominis,

and on other monophonic pieces on this recording. The added voices are

not indicated in the original music; the ensemble develops these organum

arrangements in rehearsal according to well-known principles of

medieval composition and by allowing some free rein to the imagination.

Choirs

at Notre Dame Cathedral, and at other and monasteries in twelfth

century France, developed a more complex species of composition known as

florid organum. By unnaturally lengthening each note of the

plainchant, they allowed the organal voice time to execute any number of

decorative melodic figures around and about the chant line. A phrase

that might be sung in a few seconds of plainchant could thus expand into

a clausula (a musical unit of organum) lasting a minute or longer. The voice sustaining the lengthened tones of the chant is called the tenor (from the Latin tenere - to hold). The faster moving newly composed organal voice is called the duplum (doubling voice).

The

structure of an organum setting depends on the plainchant it decorates

and magnifies. Only those sections of the chant given to the soloists

and leaders of the choir receive organal treatment. The sections of

chant for the full choir remain unadorned, and the chant proceeds at its

normal pace. Furthermore, within organum sections, when the chant line

produces a string of many notes on a single syllable (a melisma

- from the Latin word for honey), the organum tenor stops holding long

notes, and begin to move at a steady marching tempo, about as fast as

the duplum. This style is called discant. A section of organum in this style, then, is a discant clausula. The organum setting of the responsory chant Te sanctum dominum contains a discant clausula in the verse (Cherubin quoque et seraphin) and again in the doxology (Gloria patri et filio et spiritui sancto).

Medieval

poets took the opportunity afforded by the discant clausula, which has

many notes and only a few syllables of text, to supply the duplum with

completely new text. These new words seldom have any direct relation to

the text of the chant. A discant clausula performed on its own with a

new poetic text is called a motet. The process of its creation

is basically a matter of fitting poetry to music that already exists -

as when a modern lyricisist makes a song out of an instrumental melody.

The music of the motet Ave Maria fons letitie is a

clausula from a setting of the Alleluia chant for Easter Sunday. The

lyric for the most part sets one syllable per note. In the parent

organum (the Alleluia), the clausula sets only one syllable, the la of the word immolatus.

If the parent organum is a setting for three voices (organum triplum) quite often the motet will supply the duplum with a text in Latin, and the third voice (the triplum) with one in the vernacular. In the motet Mens fidem/Encontre/In odorem

the duplum sings a moralizing Latin text, the triplum sings a French

song about the love of a fair maid, and the tenor sings a long melisma

from an Alleluia chant in honour of Saint Andrew.

Conductus

refers to a piece of vocal music which is not based on chant. The term,

which could be translated "leading together" has been thought to

suggest a piece that served for processions during church services. It

is more likely that the name is derived from the free voice-leading.

i.e. the melody leading itself, instead of following the lead of a

chant, as organum does. Still, the style of the conductcs repertoire

betrays its origin in organum technique. The voices in a conductus of

two or more parts employ the same rhythmic structures and simultaneous

articulation of a single text that one finds in organum. Also, the

harmonic and contrapuntal language of conductus is based upon organum

practice. The difference is that in organum, the chant is the master,

and the organal voices follow faithfully. In conductus, the voices share

the leadership more or less equally.

Monophonic conductus

constitutes a type within the genre whose distinguishing feature is its

single melodic line. The monophonic conductus thus presents a number of

questions for scholars to debate and for performers to consider

critically. The principal problem arises in connection with the

interpretation of an ambiguous notation of rhythm. Composers of organum

and conductus used a notation borrowed from plainchant, which by the

twelfth century proceeded in equal or near equal rhythmic values,

without a regularly recurring pattern of stress. The resulting chant

rhythm is rhapsodic and asymmetrical. By contrast, polyphonic conduct

uses precise long and short values organized through repetition into a

clear and predictable metre. This clarifies the harmonic relationships

between voices, and also helps the performers stay together in

multi-part music. However, the same notational symbols served to record

both kinds of rhythm. Presumably, the singers were expected to know

which system to use based on the context of the music. My transcriptions

of Sic mea fata and Olim sudor Herculis invite a chant-like interpretafion, but when there is clear repetition of a short melodic figure, as in the opening verse of Olim sudor Herculis,

it is only natural to slip into a pattern of long and short values. A

soloist can easily move back and forth between the two modes of

delivery; perhaps the medieval singer also exercised discretion in this

regard.

The same question arises with organum duplum in which a vocal line is set against the sustained notes of the chant (Te sanctum dominum).

Here there is little difficulty in keeping the voices together, and so a

rigidly metrical interpretation is not necessary for practical

performance. A free, rhapsodic solo line can produce impressive results.

For this recording, however, Lionheart found a generally

metric interpretation most convincing. This method allows the soloist

freedom to manipulate the tempo, whilst maintaining clarity and drive

throughout.

Organum duplum is sometimes called organum purum

(pure organum) and sometimes "Leonine" organum after the composer

Leonin, who may have invented it. The question of authorship, however,

remains unclear for most of the organum repertoire. The three-part

setting of the Alleluia verse Diffusa est gratia is one

of seven works which the medieval theorist known to scholars as

'Anonymous IV' attributed to "Magister Perotinus" (Master Perotin). An

Englishman writing in the second half of the thirteenth century,

Anonymous IV only passed on what he had been told about Perotin, and his

predecessor, Leonin: namely that Perofin re-wrote many parts of the

"great book of organum" which Leonin had made, and that this corpus of

music was still in use at the Cathedral of Notre Dame when Anonymous IV

was writing. Also, that Leonin excelled at organum purum. whereas

Perotin was considered the best at writing discant. Was the theorist in

fact speaking literally of two individuals, or perhaps figuratively,

about two styles of composition practised by two generations of

composers? Who else may have contributed compositions to the repertoire,

when and where? Just because the music was in use at Notre Dame

Cathedral does not rule out the possibility that some of it might have

come from elsewhere. Until more evidence comes to light, there is unsure

means of assigning authorship to most of the repertoire. Therefore,

although there is a strong chance that Perotin may have written the

three-part organum Gaude Maria virgo, it is by no means

a certainty. Even if Anonymous IV is to be taken at his word, he does

not say that Leonin never wrote three-part organum, or that Perotin

never wrote the two-part species. Anonymous IV simply states that by his

own time, each was considered the best at a certain style, and that one

rewrote the work of another.

The following chart illustrates the way in which the musical genres developed from the plainchant,

|

|

Plainchant |

—————————

|

|

|

|

|

Organum technique |

—————————

|

|

|

|

|

Poetry |

| Poetry |

—————————

|

|

|

|

|

Organum repertoire |

|

Conductus |

|

|

Motet |

|

|

|

|

Plainchant combined with organum technique produces the

organum repertoire. Poetry applied to the organum repertoire

(specifically the discant clausula) form the motet. Poetry and organum

technique combine to produce conductus.

The parallel motion of

perfect intervals (octaves, fourths and fifths) which results from

organum technique forms the basis of early medieval counterpoint. By the

fourteenth century other intervals began to assume more prominence, and

from the sixteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, composers

carefully avoided parallel fifths and octaves, which they considered

serious defects in composition. Indeed, such progressions sound awkward

and out of place in the sophisticated styles of Palestrina, Bach and

Mozart. Nevertheless these raw and undomesticated harmonic relationships

never left folk music, and are the source of the power in the "power

chords" of rock and roll. The music that rang through Notre Dame in the

years surrounding 1200 revelled in that power - perhaps as an image of

the untamable power of God.

Richard Porterfield