El viaje del navegante / Locus Musicus

Cantos y danzas de la Edad Media

medieval.org

Verso VRS 2031

2005

La crisis de la mitad de la vida

1. Media vita in morte sumus [4:06] responsorio, s. IX

La marcha

2. Lamento di Tristano/La Rotta [4:20] instrumental, anónimo italiano, s. XIV

3. Chevalier mult estes guariz [4:55] canción de cruzada, anónimo francés, s. XII

Cantos de añoranza de la amada

4. Mia irmana fremosa [3:16]

Martin CODAX, s. XIII · canción de amigo

ca III

5. Ai deus, se s'abora meu amigo [3:29]

Martin CODAX, s. XIII · canción de amigo

ca IV

6. Chanterai por mon corage [6:27]

Guiot de DIJON, s. XII · canción de cruzada

7. La Septime Estampie Real [1:29] instrumental, anónimo francés, s. XIII

Diálogo con el mar

8. Ai ondas que eu vin vere [2:49]

Martin CODAX, s. XIII · canción de amigo

ca VII

9. Ondas do mar de Vigo [4:08]

Martin CODAX, s. XIII · canción de amigo

ca I

10. La Uitieme Estampie Real [1:48] instrumental, anónimo francés, s. XIII

El encuentro con los demonios internos

11. Ben pode Santa María [5:05] Cantiga de Santa María n° 189, s. XIII

CSM 189

12. Trotto/Saltarello [3:13] instrumental, anónimo italiano, s. XIV

La súplica por la salvación

13. Veni Creator Spiritus [3:04] himno, invocación al Espiritu Santo

14. Santa María, strela do día [4:15] Cantiga de Santa María n° 100, s. XIII

CSM 100

15. La Quinte Estampie Real [2:25] instrumental, anónimo francés, s. XIII

El regreso

16. Mandad'ei comigo [1:42]

Martin CODAX, s. XIII · canción de amigo

ca II

17. Quantas sabedes amar amigo [2:52]

Martin CODAX, s. XIII · canción de amigo

ca V

18. Dansse Real [1:03] instrumental, anónimo francés, s. XIII

Locus Musicus

Carlos Zumajo Galdón

Elena Gómez Trigo — voz

Carlos Zumajo Galdón — flauta travesera medieval, gaita

Laureano Estepa García-Bravo — vihuela de arco

Eduardo Moreno Vega — percusión

Colaboradores:

Yurena Duque Zumajo, Sofía Alegre,

Asunción Tarrasó Alcalá y Eduardo Aguirre de Cárcer

English liner notes

El viaje del navegante

Cantos y danzas de la Edad Media

El

viaje de héroe, presente en cualquier mitología, desde las grandes

epopeyas hasta los cuentos de hadas, es una metáfora del camino

interior, es decir del proceso de autoconocimiento a través del cual una

persona (el héroe o, como diríamos hoy, el buscador) sufre una crisis

de cualquier tipo (pérdidas afectivas, enfermedad, disgusto con su

vida...) que le hace cuestionarse y plantearse cambios (de valores, de

vida...) dejando algo de lo conocido para abrirse a lo nuevo ignoto. La

hondura de este proceso depende del compromiso del buscador, que puede

hacer movimientos puramente externos (un cambio de trabajo, por ejemplo)

o sufrir una profunda transformación psicoespiritual. En cualquier caso

serán inevitables las pruebas, las renuncias, el dolor y la

incertidumbre, como tan bellamente nos cuentan los relatos heroicos de

Hércules,

Moisés o los Caballeros de la Tabla Redonda.

Resumiendo

y simplificando algo que precisamente se caracteriza por su riqueza

simbólica, podríamos decir que existe un héroe guerrero, solar y

patriarcal, que debe enfrentarse al dragón (los obstáculos interiores

como pueden ser la cobardía, la falta de autenticidad, la

autocomplacencia...) para rescatar a la princesa (el alma, la esencia de

sí).

Pero existe también un héroe navegante, lunar y femenino, a

la búsqueda de la maduración emocional, cuyo viaje transcurre por las

aguas de lo afectivo, que han de guiarle a su propio corazón. No es el

héroe juvenil que debe retarse y vencer, sino el buscador con más años y

más experiencia, más receptivo a los sentimientos y por ello más cerca

de su lado femenino. Así lo podemos comprobar en la selección de

canciones que nos brinda Locus Musicus, donde tan presente está la

amada, la madre, la virgen Santa María.., y a través de estas figuras,

la conexión con la añoranza, la inseguridad, el anhelo, el amor. Valores

todos ellos que seguramente no defienda ni enarbole el guerrero

convencional, pero que rescatan otro tipo de sabiduría: lo que se

aprende no en la ida sino en la vuelta, como el viaje de Ulises: excelso

guerrero en la salida hacia Troya, conmovedor navegante en el regreso a

Itaca.

PACO PEÑARRUBIA

O voi ch'avette li'ntelletti sani,

mirate la doctrina che s'asconde

sotto'l velame de li versi starnsi.1

Infierno, Canto IX. La divina comedia.

Dante Alighieri

Al

igual que Dante con estos hermosos versos invita al lector a dejarse

guiar por un mundo simbólico en el que nada es lo que parece, proponemos

al oyente este viaje sonoro.

Detrás de los versos y de su

perfección rítmica busquemos misterios y alegorías, nuestra propia

historia secreta dentro de este círculo programático en el que todo

cambia y al mismo tiempo todo permanece, y desde cualquier punto del

mismo iniciémoslo una y otra vez.

El navegante de nuestra

historia inicia su periplo en el mismo punto que el héroe de Dante, en

torno a los 35 años que actualmente asociaríamos a la "crisis de los

40". Es la crisis de la mitad de la vida.

Cuenta la leyenda que Notker escribió Media vita in morte sumus cuando vio a un

albañil

que perdía el equilibrio y pensó: "estamos muertos en mitad de la

vida". Este responsorio del siglo IX fue atribuido al monje Notker

Balbulus —Notker el tartamudo— (ca. 840-912) debido a sus continuas

reflexiones sobre la unidad entre lo humano y lo divino, el cielo y la

tierra, la vida y la muerte. Probablemente perteneciera al canto

galicano y pasara a formar parte del canto romano, hasta alcanzar el

rango de canción folklórica eclesiástica. Cuando en el ario 1263 el

arzobispo de Treves nombró a un tal William como abad del monasterio de

St. Matthias contra la voluntad de los monjes, éstos se postraron en el

suelo y entonaron el Media Vita para recibir la protección del

abad confiriendo al responsorio facultades milagrosas. En el Concilio de

Colonia de 1316 se prohibió cantar Media Vita sin el permiso de un obispo.

Después de la crisis, el sentimiento de carencia, la marcha: comienza el camino de búsqueda. Para ello, el Lamento di Tristano/La Rotta,

danzas italianas pertenecientes al manuscrito que se conserva en la

Biblioteca Británica de Londres, cuya fecha aproximada de elaboración

Gilbert Reany sitúa entre 1390 y los primeros arios del siglo XV en el

Norte de Italia, con el que queremos mostrar la tristeza del que se va y

a la vez lo irrevocable de la decisión de partir. A continuación, una

canción de cruzada del siglo XII de un desconocido trovero

(músicos-poetas del norte de Francia) Chevalier mult estes guariz,

que aparece en un manuscrito de la Biblioteca Amploniana de Erfurth.

Una llamada a la resistencia de los cristianos ricos para que sigan el

ejemplo de Luis y se sumen a la lucha por recuperar los Santos Lugares

tomados por los infieles. Nuestro héroe asume el riesgo de perderlo

todo, casa, tierras y, sobre todo, el orgullo. Deja todo y camina hacia

el paraíso, lo que le permitirá alcanzar la visión máxima con la

sabiduría y la verdad. El encuentro con las olas le une

irremediablemente con el mundo que ha dejado en tierra y con su propia

zozobra interna.

Los cantos de añoranza de la amada son dos cantigas de amigo de Martin Codax, y una chanson del trovero Guiot de Dijon. Las tres en labios de mujer. Sin contar las cantigas

de Santa María, de las 1757 cantigas en lengua galaico-portuguesa que

se conservan de unos cien poetas, solo estas seis tienen música. En 1914

Pedro Vindel, un librero anticuario de Madrid, encontró el manuscrito

en un pergamino de un solo folio utilizado como forro de un libro de

Cicerón ("De oficiis"). Este trascendental hallazgo se hizo público en la Revista de Arte Español bajo el título: Importante descubrimiento.

En 1915 apareció el libro con una tirada de sólo diez ejemplares. En

1977 el manuscrito fue adquirido por la Piermont Morgan Library de Nueva

York. La hoja tenía consignado en la cabecera el nombre de Martin

Codax. Algunos han querido ver aquí la prueba inconcusa de la existencia

de las hojas volantes, que el trovador regalaba a su amada.

Pero,¿quién

fue Martin Codax?. Mucho se ha especulado sobre el nombre del trovador.

Es posible que Codax sea un apodo cuyo significado desconocemos. Podría

ser oriundo de Galicia, Portugal, Castilla o León ya que en toda esta

área geográfica se cultivaba la canción trovadoresca en

galaico-portugués. Por hablar de Vigo cabe suponer que fuera de allí o

tuviera alguna vinculación con esta ciudad. En estos sencillos versos se

utiliza la técnica del leixapren (toma-deja), redondeando la forma y transportando al oyente hacia un estado casi meditativo. El Amigo es el amante confeso, del cual son cómplices la madre y las irmanas (amigas íntimas). En Mia irmana fremosa la enamorada pide a su irmana

que le acompañe a mirar las olas del mar agitado (su mente y su corazón

también están en este estado) para esperar a su madre y a su amigo. Ai deus, se s'abora meu amigo

es una cantiga de una inmensa tristeza donde se expresa el sentimiento

de soledad de una forma tremendamente desgarradora. El texto de la

canción de cruzada Chanterai por mon corage expresa las

cuitas de una mujer que espera a su amado ausente por peregrinaje, y

canta para calmar su corazón con el anhelo de que el suave viento le

devuelva al amigo, en tanto se alivia, cuando el amor le oprime por las

noches, tapando su cuerpo desnudo con una de las camisas que el le

envió. Finaliza con La Septime Estampie Real, que

pertenece al manuscrito de la Biblioteca Nacional de París conocido como

"Chansonnier du Roi". Data de la segunda mitad del siglo XIII. A este

mismo manuscrito pertenecen el resto de las estampies.

La añoranza invade a la amada que dialoga con el mar entonando dos nuevas cantigas de Martin Codax. Ai ondas que eu vin ver abunda en el sentimiento de soledad que experimenta una persona enamorada cuando su amor no está cerca. En Ondas do mar de Vigo

esa soledad se expresa en el diálogo con las olas del mar. Son las olas

del mar las que nos llevan hacia el héroe de esta historia situado en

cualquier punto del océano de las emociones. En todo viaje surgen las

dificultades y, en el camino, nuestro navegante ha de luchar contra sus

demonios internos.

Ben pode Santa María (cantiga

de Santa María n. 189 perteneciente al manuscrito de El Escorial, donde

aún se conserva) narra el encuentro de un hombre en peregrinación con

un dragón al que da muerte. Lo interpretamos como símbolo de lucha

interna contra los fantasmas de la razón (el dragón y la enfermedad) y

de la sanación a través de la emoción (el llanto) y la humildad (la

oración). El Trotto y el Saltarello

pertenecen al mismo manuscrito de las danzas italianas mencionadas

arriba. El ritmo de este último anticipa las tarantelas del siglo XVI

(danza frenética en 6/8) utilizadas para purgar la picadura y expulsar

el veneno de la tarántula y así purificar el alma y el cuerpo.

El ultimo paso en el ejercicio de humildad es la súplica por la salvación. El conocidísimo himno Veni Creator Spiritus, de invocación al Espiritu Santo, pertenece al Graduale Triplex, publicado por los monjes de Solesmes.

La cantiga de loor n° 100 Santa María, strela do día

refleja la súplica de los hombres a la Virgen para que les muestre el

camino de alcanzar el paraíso y el perdón de sus pecados. En nuestro

programa marca la necesidad del retorno al punto de partida pero con

toda la madurez de la experiencia.

Con la cantiga de Martin Codax Mandad'ei comigo la amada anuncia el regreso con un mensaje que "traigo comigo": llega sano y vivo. Quantas sabedes amar amigo,

lo celebra con todas las mujeres que conocen el amor, bañándose

exultantes en las aguas de Vigo. Como colofón, la alegría de la Dansse Real francesa, interpretada con gaita y pandero.

1 Oh los que habéis entendimientos sanos, notad

lo que se esconde de enseñanza de este mi oscuro verso en los

arcanos!

ELENA GÓMEZ Y CARLOS ZUMAJO

Voyage of the traveller

Songs and dances from the Middle Ages

The

hero's travels, present in all mythologies from the great epics to

fairy tales, are a metaphor for the inner journey, that is the process

of self-knowledge through which a person (a hero or, as we would say

today, a seeker) suffers a crisis of some sort (loss of affection,

sickness, disappointment with life ...) whereby they question themselves

and think about changes (of values, living ...) abandoning something of

the known to open to the new and unknown. The depth of this process

depends on the searcher's commitment, which may lead to purely external

movements (change of job, for example), or to a profound

psycho-spiritual transformation. In any event, trials, relinquishment,

pain and uncertainty will be inevitable, as so beautifully told to us in

the heroic tales of Hercules, Moses or the Knights of the Round Table.

Summarising

and simplifying something characterised precisely by its symbolic

richness, it could be said that there is a warrior hero, solar and

patriarchal, who must confront the dragon (internal obstacles like

cowardice, lack of authenticity, self-satisfaction ...) to rescue the

princess (the soul, the essence of self).

But there is also a

seafaring hero, lunar and feminine, seeking emotional maturity, who

travels through the waters of affection, which must take them to their

own heart. This is not the youthful hero who must challenge and

overcome, but rather the seeker, of more years and more experience, more

receptive to feelings and so closer to their feminine side, as can be

seen in the selection of songs Locus Musicus offers us, where the

beloved, mother, the Virgin Mary, are so present ... and, through them,

the connection with yearning, uncertainty, longing, love. Surely the

conventional warrior does not defend or represent these values, although

they liberate another form of wisdom: what is learned not on the

outward voyage but on the way back, as in the voyage of Ulysses —

sublime warrior on departure for Troy and moving seafarer on the return

to Ithaca.

PACO PEÑARRUBIA

O voi ch'avette l'intelletti sani,

mirate la doctrina che s'asconde

sotto'l velame de li versi starnsi.1

Inferno, Canto IX. La Divina Commedia.

Dante Alighieri

Just

like Dante who, with these beautiful lines, invites the reader to allow

him or herself to be guided by a symbolic world, where nothing is what

it appears to be, we propose this sonorous voyage to the listener.

Behind

the verses and their rhythmic perfection, we seek mysteries and

allegories, our own secret history within this programmatic circle where

everything changes yet all remains and which, from any point, we can

begin it time and again.

The traveller of our tale begins his

wanderings at the same point as Dante's hero, at about age 35, currently

associated with the "crisis of 40", the half-life crisis.

According to legend, Notker wrote Media vita in morte sumus

on seeing a bricklayer lose balance, and thinking, "in the midst of

life we are dead". This ninth century response was attributed to the

monk Notker Balbulus — Notker the stammerer — (ca. 840- 912) because of

his continuous reflection on the unity between the human and the divine,

heaven and earth, life and death. It probably belonged to Gallican

chant and became a part of Roman chant until attaining the status of a

song of ecclesiastic folklore. When, in 1263, the Archbishop of Treves

appointed William as the Abbot of the monastery of St. Matthias, against

the monks' wishes, they prostrated themselves on the ground and intoned

the Media Vita to receive the abbot's protection, conferring miraculous faculties upon the responsory. At the 1316 Cologne Council, singing Media Vita without permission from a bishop was prohibited.

Following the crisis, the sensation of lack, departure: the search begins. For this, the Lamento di Tristano/La Rotta,

Italian dances from the manuscript conserved in the British Library in

London, dated by Gilbert Reany approximately between 1390 and the first

years of the fifteenth century in Northern Italy, and with which we wish

to show the sadness of the one leaving and, at the same time, the

irrevocable nature of the decision to leave. Then a song from the

twelfth century crusade by an unknown trouvere (Northern French

musician-poets) Chevalier mult estes guariz, which appears

in a manuscript in the Amploniana Library in Erfurt. A call to

resistance of wealthy Christians to follow the example of Louis and join

the struggle to recover the Holy Places taken by the infidels. Our hero

assumes the risk of losing everything — home, land and, above all,

pride, leaving all behind and heading for paradise, which will enable

the maximum vision to be attained, with wisdom and truth. The encounter

with the waves unites him irrevocably with the world he left behind and

with his own internal unease.

Songs of yearning for the beloved take the form of two cantigas de amigo of Martín Codax, and a chanson of the trouvere Guiot de Dijon, the three of them from the lips of women. Not including the Santa María cantigas, of the 1757 cantigas

conserved in Galician-Portuguese, by about a hundred poets, only these

six have music. In 1914, Pedro Vindel, an antiquarian bookseller in

Madrid, found the manuscript on a one-page parchment used to line a book

by Cicero ("De oficiis"). This transcendental find was made public in the Revista de Arte Español (Spanish Art Journal) under the heading Major discovery.

In 1915, the book came out, in a print of just ten. The manuscript was

acquired in 1977 by the Piermont Morgan Library of New York. The heading

to the page contained the name of Martin Codax. Some have wished to see

this as irrefutable proof of the existence of missives the troubador

sent his beloved as a gift.

But who was Martin Codax? There has

been speculation about the troubador's name. It is possible that Codax

is a nickname whose meaning we do not know. He may have been from

Galicia, Portugal, Castile or Leon, since the troubador song in

Galician-Portuguese was cultivated throughout this geographical area.

With the mention of Vigo, it can be assumed that he was from there, or

had some link with this city. These simple verses use the technique of leixapren (leaving/taking), rounding out the form and transporting the listener to an almost meditative state. The Amigo is the confessed lover, whose accomplices are the mother and the irmanas (intimate female friends). In Mia irmana fremosa,

the beloved asks her "irmana" to accompany her to look at the waves of

the troubled sea (her mind and heart also in such state) to await her

mother and the friend. Ai deus, se s'abora meu amigo is a cantiga of extreme sadness, expressing the feeling of solitude in a deeply heartbreaking way. The text of the crusade song Chanterai por mon corage

expresses the troubles of a woman who awaits her beloved, away on a

pilgrimage, and sings to quiet her heart in the hope that the gentle

wind will bring her amigo back to her, as she seeks relief, when

love oppresses her at night, covering her naked body with one of the

chemises he has sent her. Finally, La Septime Estampie Real,

from the manuscript in the National Library in Paris known as the

"Chansonnier du Roi", dating from the second half of the thirteenth

century. The other estampies also belong to this manuscript.

Yearning fills the beloved who dialogues with the sea, singing two new Martín Codax cantigas. Ai ondas que eu vin ver abounds in the feeling of solitude of a person in love when the loved one is not near. In Ondas do mar de Vigo,

that solitude is expressed in the dialogue with the waves of the sea,

the waves which carry us toward the hero of this tale, to be found at

some point in the ocean of emotions. Difficulties arise in any journey

and, along the way, our traveller has to struggle against his inner

demons.

Ben pode Santa Maria (Santa María cantiga

No. 189 from the manuscript in El Escorial where it is still conserved)

narrates the encounter of a man on a pilgrimage with a dragon which he

kills. This is interpreted as a symbol of the internal struggle against

the ghosts of reason (the dragon and sickness) and of cure through

emotion (lament) and humility (prayer). The Trotto and the Saltarello

are from the manuscript of Italian dances already mentioned. The rhythm

of the latter anticipates sixteenth century tarantellas (a frenzied

dance in 6/8) used to purge the bite and expel the poison of the

tarantula and so purify body and soul.

The last step in the exercise of humility is the entreaty for salvation. The very familiar hymn Veni Creator Spiritus, invoking the Holy Spirit, belongs to the Graduale Triplex published by the monks of Solesmes.

The praise cantiga No. 100 Santa Maria, strela do dia

reflects the petition of men to the Virgin to show them the way to

attain paradise, and pardon for their sins. In our program, it defines

the need to return to the point of departure but with all the maturity

of experience.

With the Martin Codax cantiga Mandad'ei comigo, the beloved announces the return with a message which "I bring with me": he arrives safe and sound. Quantas sabedes amar amigo celebrates it with all women who know love, bathing exultantly in the waters of Vigo. As culmination, the joy of the French Dansse Real played on bagpipe and tambourine.

1 Oh you of sound understanding, note the learning hidden under the veil of enigmatic verses!

ELENA GÓMEZ Y CARLOS ZUMAJO

Translation: Gordon Burt

Bibliografia

· Abbaye Saint Pierre de Solesmes. Graduale Triplex. Sablé sur Sarthe, 1979

· Anglés, Higinio. La música de las Cantigas del Rey Alfonso X el Sabio. ¿Madrid?, 1943.

· Aubry, Pierre. Estampies et danses royales. Les plus anciens textes de musiques intrumentale au Moyen Age. París, 1907

· Dronke, Peter. La lírica en el Edad Media. Ariel, 1995.

· Fernández de la Cuesta, Ismael. Les cantigas de amigo de Martin Codax. Cahiers de Civilisation Medievale 1982.

· Ferreira, Manuel Pedro. O som de Martin Codax. Casa de la moneda 1986, Lisboa.

· Mc Gee, Timothy. Medieval instrumental dances. Indiana University Press, 1989.

· Oviedo y Arce, Eladio. El genuino Martin Codax, trovador gallego del siglo XIII. Texto literario y musical. Boletín de la Real Academia Gallega. 1916-1917, nums. 109, 111, 112, 113, 114, 117.

· Reaney, George ed. The Manuscript London, British Museum, Additional 29987. A facsimile edition. American institute of Musicology, 1965.

· Tafall i Abad, Santiago. El genuino Martin Codax, juglar gallego del siglo XIII. Texto literario y musical. Boletín de la Real Academia Gallega. 1917. n° 118.

· Vindel, Pedro. Martin Codax. La siete canciones de amor: poema musical del siglo XII. 1915.

Instrumentos

Laureano Jesus Estepa García-Bravo

• Vihuela de arco. Copia de la iconografía de las Cantigas de Santa María.

Construida por Jesús Reolid, 1998. Mostoles, Madrid.

Carlos Zumajo Galdón

• Flauta travesera medieval.

Copia de diferentes miniaturas del s. XIII. Construida por Giovanni Tardino.

Frascati, Roma, 2001.

• Gaita. Sito Carracedo, Lugo, 1982.

Eduardo Moreno Vega

• Pandereta, pandero. Victor Barral, 2001

• Darbuca, crótalos, pandero con sonajas. Irán, 2004

Colaboraciones

Yurena Duque Zumajo, Sofia Alegre y Asuncion Tarrasó Alcalá:

Coro (Media Vita in morte summus, Chevalier mult estes guariz, Ben pode Santa María, Santa María Strela do día)

Eduardo Aguirre de Cárcer:

Darbuka (Chevalier molt estes guariz)

y pandero (Ben pode Santa María)

Grabación / Recording:

Conservatorio Superior de Música de Madrid.

Sala Manuel de Falla. 11 y 12 de Septiembre de 2004

Toma de sonido / Recording engineer:

José Miguel Martínez

Edición digital / Digital editing:

Pilar de la Vega

Producción / Production:

José Miguel Martínez, Pilar de la Vega

Comentarios / Texts:

Paco Peñarrubia, Elena Gómez y Carlos Zumajo

Traducción / Translation:

Gordon Burt, Elisabeth Fournier

Traducción textos poéticos / Translation of the poetic texts:

Textos franceses: Alain Durand

Textos restantes: Elena Gomez y Carlos Zumajo

Fotografía / Photograph:

Domingo Duque Rivero

Diseño gráfico / Design:

Pilar de la Vega

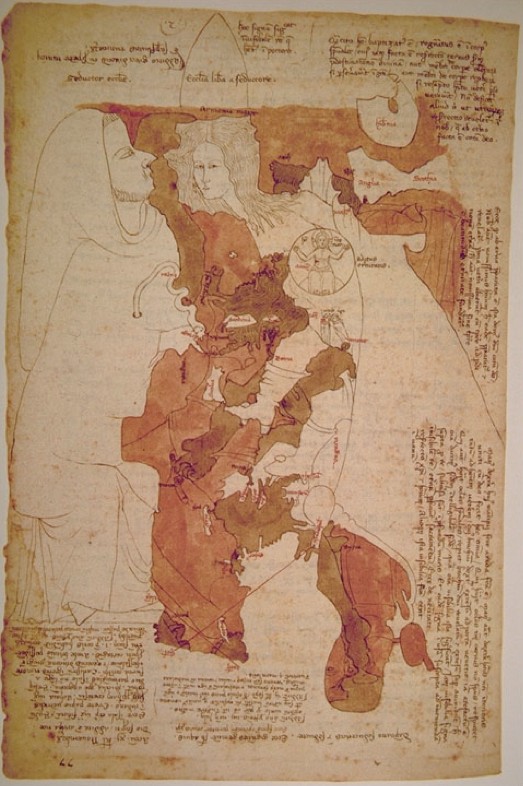

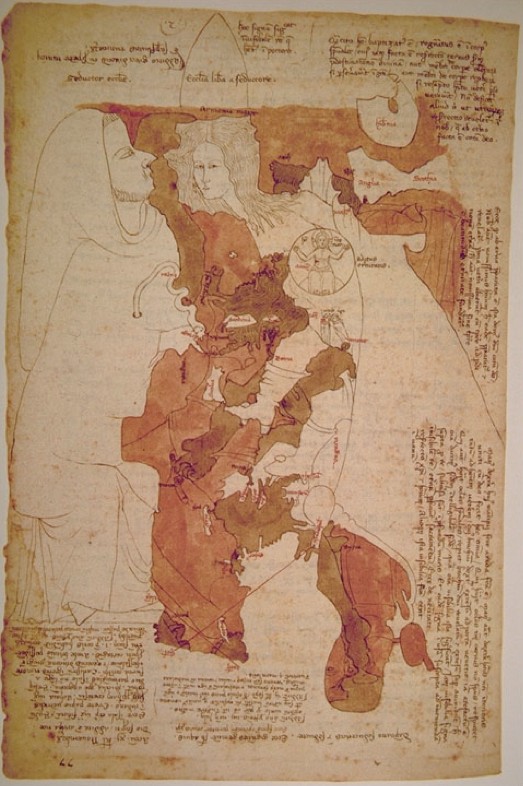

Portada / Cover:

Mapa de Europa y Africa del norte con rasgos humanos.

Opicinus de Canistris, s. XIV

Agradecimientos / Acknowledgements:

Rafael Marzo, José Carlos Gosálvez, Antonio Luengo, José Antonio Gonzalo, Alain Durand,

Paco Peñarrubia, Annie Chevreux, Jesús Diego, Paco Becerril, Laureano Cuevas

© & ℗ 2005 BANCO DE SONIDO