A Royal Songbook / Musica Antiqua of London

Spanish Music from the time of Columbus

medieval.org

Naxos 8.553325

1995

Cancionero Musical de Palacio

except Alonso Mudarra & Diego Ortiz

1. Calabaça [2:14]

2. Ay Santa María [2:42]

3. Pedro de ESCOBAR (c.1465-1535). Virgen bendita sin par

[3:36]

4. Juan de ANCHIETA (1462-1523). Con amores mi madre

[2:49]

5. GARCIMUÑÓS. Pues bien para esta [3:48]

6. Passamezzo [1:22]

7. Alonso MUDARRA (c.1510-1580). Pavana

d'Alexandre, Gallarda [2:30]

Tres Libros de Musica en Cifra para Vihuela

8. Tres morillas - FERNANDEZ. Tres moricas

[2:35]

9. GABRIEL. Aquella mora garrida [4:17]

10. Dentro en el vergel [1:15]

11. Johannes OCKEGHEM (c.1410-1497). De la momera [1:39]

(S'elle m'amera / Petite camusette)

12. Juan del ENCINA (1468-1530). Amor con fortuna [1:05]

13. Juan PONÇE (c.1480-1521). Como está sola mi vida

[2:21]

14. ROMÁN. O voy [2:06]

15. La Gamba [1:31]

16. Diego ORTIZ (c.1510-1570). Recercada

quarta [1:27]

Tratado de Glosas

17. LUCHAS. A la caça [1:52]

18. Alonso MUDARRA. Guárdame

las vacas [1:17]

Tres Libros de Musica en Cifra para Vihuela

19. Niña y viña [1:36]

20. Francisco de la TORRE. Danza alta [1:52]

21. Diego ORTIZ. Recercada tercera

[3:02]

Tratado de Glosas

Alonso MUDARRA

22. Si me llaman, a mí llaman [1:52]

23. Isabel, perdiste la tu faxa [1:16]

24. Fantasía que contrahaze la harpa en la manera de Luduvico

[2:22]

Tres Libros de Musica en Cifra para Vihuela

25. A la mia gran pena forte [2:46]

26. Dios te salve [3:04]

27. Ya somos del todo libres [2:22]

28. VILCHES. Ya cantan los gallos [4:33]

29. Dindirindín [1:38]

30. Juan del ENCINA. Cucú [1:14]

Geraldine McGreevy, soprano

Harvey Brough, tenor

Jacob Heringman, vihuela, lute, guitar

Musica Antiqua of London

Philip Thorby

Recording at St.

Martin's Church, East Woodhay, Hampshire

from 5th to 7th March 1995

Producer & Engineer: John Taylor

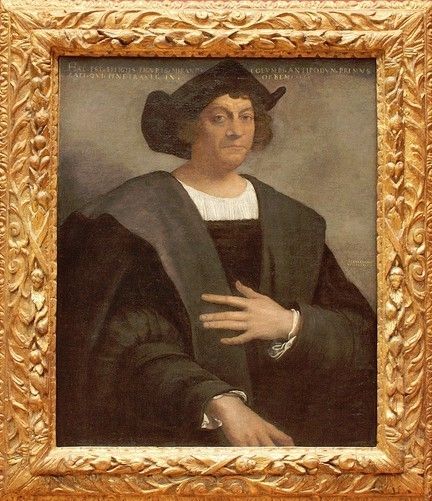

A ROYAL SONGBOOK

Spanish Music from the time of Columbus

Musical Sources

The marriage in 1469 of Ferdinand of Aragon to Isabella of Castile

brought the whole of the Spanish peninsula, with the exception of

Portugal, under direct rule from Madrid. With the end of the long wars

between Aragon and Castile came a flowering of Spanish nationalism,

religious fervour and culture. Nationalism resulted in 1492 in the

expulsion of the Moors from Spain, religious revival led to the

establishment of the Holy Inquisition; and one of the most vivid

illustrations of the flowering of the arts under the 'Catholic

Monarchs' is the Cancionero Musical de Palacio — the

Palace Song Book. A vast collection of songs composed between about

1440 and 1515, the manuscript was compiled at the Spanish court in

stages from 1500 to 1520. The practice of collecting an entire

repertoire, as an expression of pride in the music, and possibly a

desire to preserve it for posterity, dates from medieval times.

The Song Book is the source for most of the music in the

present recording, but two later printed collections have also been

consulted. Tres Libros de Musica en Cifra para Vihuela by

Alonso Mudarra (Seville, 1546) contains not just music intabulated for

the vihuela, but also solos for the guitar, and vihuela-songs. Mudarra,

a liberal-minded canon at Seville Cathedral is arguably the most

musically rewarding of the vihuelistas, and all the vihuela, lute and

guitar music on this recording is by him.

The other publication from which we have taken music is Tratado de

Glosas by Diego Ortiz (Rome 1553). A treatise on the art of

improvising music either unaccompanied or based on existing songs or

dances, the Tratado is written in terms of the viol, on which

Ortiz was a famous virtuoso. At the end of the book Ortiz gives

examples of most of the types of improvisation, thus leaving some of

the earliest surviving solo music for the viol.

These two publications, while produced later than the Palace Song

Book, are particularly relevant to any programme of Spanish

renaissance music, because of the instruments for which they are

written. The vihuela is essentially a guitar-shaped lute,

unique to sixteenth-century Spain, while the little renaissance guitar

was eventually to grow into that country's national instrument. The

viol surely the most important ensemble instrument of the Renaissance,

seems to have been born in Spain (sharing its parentage with the

vihuela), travelling later to Italy and Northern Europe.

Perhaps the most striking feature of the Palace Song Book is

the sheer variety displayed in its 463 pieces. The earliest songs are

in the medieval courtly love tradition: but late texts range from the

earthiest sexual innuendo, through artfully simple pseudo-folk-songs,

to sacred songs of passionate devotion.

Our recording reflects this range. The crude phallic symbolism of Calabaça

[1], with its ironic (even sacrilegious) reference to the Virgin Mary,

is followed directly by two pieces inspired by fervent Marian texts [2

and 3]. Ay Santa Maria first occurs in the earlier Colombina

manuscript in a version which lacks the haunting simplicity of this Palace

Song Book version. Whilst in Virgen bendita sin par Escobar

makes use of a melody which appears elsewhere in the Song Book with a

simple pastoral text. The melody is here transformed both by the text

and by Escobar's subtle harmonies into an extended sacred dance-song of

luminous beauty.

Love Songs

As one might expect, most of the songs in the Palace Song Book

are love-songs: but here again there is variety. A number of texts take

the form of a daughter confiding to her mother about her lover, a genre

peculiar to this repertoire. In Con amores [4], for example,

the girl recounts (in a suitably sleepy quintuple metre) her dream of

love; by contrast Pues bien para ésta begins in the

middle of a heated argument between the daughter, who is desperate to

marry, and her mother, who wants her to wait. (The daughter, by an

outrageous combination of threats and emotional blackmail, gets her

way.)

Another type of Spanish love-song deals with the Moorish lover, male or

female. In the delightful miniature Tres Morillas [8] the poet

is haunted by the memory of Axa, Fatima and Marien, three Moorish girls

in Jaen. Aquella mora garrida is a more complex poetical

conceit: the text is sung by a girl who has been carried off by Moors,

but the refrain is a folk-song sung by a man ("That lovely Moorish

girl, her love brings pain to my life"). Both poet and composer handle

this double perspective with great skill.

A more conventional vein of love-song is Como está [13]

in which the singer laments the departure of her lover.

Pastoral Texts

One strand in the Palace Song Book which is parallelled in other

contemporary collections is the pseudo-rustic element. In England Henry

VIII and his court played at hunters and foresters in May-Day

festivities; in France and Italy too there is a substantial pastoral

repertoire. So it comes as no surprise to find pieces such as A la

caça [17], a glorious evocation of the hunt of love, or Niña

y Viña [19], where a country girl recounts (to her mother!)

how she was seduced by a vineyard keeper. The instrumental Guárdame

las vacas [18] is a setting for solo guitar of a song supposedly

sung by a seductive cow-girl. Rural imagery crops up throughout the

repertoire, from pumpkins [1] to birds [28, 29, 30].

Problem Texts

Throughout the vocal repertoire of the early renaissance there occur

songs whose texts are short and enigmatic. In such pieces it is not

always possible to tell whether what survives is a single strophe from

a longer work, or whether today we simply miss references and

resonances which would have fleshed out the texts for a contemporary

listener. Spanish collections include many works of this type: the

apparently inconsequential words of the vihuela-songs Isabel

and Si me llaman [22, 23] are at odds with the contrapuntal

elegance of Mudarra's music, but the very quality of the vihuelist's

elaborate settings serves to colour in the sketchy images of the verse.

Instrumental Performance

One way to avoid the problems posed by an apparently incomplete text is

to perform such a work instrumentally. Vocal music formed the core of

instrumental repertoire in the Renaissance, performed with no

ornamentation (for example Amor con fortuna [12]), with

decoration shared between the parts (for example Dentro en el vergel

[10] and De la momera [11]) or with one voice used as a vehicle

for elaborate improvised divisions in the manner described by Diego

Ortiz (for example Dios te salve [26]).

Instrumental virtuosi borrowed not only songs but also dances as a

basis for their repertoire: the galliard La gamba [15] and the

saltarello Alta [20] were both taken as the starting-point for

imaginative divisions by Diego Ortiz [16 & 21]. In the case of the Passamezzo

[6] it is Alonso Mudarra who transforms the simple chord sequence into

the graceful Pavana d'Alexandre for solo guitar [7].

Indeed composers such as Mudarra gave us some of the earliest music for

specified instruments. The tablature in which the lute, vihuela and

guitar repertoire was written largely defines the instrument for which

it was intended. The most substantial such piece on this recording [24]

is a homage to the blind harp virtuoso Luduvico: the Fantasia 'in the

manner of Luduvico' paints an exhilarating picture of an improvising

virtuoso. Much of the colour is given by notes which, explains Mudarra,

will at first sound like false notes, but which must be played with

conviction.

Sacred and Profane

Our recording ends as it began, with two groups of contrasted pieces. A

la mía [25] and Ya somos del todo libres [27] set

texts dealing with the Crucifixion; the first in the voice of Christ

foretelling his fate (with its refrain "they will divide my clothes and

cast lots for them"), the second celebrating man's release from death

"and from the power of accursed Lucifer". Between these pieces is De La

Torre's hymn to the Cross Dios te Salve [26], here

instrumentally performed.

The final group, by contrast, returns to the world of rustic imagery,

with three songs about birds. In Ya cantan los gallos [28] the

crowing of the cock awakens a pair of young lovers, she afraid of

scandal should they be discovered, he prepared to risk anything for

love. There is a sting in the tail of Dindirin [29], though it

begins innocently enough: a girl meets a nightingale, and prettily asks

it to take a message to her lover — but the message is that she

has got married. And with Cucú [30] we return to the

earthy mood of Calabaça [1]: a

tongue—in—cheek evocation of the song of the cuckoo

repeatedly gives way to a reminder of its less welcome significance as

the unwelcome symbol of the cuckold!

© 1995 Philip Thorby