medieval.org

L'Oiseau Lyre 433 148

1991

2007: L'Oiseau Lyre 475 9103

medieval.org

L'Oiseau Lyre 433 148

1991

2007: L'Oiseau Lyre 475 9103

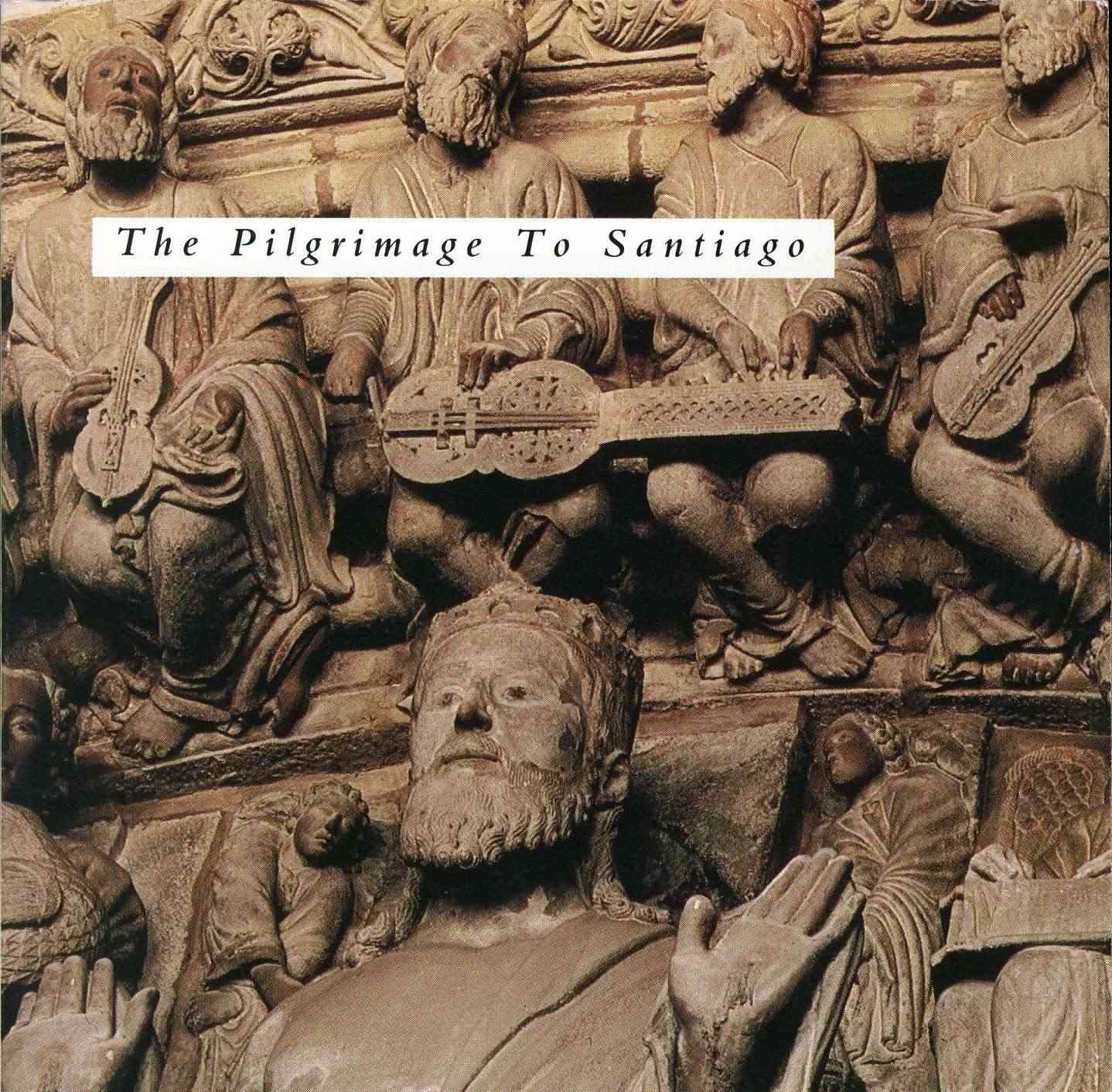

Et in circuitu sedo sedilia

vigintiquattuor, et super thronos vigintiquattuor seniores sedentes

circumamicti vestimentis albis, et in capitibus eorum coronae aureae...

These ‘citharas’ were interpreted

very freely by the medieval artists and sculptors, but normally they

were shown as stringed instruments. The twenty-four Elders so

brilliantly sculpted by Mateo on the great Pórtico de la Gloria

of Santiago Cathedral play fiddles, gittems, harps, rottas, psalteries,

knee fiddles and, in the centre of the semi-circular ensemble, an

organistrum or two-man hurdy-gurdy.

Nimio

gaudio miratur, qui peregrinantum choros circa beati Jacobi altare

venerandum vigilantes videt: Theutonici enim in alia parte, Francia in

alia, Italia in alia catervatim commorantur, cercos ardentes manibus

tenentes; unde tota ecclesia ut sol vel dies clarissima illuminantur.

Alii citharis psallant, alii liris, alii timphanis, alii tibiis, alii

fistulis, alii tubis, alii sambrecis, alii violis, alii rotis

Britannicis eel Gallicis, alii psalteriis, all diversisi generibus

musicorum cantanda vigilant, alii pecuntur diversa genera linguarum,

diversi clamores barbarorum loquele et cantilene Theutonicorum,

Anglorum, Grecorum, ceterarumque tribuum et gentium diversarum omnium

mundi climatum.

In this wonderful description of the pilgrims

singing and playing around the altar of Santiago Cathedral during the

feast day vigil of St James, the list of instruments played together by a

large group of international participants includes harps, lyres, drums,

shawms, flutes, trumpets, fiddles, British or French rotes and

psalteries. Such spontaneous music-making must have been informal, but,

assuming a common repertoire, reasonably successful and impressive!

CD 1

NAVARRE AND CASTILE

1. Quen a Virgen ben servira [8:23]

Escorial MS CSM 103

soprano CB, chorus, lute TF, fiddle PB, tbilat SH

2. Belial vocatur ~ TENOR [2:10]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 81

sopranos TB CB, alto KSz, bells SH, organ DR

3. Surrexit de tumulo [1:36]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 91

sopranos TB CB, bells SH, organ DR

4. Non e gran cousa [9:54]

Escorial MS CSM 26

soprano CB, chorus, lutes TF PCh, harp HD, fiddles PB GL PS CM MC ML SP SG RB, tabors SH, tambourine FR

[+ instrumental CSM 77 ]

5. Ex illustri [2:03]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 132

sopranos TB CB, alto KSz

6. Alpha bovi ~ DOMINO [1:53]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 83

sopranos TB CB, bells SH, organ DR

7. 4 Planctus [14:27]

soprano CB, symphony PhP, gittern TF, fiddle PB

· Plange Castella misera [2:44]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 172

· instrumental interlude [2:59]

· Quis dabis capiti meo aquam [2:25]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 170

· Rex obiit et labitur [2:45]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 169

· O monialis concio [3:34]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 171

8. Verbum bonum et suave [3:41

Las Huelgas MS Hu 54

sopranos CB TB, mezzo CK, alto KSz, bells SH, organ DR

9. Agnus Dei ~ Regula moris [3:05]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 24

sopranos CB TB, mezzo CK, bells SH

10. Fa fa mi fa ~ Ut re mi ut [1:01]

Las Huelgas MS Hu 177

sopranos CB TB

11. Dum pater familias [5:29]

Codex Calixtinus cc 117

gitterns TF PCh, harps HD RH, zither AC, psaltery PhP, fiddles PB GL PS CM MC ML SP SG RB, organistrum MR-WL, tabors SH, tambourine FR

CD 2

LEÓN AND GALICIA

1. De grad'a Santa Maria [17:31]

Escorial MS CSM 253

soprano CB, chorus, lute TF, harp HD, fiddles PB GL PS CM MC ML SP SG RB, symphony PhP, recorder WL, nakers · tabors SH, tambourine FR

2. Annua gaudia [3:13]

Codex Calixtinus cc 99

tenor JMA, baritone SCh

3. Ben com'aos que van per mar [7:49]

Escorial MS CSM 49

soprano CB, chorus, lute TF, fiddle PB, recorder PhP, nakers SH

4. Regi perennis glorie [4:41]

Codex Calixtinus cc 101

tenor JMA, baritones MG SCh, organ DR

5. [5:51]

· Non sofre Santa Maria

Escorial MS CSM 159

· Por dereito ten a Virgen

Escorial MS CSM 175

fiddles PB GL CM MC ML SP SG RB, tabors SH FR

6. Nostra phalanx [3:22]

Codex Calixtinus cc 95

baritone MG, bass SG

7. A Madre de Deus [6:50]

Escorial MS CSM 184

soprano CB, chorus, lute TF, fiddle PB, recorder PhP, tbilat SH

8. Congaudeant catholici [4:50]

Codex Calixtinus cc 96

baritones MG SCh, bass SG

9. MARTIN CODAX. 7 Cantigas de amigo [12:31]

soprano CB, chorus, gittern, symphony PhP, fiddle PB

· Ondas do mar de Vigo [2:15]

ca I

· Mandad' ei comigo [1:34]

ca II

· Mia yrmana fremosa [2:40]

ca III

· Ay Deus se sab' ora [2:20]

ca IV

· Quantas sabedes amar amigo [1:12]

ca V

· Eno sagrado en Vigo [1:03]

ca VI

· Ay ondas que eu vin veer [1:27]

ca VII

10. Dum pater familias [5:48]

Codex Calixtinus cc 117

chorus, gitterns TF PCh, harps HD RH, zither AC, psaltery PhP, fiddles PB GL PS CM MC ML SP SG RB, organistrum MR-WL, tabors SH, tambourine FR

NEW LONDON CONSORT

Philip Pickett

Catherine Bott, soprano

Tessa Bonner, Olive Simpson, Jaqueline Barron, Julia Gooding, Ana-Maria Rincón — sopranos

Jenevora Williams, Catherine King — mezzo-sopranos

Kristine Szulic — alto

John Mark Ainsley — tenor

Michael George, Stephen Charlesworth, Robert Evans — baritones

Simon Grant — bass

Tom Finucane, Paula Chateauneuf — lute, gittern

Hannelore Devaere, Rachel Hamilton — harp

Philip Pickett — psaltery, symphony, recorder, tambourine

Andres Cronshaw — zither

Pavlo Beznosiuk, Giles Lewin, Peter Syrus, Carla Mastandreas, Mairi Campbell — 5-String fiddles

Mark Levy, Susanna Pell, Sarah Groser, Richard Boothby, Mairi Campbell — 3-String ‘8-Shape’ fiddles

Mary Remnant — organistrum

William Lyons — organistrum, recorder

David Roblou — organ

Stephen Henderson — bells, nakers, tbilat (Moroccan clay drums), tabor

Frank Ricotti — tabor, tambourine

Chorus

Catherine Bott · Tessa Bonner · Olive Simpson

Jaqueline Barron · Julia Gooding · Ana-Maria Rincón

Jenevora Williams · Catherine King · Kristine Szulic

John Mark Ainsley · Michael George, Stephen Charlesworth

Robert Evans · Simon Grant

Producer: PETER WADLAND

Engineer: JONATHAN STOKES

Tape editor: TIMOTHY BULL

This recording was made using B & W Loudspeakers

Recording location: Temple Church, London,

31 October - 4 November 1989

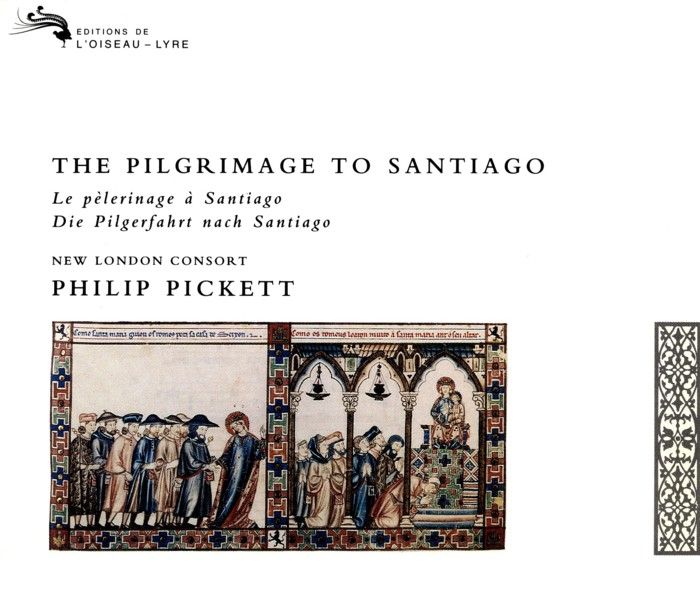

Cover:

Illustration from the Cantigas de Santa Maria manuscript

in the library of the Monasterio de San Lorenzo de el Escorial.

(Photo

released and authorized for use by the Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid)

Booklet cover:

Detail from the tympanum of the Portico de la Gloria

of the Cathedral in Santiago de Compostela.

Photo: Arxiu Mas

Art direction: Ann Bradbeer

SOURCES

El Escorial, Real Monasterio de El Escorial b.I.2

El Escorial, Real Monasterio de El Escorial T.j.I

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional 10069

Burgos, Codex de Las Huelgas

Santiago, Biblioteca de la Catedral, Codex Calixtinus

Las Siete Canciones de Amor, ed. Vindel Madrid 1915 (Facsimile)

EDITIONS AND PERFORMING VERSIONS BY PHILIP PICKETT

℗ © 1991 The Decca Record Company Limited, London

NEW LONDON CONSORT

directed by Philip Pickett

Lute

Tom Finucane - Syrian, Damascus 1973

Paula Chateauneuf - Saleem, Damascus 1896

Gittern

Tom Finucane - Barber, London 1982

Paula Chateauneuf - NRI, Manchester 1977

Harp

Hannelore Devaere - Hobrough, Beauly 1987

Rachel Hamilton - Hobrough, Beauly 1986

Psaltery

Philip Pickett - Booth, Wells 1981

Zither

Andrew Cronshaw - Hopf, Wiesbaden 1935

5-String Fiddle

Pavlo Beznosiuk - Shann, Caemarfon 1978 | Gotschy, Wain 1983

Giles Lewin - Shann, Caernarfon 1983

Peter Syrus - King, Guildford 1973

Carla Mastandreas - Ellis, Hereford 1980

Mairi Campbell - Hansford, London 1979

3-String “8-Shape” Fiddle

Mark Levy - Davies, London 1979

Susanna Pell - Bridgewood, London 1989

Sarah Groser - Crumpler, Leominster 1985

Richard Boothby - Crumpler, Leominster 1983

Symphony

Philip Pickett - Ellis, Hereford 1977 | Palmer, London 1981

Organistrum

Mary Remnant/William Lyons - Crumpler, Leominster 1980

Recorder

Philip Pickett - Von Huene, Boston 1984

William Lyons - Moeck, Celle 1984

Organ

David Roblou - Sillman, London 1984

Bells

Stephen Henderson - Whitechapel Bell Foundry, London 1985

Nakers

Stephen Henderson - Williamson, Spalding 1975

Tbilat

Stephen Henderson - Moroccan, Marrakesh 1982

Tabor

Stephen Henderson - Williamson, Spalding 1975 | Stevenson, London 1985

Frank Ricotti - Williamson, Spalding 1975 | Stevenson, London 1985

Tambourine

Philip Pickett - Williamson, Spalding 1975

Frank Ricotti - Williamson, Spalding 1975

Organ prepared and tuned by Malcolm Greenhalgh

THE PILGRIMAGE TO SANTIAGO

Philip Pickett

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

This

is not the first recording of medieval music associated with the

pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, and it will probably not be the

last.

In particular, this project owes a great debt to Thomas Binkley

and Andrea von Ramm, whose recordings of this repertory had a profound

influence on the early development of the New London Consort; and to

Carlos Villanueva, director of the Grupo de Camara at the

University of Santiago de Compostela, who unlocked many doors for us and

made our visits to Santiago de Compostela not only more profitable, but

also more stimulating and enjoyable.

I would also like to express my

personal gratitude to the librarians at El Escorial and Santiago

Cathedral for allowing me considerable access to the precious

manuscripts in their care.

There are, of course, only a few songs

which actually deal with Santiago, the pilgrims and the pilgrimage, and

these appear on all the recordings. They are recorded here complete and

uncut for the first time. This recording also introduces new sounds and

new scholarship, and delves more deeply into the polyphonic repertories

of the Las Huelgas manuscript and the Codex Calixtinus.

THE CULT OF SAINT JAMES

Europe

houses many shrines built in medieval times at the burial sites of

saints or apostles, or at places associated with miracles performed by

the Virgin Mary. In Spain, one such shrine was especially famous in the

middle ages — Santiago de Compostela, in the north-west, where pilgrims

came from all over Europe to worship at the grave of St James.

The

first Apostle to be martyred, James the Elder, brother of John and son

of Zebedee, was possibly beheaded in Jerusalem by Herod Agrippa I in 44

AD. James was born in Jaffa. His mother, Mary Salome, was the sister of

Mary, mother of Jesus, thus connecting him directly with the Holy

Family. It has been claimed that before his death James preached in

Spain, but St Paul, in his Epistle to the Romans 15: 20-24, suggests

that Christ was not known in the peninsula.

One source claims

that the relics of St James were found in 813 in Padrón by the hermit

Pelayo with the aid of a miraculous light, another that they were

discovered in Lebredón in 847. The most common belief was that James had

preached in Spain, following Christ's commission to preach the Gospel

to the ends of the earth, and then returned to Jerusalem. After his

martyrdom two disciples brought his body from Jerusalem to Padrón, where

a shrine and succession of churches were built over the tomb. Whatever

the truth of the story, the final resting place of the relics was called

Santiago de Compostela — St James in the Field of Stars, surely a

reference to Pelayo's miraculous light — and became one of the three

main centres of Christian pilgrimage.

Alfonso VI, Imperator Totius Hispaniae,

provided the necessary funds for the building of a Cathedral dedicated

to St James, as well as for the repair and maintenance of the principal

pilgrim road — the Camino Francés. Work was begun on the Basilica in 1078 and completed in 1122. The famous Pórtico de la Gloria, the west door and façade, was added between 1166-88. The workmen who built the Cathedral were supervised by Frenchmen.

By

the 12th century four main pilgrimage routes crossed France, following

Roman roads, and these met at Puente la Reina. The journey from there to

Santiago along the Camino Francés took at least eight days, and

the pilgrims could stay at hospices, often monastic, some twenty miles

apart along the way. They were entitled to free lodging and food, and

were protected by civil law. Many adventures took place along the road,

some of them requiring the help of the Virgin Mary. These are recorded

in the Cantigas de Santa Maria, assembled between 1250-80 by Alfonso el Sabio, King of Castile and León. But not all the music of the Camino Francés

tells of the miracles of the Virgin — there are also Latin conductus

and motets, marching songs, love songs and laments. All the pieces on

this recording tell of the pilgrims and their adventures, or come from

the most important resting places along the way.

THE PILGRIM ROAD

NAVARRE

The

monastery of San Salvador de Leyre can be found just to the north of

the pilgrim road that runs between Jaca and Puente la Reina. The Cantiga

Quen a Virgen ben servira tells how the 10th century abbot, San

Virila, spent 300 years listening to the song of a bird. This abbot was

born in Tiermas and is known to have lived for some time at the

monastery of Samos near Triacastela. He was buried in Leyre, but his

remains were later moved to Pamplona cathedral.

CASTILE

For

travellers along the pilgrim road, Burgos was the most important resting

place, with many hostels and favourable laws governing matters of

special interest to them. The Codex de las Huelgas was compiled at the Cistercian Convent there.

The 13th century cleric and poet Gonzalo de Berceo probably wrote his 25 Milagros de Nuestra Señora

at the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla for the people of La

Rioja. They form the greatest Castilian contribution to Marian

literature, and among them is the story of the pilgrim who sinned

carnally and met the Devil on the road to Santiago — the story also told

in the Cantiga Non e gran causa. Perhaps

for Berceo it was a local miracle.

LEÓN

The miracle described in the Cantiga De grad'a Santa Maria

occurred before the altar of the church of Santa María la Blanca in

Villalcázar de Sirga, once known as Santa Maria de Villasirga or simply

Villasirga. This 12th century church contains the sepulchre of Don

Felipe, brother of Alfonso el Sabio — an important connection between

the Virgin and Alfonso's Cantigas de Santa Maria.

Between Villálcazar de Sirga

and León is the town of Sahagún. To the south lies the church of the

Franciscan monastery La Peregrina, where the Pilgrim Virgin is

venerated. The Cantiga Ben com'aos tells how she changed her staff into a ray of light to guide a band of pilgrims by night.

GALICIA

It is impossible to pinpoint the exact location of the miracle described in the Cantiga A Madre de Deus, but the text tells us that it occurred in the mountains near to Santiago.

The library of the great Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela today holds the famous Codex Calixtinus,

the provenance and content of which seem to have been widely

misunderstood for centuries. The manuscript contains a guide to the

pilgrim road as well as music associated with St James and the

pilgrimage.

The seven Cantigas de Amigo of Martin Codax tell

of a girl who sits on a hill overlooking the bay of Vigo. Although Vigo

does not lie on the pilgrim road, it is only a little way from Padrón,

where the body of St James is believed to have arrived in Spain.

CANTIGAS DE SANTA MARIA

Monophonic

song in Spain must be regarded as a direct outgrowth of the troubadour

movement. From the time of William IX of Aquitaine contact between the

ruling families of southern France and the Christian kings of Spain was

frequent and close. The large retinues that accompanied these rulers on

their many visits to each other naturally included troubadours and

jongleurs, who also travelled widely on their own. French troubadours

found a ready welcome at Spanish courts and Provençal became the

language of poetry south of the Pyrenees until, in the 13th century,

Spanish songs in the vernacular began to appear. Thus the Cantigas de

Santa Maria originated in a cultured and aristocratic society which

included troubadour song among its many amusements.

Alfonso el Sabio

(the Wise, 1221-84), king of Castile and León from 1252 until his

death, was an enthusiastic patron of the arts and sciences and

established an enduring cultural foundation for the future of his

kingdom. He seems to have been particularly fond of poetry and music,

and his court was not only a haven for French, Islamic and Jewish

culture, but also a natural refuge for troubadours fleeing from the

Albigensian Crusade against the Cathar heresy in Provence.

In literature Alfonso regarded the Cantigas de Santa Maria

as his finest achievement. Assembled between 1250 and 1280, this is a

large collection of over 400 songs telling in a new way the traditional

Marian miracles inherited from late classical Germanic and Romanic

medieval Latin sources.

No New Testament figure owes more to

legend than that of the Virgin Mary. The Gospel account in which she

rarely appears and still more rarely speaks must have seemed

increasingly inadequate and so there arose in primitive times the

apocryphal stories which later satisfied the medieval appetite for

information about her.

In Christian theology the cult of Mary

began to grow in the 6th and 7th centuries. It made some headway in the

circle around Charlemagne's court, and various Offices and Feasts were

introduced into the Liturgy during the 9th and 10th centuries, but the

worship of the Virgin remained little more than a variant of the cults

of the individual saints, holding no special significance until early in

the 11th century, when the popular Marian legends began to be written

down. These were further assembled into collections in several countries

during the 12th century, each collection being given a title such as

‘Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary’. From then on the cult developed

quickly — the Office of the Virgin was recited daily, the greatest

cathedrals were built in her name, the dogma of the Immaculate

Conception was anticipated and the new Orders, the Franciscans and

Dominicans, spread her cult among the people.

The poems collected

by Alfonso were all written in Galician — considered by Spanish poets

from the 13th to the 15th centuries as the most suitable language for

lyric poetry, and probably chosen by Alfonso not only because the Cancioneros

of the Galician minstrels had already proved that Galician was best for

the creation of a universally understood lyric epic, but also to link

his collection with the vernacular repertory associated with Santiago de

Compostela.

The texts of the Cantigas are extremely vivid

and down-to-earth. Alfonso makes use of local oral traditions, and

even, he claims, of his own experience — often distinguishing wonders

read about from those heard and seen. The Cantigas recount household

tales and widespread legends, honour foreign shrines, tell of pilgrims

journeying to Spain, and refer to England, France, Italy and other

countries. In every case the Virgin appears at a crucial moment to

dispense mercy and justice. Delight and belief in the miracles may have

been genuine enough, but the detailed accounts of Boccaccio-like

situations that call for Mary's intervention suggest that audiences and

performers alike enjoyed the sins at least as much as the salvation.

It may be a coincidence that some of the stories are set in Soissons, home of Gautier de Coincy, but Gautier's Miracles de Nostre Dame had certainly established a recent literary and musical precedent for the Cantigas

and the idea of the collection as a whole must surely have owed a debt

to Gautier. Even the structure of the Cantigas is reminiscent of

Gautier's epic.

Gautier's Miracles de Nostre Dame form a

massive verse narrative of some 30,000 lines recounting the miracles

associated with the Virgin. He explains that he found these stories in a

Latin manuscript. Several such sources survive, but it is impossible to

trace the origins of all the material contained in his work. The Miracles

was written between 1214 and 1233 while Gautier was Prior at

Vic-sur-Aisne, and survives in more than 80 manuscripts. Gautier

incorporated a number of songs with music into his long narrative, and

22 of the surviving sources include melodies for them. These songs

appear at various points in the text and are mostly new poems in praise

of the Virgin set to pre-existing melodies from a variety of sources,

including monophonic and polyphonic works associated with the repertory

of Notre Dame in Paris. They constitute the earliest substantial

collection of sacred (and above all, Marian) songs in the vernacular. In

contrast, other trouvères produced an almost exclusively secular

repertory.

Alfonso's Cantigas de Santa Maria have survived

in four lavish manuscripts. Three contain the same poems and melodies,

with a few exceptions and minor variants; the fourth contains only poems

— staves had been drawn in preparation but the melodies had never been

added. Every tenth poem in the collection is a song in praise of the

Virgin (Cantiga de Loor). The regularity of this arrangement — so

reminiscent of Gautier's plan — is broken only at the beginning of the

collection, where a sung Prologo precedes the first Cantiga de Loor, and at the end where a Petiçon

follows the last. In the manuscripts the songs are carefully numbered;

rubrics identify the subject of each, strip-cartoon-like series of

beautiful illuminated miniatures tell the story of each miracle, and

miniatures depicting musicians playing or tuning a wide variety of

instruments accompany each of the Cantigas de Loor. These

pictures differ in the various manuscripts, with the exception of those

depicting Alfonso himself, all of which concur in showing him as

supervisor of, or instructor to, clerical and secular scribes who are

compiling the Cantigas while minstrels tune up or wait. Taken

together, the miniatures supply exceptionally accurate and indispensable

information about the instruments in use at Alfonso's court — more than

forty different kinds in all! Interestingly, Moors, Jews and women are

shown playing them as well as aristocratic and rustic Hispanic figures.

There

is some disagreement as to whether Alfonso merely supervised, or wrote

some of the words and music himself. The manuscripts state several times

that he ‘made’ certain Cantigas, and in some he speaks in the first

person. On the other hand, in his General Estoria he explains

that ‘the King writes a book...in the sense that he gathers the material

for it.. adapts it, shows the manner in which it is to be presented and

orders what is to be written’. Whatever the truth of the matter,

Alfonso and his team certainly borrowed a number of well-known songs of

the day for the Cantigas melodies, and evidence shows that these

were mainly drawn from French-based sources on both sides of the

Pyrenees. Of the tunes so far identified, some are trouvère songs, some

come from the Notre Dame repertory, some recall songs of the troubadours

and some are even reminiscent of the few extant notated dance tunes.

CODEX DE LAS HUELGAS

Las

Huelgas, a Cistercian convent near Burgos in Old Castile, was founded

by Alfonso VIII, famous for his victory over the Moslems at the battle

of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212. The Codex de Las Huelgas was

compiled for the convent around 1300, and has remained there. It is

especially important as the first major source to be wholly notated in

mature Franconian notation, the unambiguous nature of which can be

remarkably helpful in parallel transcriptions and analogous

interpretations of the remainder of the (more ambiguously notated)

repertory.

Most of the music dates from the late 13th century,

but there are some earlier pieces and some early 14th century additions.

A large number of pieces derive from the repertory of Notre Dame, and

some exist elsewhere in other versions with different texts: Surrexit de tumulo is a contrafactum of Exiit diluculo (Carmina Burana I); Verbum Bonum is the original of the parody Vinum Bonum (Feast of Fools); and the 3-part conductus motet Alpha bovi

also exists as a three-part clausula, a two-part motet and a monophonic

song by Gautier de Coincy. Interestingly enough the tenor is not quite

the Domino tenor. It seems to have been altered in a few places

to fit the melody, suggesting that the melody was a pre-existing folk

tune and someone realised that the notes of the Benedicamus Domino tenor could almost be fitted to it!

Several

polyphonic works are known only through this source and are possibly

Spanish in origin, though they display clearly the close connection

between the peninsula and France — examples here are Belial vocatur, an unusual 4-part motet; Ex illustri,

a rare duple-metre motet honouring St Catherine; and Fa fa mi fa. It

has also been suggested that many of the texts are in fact products of

Spain. They are often unique to this source, or have concordances only

in other Spanish manuscripts, so it would seem that a school of Spanish

poets flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries who were well aware of

the subject matter and techniques employed by their contemporaries in

France.

The Codex contains 45 monophonic and 141 polyphonic pieces covering a wide range of styles — motet; conductus (Surrexit de tumulo); sequence (Verbum bonum et suavi); conductus motet (Belial vocatur/Tenor, Ex illustri, Alpha bovi/Domino); a solmization exercise (Fa fa mi fa/Ut re mi ut); trope (Agnus Dei/Regula moris); Sanctus setting; gradual; alleluia; and four unique planctus or laments. The first of these, Plange Castella,

was written on the death of Sancho III, father of the convent's founder

Alfonso VIII. When Sancho died the kingdoms of Castile and León were

divided between two sons. Rex obiit, the third lament, was written to honour Alfonso VIII himself, and Quis dabit capiti meo acquam was perhaps written for his grandson Ferdinand, later to be canonised. The last planctus,

O monialis concio, laments the death of an Abbess of Las Huelgas — the rubric reads De dompna Maria Gundissalvi de Aguero, abtissa et nobilissima super omnes abbatissas.

CODEX CALIXTINUS

Known to all as either the Codex Calixtinus or the Liber Sancti Jacobi, this source, now held in the library of Santiago Cathedral, is described by its author simply as Jacobus.

The contents of Jacobus

include, in five books, a letter fictitiously attributed to Pope

Calixtus II, the supposed editor of the manuscript; the story of

Charlemagne's peers attributed to an Archbishop Turpin of Rheims; 22

miracles of St James; the Legend of St James; what can only be described

as a 12th century guidebook for pilgrims on the road to Santiago; and

finally, in Books I and V, incipits and music for the Office and Mass,

monophonic and polyphonic conductus and versus — a large number

of chants and polyphonic settings which have long been regarded as a

selection from the early musical repertory of the Cathedral of Santiago

de Compostela.

But it is now widely accepted that the manuscript

was in fact an all-purpose teaching manual belonging to an itinerant

French grammar and music master and his usher, which also embodied the

contributions of a succession of such masters.

The script,

decoration and text of the main body of the work is French, though some

have argued that the musical notation is Spanish. It was probably copied

at or near Vezelay, and one Aimeric Picaud (thought to be the

schoolmaster's usher) was probably the composer of some of the

polyphony. The other pieces are all attributed in the manuscript either

to unknown composers or to composers associated with Paris and Notre

Dame — Magister Airardus Viziliacensis, Magister Gauterius, Ato Episcopus Trecensis and Magister Albertus Parisiensis are the names attached to the four conductus recorded here.

In

fact, it seems that the history of the contents of Jacobus may have

begun at St Jacques de la Boucherie, Paris. The master is thought to

have taught at a school connected with St Jacques, then gone to Cluny,

where apparently not all his work was approved by the monks.

The

manuscript, already quite unusual in its scope, is full of deliberate

and learned distortions of grammar, rhetoric, theology and logic, all to

be spotted and corrected by students; and on closer examination it

seems that the services contained in Book I are for secular, not

monastic, Offices; the presence of an abnormal number of Benedicamus settings (for use at the end of lessons?) would support the idea of use in school.

Whatever

is intentionally wrong with any of the items ascribed to Calixtus

himself, there is nothing wrong with the music, though theories that it

was meant specifically for use at Santiago cathedral are not tenable.

Most of it would be suitable for school music teaching and worship, and

some of the service music of Book I seems to belong to a kind of

altemative Feast of Fools, celebrated by the master and his students

either at Second Vespers on 30 December, the Feast of the Translation of

St James, or on 25 July, the Feast of the Passion of St James.

Even

the Pilgrim Guide was designed for teaching, filled as it is with bad

Latin, quotations to be spotted, geography lessons and schoolboy

howlers; and the guide covers the same ground again and again, each time

the journey having a different secondary theme. At least the guide

appears to be written from firsthand experience. Whoever wrote it

probably visited Santiago on business rather than as a pilgrim around

1130, possibly in connection with the administration of a grammar school

in Santiago.

The original material for Jacobus was

probably collated by 1140, and though many later copies have been

identified — all more or less incomplete — it would seem that the

manuscript held in Santiago Cathedral is the archetypal fair copy.

Appended

to the Codex are several leaves, almost certainly Spanish in origin.

One of the last, possibly older than the rest, contains the Latin

pilgrim song Dum pater familias. It was probably well-known and,

like the French material, seems to have had some didactic intent — St

James's name appears in several cases of the first declension: Jacobus, Jacobi, Jacobo.

It seems that most of the Codex,

including the polyphony, was present in Santiago by 1173, when Arnaldus

de Monte, a monk of Ripoll, made a copy of it. He says that he found it

‘In Ecclesia’ — which, given all the Spanish additions, probably

meant that the volume was in possession of a schoolmaster at a grammar

school in Santiago, a school very possibly connected with the Cathedral.

If in fact Jacobus

does not contain a special Santiago repertory, then what is the

justification for including the musical works here? There can be little

doubt about the relevance of the pilgrim song Dum pater familias.

As for the polyphonic works, I would suggest that at least some parts

of the Codex were of special interest and importance to the Spaniards.

Whatever the provenance of the material, the texts deal with St James

and the music is of a high standard, so it would be surprising if the

works remained unknown; and we can never know how many of the French

pilgrims to Santiago had received at least a part of their education

from the pages of Jacobus.

The polyphony of Jacobus

has presented musicologists with serious problems in the interpretation

of its rhythms because they attempted to apply the complex rules of

quite unsuitable modal or mensural rhythmic systems to a much more

simple style of notation. In fact, individual voice-parts display a

clear similarity to the syllabic style of the troubadour chanson. The occasional melismas, reminiscent of those found in the high-style chanson,

also reflect the flowing discant of the St Martial repertory. Vertical

lines in the manuscript help align voices, notes and text. The need to

apply too many complex rules would have made it quite impossible to

perform the music from the notation, but the most obvious and simple

approach works so well that it is difficult to imagine any other

solution! Each syllable or melisma takes one beat, with the occasional

lengthening of a note to accommodate more than one (clearly defined)

melisma in the other part.

CANTIGAS DE AMIGO

The seven Cantigas de Amigo

of Martim Codax, the 13th-century Galician juglar, are the earliest

surviving examples of Iberian secular music. Codax was possibly

connected with the court of Don Dinis of Portugal. His seven poems

appear in two manuscripts, one of them in the Vatican, but both without

music. In 1914 the Madrid bookseller Pedro Vindel discovered a third

manuscript in the binding of a 16th century copy of Cicero's De Officiis.

Here at last were melodies, though incomplete and corrupt, for six of

the Codax Cantigas. The parchment is torn and some of the notes are

missing or blurred, but it is clear from the notation that it dates from

around 1300. The scribe drew the staves for the sixth song, but

unfortunately did not fill in the notes.

The songs in this

manuscript appear in the same order as in the others, suggesting a

definite cycle — not a narrative, but variations on the same theme, and

possibly the first extant song cycle.

Although Vigo does not lie

on the Pilgrim Road, it is only a little way from Padrón, where the body

of St James is believed to have arrived in Spain. But for us there is a

far better reason for including the cycle here — these seven tiny,

simple and repetitive songs are among the most passionate and moving

pieces we have ever performed, and the cumulative effect of the cycle is

utterly devastating.

PÓRTICO DE LA GLORIA

The

apocalyptic vision of St John was widely illustrated in Romanesque and

Gothic churches and manuscripts, and the twenty-four Elders described in

the Book of Revelation appear frequently in church doorways,

particularly on the pilgrim roads to Santiago. In the biblical

description the Elders are each holding an instrument in one hand and a

vase of incense in the other. The relevant passages from the Vulgate and

in translation appear as follows:

Et...

vigintiquattuor seniores ceciderunt coram Agno habentes singuli

citharas et phialas aureas plenas odoramentorum, quae stint orationes

sanctorum.

(‘And round about the throne were four and twenty

seats; and upon the seats I saw four and twenty elders sitting, clothed

in white raiment; and they had on their heads crowns of gold...

And...

the four and twenty elders fell down before the Lamb, having every one

of them harps, and golden vials full of odours, which are the prayers of

saints’. Revelation IV.4, V.8)

I have long been fascinated

by the make-up of this particular medieval orchestra. Not only are the

stone carvings of the instruments incredibly detailed and accurate, but

there is also a certain sense and symmetry in the make-up of the group.

One cannot always dismiss medieval iconogaphy as artistic licence and

symbolism. True, pictures of music-making appear more realistic when

fewer musicians are involved, but I think it is dangerous to insist that

any large group of musicians — be they Angels or Elders — are unlikely

to represent actual medieval orchestras, but only symbolize heavenly

music to the glory of God. Surely some artists depicted instrumental

ensembles with which they had been familiar.

Jacobus has something interesting and perhaps enlightening to say on the matter:

Now

this description may have been exaggeratedly all-embracing for effect,

but even today in Morocco traditional ensembles consist of large numbers

of violins, some lutes, a rebab and percussion. So for this recording I

brought together what must be one of the largest medieval ensembles of

modem times (certainly the largest collection of medieval fiddlers) in

order to reproduce the make-up and sound of the Pórtico de la Gloria

ensemble as closely as possible. Given the limited availability of good

specialist players and instruments, it is as well that not all

twenty-four Elders on the Tympanum are actually holding instruments!

One

of the most important constituents of the group must be the

organistrum, and I was fortunate to enlist the aid and instrument of

Mary Remnant, music director of the Confratemity of St James and one of

the greatest authorities on the pilgrimage, its music, instruments and

architecture. Four 3-string ‘8-shape’ fiddles or medieval viols flanked

the organistrum, two on either side, then psaltery, zither (substituting

for the medieval rotta), harps, gittems, and finally 5- and 3-string

harps, gitterns, and finally 5- and 3-string fiddles played at the

shoulder.

What should the ensemble play? The most apt work in the repertory, Dum pater familias,

also presented the best material for such an ensemble — certainly the

melody offers many opportunities for embellishment and the improvisation

of extra parts and fuller textures.

Did the experiment work? We

all feel that it did, and not just well, but to an astonishing degree,

as did the use of large forces in other carefully chosen works. It

seemed natural, in the light of the description in Jacobus and

the size and make-up of some modern ethnic ensembles, to employ the

fiddle band in a few of the Cantigas de Santa Maria, with and without

other instruments and voices. De grad'a Santa Maria and Non e gran cousa have been discussed elsewhere, but it is worth pointing out here that the (unperformed) texts of Non sofre Santa Maria and Por dereito ten a Virgen, two Cantigas played by the fiddle band alone, concern pilgrims on the road to Santiago; and the wild instrumental prelude and interludes of Non e gran cousa are based on Cantiga 77, Da que Deus mamou,

which tells of a miracle at Lugo, a town situated a little to the north

of the pilgrim road soon after Triacastela in Galicia. It is now a main

centre for the manufacture of the Galician bagpipe known as gaita, to be heard throughout the region and particularly in Santiago.

GONZALO DE BERCEO

Gonzalo

de Berceo took his name from the village where he was born and where

the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla is still to be found. He never

left his native region, retaining strong connections with the

monasteries of San Millán and Santo Domingo de Silos, but was well

enough educated to be highly regarded by his fellows. He wrote at a time

of ecclesiastical retrenchment — the Church was actively strengthening

its sway by reaching the people through a revival of interest in local

shrines — and his works include Vidas and miracles of local

saints and of the Virgin Mary. He loved and respected the people and

managed, through his writings, to enlighten their confusion concerning

doctrine and scripture.

PERFORMANCE PRACTICE

Many

links connect European secular music of the middle ages with music of

the world of Islam. These influences came through contact with Persian

scholars, through the Crusades and through the Moorish occupations of

Spain and Sicily. It was particularly apparent in the western adoption

of instruments such as the lute, rebec, shawm and nakers.

In the

Islamic tradition, music functioned chiefly as a carrier of text.

Improvised accompaniment was an important ingredient of performance, and

elaborate procedures were developed for making a large and complicated

work out of relatively simple strophic material. Accompaniments were not

written down, but devised by the performer to suit the character and

subject matter of the text.

The format of the Arabic Nuba

is an excellent example of how a ‘complete’ performance of a medieval

song could have been constructed, particularly in a region like Spain

which had close links with Arabic culture.

First we might hear a

free instrumental improvisation where the musician checks the tuning,

establishes the tonal centre and possibly introduces fragments of the

material to be performed. This is immediately followed by a more

rhythmic and coherent introduction, and when at last the attention of

the audience has been successfully attracted the song begins. Soon there

is a change to more instrumental music (an improvised interlude), then

the song again, and so on until the conclusion.

Although we read

of simpler and less organised styles of performance in the more northern

reaches of Europe, many medieval writers tell of singers accompanying

themselves with harp or fiddle, and improvising preludes, interludes and

postludes to their songs.

As to the general question of

instrumental involvement in the performance of monophonic song, it is

essential to approach the problem from the points of view of style,

function, geography, and in particular genre. Although the evidence is

fragmentary it is possible to deduce discernible patterns — certain

genres are particularly associated with instrumental participation,

while others are not.