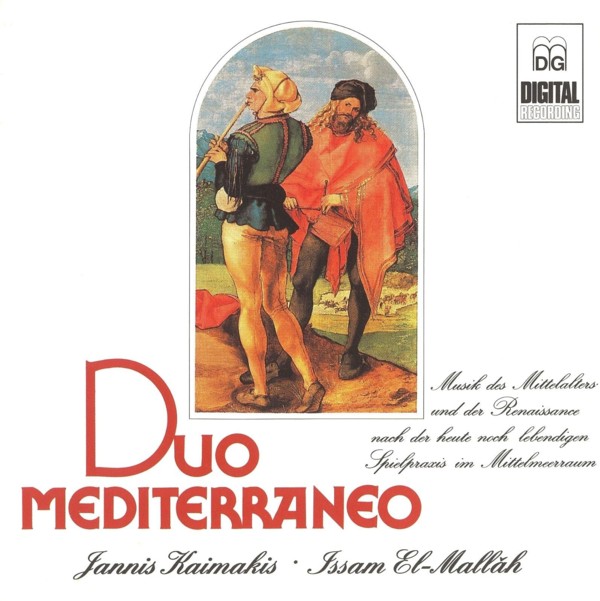

Musik des Mittelalters und der Renaissance / Duo Mediterraneo

nach der heutenoch lebendigen Spielpraxis im Mittelmerraum

medieval.org

Dabringhaus und Grimm MD+G L 3225

1988

1. Improvisation über mittelalterliche Melodien [2:33]

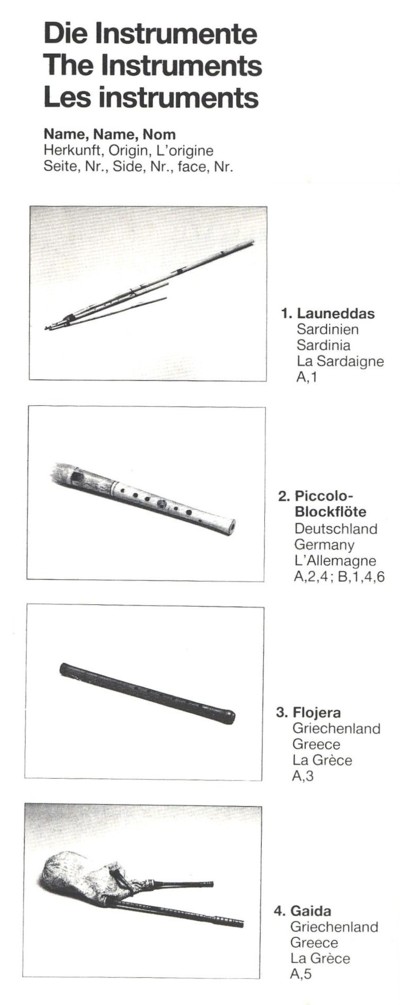

Launeddas

2. La Ultime Estampie Real [2:53]

Paris, Bibl. Nat., ms. franc. 844, fol. 104v (13. Jh.) —

Piccolo-Blockflöte, Riqq

3. Tou Kastrou tis Orias, Tris Kalogeri Kritiki [4:29]

Griechische Volkslieder, Mündliche Überlieferung —

Flojera, Duff

4. Saltarello [3:08]

Hs. Lo Brit. Mus., Add. 29987 (14.-15. Jh.) —

Piccolo-Blockflöte, Bongos

5. Reigentanz aus Makedonien [3:49]

Mündliche Überlieferung —

Gaida, Tabla

6. Chanson à refrain [2:35]

Anonymus, 13. Jh. —

Panflöte, Bandir

7. Heinrich NEWSIDLER. Wascha mesa [3:37]

»Ein Newgeordnet Künstlich Lautenbuch« (16. Jh.) —

Renaissance-Laute, Taar

8. Trotto [2:01]

Hs. Lo Brit. Mus., Add. 29987 (14.-15. Jh.) —

Piccolo-Blockflöte, Taar

9. Istampita Ghaette [6:52]

Hs. Lo Brit. Mus., Add. 29987 (14.-15. Jh.) —

Tanbura, Bongos

10. Lamento di Tristano un Rotta [3:14]

Hs. Lo Brit. Mus., Add. 29987 (14.-15. Jh.) —

Krummhorn, Bandir, Riqq

11. Estampie [2:50]

Trouvère-Lied »Souvent suspire Moncuer« (12-13. Jh.) —

Piccolo-Blockflöte, Taar

12. Improvisation über arabische Rhythmen [4:44]

Bongos

13. Omorfoula [1:38]

Griechische Volkslieder, Mündliche Überlieferung —

Piccolo-Blockflöte, Riqq

14. Como poden per sas culpas [5:05]

CSM 166

virelai aus »Las Cantigas de Santa Maria« (13. Jh.) —

Gemshorn, Tabl-Baladi

DUO MEDITERRANEO

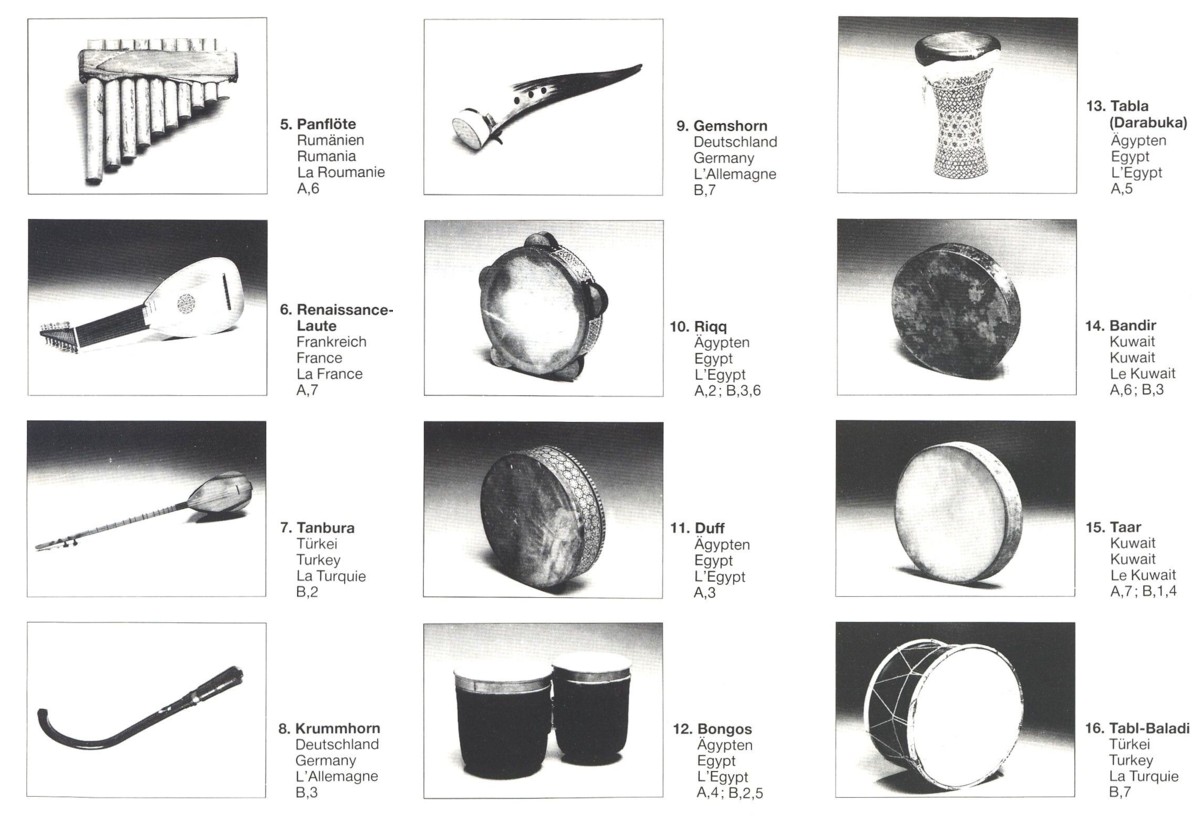

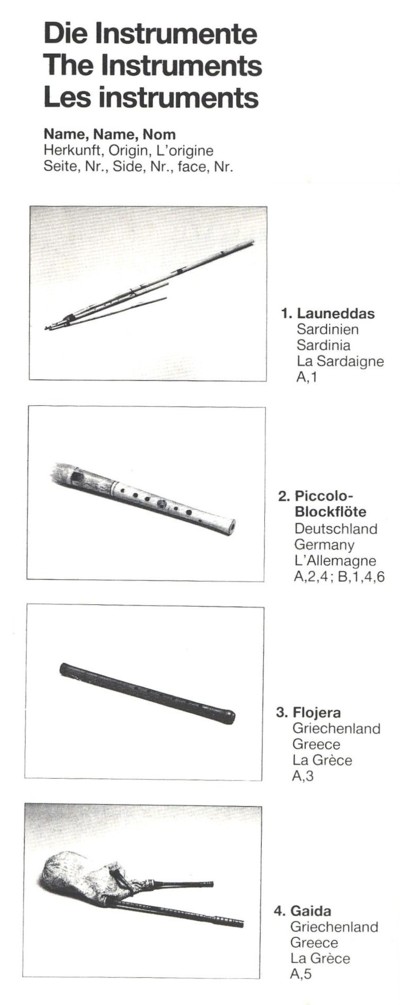

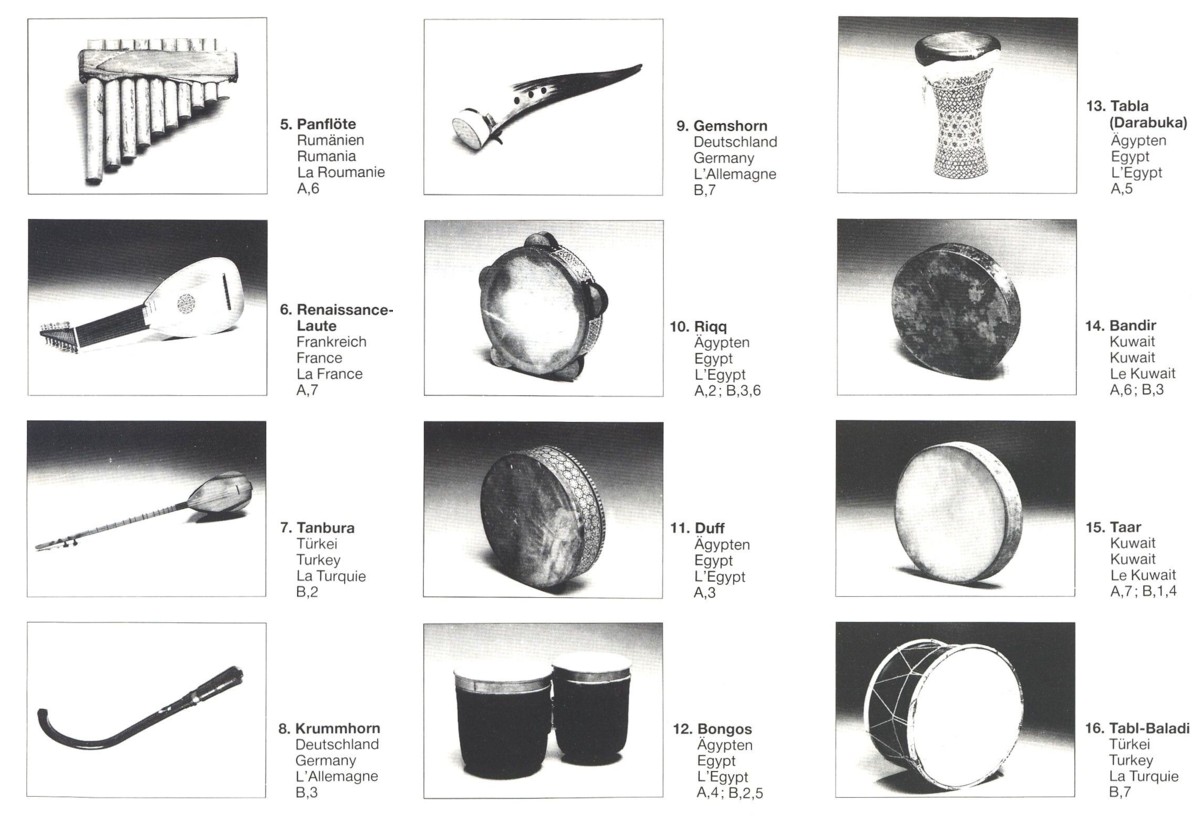

Jannis Kaimakis · Launeddas, Piccolo-Blockflöte, Flojera, Gaida, Panflöte, Renaissance-Laute, Tanbura, Krummhorn, Gemshorn

Issam El-Mallâh · Riqq, Duff, Bongos, Tabla (Darabuka), Bandir, Taar, Tabl-baladi

Aufnahme: Schloß Nordkirchen am 3.7.1985

Text: Dr. Issam El-Mallah, Universität München

Titelbild: Albrecht Dürer: Pfeifer und Trommler · (Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Köln) · Gestaltung: Peter Schulz

Aufnahmeleitung, Technik und Schnitt: Musikproduktion Dabringhaus und Grimm, Detmold

℗ 1988

The interpretation of medieval-and Renaissance music:

The interpretation of medieval-and Renaissance music:

The

performance of medieval music presents a great challenge to the

musician. In contrast to modern scores the written notes do not give the

slightest indication towards their adequate performance. In many cases

only the basic outline of a melodic line is written down and needs to be

completed by the instrumentalist. Medieval notation did not provide

detailed instructions for its performance but served only to preserve a

basic sketch of the piece. The modern performer has here the rare

possibility to act not as a reproducing but as a creative musician and

to contribute an essential element to the piece. Whilst studying a

manuscript containing medieval dances one finds for example that the

scanty melodic line needs to be completed by improvising and that no

rhythm at all is recorded. Yet dance without rhythm is inconceivable.

The rhythm was so obvious to the musician of that period that it was not

written down but simply added to each performance. The written notes

therefore need to be completed by adding a rhythm instrument to the

ensemble.

This theoretical knowledge alone does not help much

further if one cannot find musicians who can perform the music itself.

The overwhelming majority of Conservatoire and Music Academy graduates

are trained to perform music written during the last 250 years, most of

them are therefore unable to make use of the creative possibilities

offered by medieval music. Musicians who grew up in southern- or in

non-european countries have a more intensive relationship to the nature

of a medieval musician. In Egypt, for example, a melody is still only

sketched in its basic outline even today, if it is written down at all.

The rhythm, although a vital element in Arabian music, is never written

down but is at the most implied by the type of piece sketched.

The Program:

The

selected pieces of music cover a period of 400 years, beginning with

the Middle Ages (13th century) up to the Renaissance (16th century).

Though an instrumental ensemble, the Duo Mediterraneo also plays vocal

music: vocal compositions are being interpreted instrumentally in

medieval minstrel manner. Thus, besides many a dance, you will hear a

virelai (B7/#14), a chanson (A6/#6), and a trouvére song (B4/#11). Some

Greek dances (A5/#5) and songs (A3/#3 and B6/#13) as well as a few

Arabian rhythms (B5/#12) demonstrate the parallelism between the Greek

and Egyptian style of performance on the one side and the European on

the other side.

The Duo Mediterraneo:

The Greek

Jannis Kaimakis und the Egyptian Issam EI-Mallah met at Munich

University where both were studying musicology. Since its foundation in

1900, the Munich Institute of Musicology is being concerned with studies

in the field of medieval music; particular emphasize is given to the

study of old music sheet and their interpretation. Through the studies

in Munich University and by their own experience in their native

countries Jannis Kaimakis and Issam El-Mallah discovered the parallelism

between life music execution in Egypt and Greece at present, and the

performance style that must have been practised in the Middle Ages. The

two musicians punctuate the rhythm with the percussion instruments and

colour the melody by vamping, just as this still is being done in their

homeland. They apply this Mediterranean practice when playing medieval

music, and this way of playing music underlines the minstrel character

of their performance.

The Duo Mediterraneo plays 20 different

instruments, mainly from the Mediterranean region where these

instruments still have not lost their function in cultural life.

The interpretation of medieval-and Renaissance music:

The interpretation of medieval-and Renaissance music: