Faventina / Mala Punica

The liturgical music of Codex Faenza 117, 1380-1420

medieval.org

Ambroisie AM 105

julio de 2005

Bologna

ordinarium

missae

01 - Kyrie Cunctipotens genitor Deus, ff.79r-79v [0:49]

02 - Kyrie Cunctipotens genitor Deus, ff.88r-90r [5:48]

03 - Gloria, ff.90r-92v [5:20]

04 - Kyrie Fons et origo, ff.2r-3r [4:19]

05 - Alleluja. Ego sum pastor bonus, I-Gua, f.194v [3:54]

06 - Kyrie Orbis factor, ff.62r-26r [3:16]

cantasi come

07 - Nostra avocata sei, cantasi come Deduto sei,

Vat266, f.32v, ff.46v-48r [5:39]

08 - Per verita portare, cantasi come Non al suo amante,

I-Ricc2871, f.59v [3:58]

09 - Non al suo amante, ff.78r-79r [2:14]

ad vesperas

10 - [Deus in adjutorium meum intende], ff.93r-94r [4:12]

11 - Antiphona. Hec est regina, I-SM572, f.141r - psalmus. Laudate

pueri Dominum [1:09]

12 - Ave maris stella, ff.96v-97r [1:19]

13 - Antiphona. Ave regina celorum, I-SM574, ff.109v-110r

[1:49]

14 - Magnificat, ff.95r-96v [8:21]

15 - Sicut erat in principio, cantasi come [Soventt mes

pas], f.94v [4:22]

16 - Benedicamus Domino, Deo gratias, ff.79r-79v [1:30]

17 - Benedicamus Domino, 79r-79v [2:19]

18 - Benedicamus Domino, 57r-58r [4:05]

Sources:

Fa117: Faenza, Biblioteca Comunale Manfrediana, ms. 117

I-Gua: Guardiagrele, Chiesa di S. Maria Maggiore, cod. 1

Vat266: Roma, Biblioteca Vaticana, ms. Chig. 266

I-Ricc2871: Firenze, Biblioteca Riccardiana, ms. 2871

I-SM572: Firenze, Museo di San Marco, ms. 572

I-SM574: Firenze, Museo di San Marco, ms. 574

MALA PUNICA

Pedro Memelsdorff

Tina Aagaard, Barbara Zanichelli - sopranos

Alessandro Carmignani, countertenor

Gianluca Ferrarini, Raffaele Giordani, Juan Sancho - tenors

Pablo Kornfeld, organ, clavicymbalum

Guillermo Pérez, organetto

David Catalunya, organ, clavicymbalum

Helena Zemanová, fiddle

Angélique Mauillon, harp

Pedro Memelsdorff, recorder

Faventina, the

liturgical music of Codex Faenza 117

by Pedro Memelsdorff

Musical glosses

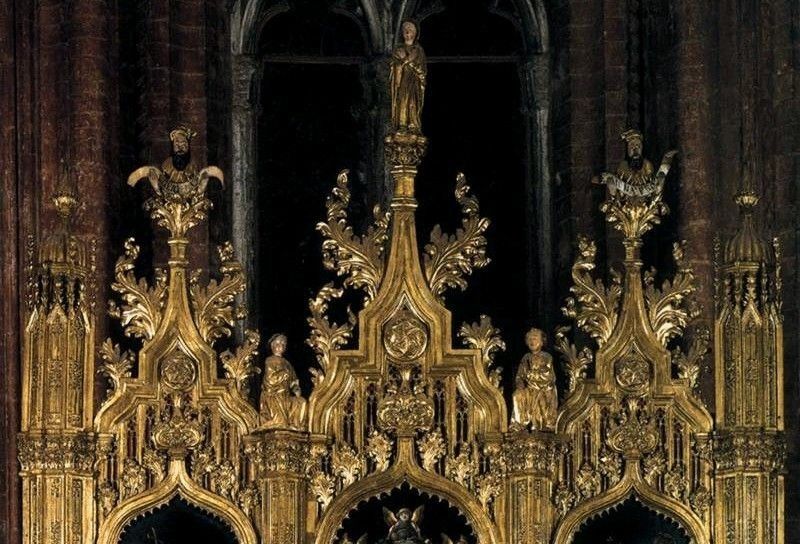

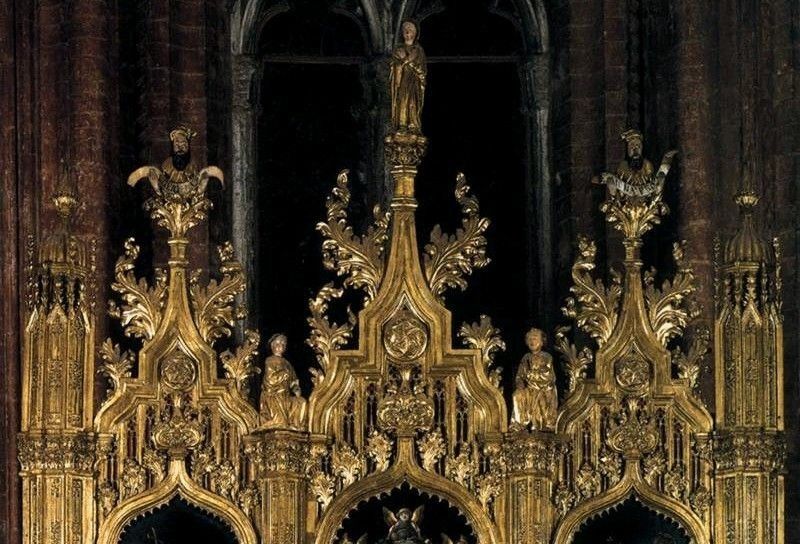

The carvings on a gilt frame, much like the marginal decorations of a

page - shapes, figures, stories - can explain and illustrate, or on the

contrary contradict and discredit, even desecrate the very picture that

they enclose - or the main text of the page on which they are found.

And the same may occur with the various types of marginal writings or

glosses: explanations or comments, elucidations or criticisms of a word

or a passage, whose study stands at the crossroads between the history

of manuscript transmission, textual critique, and intellectual history,

and can reveal in an extraordinary way a text's impact, its reception

upon coming into contact with various cultural contexts. What are musical

glosses?

Two centuries before Ortiz or Mudarra used the term gloss in

their anthologies, several musical cultures - among them Italian Ars

nova - developed a tradition of substituting (or completing) simple

melodies with ever richer and more complex variations: comments,

illustrations, 'explanations', 'critiques' of a more or less

recognisable - or memorised - original melody.

The repertoire presented here is made up exclusively of the musical

glosses or Ars nova diminutions that are found in the

manuscript 117 of the Biblioteca Comunale Manfrediana of Faenza, the

renowned 'Codex Faenza'.

The manuscript

Few manuscripts of the Italian Ars nova have received more

attention (and given rise to more controversies) than the Codex Faenza

- controversies regarding style, but above all organology and

performance. It is thus surprising that even today there is no

complete, codicological, philological and historical study of the

source. Nor has there yet been attempted a complete recording of it.

Made up of 98 parchment folios organized in ten irregular fascicles,

the Codex Faenza was prepared at one time in a single scriptorium,

but subsequently manipulated by four scribes, before (or during) its

compilation - which may perhaps be dated to central-northern Italy

around 1400-1420. Then - between 1473 and 1474 - the old notation was

partially erased and written over by a Carmelite musician and theorist,

itinerant among the Carmels of Mantua, Reggio Emilia and perhaps

Ferrara: Johannes Bonadies, to whom we owe the current 'title' of the

manuscript, 'Bonadies, Regulae cantus'.

The repertoire copied by the four earlier scribes consists of fifty intabulated

instrumental diminutions: directly below each stave of diminution lies

the respective tenor, creating a kind of 'score' which allows -

when so desired - a synchronic reading of the polyphony on behalf of

one single individual. Indeed, clear signs of coeval wear and tear

demonstrate the assiduous use of the diminutions directly from

the manuscript: Codex Faenza was (also) a 'score' designed for

practical use. The quantity of scribal corrections is therefore not

surprising: slight - and sometimes large - erasures and over-writings

were carried out by the scribes themselves to remedy errors of

transcription (or lapses of memory), whose deconstruction leads to some

striking conclusions. The first is the non-intabulated origin of the

greater part of the material: Faenza was mostly copied from (now lost)

non-intabulated exemplars, that is, exemplars intended for collective

use. The second is the considerable cultural distance that separates

the four copyists from the repertoire copied: the diminutions of Faenza

must date back, at least in part, to the latter decades of the

fourteenth century.

The sacred repertoire

Three of the four scribes were involved in the transcription of the

liturgical repertoire, which consists of diminutions for three pairs of

Kyrie-Gloria (Vat. IV and XI), a single versicle of Kyrie

(Vat. IV), two Benedicamus domino and various sections of an

extraordinary Marian Vespers, which is in fact the earliest polyphonic

Vespers to have come down to us. Here we present, for the first time, a

complete recording of all this material - including some newly restored

segments of one of the Kyrie (on f. 3r), and one piece totally

unknown until now: the Kyrie Orbis factor of the ff. 62r-v and

26r (palimpsest), completely erased and written over by Johannes

Bonadies in 1474. Our digital restorations have allowed the recovery

and virtually complete transcription of this piece, and suggested a new

historical and cultural context for the Faenza diminutions in

general. Unlike the mass Cunctipotens genitor deus (Vat.

IV), intended for occasions of particular liturgical importance, Orbis

factor (Vat. XI) was a mass of weekly use: the praxis of polyphony

and diminutions such as the ones in Faenza must therefore have been a

much more frequent phenomenon than has hitherto been suspected. Such a

praxis conformed to the tradition of late medieval liturgical chant,

which allowed for diverse performance possibilities, among them the cantus

planus (or Gregorian), the cantus fractus (Gregorian in a

rhythmic vest), the cantus binatim (Gregorian accompanied by

simple polyphonies) and the cantus alternatim (alternation

and/or combination between instruments, cantus planus and/or cantus

binatim).

Little - or better yet, almost nothing - is known with precision as

regards the practice of this cantus alternatim around the

chronological period and possible geographical collocation of the

Faenza codex; furthermore, the documents of succeeding centuries are of

scarce - or no - use. These latter include descriptions and sometimes prohibitions

of the synchronic and/or successive performance of instrumental and

Gregorian versions - indicative, perhaps, of a rich and many-sided

tradition.

It therefore becomes quite interesting to read the rare and eloquent

description offered to us by the Florentine chronicler Filippo Villani,

written in 1381:

"When in our greater church the Credo was sung in part with the

organ and in part with the choir, [the organist] Bartolo performed it

with such sweet sound and artistic mastery that, upon having abandoned

the usual alternation of the organ, he sung it with the great support

of the people who followed the natural harmony with living voices one

after the other. So, before any other, he brought about the elimination

of the antique practice of the male choir and the organ."

Our proposal

This extraordinary testimony of a wholly vocal performance -

not incompatible, rather synchronous with the instrumental suaves

dulcesque soni - has led us to implement each of the following

hypotheses: alternatim between cantus planus and

soloist diminutions (Kyrie Orbis factor); between cantus

binatim and collective diminution (Kyrie Fons et origo);

between cantus planus and diminutions that are synchronic with

the cantus binatim (Kyrie-Gloria Cunctipotens, Vespers).

In the reconstruction of the Vespers, furthermore, several lines of

research on the pieces now on the ff. 93r-94r and 94v. have been taken

into consideration. The first of these, identified on our behalf, is

without doubt the diminution of a sacred or celebrative isorhythmic

motet, heavily influenced by Veneto and post-Ciconia styles. Its two

original vocal lines, isomorphic and imitative, probably bore two

different texts, now irreparably lost; but its position in the

manuscript, immediately before the Magnificat, suggests a tenor

based on a Marian antiphon, or - as we have hypothesised - on the Deus

in adjutorium. The second piece is a diminution of the bassadanza

also known under the title Soventt mes pas (included in the

chronicle of the ms. London, BM Cotton Titus A XXVI, datable to the

1440s). What is more, its position in the tenth fascicle of Faenza 117

- symmetrical to that of the bassadanza Collinetto, placed

before the Benedicamus of fascicle VI - only confirms the

hypothesis recently aroused by iconographical studies on the late

medieval lauda-ballate: the existence of forms of dance contrafacta

intended for the conclusion of masses or offices. Therefore, given the

striking resemblance between Soventt mes pas and the doxology

of the fifth tone, our hypothesis is that of a contrafactum of

the Gloria patri sung - or rather danced - to the tenor

of the bassadanza.

We are well aware that our point of view - and of listening - could

overturn some current interpretations (or prejudices) regarding both

repertoires, Faenza and the late medieval Gregorian chant, generally

held to be purely soloistic or purely monodic,

respectively.

Nevertheless, no fourteenth- or fifteenth- century proof of such a

presumed 'neo-medieval purity' is known to us. On the contrary, both

polyphonic improvisation on the Gregorian chant and the collective use

of instrumental diminutions have left many traces in the scribal

praxis, which has encouraged us to pursue these and other forms of

experimentation. Not least those on the laude: Faenza 117 contains a

great number of diminutions on secular pieces (both French and

Italian), of which other sources preserve the texts of sacred contrafacta

- the well-known cantasi come ('to be sung like...'). Two of

these diminutions have been included here: one on the madrigal by

Jacopo da Bologna Non al suo amante - of whose text, by

Petrarch, an admirable contrafactum is preserved in the

Biblioteca Riccardiana of Florence - and one on the famous lascivious

ballata Deduto sei by Antonio Zacara da Teramo. The contrafactum

of its text, taken from a well-known manuscript now at the Vatican

Library, seems to be the result of a real 'depuration' or almost -

considering the symmetrical location of the terms and the senses to be

'depurated' - a genuine 'exorcism' of the original text. We have no

knowledge of the liturgical or para-liturgical function of the

(possible) laude settings of Faenza. But Non al suo amante

- let us remember - is followed by the Kyrie of f. 79.

The group of instruments that we propose includes - beyond the

extremely sporadic use of two melodic instruments, the fiddle and the

recorder - three families of late medieval keyboards: organs, organetti

e clavicymbala. The first two have been reconstructed on the

basis of the corpus of figurative iconography, while the third has been

recreated on the basis of Arnold van Zwolle's exceptionally precise

drawings - preserved in the Ms. Lat. 7295 of the Bibliothèque

Nationale of Paris - datable to the 1440s. The temperament is

Pythagorean and the pitch is that of the oldest central-northern

Italian documents: A = 520.

These words cannot suffice - our hope is that the sounds will

recompense - to express our deepest gratitude towards the Biblioteca

Comunale Manfrediana of Faenza, which has been of such precious aid

during our many years of research on the manuscript.