medieval.org

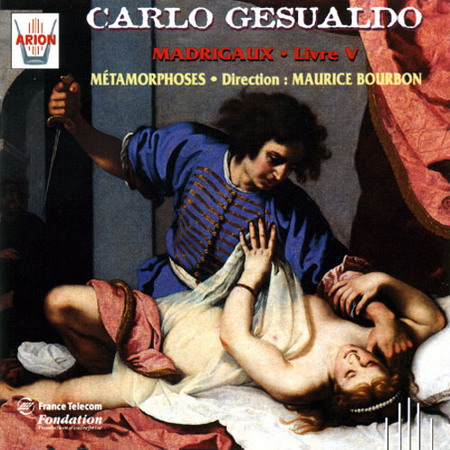

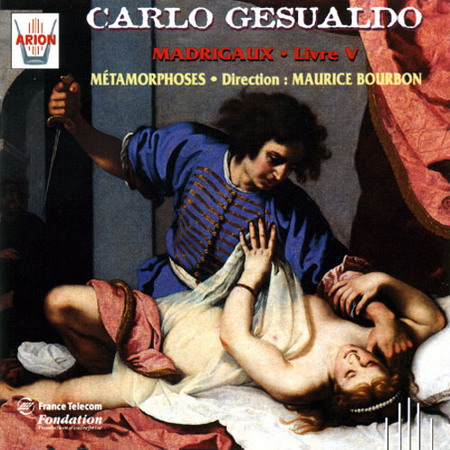

Arion ARN 68388

1996

medieval.org

Arion ARN 68388

1996

01 - Gioite voi col canto [2:59]

02 - S'io non miro non moro [2:57]

03 - Itene, o miei sospiri [3:37]

04 - Dolcissima mia vita [2:38]

05 - O dolorosa gioia [3:10]

06 - Qual fora, donna, un dolce 'ohimè' [2:06]

07 - Felicissimo sonno [2:50]

08 - Se vi duol il mio duolo [3:17]

09 - Occhi del mio cor vita [2:35]

10 - Languisce al fin chi de la vita parte [3:40]

11 - Mercè grido piangendo [4:06]

12 - O voi, troppo felice [1:39]

13 - Correte, amanti, a prova [3:01]

14 - Asciugate i begli occhi [3:41]

15 - Tu m'ucchidi, o crudele [3:01]

16 - Deh, coprite il bel seno [2:10]

17 - Poichè l'avida sete [2:39]

18 - Ma tu, cagion [2:23]

19 - O tenebroso giorno [2:12]

20 - Se tu fuggi, io non resto [2:01]

21 - 'T'amo mia vita', la mia cara vita [2:32]

ENSEMBLE MÉTAMORPHOSES

Maurice Bourbon

SOLISTES

Daphné KUPFERSTEIN, soprano - madrigaux #1-4, 11-13, 20

Claire GOUTON, soprano - madrigaux #3-10, 13-18,

Pascale COSTANTINI, mezzo-soprano - madrigaux #1-2, 5-7, 9-11, 14-16,

19-21

Jacques MAES, contreténor - madrigaux #1-21

(tous)

Éric TREMOLIÈRES, ténor - madrigaux #1-3, 8, 13,

16-18, 21

Éric RAFFARD, ténor - madrigaux #4-12, 14-15, 17-19

Maurice BOURBON, baryton - madrigaux #1-4, 10-16, 20-21

Philippe ROCHE, basse - madrigaux #5-9, 17-19

Assistance a la prononciation italienne: Annie Moreau

Avec le fidèle soutien amical de Christiane Toudoire

De gauche a droite:

Maurice Bourbon, Pascale Costantini, Daphné Kupferstein, Jacques

Mars, Claire Gouton, Éric Raffard

CARLO GESUALDO

«... I met the Prince at the ferry... He has it in mind to

beseeth Your Highness most warmly that tomorrow evening you will permit

him to see Signora Donna Leonora. In this he shows himself extremely

Neapolitan. He thinks of arriving at twenty-three o'clock, but I doubt

this because he does not stir from his bed until extremely late.

... The Prince, although at first view he does not have the presence of

the personage he is, becomes little by little more agreeable and for my

part I am sufficiently satisfied of his appearance. I have not been

able to see his figure since he wears an overcoat as long as a

nightgown; but I think that tomorrow he will be more gaily dressed. He

talks a great deal and gives no sign, except in his portrait, of being

a melancholy man. He discourses on hunting and music and declares

himself an authority on both of them. Of hunting he did not enlarge

very much since he did not find much reaction from me, but about music

he spoke at such length that I have not heard so much in a whole year.

He makes open profession of it and shows his works in score to

everybody in order to induce them to marvel at his art. He has with him

two sets of music books in five parts, all his own works, but he says

that he only has four people who can sing for which reason he will be

forced to take the fifth part himself ...

He says that he has abandoned his first style and has set himself to

the imitation of Luzzasco, a man whom he greatly admires and praises,

although he says that not all of Luzzasco's madrigals are equally well

written, as he claims to wish to point out to Luzzasco himself. This

evening after supper he sent for a cembalo so that I could hear

Scipione Stella,... But in all Argenta we could not find a cembalo for

which reason, so as not to pass an evening without music, he played the

lute for an hour and a half. Here perhaps Your Highness would not be

displeased if I were to give my opinion, but I would prefer with your

leave, to suspend my judgement until more refined ears have given

theirs. It is obvious that his art is infinite, but it is full of

attitudes, and moves in an extraordinary way. However, everything is a

matter of taste. This Prince then has himself served in a very grand

way ...

So much and no more shall I say for the time being to Your Highness,

reserving to relate in person the most important discourses made to me

by His Excellency... (1)»

From Count Alfonso Fontanelli,

to Duke of Ferrara, 18 February 1594

«As to music, he sings his part by the book in as pleasing a

manner as a gentleman can. He has rather a good tenor voice. He also

sings the soprano part, but the voice is not so pure in this range,

even though graceful. He plays the basso di viola exquisitely, however,

and he touches the strings with much grace ...» (1)

From Count Alfonso Fontanelli

to Duke of Ferrara, 9 October 1594

CARLO GESUALDO: HIS LIFE

Were it not for his two marriages, which, for very different reasons

and, in both cases, only for a short period of time, brought him very

much into the public eye, we today would know very little about Carlo

Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa—apart, perhaps, from his music.

Indeed, Gesualdo's life may be divided into four periods, the two

shortest of which (the second and the third) were the richest and are

also the best-known.

C. 1560 to 1590: youth and first marriage

Carlo Gesualdo was born in about 1560, probably in Gesualdo, near

Naples. Although he showed signs of an aptitude for music, there was

nothing to hint, in those early years, that he was later to become such

a brilliant composer: by the age of thirty, in 1590, he had composed

practically nothing. Only two important events punctuated that period:

in 1585, his elder brother died, leaving him heir to the family title,

and in 1586 he married the lovely Donna Maria d'Avalos, who, at the age

of twenty-five, had already been widowed three times.

16 October 1590 - 18 February 1594: assassination of his first wife

and plans for a second wedding

Aware that his wife was unfaithful, Gesualdo artfully laid a trap, and,

on the night of 16 October 1590, he had both her and her lover brutally

murdered, then left their bodies on show on the palace steps for

several days. Even for a prince, it was probably not good form to kill

one's wife at that time, and Gesualdo seems to have kept a low profile

for the next three years. We know only that he had a chapel (dedicated

to Santa Maria delle Grazie) built on his estate, no doubt in atonement

for the incident. The altarpiece from this chapel includes a very

detailed portrait of Gesualdo, the only one that is known. He also

composed his first and second books of madrigals during that time.

Meanwhile, for reasons of interest, his uncle, Cardinal Alfonso

Gesualdo did his utmost to arrange a second marriage between his nephew

(who was at first clearly unkeen on the idea) and Leonora d'Este, the

daughter of the Duke of Ferrara. The marriage was finally contracted on

20 March 1593 and the wedding took place on 19 February 1594.

19 February 1594 - 1596: second marriage; a period of interesting

encounters

On 18 February 1594 Carlo Gesualdo thus approached Ferrara. He was met

and accompanied on the last stretch of the journey by Count Alfonso

Fontanelli, who had been appointed his equerry by the Duke of Ferrara

and who wrote his first 'report' on that day: Gesualdo is shown as a

man of rather uncouth appearance, clearly an authority on music, a man

of many parts, boastful, extravagant, indolent, no doubt temperamental,

and in any case extremely original.

The wedding to Leonora d'Este took place on the following day, 19

February 1594, and the next two years were the most brilliant and most

fruitful of Gesualdo's life. During that time, the 'poor' nobleman from

the South discovered the wealth, munificence and intense intellectual

and cultural activity of one of the great courts of Italy.

Gesualdo had already become friends with Torquato Tasso several years

previously. In Ferrara he met other poets, and, above all, other

musicians, including Luzzasco Luzzaschi for whom he had great

admiration and whose influence was to be clearly felt in his third and

fourth books of madrigals, composed in Ferrara and published in 1596.

In 1594, during visits to Venice and Naples, and in 1595-96, during a

second stay in Ferrara, Gesualdo was to meet a whole host of musicians,

including Giovanni Gabrieli, for certain, and probably also De Wert,

Monteverdi, Vecchi and Caccini.

1597 - 1613: his return to Gesualdo, neurasthenia and death

In 1597 Carlo Gesualdo entered a much greyer period, with a succession

of unhappy events, changes in his financial position, and fits of ill

humour and aggressive behaviour. On his return to Gesualdo, he

gradually withdrew into his neurasthenia. His health was rather

fragile, he was apparently asthmatic, and in his fits of madness he

would vent his anger on his wife, beating her, then seeking redemption

by inflicting corporal punishment on himself. To make matter worse, his

four-year-old son died in 1600. From then on, he seems to have lived

the sombre life of a recluse until his death in 1613, punctuated only

by the publication of his Sacrae Cantiones (1603), his fifth

and sixth books of madrigals and his set of Responsoria (1611).

GESUALDO'S SECULAR

WORKS

Gesualdo was truly a musician of his time and a perfect Italian

madrigalist, in that he observed the rules of the genre, central to

which was the art of text-painting: high notes for a cry, low notes for

silence, irregular melodies and harmonies to express torment and

suffering, sombre colours for death, bright, light colours for joy and

for fire, etc. Only love is ambiguous, providing Gesualdo with an

excuse to indulge in his favourite pastime: the expression of

'exquisite heartbreak'.

Gesualdo would thus be very similar to his contemporaries if he did not

leave his own personal stamp on every phrase and every detail. He

discovered mannerism and chromaticism through Nenna and Luzzaschi, in

particular, but not only did he adopt that movement, but he also

transcended it, leaving behind the mark of his genius. He was extremely

keen on harmony, which is why his works have such appeal. At very first

sight, however—in this field as in others—he seems to be

quite tame: like any other composer of his time, he uses either no

chromatic alteration at all in his key-signatures or just one flat. But

this apparent simplicity opens up the door to real freedom, and we then

find a deluge of accidentals (he uses practically all the sharps and

all the flats), which enables him to build up a harmony, a veritable

musical poetry, the like of which is not to be found elsewhere in the

whole of the history of music.

THE FIFTH BOOK OF

MADRIGALS

Gesualdo's first two books of madrigals, published before his arrival

in Ferrara, are quite conventional. Innovation and originality appear

with the third and—especially—the fourth books, written in

Ferrara between 1594 and 1596. For this interpretation, however, our

choice fell quite naturally on the fifth book—a real masterpiece,

possibly written in 1596 (as the introduction to the edition of 1611

seems to attest), i.e., just after Book Four. This interval of fifteen

years between the composition of the madrigals and their publication,

and the short space of time that it would suppose between the

composition of the fourth and fifth books, is very surprising, for

there is a great difference in style and skill between the two works.

The origin of the texts is unknown, with the exception of 'T'amo mia

vita', which is by Guarini. Other unattributed poems were set to music

by other composers of the time, including Monteverdi (Occhi del mio cor

vita). Others still may have been written by Gesualdo himself.

The pieces in the set are well-balanced, with a perfectly coherent key

sequence and a practically unflagging intensity in the scoring. Among

the culminations of Gesualdo's passion and originality, we may mention

the 'death' at the end of the madrigal no. 4 ('Dolcissimo...'); the

'painful joy, sweet pain' at the beginning of the no. 5 ('O0

dolorosa...'); the whole of the magnificent madrigal no. 8 ('Se vi

duol...'), in which sorrow, joy and, finally, fire lead to peace;

another amazing death at the end of no. 11 ('Mercè...'); the

tears and unhappiness of the second part of no. 14 ('Asciugate...');

the sumptuous harmonic progression in no. 17 ('Poi che...'); the

shadows at the beginning of no. 19 ('O tenebroso...'); the brisk flight

at the end of no 20 ('Se tu fuggi...').

OUR READING

Each madrigal is sung by five soloists a cappella. In our opinion, this

was the only formula that was capable of doing justice to the

complexity of the music and, above all, to its harmony. Indeed, the

endless changes of key mean that the performer has to be constantly in

touch with the 'verticality' (harmony) of the pieces; and in this the

soloist has an advantage over a group of singers, in having greater

flexibility and being able to make very swift adjustments.

Within each madrigal, each tessitura is quite well-defined and can

easily be held by one singer. However, as the tessitura varies greatly

from one madrigal to another, a team of eight singers was required for

the performance of the whole set. In order to preserve the obvious

tonal balance of the book, none of the madrigals have been transposed.

We have chosen the frequency of A=440 hertz.

Maurice BOURBON

Translation. Mary PARDOE

.......

(1) In Gesualdo, The Man and His Music, by Glenn Watkins

(Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991)