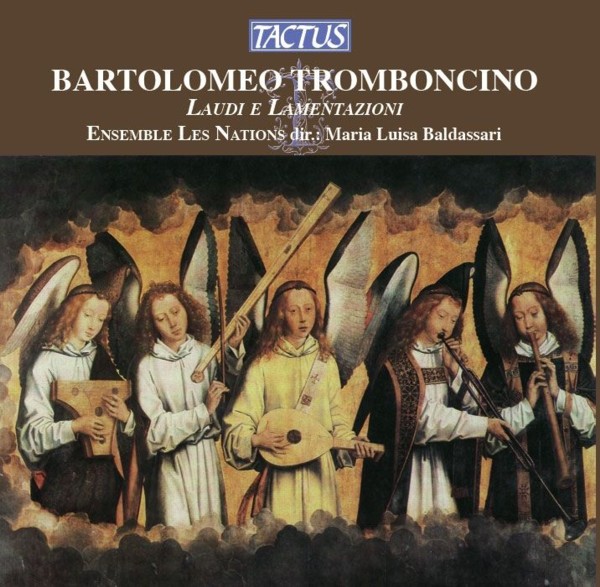

Tactus TC 472001

1998

reedición 2006

Tactus TC 472001

1998

reedición 2006

Bartolomeo TROMBONCINO

(c.1470-c.1535)

Laudi e Lamentazione

01 - Ben sarà

crudel e ingrato [5:11]

02 - O sacrum convivium [2:49]

03 - Adoramus te, Christe [2:40]

04 - Sancta Maria [2:26]

05 - Ave Maria 48 [2:26]

06 - Ave Maria, regina [2:46]

07 - Ave Maria 40 [2:27]

08 - Vergine bella [2:45]

09 - Ave Maria 47 [2:30]

10 - Tu se quell'advocata [5:34]

11 - Lamentationes Jeremiae Prophetae [10:58]

12 - Eterno mio signor [1:51]

13 - Per quella croce [2:22]

14 - Salve croce [5:04]

15 - Arbor victorioso [2:31]

16 - L'Oration è sempra bona [1:28]

Ensemble LES NATIONS

Maria Luisa Baldassari

Stefano Albarello,

cantus

Matteo Zenatti, tenor/altus, arpa diatonica

Massimiliano Pascucci, tenor/altus

Marco Scavazza, bassus

Paolo Fanciullacci, cornetto e cornetto muto

Luigi Lupo, traverse

Paolo Faldi, bombarda, flauto dolce contralto e tenore

Pamela Monkobodzky, flauto dolce contralto e tenore

Mauro Morini, trombone

Alberto Santi, dulciana

Stefano Rocco, liuto

Maria Luisa Baldassari, organo

Bartolomeo Tromboncino (Verona ca. 1470

- Venezia post 1535) compare sui testi musicologici soprattutto come

compositore di musica profana; a lui e al suo collega Marchetto Cara si

deve buona parte della produzione frottolistica nata fra il XV e il XVI

secolo sotto gli auspici di Isabella d’Este a Mantova dove

entrambi servirono per lungo tempo. L’interesse dei musicologi

per la frottola e l’importanza dell’opera di Tromboncino in

questo settore hanno concentrato gli studi sulle sue composizioni

profane, considerate principalmente in una prospettiva di evoluzione

stilistica. Quasi completamente ignorati rimangono invece gli

interventi in campo sacro, che condividono peraltro il destino comune a

tutta la produzione sacra di autori italiani fra ’4 e ’500,

messa in ombra dal preponderante interesse per l’attività

dei musicisti fiamminghi. Se si escludono le introduzioni alle edizioni

e poco altro non esistono scritti specifici sulle laude di Tromboncino,

che si rivelano tuttavia di grande interesse, sia dal punto di vista

storiografico sia da quello musicale, per l’alta qualità

della scrittura e la particolarità dello stile, che coniuga

esperienza frottolistica, tradizione laudistica e conoscenza del

contrappunto fiammingo; proprio l’unione di queste componenti

consente una grande varietà nella sonorizzazione delle laude e

permette di spaziare fra sonorità più piene e altre

decisamente cameristiche. La scelta dell’organico per questa

incisione nasce dall’esame delle consuetudini musicali presso la

corte mantovana da un lato e della prassi tenuta dai cantori di laude

delle Scuole Grandi veneziane dall’altro.

Italian sacred music

in the Age of Josquin

Bartolomeo Tromboncino: Laudi e Lamentazioni

Bartolomeo Tromboncino (Verona, c. 1470 - Venice, after 1535) appears

in musicological texts primarily as a composer of secular music. He,

together with his colleague Marchetto Cara, were responsible for a

large number of the frottolas composed between the 15th and the 16th

centuries, under the auspices of Isabella d'Este of Mantua, in whose

service both musicians served for an extensive length of time. The

interest on the part of musicologists in the frottola and the

importance of Tromboncino's work in this genre has resulted in a focus

of study on his secular compositions, considered principally in the

context of stylistic evolution. His sacred output, on the contrary, bas

been almost entirely neglected, a fate which it shares with practically

the entire sacred repertoire by Italian composers active between the

two centuries, for it has been overshadowed by the dominating interest

in the music by Flemish composers. If one excludes the introductions to

modern editions and little else, there are no specific studies

dedicated to the laude of Tromboncino, which are indeed of great

interest, both from an historical and musical standpoint. These works

exhibit a high quality of composition and an individuality of style,

uniting elements of the frottola and the lauda with knowledge of

Flemish counterpoint. It is the very union of these experiences which

allows for their great variety in timbre, ranging from full sonorities

to decisively more intimate ones.

The choice of forces for this recording is based on an examination of

the musical customs at the Mantuan court, on the one hand, and on the

practice of singing laude at the Venetian Scuole Grandi, on the other.

The principal manner of performance of the frottola was with a solo

voice accompanied by a lute, but this does not exclude the possibility

of an entirely vocal performance nor of one with voices and chamber

instruments (recorders, lutes, transverse flutes and even organ). The

resulting sonority would have been well suited to private worship in

the same venues frequented by cantors of laude with lutes or by

frottola singers. Written and iconography documents testifying to the

performance of the polyphonic laude during feasts and processions

usually refer to four singers: a soprano or alto, two tenors with wide

ranges, and a bass, by placing the two different performance practices

side by side, we are able to reconstruct two quite different and even

opposing musical images, which correspond to two musical worlds still

active at the beginning of the sixteenth century: the "bas" music of

the chamber and that of the louder and less refined "hauts" instruments

playing in the open air. In assigning the corresponding typology to

each piece, the determining factor has been the extent to which the

writing style adhered to the model of the frottola. Those compositions

in which the upper voice is distinctly separate from the others, and is

of a declamatory or more melodic character (the Ave Marias, for

example) have been considered more frottola-like, and assigned to the

"bas" instruments. In other works where the two, the marked homophony

or the accentuated rhythms suggest a possible processional performance

or refer to public situations and collective worship, a "outdoor'

sonority bas been chosen. The presence of "hauts" wind instruments,

which throughout the renaissance denoted public office and regalry,

provide breadth and richness to these pieces. In these performances the

group of winds is often antiphonically juxtaposed against the voices.

Cristoforo da Messisburgo cites a rather unusual ensemble of trombone,

two recorders and transverse flute, which we have employed for Salve

Croce. Most of the works seem to have originated as sacred music rather

than being a reworking of celebrated secular compositions. This latter

practice, called contrafactio, was otherwise extremely widespread in

the lauda repertoire, and consisted in applying a sacred text to

frottolas or other secular music. A rare example of this type of piece

is L'oration è sempre bona, extant (perhaps significantly) only

in the Grey codex. A curious example of reversed contrafactum is Sancta

Maria: built upon a plain chant and thus probably sacred in origin, it

had already been published as a strambotto (Me stesso incolpo) in

Petrucci's 4th book of frottolas.

The scarcity of original prints of laude confirm the "minor" role

played by Italian as opposed to Flemish sacred music, and also

underlines the uniqueness of the compositions by Tromboncino, extant

almost exclusively in the publications by Petrucci. It is conceivable

that Petrucci intentionally embarked on a promotional campaign, albeit

short-lived, of Italian sacred music. In any case, it must be stressed

that not even Cara and Tromboncino, who were certainly Italy's most

important musicians, were able to have their own publications of

entirely sacred music. Some of the original pieces can clearly be

defined as frottolas, meaning by this term a particular style of

composition more than a specific literary form. Eterno mio signor is an

example of a "declamatory" frottola with a sort of repeated reciting

note and phrases ending in simple cadences. Arbor victorioso and Ben

sarà crudel e ingrato, on the other hand, exhibit a more active

melodic line and rhythmic importance, In the case of compositions on a

Latin text, the frottola model is replaced by stricter counterpoint, a

more homogeneous texture and an absence of the distinct treatment of

the upper voice in opposition to the others which is so typical of the

genre. The polyphonic construction does not employ the breadth of line

typical of Flemish counterpoint, nor does it strictly develop motifs

and imitation. There pre- dominates instead a great conciseness which

excludes long melismas and shapes the musical phrases to fit the text;

the structure of the phrase is made evident without an attempt to find

a perfect match between words and music. In a few cases, such as the

Ave Maria performed here by 4 voices, there prevails a homophony

punctuated only occasionally by imitative ideas. Conciseness, essential

imitation, and- strong links between music and text: these are the

elements that will prove to be fundamental in the subsequent

development of Italian polyphony in the 16th century.

The lamentationes merit a separate discussion for they differ from the

lauda in length, destination and compositional style. The example heard

here is only a part of the lamentationi printed by Petrucci, but its

unique style justifies the decision to include it on this recording

without the rest of the composition. The Lamentationi were destined to

be performed ad matins of Thursday, Friday ad Saturday of Holy Week.

The long texts divided into three lectiones for each day, concluding

with the words Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum, and

interrupted by Responsories sung in plain chant. Tromboncino sets all

nine lectiones using as a basis the cantus firmus Incipit Lamentatio

Jeremiae Prophetae, which is present in a good many sections of the

composition. Decisively syllabic moments alternate with others in which

a brief contrapuntal idea circulates among the voices for just the

amount of time necessary to finish the phrase. In the presence of the

cantus firmus, the other voices provide a contrapuntal "commentary",

developing what might be called a "deviation": this device both reveals

its frottola origin and simultaneously provides an Italian solution to

sacred counterpoint.

ensemblelesnations.eu

translation Candace Smith