Dorian Recordings DOR-90243

1996

Dorian Recordings DOR-90243

1996

This

is a dramatic recital, using troubadour and other 13th century music to

illustrate some conceptual scenes from the Crusade against the Cathars

(1209-1255). The Cathars were a well-entrenched heretical Christian sect

in the South of France, advocating such things as the spiritual

equality of man & woman. Many people have made some small links

between the Cathars and the emergent troubadour repertory. If one is to

designate their theology as a major motivation for the love poetry of

the troubadours, one must keep well in mind that these poems are

formally similar to classical Latin poems by such writers as Ovid. —

medieval.org

MONTSÉGUR ·

LA TRAGÉDIE CATHARE —

Catalog No. DOR-90243

MONTSÉGUR Alain Bergeron

THE MUSIC

1. Ouverture “Reis Gloriós” [2:40]

Sylvain Bergeron, d'après Guiraut de BORNEIL

EL FIN' AMORS

2. Beata viscera [5:02] PEROTIN

3. La Tierche Estampie Roial [3:50]

4. Quand vey la lauzeta mover [5:28] Bernard de VENTADOUR

5. Loc tems ai / Lo ferm voler [4:02]

Sylvain Bergeron, d'après Raimon de MIRAVAL et Arnaut DANIEL

LA FLÉAU

6. Alle Psalite / Reis Gloriós [1:26]

Sylvain Bergeron d'après Anonyme et Guiraut de BORNEIL

7. Des Oge mais [3:01] ALFONSO X El Sabio

Cantiga 1

8. La Quarte Estampie Royal [2:24]

9. A chantar m'èr [6:39] Condessa de DIA

10. La Septime Estampie Real [2:21]

11. La Seconde Estampie Royal [1:25]

12. C'est la Fins / La Quinte Estampie Real [3:38]

13. Falsedatz et desmezura [5:11]

Sylvain Bergeron, d'après Peire VIDAL; Texte de Peire CARDENAL

CONSOLAMENTUM

14. Benedicite Parcite Nobis [3:12]

Sylvain Bergeron, From the Lyons Ritual/Texte tiré du Rituel Cathare

15. Virgen, madre gloriosa [1:53] ALFONSO X El Sabio

Cantiga 340

16. Jhesu Crist [3:48] Guirault RIQUIER

17. Reis Gloriós [8:25] Alba · Guiraut de BORNEIL

FEUX

18. Veni Sancte Spiritus [5:02]

Sylvain Bergeron, d'après Guillaume d'AMIENS

LA NEF

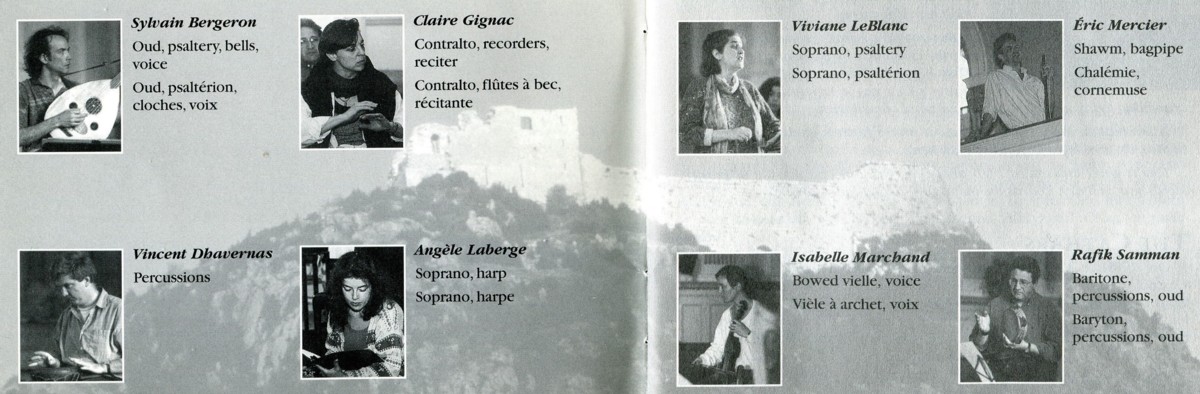

Sylvain Bergeron

Sylvain Bergeron — oud, psaltery, bells, voice

Claire Gignac — contralto, recorders, reciter

Viviane LeBlanc — soprano, psaltery

Éric Mercier — shawm, bagpipe

Vincent Dhavernas — percussion

Angèle Laberge — soprano, harp

Isabelle Marchand — bowed vielle, voice

Rafik Samman — baritone, percussion, oud

LA NEF

The

French word "nef" ("Nave": from the latin navis, 'ship") designated a

large sailing ship of the Middle Ages, a wooden "castle" with a rounded

stern and broad sails that carried crusaders to the Holy land, bringing

back gold for kings. This beautiful and noble name, "nef" or nave in

English, also came to be used for that part of the church reserved for

worship by the laity.

A venturesome world-faring vessel, today's La

Nef is seeking, discovering, exploring, making its ports of call in

distant times and ancient lands. It has gathered a faithful crew:

jugglers, minstrels, actors and jesters. La Nef takes you on an

adventure. In lieu of gold and weapons it carries songs. Sounds heard

over seas of yore, words and melodies collected from foreign shores and

forgotten ports.

* * *

The ensemble La Nef was

created in the spring of 1991. During the last 15 years, all of its

members have been associated with the major ensembles of early music of

Québec. Since its founding, La Nef has presented more than 200

performances and participated in major international series and

festivals including Early Music Now (Milwaukee, 1996), Festival

Internacional Cervantino (Mexico, 1994, 1996), Festival de Flandres

(Belgium, 1993), and Festival de Musica El Hatillo (Venezuela, 1992).

The musical role of La Nef

is to examine the ancient repertoire in its original state, being

flexible and adaptable to restructuring and re-creation. The integration

of a theatrical dimension in its productions throws a new light on the

music. It allows the listener to better perceive the profoundness and

richness of the emotions contained in this music from the past.

Montségur is La Nefs third recording. Music for Joan the Mad [DIS-80128] and The Garden of Earthly Delights [DIS-80135] are available on the Dorian Discovery* label.

LIST OF SOURCES / SOURCES MUSICALES

• Secular music/musique profane

— Anthologie des Troubadours ·

Pierre Bec, ed., (Paris: Bibliothèque médiévale, 1979)

— Poésie lyrique au Moyen-Age (Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1965)

— Medieval Dances ·

Timothy J. McGee (University of Toronto press)

• Religious music

— École de Notre-Dame (Léonin)

— Cantigas de Santa Maria (Alphonse le Sage)

INSTRUMENTS USED IN THIS RECORDING

— Oud:

Oud (Dincer Dalkilic, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1975)

Syrian Oud (unknown builder; modified by Eduard Rusnack, Montreal, 1992)

— Harp: Medieval Harp (Susie Norris, Plainfield, VT, USA, 1985)

— Bowed vielle: 5-string (anonymous, NH, USA, 1984)

— Psaltery: (Claude Guibord, Montreal, 1995)

— Recorders:

Alto, tenor, soprano (Levin Silverstein)

Sopranino (Moeck, 1978)

— Shawn/chalémie: Catalonian/Spanish Shawm (John Hanchett, Dusseldorf, 1987)

— Bagpipe: Veuze Bagpipe (Hervieux & Glet, Redon, Brittany, 1985)

— Bells/cloches: White Chapel Bells (England, 1973)

— Percussions:

Derbouka instruments with metal base

Egyptian Eel Skin Drum

Egyptian day drum

Ocean Drum

Recorded at l'église de la Nativité de la Ste-Viérge, Québec in May 1996

Producer: David H. Walters

Engineers: Craig D. Dory, David H, Walters, Brian C. Peters, Debbie Reynolds

Editor: David H. Walters

Booklet Preparation & Editing: Katherine A. Dory

Graphic Design: Kimberly Smith Company

Executive Producer: Brian M. Levine

Conception and Musical Direction: Sylvain Bergeron

Artistic Direction: Sylvain Bergeron, Claire Gignac,Viviane LeBlanc Historical research: Alain Bergeron

Translation: Ann Rajan assisted by Sybil Murray-Denis, Louise Lafond

Photography: Jean-Louis Gasc, Denis McCready, Craig D. Dory

Acknowledgements: Le Centre National d'Études Cathares, Franc Bardou, Pierre Vellas, Laurent Major, Normand Cazelais, Douglas Kirk

The

concert that helped prepare this recording was given at the Redpath

Hall of McGill University in Montreal, on June 9,1995. It was produced

with the assistance of the Société Radio-Canada (French CBC network).

The

creation of this program was made possible with the support of the

Conseil des Arts et des Lettres du Québec (Programme d'aide aux

Artistes) and the Canada Council (Explorations Program).

℗ © 1996 DORIAN RECORDINGS® a division of The Dorian Group, Ltd.

Long

ago, the Cathars built a castle on the summit o a mountain, and this

castle was also a temple and a refuge. Its walls were cliffs mounted

upon cliffs as strong and as desperate as the hearts o its inhabitants.

In the land of the troubadours , Montségur gave shelter to the most

exacting purity.

But one day, barons came down from the North,

crusaders of Babylon the Catholic. They burnt its flesh and left only

its huge bones of stone, a twisted skeleton still crumbling today under

the sand and wind o centuries.

Assassinated, Montségur survives, a proud fortress gazing, in arrogant silence, on worlds far beyond human ken.

Like

a ghost ensconced high above the Occitan countryside of France

Montségur, solitary, hoards the memory of a long-faded dream.

THE CATHARS

On

10 March 1208, Pope Innocent III called for a crusade. This time it was

not to free the Holy Land but to root out a heresy rampant in the very

heart of Christendom in the land of Raymond VI Count of Toulouse. Rome

had long fulminated against these heretics and the tolerance granted

them by aristocrats in the South of France. On January, Brother Pierre

de Castelnau, the papal legate was assassinated by an officer of Raymond

VI. The pope could not have hoped for a better pretext to strike.

Who

were those people we call the Cathars and against whom was launched a

merciless decades-long crusade? There is no easy answer to this

question. Today, the Cathar phenomenon is still shrouded in mystery and

confusion. War, the Inquisition, and the ravages of time have left us

very few Cathar documents of irrefutable authenticity. What we know

about them is often based on late or hostile sources. Even the

designation Cathar (from the Greek kathoros meaning pure is open

to debate, as those referred to by this name did not themselves use it.

They saw themselves as true Christians - indeed, the only genuinely

"good Christians" - and they looked upon the Roman Catholic church as a

new Babylon dedicated to Satan. On the other hand many of their beliefs

were closely akin to Eastern religions. The absolute opposition of good

and evil, the fundamental duality of mind and matter were directly

inspired by Persian Manicheism. Other elements recall Hinduism and

Buddhism: renouncement of the world, praise of suicide, belief in

reincarnation, and a vegetarian ethic. We know that a Christian form of

Manicheism appeared in the Near East during the first centuries of the

Church. It spread via the Byzantine Empire across the Balkans and the

North of Italy before reaching Languedoc and Catalonia in about the

eleventh century. Catharism took root in the South of France and was

particularly well established in Toulouse and the western parts of

Languedoc, with Beziers, Carcassonne, Albi, and Foix as the main

centers.

What is remarkable about these heretics is that they

lived, apparently with little friction among ordinary Christians and

were even regarded with much sympathy by the population. Cathars

recognized two classes of the faithful: simple believers and Perfects.

Perfects were those who accepted to receive the initiatory sacrament

called the consolamentum. The highest degree of moral rectitude

was demanded of them. They led exemplary and often edifying lives. Their

simplicity, altruism and austerity, which stood in stark contrast to

the corruption and cynicism of so many among the official clergy,

brought them numerous converts.

From a political standpoint, the

vast region of Languedoc - called Occitania from the 19th century on -

then lay under the influence of the counts of Toulouse. The kings of

France, long engaged in process of state centralization saw these counts

as formidable rivals. During the 12th and 13th centuries, Languedoc

culture was considered one of the most sophisticated in all of

Christendom, with the possible exception of Byzance. Toulouse was the

third largest city in Europe. Philosophy was there held in great esteem

as was poetry, and both these forms of expression were strongly

impregnated with Eastern influences. The Arabian world was not very far

away, and Languedoc had seen crusaders returning from Palestine cross

its lands. And just on the other side of the Pyrenees lay the kingdom of

Aragon, one of the main crossroads for the highly complex exchanges

between Islamic and Christian cultures.

It is well known that the

Cathars enjoyed the support of the leading families of the aristocracy

of the South. A high proportion of the Perfects were of noble birth.

Moreover, the Catharist heresy and the courtly art of the Troubadours

flourished in the same soil, although it would be presumptuous to posit a

direct link between the two. Poetic and courtly Fin 'Amors

nurtured new values that prevailed over the crass and violent traditions

of the warlike aristocracy. Essentially opposed to the norms of

Catholic morality, it flouted conventional unions through adultery. At

the heart of Fin 'Amors was the Domna, the beautiful inaccessible

mistress, the object of a passion that could be either erotic or

mystical in nature. Some have sought a parallel between this courtly

celebration of woman and the sexual egalitarism advocated by the

Perfects. Unlike Catholicism which held women as instruments of

temptation used by Satan, the Cathars saw men and women on an equal

footing, because, in their view, both sexes were the victims of Satan.

They condemned marriage and regarded procreation as a crime since it

meant the imprisoning of an innocent soul within a corporal prison

subject to the Devil's law. In practice, however, the moral code of the

Cathars showed them as being open-minded towards adultery with

considerable tolerance for brief amorous adventures among the common

believers. Only the Perfects, who represented a minority, were

constrained to complete chastity.

In the early 13th century,

having tried in vain to dispel the heresy through preaching, the Church

deemed the moment propitious to take more effective action. The Barons

who were summoned would find very conveniently, that their Crusade was

close at hand. Moreover, they were granted the indulgences usually

conferred on those who took up the Cross. The chief star of the Crusade

was Simon IV Count of Montfort, who had won fame in the Holy Land for

his campaign against the Saracens, and who coveted the title of Count of

Toulouse.

While Montfort and his captains waged a campaign of

armed terror, monks mandated by the Pope and his Bishops kept the people

in spiritual bondage. The country was laid waste by armies and the

great machine of the Inquisition judged and condemned thousands of

Cathars to be burned at the stake. Countless stories of untold horrors

described torture and death. Bodies of heretics were exhumed and burned.

Good Christians, deemed suspect, perished in the same manner ...

In

its various stages the Crusade lasted from 1209 to 1255 (Queribus

taken). But the event that was to capture the imagination of future

generations was the siege of Montségur. Built at the summit of an

extremely steep mountain, some 1,200 meters high, this fortress served

as a refuge. Here persecuted heretics found asylum, as did knights and

men of arms being sought by Simon de Montfort's Crusaders. From the very

beginning, the place was also used as a sanctuary by the Catharist

Church and it soon became one of the main centers of resistance for the

occupants. Here at Montségur, an arsenal was secured, plots devised and

preparations made to enable people to go underground.

In May

1243, Hugues des Arcis, Seneschal of Carcassonne, finally established

his armed forces at the foot of Montségur rock. The strategic position

of the castle severely restricted the choice of operations for the

attacking forces. So the siege was a lengthy one. In November, an

expedition of Basque montagnards gave the French a tactical position

enabling catapult attacks. While those under attack could respond in the

same way, their main supply source was soon cut off. By around

Christmas the attackers succeeded in taking the perimeter of the summit

though the Cathars managed to hang on throughout the month of February,

hoping for reinforcements that never arrived. In desperation, they tried

to attack enemy positions but their situation soon became clear. On

March 2, 1244, Montségur surrendered after ten months of siege. Although

about 500 people were then inhabiting the fortress, this included only

about 150 to 200 Perfects. The conditions of surrender were rather

peculiar. A 15-day truce was called. Perfects who renounced their errors

before the Inquisition would be punished but not killed. The rest would

be burned at the stake.

Rather than weakening the Cathars' ranks

it reinforced them. Some twenty men and women chose the supreme rite of

consolamentum, joining the contingent of martyrs. At dawn on March 15,

somewhere between 200 and 225 Perfects (the numbers vary depending on

sources) were brought to the base of a stockade on the slope of the

mountain, where a bonfire was already ablaze.

Following this

event other Cathar fortresses would fall but none with the mythical

significance of Montségur. Later, during the Occitan era the defeated

fortress at Montségur would become the symbol of the South's resistance

to the centralizing influence of the North. Thousands made the

pilgrimage annually to the ruins of Montségur. And it matters little

whether the ruins we view today are truly those of the Cathar fortress

or whether they are the remains of a castle subsequently built by Guy de

Lévis Lord of Mirepoix. Legends endure. And the spirit of the Cathars

lives on among the stone ruins of Montségur.

Virtually

no authentic written document on the Cathars remains. Their musical

practice is unknown to us. However, the Cathar phenomenon flourished in

the same region and during the same era (12th-13th centuries) as the

Troubadour repertoire. Various poetical texts of the Troubadours relate

closely to the Cathar era, expressing the ideas and actions in like

manner. They sing of love, religious or carnal, the higher human values,

nobleness of heart.

Drawing upon basic material which is essentially medieval, La Nef

here offers an original musical realization for voice and early

instruments. The sources have been selected orchestrated and interpreted

in keeping with the concept of opposition. The doctrine of the

Cathars rests on the antagonism between Good and Evil. And history has

retained a dualistic notion of the Albigensian drama: North against

South, invading crusaders against a martyred people. The Church of Rome

against the Perfects or Bonhommes as they were also called).

From

one side loud thunderous sounds of the bagpipes, shawms, percussion.

From the other, the soft instruments (harps, lutes, flutes), women's

voices, the poetry of the Troubadours.

1. Ouverture "Reis Gloriós" • S. Bergeron (after/d'après Guiraut de Bomeil)

Instrumental

The disc begins with an instrumental piece based on the well-known melody Reis Gloriós.

Successively, then in opposition, this overture renders the sounds of

forces present: loud and soft instruments, women's voices. The

magnificent melody, written in Dorian mode, also serves as the program's

leitmotif.

El Fin 'Amors

This

scene depicts the period immediately preceding the Albigensian Crusade.

Evoked here is a way of life in the South of France, which is at once

gentle, refined, hinting of decadence, with a rich and sumptuous but

fragile beauty. The instrumentation calls especially upon the string

instruments: harps, psalteries, vielle, oud.

2. Beata viscera • Perotin

3. La Tierche Estampie Roial • Anonyme /

Instrumental

4. Quand vey la lauzeta mover • Bernard de Ventarour

5. Lonc tems ai / Lo ferm vole • S. Bergeron (d'après Raimon de Miravel et Arnaut Daniel) /

Instrumental

Le Fléau

The

main aspect of this scene is extreme brutality, the ruthless and

decisive character of the devastation wrought by the Crusaders. The

sonorities are loud, piercing, direct. By literally stamping out the

spellbinding sounds of the people of the South, they crush them beneath

their boots.

But this incipient war is no ordinary military

campaign, it is also a Crusade. And from Rome, superimposed on this

unleashing of brute force, is the blessing of the Church. The "Alle Psalite cum Luya"

resounds over the warlike rumblings. The shawm issues its call from the

heights of the ramparts, the percussion pounds the earth, the bagpipe

screams out its retinue of horrors.

6. Alle Psalite / Reis Gloriós • Sylvain Bergeron (d'après Anonyme et Guiraut Borneil)

7. Des Oge mais (Cantiga 1) • Alfonso X el Sabio

8. La Quarte Estampie Royal • Anonyme /

Instrumental

In this Hell of violence, a lone song of love (A chantar m'èr) tries in vain to appease the combatants.

9. A chantar m'èr • Condesa de Dia

10. La Septime Estampie Real • Anonyme /

Instrumental

11. La Seconde Estampie Royal • Anonyme /

Instrumental

12. C'est la Fins / La Quinte Estampie Real • Anonyme /

Instrumental

The denunciatory text of the "sirventes against occupation" (Falsedatz et desmezura)

constitutes the Cathars' response to the invasion. In vain. The

Crusaders launch their final attack. Montségur is taken.

13. Falsedatz et desmezura • Sylvain Bergeron (d'après Peire Vidal; Texte de Peire Cardenal)

Consolamentum

This

scene strikes to the core of the Cathar thinking, its spirituality, its

rites, its secrets. The Perfects of Montségur have had their truce. For

them, all that remains is to pray. On this last night at the fortress,

some request the last rites. The "Benedicite Parcite Nobis" is at

once solemn, hypnotic, mesmerizing. The music of this scene has a sole

purpose: to strengthen faith and lead forward to martyrdom.

14. Benedicite Parcite Nobis • Sylvain Bergeron (From the Lyons Ritual/Texte tiré du Rituel Cathare)

15. Virgen, madre gloriósa (Cantiga 340) • Alfonso X el Sabio

16. Jhesu Crist • Guirault Riquier

Dawn

is nigh. Here the "Reis Gloriós" is offered a final time in a spare but

extremely dramatic version. The text of this "song of daybreak" first

evokes the growing anxiety for the companion's absence, following a

night of love, awaiting reunion which grows later as dawn arrives. Here a

wholly different meaning is expressed.

17. Reis Gloriós (Alba) • Guiraut de Borneil

Feux

The

Perfects walk voluntarily to death. A serene walk, but at once horrible

and terrifying. In assuming their martyrdom, the Perfects knew how to

summon all their energies: the gesture is collective, unanimous,

advances in unison of step and voice. Each person draws strength from

the common flow of movement that carries them on. But these are not

robots walking to unspeakable torture. Doubt, fear, sheer love of life

may still haunt them scarcely a few feet from the stake. The walk itself

is a vast procession to the beyond, suggested by the constant rise of

sonorities to higher registers. It is the passage from the crass

material world to the absolute kingdom of the Spirit. The Perfects are

the chosen ones whom God has called. The Consolamentum which

leads to martyrdom represents the gates they will enter to the promised

Paradise. One by one the sonorities "burn," disappear in the fire,

vanish. This is the end.

18. Veni Sancte Spiritus • S. Bergeron (d'après Guillaume d'Amiens)