medieval.org

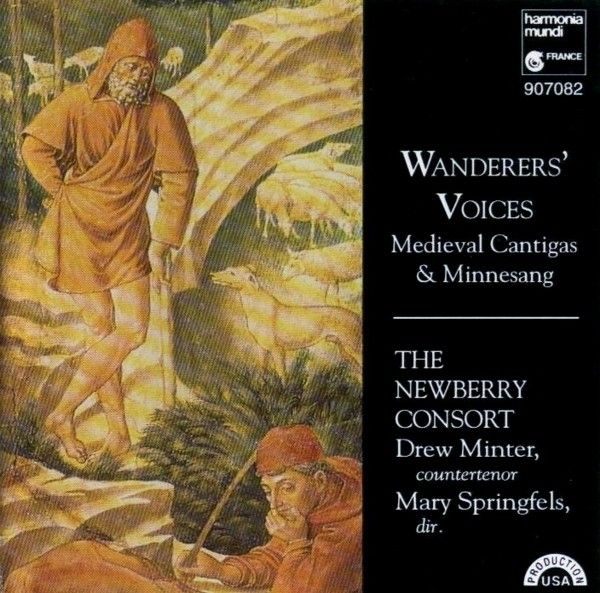

Harmonia Mundi USA 90 7082

1991

Der UNVERZAGTE

1. Der kuninc Rudolp [2:46]

citole, 2 vielles

NEIDHART

2. Sinc an, guldîn huon! [6:14]

voice, rebec, citole

3. Urloup hab' der winder [2:06]

(Pseudo-NEIDHART) instrumental composition based on it

citole, lute

4. Owe dirre nôt! [4:02]

voice, vielle MS

TANNHÄUSER

5. Ich lobe ein wip [3:35]

rebec, vielle MS, citole

Oswald von WOLKENSTEIN

6. Wol auff, gesell [2:52]

citole, 2 vielles

7. Durch Barbarei, Arabia [4:57]

voice, citole, rebec, vielle MS

8. Freu dich, du weltlich creatur [1:23]

rebec, citole, lute

9. Es seusst dort her von orient [12:27]

voice, vielle DD

10. Jocundare plebs fidelis [5:39]

Codex Las Huelgas | 2 vielles

Cantigas de amigo

Martin CÓDAX

voice, vielle DD, lute, citole

11. I. Ondas do mare de Vigo [3:29]

12. II. Mandad'ei comigo [3:41]

13. III. Mia irmana fremosa [1:42]

14. IV. Ai Deus, se sab'ora meu amigo [3:06]

15. V. Quantas sabedes amare amigo [1:25]

16. VI. Eno sagrado en Vigo [1:51]

17. VII. Ai ondas que eu vin veere [2:34]

The Newberry Consort

Mary Springfels

Drew Minter, countertenor

David Douglass, rebec, vielle

Mary Springfels, lute, vielle

Recording: November

18-20, 1991, Skywalker Sound, Nicasio, California

Methuen, Massachusetts

Executive Producer: Robina G. Young

Sessions Producer: Steve Barnett

Recording Engineer: Brad Michel

Editing: Paul F. Witt

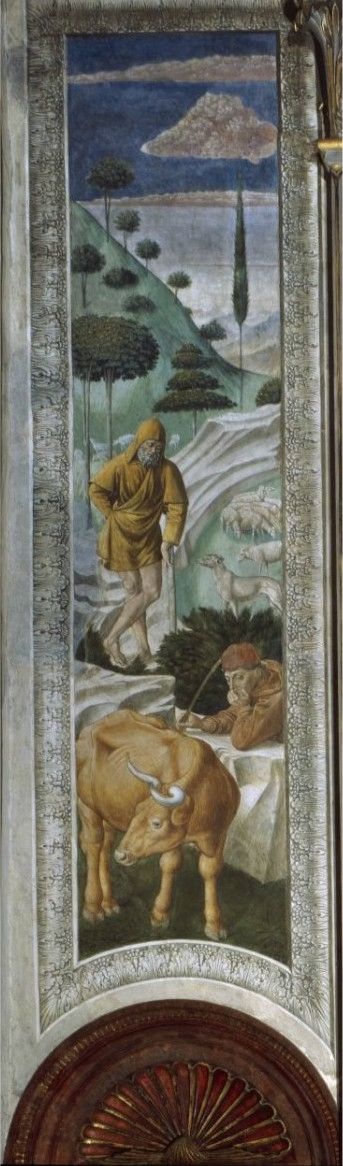

WANDERERS' VOICES

Medieval German love lyric, Minnesang, would never have taken

the form it did were it not for wanderers. In the second half of the

12th century the imperial court under Frederick Barbarossa moved

frequently throughout the territories under his rule, both in Germany

and in Italy. Poets moved too, and it is known that French poets were

present at an important festival organized by Barbarossa in 1184. The

wandering of the court and the wandering of the poets introduced French

and Provençal lyric to members of the imperial court and

inspired them to compose German songs on romance models. These songs,

quite different from previous German lyric, provided in turn the models

for "classical" Minnesang, the remarkable flourishing of German

love lyric in the decades around 1200. Minnesang was written,

usually by aristocratic poets, to be sung before courtly audiences. For

the most part the songs combine a limited number of motives in artful

and often rather abstract commentary on the relationship between the

knightly singer/poet, the noble woman whom he loves, usually in vain,

and the courtly audience to which he addresses his song.

This highly stylized, aristocratic art is the point of reference for

Neidhart, a professional singer and therefore, inevitably, a wanderer.

Neidhart probably began his career in Bavaria, may have gone on a

crusade in 1217, and was active sometime between 1230 and 1246 at the

court of the duke of Austria. Such a court would have had the

sophistication to appreciate what is at stake when Neidhart takes the

conventions of classical Minnesang and transposes them to a

peasant setting. Neidhart still praises his beloved in traditional

terms, but now he is poor and she is a peasant girl. He employs the

traditional vocabulary, but overwhelms it with concrete references to

peasant clothing, dances, and proper names. He still has rivals, but

they are peasant boys, who usually get the better of him. He offers his

beloved his (probably fictitious) home at Reuental — "Valley of

Sorrow." Neidhart, the first Minnesänger whose melodies survive in

any number, was immensely popular and was often imitated in the later

Middle Ages.

While Neidhart's travels seem to have been restricted to southern

Germany and Austria, two centuries later Oswald von Wolkenstein (ca.

1376-1445), a nobleman from South Tirol, travelled throughout Europe

and beyond. He refers to these travels — perhaps with some

exaggeration — at the beginning of "Durch Barbarei, Arabia",

contrasting his previous mobility to the unwelcome isolation in which

he finds himself back home. Whereas Neidhart creates a concrete but

fictional world of peasants, Oswald incorporates specific details from

his own life into his songs: his travels, his successes at court, his

estrangement from his lord. These are combined with a late medieval

genre, a lament on the difficulties of life at home. "Es seusst

dort her von orient" draws on another tradition, that of the Tagelied

or dawn song, which portrays lovers parting at daybreak. Oswald sets

the traditional parting dialogue of the lovers in a world-wide

meteorological context, then concludes each strophe with a highly

condensed, explicitly erotic refrain.

JAMES A. SCHULTZ

Women's songs were composed in abundance throughout Europe in the

Middle Ages. In France, they were called chansons de toile; in

Germany, Frauenlied; in Galicia, cantigas de amigo.

Each national type evolved its own sets of conventions of character,

dramatic situations, and poetic form. We may never know to what extent

any of these large repertoires of lyric verse accurately represented

the voices of real women. In fact, much of this poetry was written for

courtly consumption by men, who presumably performed their own works.

The songs might be better understood as impersonations rather than

authentic depictions of the female point of view.

The Gallego-Portuguese cantigas de amigo constitute the largest and

most attractive genre of medieval women's songs. They owe much of their

form and content to ancient traditional Iberian women's popular poetry.

By the 12th century, the cantigas de amigo, along with their

male-voiced counterparts, the cantigas de amor, were completely

a product of the high court culture. Their seeming artlessness was very

carefully cultivated.

Over five hundred cantigas de amigo survive today, but only

six, written by the mid-13th-century poet Martin Codax, still possess

their music. A single, damaged sheet containing seven poems and six

melodies was discovered in 1914 in the binding of a later volume. This

somewhat enigmatic treasure is now in the collection of the Morgan

Library in New York. Even though two of the poems in the Morgan

manuscript seem to have been added at a slightly later date, for a

variety of stylistic reasons, Codax' cantigas are still

generally thought to be a cycle, the earliest song cycle known to

Western music.

Given the restricted number of words in the cycle, Codax was able to

convey an impressive amount of narrative information. True to the

traditions of the cantiga form, the singer is alone. Her absent

lover is away on a sea voyage, but she has received word that he will

soon return. She is overjoyed but anxious. She rejoices that he is safe

and boasts that he is a favorite of the king. She calls out to her

mother, who seems to be an ally, and invites her sister to share her

seaside watch with her. She has chosen the holy shrine at Vigo as her

trysting place. She feels profoundly alone, free even of chaperones or

spies. She sings of a time when her lover will swim in the sea with

her. She dances for her absent lover in the shrine, describing herself

as a woman who has known no man, except her friend. She concludes her

solitary vigil with a final invocation to the waves.

Much of the effect of this elegant series of little strophic songs is

in its build-up of sensuous and dramatic detail, word by word. The Cantigas

de amigo of Martin Codax are in many ways a quintessential medieval

artifact. Every element is derivative of some ancient model (which

might even include The Song of Songs): poetic originality as we

appreciate the concept had very little meaning for the medieval artist

or his audience. Nevertheless, this compilation of well-known motifs

manages always to be fresh, immediate, and moving, an exquisite

expression of longing.

MARY SPRINGFELS