medieval.org

Harmonia Mundi USA 90 7226

1997

01 - Suite of Branles [3:09]

02 - Johannes STOKHEM. Je suis d'Alemagne [1:39]

tenor

03 - Basse dance. Marchez là dureau [1:06]

04 - Puis qu'aultrement - Marchez là dureau [2:32]

05 - Antoine de FÉVIN. Soubz les branches - En La rousée de May [4:19]

tenor, countertenor, baritone

06 - Antoine de FÉVIN. Il fait bon aimer l'oyselet [4:30]

countertenor

07 - Bon vin [2:45]

tenor, countertenor, baritone

08 - La Gelosia [1:38]

09 - Petit vriens [1:50]

10 - La danse de Cleves [2:38]

arr. Ross W. Duffin

11 - En douleur et tristesse [6:11]

12 - La belle se siet [2:03]

countertenor

13 - En amours n'a sinon bien [3:33]

tenor

14 - My, my [2:51]

15 - J'aimeray mon amy [1:35]

16 - Belles tenés moy - La triquotée [0:51]

17 - Rolet ara la tricoton - Maistre Piere - La tricotée [1:14]

countertenor

18 - Amours m'ont fait [3:21]

tenor

19 - Petit fleur [1:25]

20 - Faisons bonne chere [1:05]

21 - Reveillez vous, Piccars [3:28]

tenor, countertenor

22 - L'autrier quant je chevauchoys [3:33]

countertenor

23 - Clément MAROT, Thoinot ARBEAU. Jouissance vous donneray [2:11]

24 - Quant je suis seullecte [4:02]

tenor, countertenor

25 - Héllas! mon cueur n'est pas à moy [4:10]

countertenor

26 - Antoine de FÉVIN. Faulte d'argent [2:45]

tenor

27 - Antoine BUSNOIS, Adrian WILLAERT. Vostre beauté - Vous marchez du bout pié [1:11]

tenor, countertenor

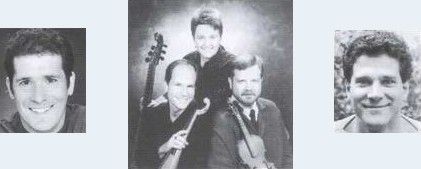

The Newberry Consort

Mary Springfels

Mary Springfels, vielle, rebec, Renaissance viola da gamba

David Douglass, vielle and rebec

William Hite, tenor

Drew Minter, countertenor and harp

Tom Zajac, baritone, harp, Renaissance recorders and flutes,

hurdy-gurdy, bagpipes, percussion

INSTRUMENTS AND THEIR MAKERS

Tom Zajac plays:

Bagpipe, Fritz Heller, 1985

Hurdy-gurdy, Lyn Elder, 1980

Hurdy-gurdy, George Kelischek, 1978

Three-hole pipe, Thomas Prescott

Tabor drum and tambourine, Ben Harms, 1990

Portuguese folk tambourine

Renaissance flute in C and Renaissance alto recorder, Philip Levin 1988

Renaissance flute in D, Ron Leszewski, 1978

Renaissance tenor recorder, Thomas Prescott, 1996

Tenor sackbut, Frank Tomes, 1989

Harp, Lynn Lewandowski, 1994

Mary Springfels plays:

15th century lute, Lawrence Brown, 1978

Vielle, Lynn Elder, 1980

Renaissance viola da gamba, Helmut Muenzberger, 1988

(thanks to Alice Robbins for the loan of this instrument)

David Douglass plays:

Vielle, Eugen Sprenger, 1965

Rebec, Arthur Douglass, 1975

Rebec, Lyn Elder, 1980

Drew Minter plays:

Harp, Lynn Lewandowski, 1981

Recorded November

9-11, 1997, Methuen Memorial Music Hall, Inc.,

Methuen, Massachusetts

Executive Producer: Robina G. Young

Sessions Producer: David Douglass

Recording Engineer: Brad Michel

VILLON to RABELAIS

16th Century Music

of the Streets. Theatres, and Courts

The lives of François Villon (1431—?/1463) and

François Rabelais (1490?/1494-1553) circumscribe a luminous

period in French literature, and their writings, while quite different

from one another formally, lean toward the personal and burlesque, full

of slang and local color. This picturesque quality arises in part from

their unofficial status as writers for neither managed to garner noble

patronage. Villon lived by his wits in the Paris underworld, amassing a

substantial criminal record of theft and even manslaughter that nearly

brought him to the gallows before he was exiled from Paris. Rabelais

played the role of secular cleric to better gain than Villon, bur he

too suffered eventual exile when the Sorbonne censured his Gargantua

and Pantagruel for their ribald subversion of authority. Both writers,

then, reported on French life from unique perspectives, Villon

complaining about city life and Rabelais poking fun a the monastics and

scholastics he knew so well.

In the same spirit as Villon and Rabelais, contemporary composers such

as Loyset Compère, Antoine Busnoys, and Antoine de Févin

took up the idioms of popular urban songs in their written

compositions, spicing up the polyphonic chansons they wrote at court

with texts and tunes borrowed from le menu peuple. The

repertory which resulted combined lofty verse extolling unrequited

amour courtois with popularesque poetry that promoted sexual adventure

in chansons written in both high and low musical styles.

Traditionalists among court composers continued to aim high, choosing

poems written in one of the fixed forms of rondeau, ballade, or

virelai that had governed lyric production since Machaut.

Equally fixed were the subjects proper to courtly verse, which reworked

themes of hopeless desire for a distant or cruel mistress, or, less

often, for a male lover, as in "Amours m'ont fait." Perhaps because

15th century rhetoric so carefully prescribed the forms and topics of

poetry, word play became paramount, and highly-coded language typifies

the school of the grands rhétoriqueurs who furnished

polyphonists with so much chanson verse. "En douleur et tristesse"

typifies the courtly art with its strophes of loving servitude and rich

four-part polyphony. "Quand je suis seullecte" is a rondeau

that beautifully alludes to this highest style both formally (fixed

form poetry) and musically (relatively complex polyphony) at the same

time as the stanzas undercut the "purer" sentiment of the refrain with

phallic references to a distaff and the wakefulness of sexual

irritation.

Combinative chansons with multiple texts take the admixture of high and

low to a new level, playing on the conceit of a love-death that

exhausts sexual desire. This rich polyphony of texts—some as

raunchy as the explicit superius of "Soubz les branches/En la

rousée de May/Jolis mois de May"— was matched with

exquisite counterpoint. Yet the stunning musical effect of songs like

these in no way negates their weird mix of courtly and carnivalesque

lyrics. Rather, they point to a growing taste at the court of Louis XII

for verse with slighter tone set polyphonically.

One important source of friskier songs was the Parisian public theater.

"Faulte d'argent," "La triquotée," and "Je suis d'Alemagne"

would all have been heard there, performed by town minstrels and

play-acting societies like the Enfants sans soucis, of which

Clément Marot, the author of "Jouissance vous donneray," was a

member. Sometimes, however, the grands rhétoriqueurs

penned verse in the low style, though rarely as smutty as the chansons

rustiques from the theater. Many of the monophonic chansons

included here originated at the court and are drawn from a sumptuous

manuscript of faux-rustic songs for gentle pleasure. Finally, popular

chansons were often reworked as basse danses. The basse

danse was the most intricate of the social dances at court,

requiring a rhythmic surety of the dancers unknown in simpler dances

like the bransle, which sat at the bottom of the social scale.

In dance reworkings, the song tune becomes a stretched-out tenor line

above which new melodies are improvised, a technique audible in the basse

danse "Marchez là dureau" where the rocking minor thirds of

the monophonic song can be heard quite clearly in the tenor. Other

instrumental pieces, such as the set beginning with "La Gelosia," were

improvised over chanson melodies that proceeded in tempo in the tenor.

Dances themselves were organized into suites cast in a sort of rhythmic

acceleration like the bransles offered here.

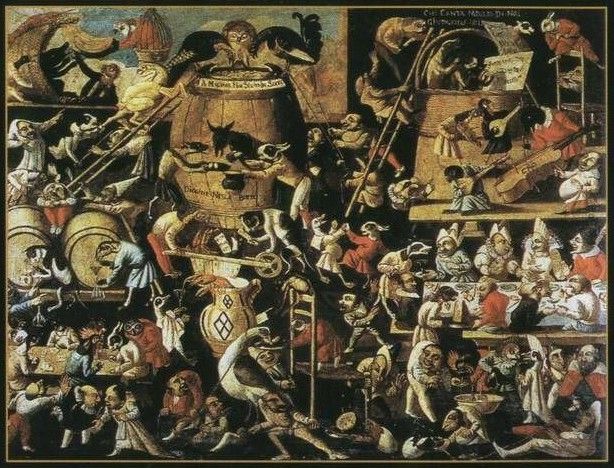

If much of this music sounds intimate and even diminutive, one

gargantuan feature is its wealth of instruments. Rabelais details

Gargantua's education with the humanists where he read the classics and

learned rhetorical skills. After dinner, Gargantua played cards, dice,

and music in order to develop an affection for arithmetic and the

mathematical sciences, which aided digestion:

Après se esbaudissoient à chanter musicalement à

quatre et cinq parties, ou sus un theme, à plaisir de gorge. Au

reguard des instrumens de musicque, il aprint jouer du luc, de

l'espinette, de la harpe, de la flutte de Alemant et à neuf

trouz, de la viole, et de la sacqueboutte. Gargantua

(Afterwards they would rejoice in singing musically in four or five

parts, or on a theme, at the throat's pleasure. Regarding musical

instruments, he learned to play the lute, harpsichord, harp, the German

flute [traverso] and the nine-holed flute [recorder], the viol, and the

sackbut.) Gargantua

To the Rabelaisian instrumentarium, this recording adds the vielle (an

instrument for blind beggars, according to one 16th century source),

the rebec (for minstrels), the hurdy-gurdy, and two kinds of bagpipes,

besting even Gargantua himself.