medieval.org

Christophorus CHR 77279

mayo de 2005

Evangelische Kirche, Gönningen

medieval.org

Christophorus CHR 77279

mayo de 2005

Evangelische Kirche, Gönningen

01 - Invocatio. Wola drúhtin min · Invocatio

scriptoris ad Deum (lib.I, cap.II) [1:30]

02 - Invitatorium & Ps 94(95). Præoccupemus

faciem Domini [9:19]

03 - Hymnus. Vox clara ecce intonat · Hymnus im

Advent [2:04]

04 - Lectio I. Thiz sint búah frono · Liber

generationis Jesu Christi NH David (lib.I, cap.III) [3:01]

05 - Responsorium. Aspiciens a longe

· Vigil zum 1. Advent [7:31]

06 - Lectio II. Ward áfter thiu irscrítan sár

· Missus est Gabrihel Angelus (lib.I, cap.V) [2:51]

07 - Responsorium. Sancta et

immaculata virginitas · Vigil zum Weihnachtsfest

[2:33]

08 - Responsorium. Suscipe verbum Virgo Maria ·

Vigil zum 2. Advent [2:50]

09 - Lectio III. Fûar tho sancta Mária

· Exurgens autem Maria abiit in montana (lib.I, cap.VI)

Thó sprah sancta Mária · De cantico

sanctæ Mariæ (lib.I, cap.VII) [3:36]

10 - Responsorium. Beatam me dicent omnes generationes ·

Vigil zum Fest der Heimsuchung Mariæ [2:29]

11 - Responsorium. Ecce apparebit Dominus · Vigil

zum 3. Advent [2:42]

12 - Hymnus. Veni Redemptor gentium · Hymnus im

Advent [3:10]

13 - Lectio IV. Wúntar ward tho máraz ·

Exiit edictum a cæsare augusto (lib.I, cap.XI) [1:41]

14 - Responsorium. O Magnum

mysterium · Vigil zum Weihnachtsfest [3:29]

15 - Responsorium. Beata Dei Genitrix · Vigil zum

Weihnachtsfest [2:05]

16 - Lectio V. Tho wárun thar in lánte ·

Et pastores erant in regione eadem (lib.I, cap.XII) [2:17]

17 - Responsorium. Hodie nobis cœlorum Rex · Vigil

zum Weihnachtsfest [3:41]

18 - Responsorium. Verbum caro factum est · Vigil zum

Weihnachtsfest [4:48]

19 - Lectio VI. Thar was ein mán alter · De

obviatione et benedictione Symeonis (lib.I, cap.XV) [2:15]

20 - Responsorium. Adorna thalamum tuum Sion · Vigil zum

Fest Darstellung des Herrn [4:49]

21 - Oratio. Giwérdo uns geban drúhtin ·

Oratio (lib.V, cap.XXIV) [2:58]

22 - Antiphona. Alma Redemptoris

mater [1:54]

ENSEMBLE OFFICIUM

Wilfried Rombach

Marion Bücher-Herbst & Laila Finvik-Pettersen (Soli)

Miriam Barth, Sibylle Henn, Alena Leja, Christine Rombach

Jörg Rieger & Steffen Doberauer (Rezitationen), Wilfried

Rombach (Soli)

Florian Schmidt, Daniel Herrscher, Jens-Martin Ludwig

Marc Lewon, Uri Smilansky, Elizabeth Rumsey (Fideln)

Leitung / Direction:

Aufnahme: 13.-14.6.2005, Ev. Kirche Gonningen

Tonmeister & Schnitt: Andreas Priemer

Toningenieur: Matthias Neumann

Produzent: Gunilla Gustayson

OTFRID OF WEISSENBURG (c 800 - 870): LIBER EVANGELIORUM

Verse and Music from the time of Charlemagne

by Wilfried Rombach and Marc Lewon

One of the most significant artistic achievements in Carolingian

literature is the Liber evangeliorum by Otfrid of

Weissenburg, a monk (c. 800-870) who lived and worked at the Abbey

of Saint Peter and Saint Paul at Weissenburg (French: Wissembourg) in

Lower Alsace. Otfrid had been a pupil at the renowned Fulda Abbey

School, a centre of religious and spiritual life during the Carolingian

era. The school owed its new prosperity and reputation to the abbot,

Hrabanus Maurus (784-856), a man of learning whose pupils included

numerous scholars and abbots of the Abbey of St. Gallen, as well as

Otfrid of Weissenburg. Otfrid wrote his Liber evangeliorum, his

most important work, between 863 and 871. It is his transposition of

the Bible stories about the life of Jesus from the Latin of the gospels

into the South Franconian dialect of Old High German, a gospel harmony

in which the four gospels are distilled into one narrative. The entire

work is in verse - 7,104 long lines divided into five books comprising

a total of 140 chapters. In the 9th century it was highly unusual for

vernacular literature to be written down. The close association between

Latin and the written word, which had existed in western Europe since

the days of antiquity, meant that applying Latin characters to

vernacular language was no easy feat. There was, after all, no system

of grammar and no standardised spelling. The task of writing a whole

book in this way was pioneering work, and it resulted in the earliest

substantial text in Old High German still in existence.

We see from Otfrid's opening remarks and dedications at the start of

the work that he was aware of the novelty and vulnerability of his

project. Whilst admitting that the Franconian language is still

"boorish" and does not follow the rules of (Latin) grammar, he

nevertheless recognises its hidden potential and calls for his language

to be accorded the same respect (as Latin):

It [Franconian] has not yet been used for verse in the fashion

aforesaid, it is true, and it does not yet obey the rules; however, it

too conforms to a pattern, in its agreeable simplicity. Strive with the

utmost zeal, therefore, to make it sound beautiful, so that God's

command may resound wonderfully within it [...]

Despite Otfrid's assertion, contemporary vernacular verse did already

exist, although it was not based on Latin grammar or classical

versification and it was not written down. It seems that it was this

kind of heroic poetry and shorter songs in the vernacular that prompted

Otfrid to undertake his gospel harmony:

When once the ears of splendid men were afflicted by worthless nonsense

and vulgar singing by laymen disturbed their pious frame of mind, a

number of my fellow brothers asked me [...] to write a gospel harmony

in the vernacular, so that the rendition of this holy text might, in

some small way, restrain the enjoyment of worldly songs [...]

Otfrid views the Franks, and thus their verse, as successors to the

glorious ancient civilisations and their literature. His aim is to make

the holy texts accessible to a broader section of society, to those

ignorant of Latin, and at the same time to help the Franks establish a

literature of their own - the only accomplishment in which they

remained, in his opinion, inferior to the ancient civilisations. He

therefore "invents" a new form for his work, combining the medium of

traditional Germanic poetry with the more even metres of Latin verse

and the stylistic device of the end rhyme. The use of the end rhyme as

a defining structure for verse was something new - it had been known as

a rhetorical effect since antiquity, but it was not used as the

systematically recurring structure that we have now come to regard as

almost the definition of poetry. Otfrid's end rhymes are often,

admittedly, merely assonances - lines of verse whose endings sound

similar - and they are free of the constraints of strict rhyme, which

eventually became the model during the High Middle Ages. In Germanic

oral literature, the alliterative long line was the norm, and Otfrid

now crowns this with the end rhyme - to distinguish his work formally,

perhaps, from secular, vernacular verse, to make it "better". He

retains the long verse line structure, however, and the traditional,

alliterative stave rhyme also continues to come through in many

passages, often the more poetic ones, such as the chapter which

includes the Annunciation.

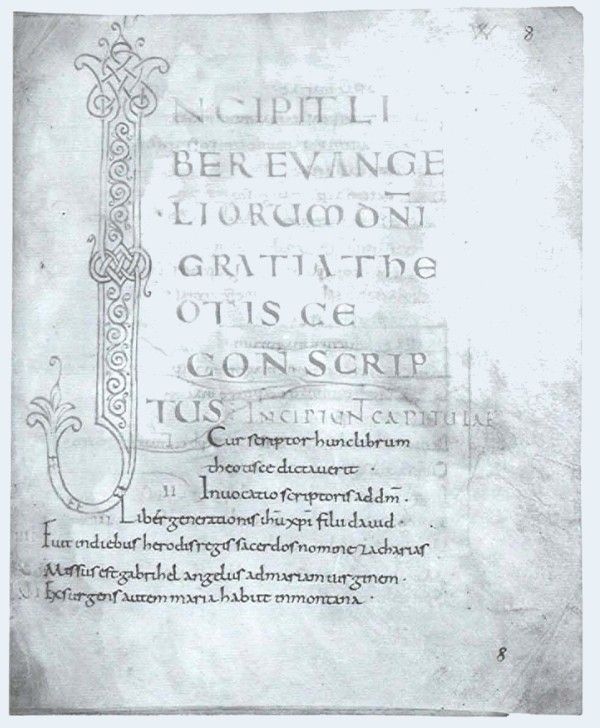

From Weissenburg Abbey, Otfrid cultivated close contacts with important

figures at the famous Abbey of St. Gallen all his life, and he

dedicated the Liber evangeliorum to two St. Gallen friends,

Hartmut and Werinbert. It is possible that the copy preserved today in

Heidelberg University Library (Cod.Pal.lat.52) is the manuscript

originally found at the Abbey of St. Gallen. This hypothesis is

supported by the existence of neume notations above some of the verses,

the same symbols used by the scribes at St. Gallen for notating

Gregorian chant. These neumes provide unique information about the

articulation and interpretation of the melodies. We can therefore

assume that not only were extensive sections of Otfrid's verse sung, as

was customary with medieval verse, but that the Liber evangeliorum

was also probably used for text readings during the liturgy.

On this basis, ensemble officium has attempted to

reconstruct the musical setting of the Liber evangeliorum texts,

bearing in mind the variety of possibilities as to how the recitations

might have sounded. On this recording liturgical models of recitation

and reading are used for the majority of the readings. Passages of text

which are particularly fine, however, receive an embellished melodic

treatment based on the reconstruction by Ewald Jammers, while

incorporating some contextual changes and text-based adaptations. Ewald

Jammers first attempted to reconstruct the melodies from the neume

symbols in the Heidelberg manuscript in 1957.

This recording, the first, aims to place the Liber evangeliorum

in a liturgical context, to show how it might have been used and to

create an exciting relationship between the two. Otfrid's verse is

complemented by Gregorian chant - sung from a liturgical manuscript

written around 1000 by Hartker, a recluse who had himself immured in

his cell at the Abbey of St. Gallen for thirty years. The Antiphonarium

officii (Cod.Sang.390/391), which was written there, is one of the

most important musical manuscripts of the Middle Ages. His script, his

illuminations and his neume notation all show astonishingly high

standards of craftsmanship, musicality and discipline. The music in the

two manuscript volumes is not written in the notation familiar to us

today but uses the same symbols above the liturgical text as those

found in the Otfrid manuscript in Heidelberg. Although these neumes

only give a rough indication of the melodic line, they give its agogic

accentuation all the more clarity. The very elaborate night vigil

responsories in the Antiphonarium officii tend to be based on

Old Testament texts and provide a commentary on the New Testament

message of the Otfrid readings. The result is a programmatic setting

closely resembling the vigils at an abbey.

We begin with the Invocatio [1], the author's plea for the

ability to portray the life of Christ truthfully and with humility.

Tellingly, Otfrid borrows his formulation from the opening part of the

liturgy of the hours, which is traditionally introduced by the

twice-repeated invocation "O Lord, open thou my lips" (Psalm 51,15).

The following invitatory Præoccupemus faciem [2] consists

of an antiphon and the solemn recitation of Psalm 95, performed here by

two female vocalists in alternation. Since time immemorial, this too

has been a fixed part of the opening to the morning liturgy of the

hours. Like the preceding invitatory, the hymn Vox clara ecce

intonat [3], a first high point in the introduction to lauds, also

comes from the Advent vigil liturgy.

The readings selected for this recording are taken exclusively from the

first book of the Liber evangeliorum, which is devoted to the

Christmas story. The narrative is based on Matthew 1,1-17 and begins

with the Liber generationis [4], a rendition of the genealogy

of Jesus from Adam through Noah, Abraham and David to Mary (slightly

abbreviated for this recording). This text is articulated in "tonus

lectionum", a style of intonation still used in the delivery of

liturgical readings today. The assembled monks would answer with Aspiciens

a longe [5], the first responsory in the Advent Sunday vigil and

thus the first freely written and composed canticle of the new Church

year, whose high level of artistry and unusual length reflected its

status in the calendar.

The next reading, Missus est Gabrihel angelus [6], is dedicated

to the well-known prayer "Ave Maria". Like a medieval painter, Otfrid

describes every detail of the encounter between Mary and the angel

Gabriel. Musicological research into Otfrid of Weissenburg's gospel

harmony centres on this fifth chapter of the first book. The presence

of neumes, mentioned earlier, above verses 3 and 4 in the Heidelberg

manuscript suggests that the Liber evangeliorum was also sung. A

possible explanation for the autonomous musical arrangement indicated

here by the neumes is that this especially poetic chapter may have been

written as a separate "Canticum" before the Gospel Book was completed.

In his analysis, Ewald Jammers believes he can detect the recitation

tone "accentus Moguntinus", which was in use in the Archdiocese of

Mainz (including Weissenburg Abbey) during the Middle Ages. We have

therefore set this whole reading to that melody.

The reading Exsurgens autem Maria [9] draws together two

chapters (I,6 and I,7) of the Gospel Book. lt describes the scene in

which Mary visits her cousin, Elisabeth, and is transported by emotion

to sing the visionary Magnificat. Because the text of this canticle is

one of the most important in the liturgy and has inspired great

compositions throughout history, it is given special treatment on this

recording, though with no claim to authenticity. The responsory which

follows, Mariæ Beatam me dicent [10], is also based on

the text of the Magnificat and is taken from the vigil of the

Visitation of Mary.

The well-known Advent hymn Veni redemptor gentium [12] marks

the beginning of the second part of the recording and of the Christmas

story itself. In keeping with the practice of solemnly reading the

Christmas gospel on Christmas Eve, the reading Exiit edictum a

Cæsare Augusto [13] is recited in the sung gospel tone. It is

followed by what is surely the most fervent Christmas song of the

Middle Ages, the responsory O magnum mysterium [14]. The

reading Et pastores erant in regione eadem [16] is an almost

unsurpassably vivid description of the scene in which the angel appears

to the shepherds in the field, bringing news of the Saviour's birth.

Although very little is known about the use of instruments in church,

medieval writings are littered with prohibitions on the use of

instruments in the liturgy. The human voice was the ideal in liturgical

music, the only "instrument' worthy of praising God. However, the

constant repetition of such bans might also suggest that instruments

were in fact widely used in religious music. We decided in favour of

using instruments for the purely acoustic medium of a CD on aesthetic

grounds. This recording features three fidels recreated from medieval

representations: sculptures in Chartres Cathedral dating from the end

of the 12th century and an image in a Bible dating from the middle of

the 12tha century (London, British Library, Harleian Ms. 2804).

The most striking feature of the Christmas vigil responsory Verbum

caro factus est [18] is its jubilus, a melodic embellishment of the

final syllable. This form is rather atypical of the liturgy of the

canticles of the hours, but it doubtless symbolises the infinite joy

over Christ's incarnation and the beginning of the salvation of God's

peopie. The scene described in the reading De obviatione et

benedictione Symeonis [19] once marked the end of the Christmas

season. On a visit to the temple, the aged Simeon praises God for

fulfilling his promise about the Messiah and prophesies the Passion of

Christ. His hymn of praise, the "Nunc dimittis", is one of the most

important prayers in the liturgy. It is used daily by priests and monks

in the liturgy of the hours at compline. The event is also celebrated

by the present-day Church on 2 February under the name of "The

Presentation of the Lord in the Temple" (previously Candlemas). The

final Oratio [21], which is taken from the fifth book (V,24),

and marks the end of the life and work of Jesus, is followed by the

Marian antiphon Alma redemptoris mater [22]. As the concluding

canticle, this traditionally ends the compline service and brings the

monks' day at the abbey to a close.

translation: Debbie Hogg