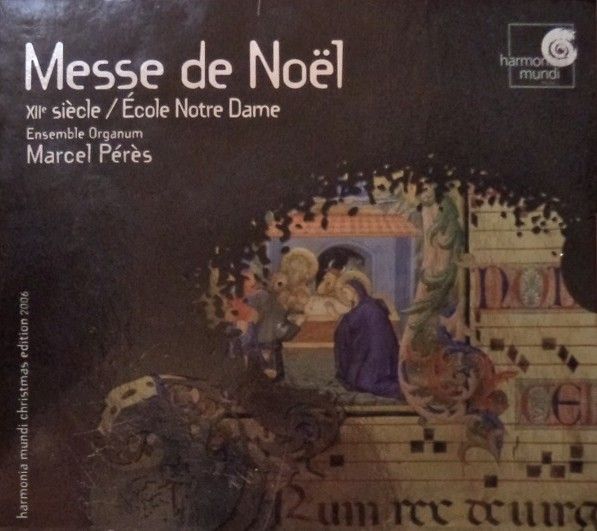

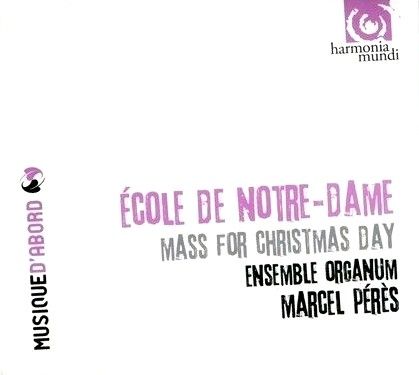

LÉONIN | Messe du Jour de Noël

École de Notre Dame / Ensemble Organum

medieval.org

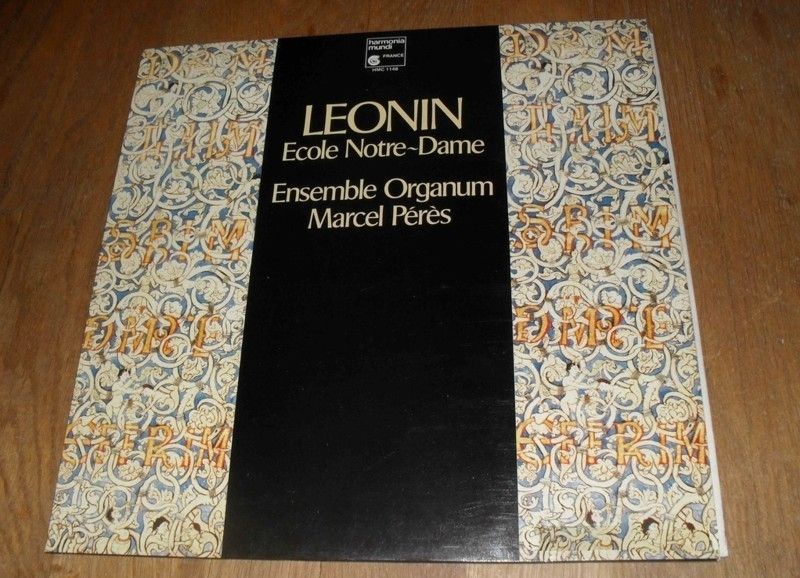

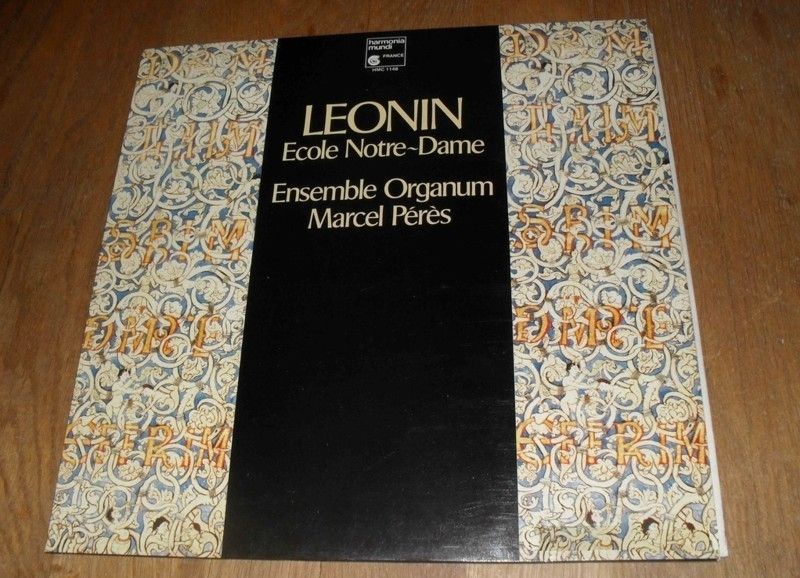

harmonia mundi HMC 1148 · 1985 LP

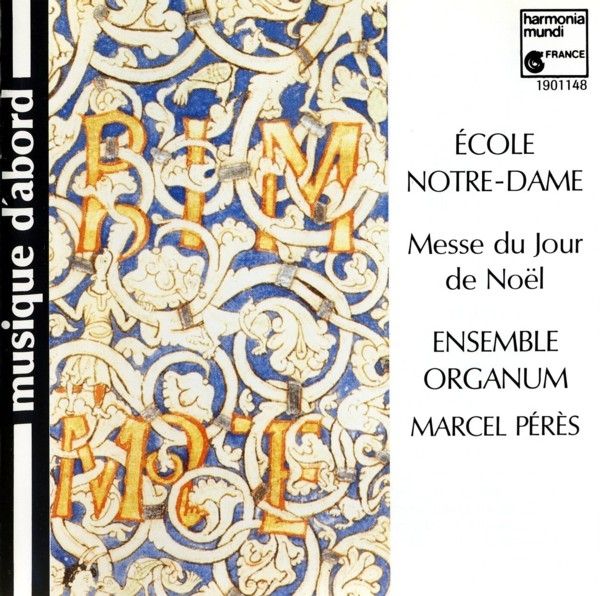

harmonia mundi HMC 190 1148 · 1985 CD

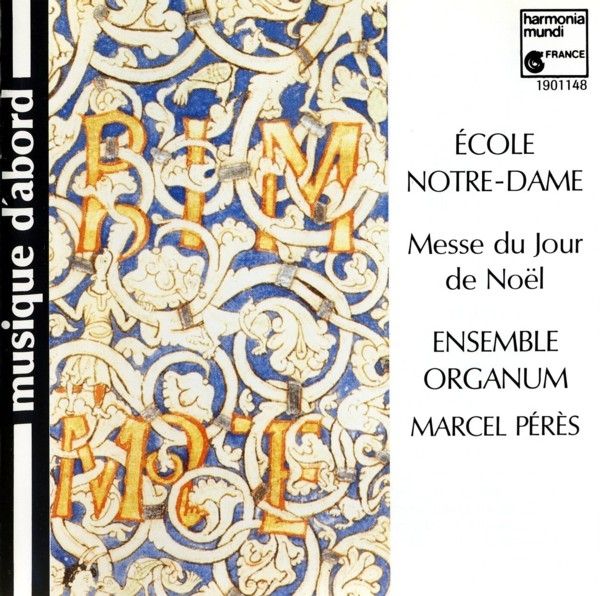

harmonia mundi “musique d'abord” HMA 190 1148 · 1989

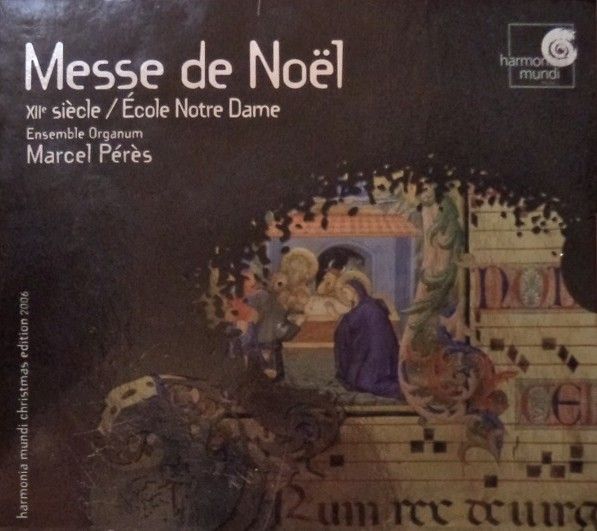

harmonia mundi “Christmas Edition” HMX 190 1148 · 2006 (Christmas edition)

harmonia mundi HMA 195 1148 · 2011 — ‘Mass for Christmas Day’

1. Introït tropé. Puer natus est [6:02]

Provins - Bibl. Mun. 12 (24), fol. 16 17

2. Kyrie [2:14]

Paris - B.N. Lat. 1112, Fol. 257 r.

3. Graduel. Viderunt omnes [7:47]

organum — contre-ténor, ténor

organum: Wolfenbüttel Helmst. 628, Fol. 21 r. 21v.

monodie: Paris B.N. Lat. 111, Fol. 20

4. Alleluia. Dies sanctificatus [7:51]

organum — ténor, baryton I

monodie: Paris B.N. Lat. 111

organum: Wolf. Fol. 21 v., Fol. 22 v

5. Evangile. Prologue de St-Jean [2:52]

ténor

6. Offertoire. Tui sunt coeli [8:23]

tutti et soli: baryton I, contre-ténor, ténor

Offertoires neumé - Solesmes / 1978 / R. Fischer

7. Préface. Dominus vobiscum [1:55]

ténor —

Wolf. Helmst. 628

8. Sanctus [4:14]

organum — ténor, contre-ténor, baryton I

Wolf. Helmst. 628

9. Agnus Dei [0:55]

tutti —

Paris - B.N. Lat. 1112, Fol. 259

10. Communion. Viderunt omnes – Ps 97 [3:57]

tutti —

Graduel Triplex Solesmes 1979 / R. Fischer / M.C. Billecocq

11. Ite missa est - Deo gratias [4:00]

organum - baryton II, ténor, tutti

Florence - Bibl. Laurenziuna, Pluteo 29- 1/Fol. 39v.

Ensemble Organum

Marcel Pérès

Gérard Lesne, contre-ténor

Josep Benet, ténor

Josep Cabré, baryton I

Philippe Balloy, baryton II

harmonia mundi s.a., Mas de Vert, 13200 Arles ℗ 1985, CD 1989

Enregistrement juillet 1984

Prise de son Jean-François Pontefract

Traductions G. Lobrichon, H. Perz, D. Yeld

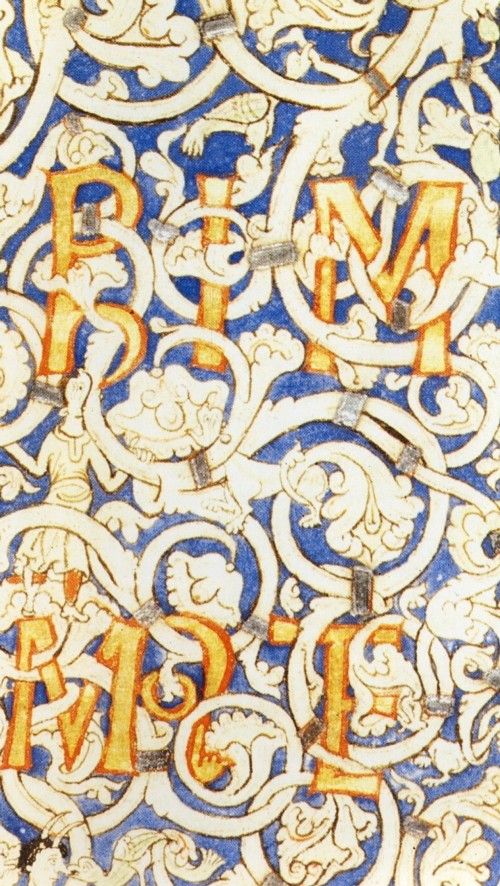

Illustration : St-Amand, Bible latine, tapis signé du moine Savalo

Cliché Giraudon

Maquette Relations

English liner notes

Dès

le milieu du XIIe siècle, l'École de chant de Paris rayonne dans

l'univers de la chrétienté occidentale par la qualité de ses chanteurs

et surtout par l'art avec lequel ils improvisaient les organums. Le

chant polyphonique était essentiellement un art d'improvisation, mais

avec le sens que le mot improviser possède dans toute société de

tradition orale. Il s'agissait en fait d'un art de la centonisation.

Telle formule, liée à un mouvement particulier, était enchaînée à une

autre, et ainsi de suite, jusqu'à ce que la mosaïque ainsi constituée

forme un tout harmonieux dans ses proportions.

Certains

historiens de la musique, par manie de la classification, ont découpé le

début de l'histoire de la polyphonie occidentale en trois époques :

— La période du contrepoint parallèle, IXe-Xe s. (certains auteurs parlent d'hétérophonie),

— La période du contrepoint en mouvement contraire, XIe siècle.

— La période du contrepoint fleuri, XIIe siècle.

La

réalité semble plus complexe. Bien que le premier témoignage du

mouvement parallèle soit de la fin du IXe siècle, cette pratique est

encore attestée au XVIe siècle. Encore de nos jours, certaines

polyphonies populaires en portent les traces. Le mouvement contraire est

connu à la fin du Xe siècle, mais Jean Scot Erigène semble en parler au

milieu du IXe siècle. Il sera lui aussi pratiqué, dans certains

endroits, jusqu'au XVIe siècle. Quand au contrepoint fleuri, le premier

témoignage est de la fin du XIe siècle, et il a été utilisé, en évoluant

diversement suivant les temps et les lieux, également jusqu'au XVI'

siècle.

Parmi les grands chantres qui se sont succédés à

Notre-Dame de Paris au XIIe siècle, Léonin et Pérotin sont les plus

célèbres. Le premier aurait exercé vers le milieu du siècle, le second

vers la fin du XIIe siècle — début du XIIIe. Léonin était illustre pour

ses compositions polyphoniques à deux voix destinées à enrichir les

chants de la messe et de l'office pour les grands monuments de l'année

liturgique. Ces pièces étaient consignées dans un livre appelé Magnus Liber Organi.

Une génération plus tard arriva Pérotin le Grand

qui modifia certains organums et en composa d'autres trois et quatre

voix.

Léonin

est-il le compositeur de tous les organums à deux voix ? Nous ne le

savons pas. Il est plus prudent de considérer Léonin comme l'élément

catalyseur d'un style qui existait avant lui, mais qu'il a

magistralement illustré. Autour de lui se serait constituée une École de

chantres se situant à l'intérieur de la tradition qu'il avait

magnifiée.

Le Magnus Liber Organi a disparu. Les trois

principaux manuscrits de l'École Notre-Dame qui nous sont disponibles

représentent des compilations plus ou moins fidèles du Magnus Liber Organi. Ils sont postérieurs de plus d'un siècle à la composition de la musique qu'ils renferment.

Les

notations du XIIIe siècle employées pour les pièces du milieu du XIIe

siècle semblent être assimilables aux notations rythmiques mesurées du

XIIIe siècle. Le principe est celui de l'ornementation des intervalles

consonants, les dissonances étant interprétées avec légèreté et

vivacité. Ce sont les chanteurs qui se mettent d'accord sur les notes

qu'ils feront longues et sur celles qu'ils feront brèves. La notation

par elle-même n'indique pas systématiquement le rythme. C'est pourquoi

le traité du Vatican ne parle absolument pas de rythme, tant il est

clair pour l'auteur que c'est le jeu entre les dissonances et les

consonances qui le crée.

Messe du Jour de Noël

Les

concerts de l'Ensemble Organum sont toujours, lorsqu'il s'agit de

musique sacrée, des reconstitutions de liturgies médiévales. Les

différentes pièces qui constituent une liturgie sont pensées pour

s'enchaîner dans un ordre déterminé. Ne pas respecter cet enchaînement

est aussi absurde que d'intervertir les actes d'un opéra. La liturgie

médiévale est un véritable acte dramatique qui s'exprime dans un espace

et un temps rigoureusement déterminés par la tradition rituelle. Les

textes et les musiques qui les portent n'ont une réelle portée que s'ils

interviennent dans la majesté d'un déroulement. Une liturgie est un

tout, ne pas la respecter dans son intégrité non seulement altère la

forme, mais encore trahit l'esprit.

Les limites imposées par la

durée d'un disque nous ont obligés à choisir dans l'unité liturgique les

principaux temps forts qui nous permettent toutefois, en respectant

l'ordre, de suivre le fil conducteur. Les polyphonies enregistrées

peuvent être datées du milieu du XIIe siècle. Elles appartiennent donc à

la période romane de l'École Notre-Dame de Paris.

L'Introït qui

inaugure la Messe est tropé, comme c'était toujours le cas au Moyen-Age

pour les grandes fêtes. Les tropes étaient des commentaires poétiques et

musicaux des chants liturgiques fixés par la tradition. Encore une

fois, nous observons ce sens intarissable qu'avait le Moyen-Age pour

l'ornement et l'enluminure. Chaque commentaire est chanté par un soliste

tandis que le chœur chante l'Introït proprement dit. Le Kyrie est

chanté d'abord par un soliste, puis par le chœur et enfin en quintes et

quartes parallèles.

C'est entre l'Épitre et l'Évangile que

prenaient place les «morceaux de bravoure» des chantres : le Graduel et

l'Alleluia, tous deux chantés en organum. Les organums intervenaient à

des moments précis de l'action liturgique, ici entre les deux lectures.

Ils étaient là pour mettre en relief le sommet de la première partie de

la messe : le chant de l'Évangile. Tout les organums de l'École

Notre-Dame pour le Graduel et l'Alleluia sont bâtis suivant le même plan

:

– Répons : les premiers mots sont chantés en organum, les autres en monodie.

– Verset : tout est chanté en organum sauf les derniers mots.

Après

le chant de l'Évangile la liturgie prend une toute autre couleur. Tout

s'intériorise; maintenant va commencer l'acte mystérieux où le pain et

le vin vont devenir véritablement corps et sang du Christ. La première

partie de la liturgie correspondait, aux premiers siècles du

christianisme, à la messe des catéchumènes. Ceux qui n'avaient pas

encore reçu le baptême étaient renvoyés après la lecture de l'Évangile,

tandis que les initiés restaient pour prendre part aux mystères.

Naturellement, les chants vont avoir un tout autre caractère.

Les

chants d'offertoire, très mélismatiques, étaient les plus longs du

répertoire. L'offertoire du jour de Noël, dont le texte est tiré du

Psaume 88, prend la forme d'une grande méditation cosmique. Il rappelle

l'un des grands thèmes de la spiritualité médiévale : «par le visible,

vers l'invisible».

La Préface s'enchaîne au Sanctus dont les tropes sont chantés en organum par deux solistes.

L'Agnus Dei monodique est ici chanté en mode de sol, alors que

la version adoptée par l'édition vaticane est en mode de

fa.

L'Antienne

de communion reprend la forme, déjà observée dans l'Introït, de la

psalmodie responsoriale (alternance d'un refrain chanté par le chœur et

d'un verset de psaume confié à un soliste).

Une dernière fois, la

méditation se porte sur la dimension universelle et cosmique du mystère

de Noël (viderunt omnes fines terrae...)

L'Ite missa est et le

Deo gratias concluent la liturgie. La mélodie du ténor rappelle le

symbole de la racine de Jessé dont le Christ est la fleur. Les notes du

ténor sont étirées à l'extrême et atteignent presque l'immobilité,

tandis que son enluminure au discantus évolue en ornant continuellement

les intervalles de quinte et d'octave. Pouvait-on trouver un symbole

plus explicite de l'éternité fécondant le temps ?

MARCEL PÉRÉS

From

the mid-twelfth century the Parisian school of singing shone with a

brilliant light throughout Western Christianity by virtue of the quality

of its singers and especially through the art with which they

improvised organums. Polyphonic singing was essentially an art of

improvisation, but in the sense the word “improvise” has in all

societies with an oral tradition. It was, in fact, an art of

centonisation. A certain formula, bound to a particular movement, was

linked to another, and so on, until the mosaic which was thus put

together formed a whole that was harmonious in its proportions.

In their mania for classification, certain music historians have divided the history of Western polyphony into three periods:

— The period of parallel counterpoint, 9th-10th centuries (some writers speak of heterophony).

— The period of counterpoint in contrary motion, 11th century.

— The period of florid counterpoint, 12th century.

The

reality is much more complex. Although the first example of parallel

motion does come from the end of the 9th century, this practice was

still flourishing in the 16th century, and even today certain folk

polyphonies bear traces of it. Contrary motion was known at the end of

the 10th century, but Johannes Scotus Erigena seems to have mentioned

it in the middle of the 9th century. It, too, would be practised in

certain places until the 16th century.

Of the great precentors

who succeeded one another at Notre-Dame in Paris during the 12th

century, Leonin and Perotin are the most famous. The former was in

office around the middle of the century and the latter towards the end

of the 12th and beginning of the 13th centuries. Leonin was celebrated

for his polyphonic compositions for two voices destined for the

enrichment of the chants of the Masses and Offices of the great

liturgical festivals. These pieces were collected together in a book

called the Magnus Liber Organi. A generation later Perotin the

Great modified certain organums and composed others for three and four

voices. Was Leonin the composer of all the two-voice organums? We do

not

know. It is more prudent to consider him as the catalysing element of a

style which had existed before him and which he illustrated in a

masterly manner. A school of precentors grew up around him within the

tradition which he enlarged.

The Magnus Liber Organi has

disappeared. The three principal manuscripts from the Notre-Dame School

which are available to us represent more or less faithful compilations

from the Magnus Liber Organi. They are all over a century later than the music they contain.

The

13th century systems of notation used for these mid-twelfth century

compositions appear to be similar to 13th century measured rhythmic

notations. The principle is that of the ornamentation of the consonant

intervals, while the dissonances are lightly and vivaciously sung. It

was the precentors who agreed on the notes they would make long and

those they would make short. The notation in itself does not

systematically indicate the rhythm. That is why the Vatican Treatise

does not say anything about rhythm: it was perfectly clear to its author

that it was the play between the dissonances and the consonances that

created it.

The Mass For Christmas Day

When

dealing with religious music, the performances of the Organum Ensemble

are always reconstitutions of medieval liturgies. The different pieces

constituting a Liturgy are intended to follow each other in a

determinate order. Not to respect this sequence is as absurd as to

invert the acts of an opera. The medieval liturgy is a veritable

dramatic action which takes place in a space and a time strictly

determined by ritual tradition. The texts and the music that carries

them only have any real significance in so far as they occur in the

majestic context of the unfolding of an event. A liturgy is an entity

and not to respect its integrity not only alters its form, but also

betrays its spirit.

The limits imposed by the length of a single

record obliged us to choose the principle highlights from within the

liturgical unity, but it has nevertheless been possible for us to follow

a continuous line while respecting the order of the pieces. The

polyphonic compositions on the record can be dated around the middle of

the 12th century. They therefore belong to the Romanesque period of the

Notre-Dame School.

The Introit that begins the mass is troped as

was always the case in the Middle Ages on the occasion of a great

festival. The tropes were poetic and musical commentaries on the

liturgical chants fixed by tradition. Once again we may observe the

unfailing sense the Middle Ages had for ornament and illumination. Each

commentary is sung by a soloist while the choir sings the Introit

properly speaking.

The Kyrie is first sung by a soloist then by the choir and finally in parallel fifths and fourths.

It was between the Epistle and the Gospel that the precentors' “bravura pieces” were performed: the Gradual and the Alleluia,

both sung in organum. The organums were sung at precise moments in the

liturgical action, here between two lessons. They were there in order to

set off in relief the climax of the first part of the Mass, the singing

of the Gospel. All the organums for the Gradual and the Alleluia of the

Notre-Dame School are constructed according to the same plan:

– Responsory: the first words are sung in organum, the others in monody.

– Verse: all of it is sung in organum except the last words.

After

the singing of the Gospel the liturgy takes on a completely different

colour. Everything becomes interiorized; now begins the mysterious act

in which bread and wine will become the veritable body and blood of

Christ. Those who had not yet been baptized were sent away after the

reading of the Gospel while the initiated remained behind to take part

in the mysteries. Naturally the chants will take on an entirely

different character.

The highly melismatic chants of the

Offertory were the longest in the repertory. Unfortunately their verses

began disappearing from certain churches during the 12th century,

so that by the end of the Middle Ages the Offertory chants were

reduced to their responsories.

The Christmas Day Offertory, the

words of which come from Psalm 89 (88), takes the form of a great cosmic

meditation. It recalls one of the great themes of medieval

spirituality: “through the visible towards the invisible”.

The Preface is followed by the Sanctus, the tropes of which are sung in organum by two soloists.

The monodic Agnus Dei is here sung in the mode of G, while the version adopted by the Vatican edition is in the mode of F.

The communion antiphon

takes up the form, already seen in the Introit, of responsorial

psalmody (the alternation of a refrain sung by the choir with a psalm

verse sung by a soloist).

The meditation dwells one final moment on the universal and cosmic dimension of the Christmas mystery (Viderunt omnes fines terrae...).

The Ite missa est and the Deo gratias

conclude the liturgy. The melody of the tenor recalls the symbol of the

root of Jesse of which Christ is the flower. The notes of the tenor are

drawn out to the extreme and almost become immobile while the

illumination in the discantus develops in a continuous ornamentation of

the intervals of the fifth and the octave. Could one find a more

explicit symbol of eternity fecundating time?

M.P.