cappellapratensis.nl

challengerecords.com

medieval.org

Challenge Classics 72541

2011

Johannes OCKEGHEM

01 - Introitus. Requiem aeternam [4:25]

02 - Kyrie [4:19]

03 - Graduale. Si ambulem [4:28]

04 - Tractus. Sicut cervus [7:25]

05 - Offertorium. Domine Jesu Christe [8:10]

Piere de la RUE

06 - Introitus. Requiem aeternam [4:18]

07 - Kyrie [2:47]

08 - Tractus. Sicut cervus [3:26]

09 - Offertorium. Domine Jesu Christe [6:45]

10 - Sanctus [5:04]

11 - Agnus Dei [3:24]

12 - Communio. Lux aeterna [2:42]

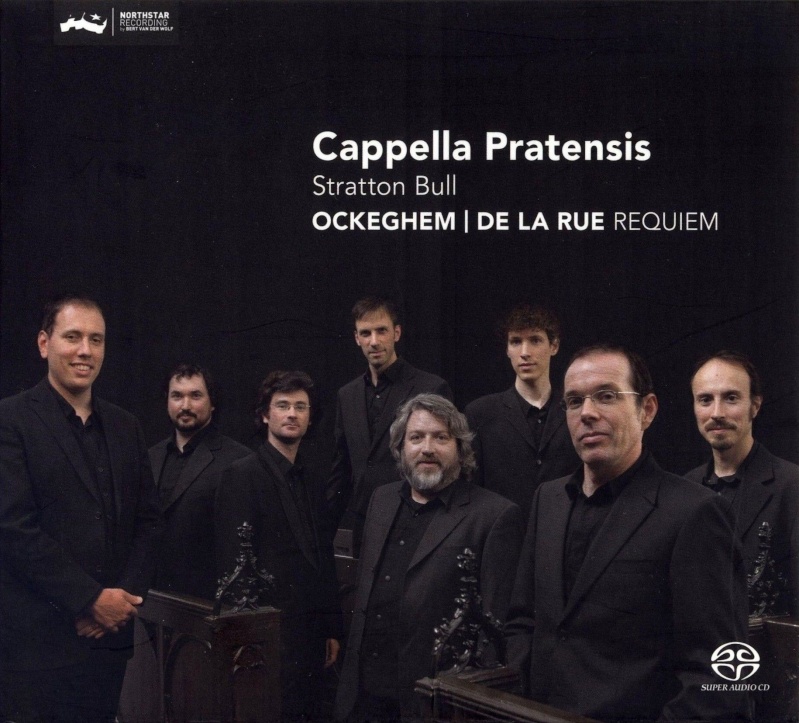

Cappella Pratensis

Stratton Bull

Stratton Bull, superius

Andrew Hallock, superius

Christopher Kale, altus

Lior Leibovici, altus

Olivier Berten, tenor

Peter de Laurentiis, tenor

Lionel Meunier, bassus

Pieter Stas, bassus

Executive producer: Anne de Jong

Recording location: Church of Vieusart (Belgium)

Recording dates: 9-12 June, 2011

Recording producer: Bert van der Wolf

Recorded by: NorthStar Recording Services

Photography: Vincent Nabbe

The Requiems by Ockeghem and La Rue

This recording presents the two earliest surviving polyphonic Requiems,

by Johannes (Jean de) Ockeghem and Pierre de La Rue, both among the few

major Netherlandish composers of the time not to have spent significant

portions of their careers in Italy. Little is known of the early career

of La Rue (c. 1452-1518), but from 1492 he served successive rulers in

the Habsburg-Burgundian chapel alongside equally distinguished

musicians, first under Maximilian, then Philip the Fair (with whom he

travelled twice to Spain), and finally, the cultivated and tragic

figure of Marguerite of Austria, regent of the Netherlands, for whom

many of his most beautiful sad songs were written.

Ockeghem died in 1497; his birth date has been estimated at several

years on either side of 1420. He is first documented as an adult singer

in Antwerp in 1443, then in the service of Charles, Duke of Bourbon,

before entering the French royal chapel in the 1450s. He enjoyed the

patronage of Charles VII who nominated his first chaplain to the

lucrative position of treasurer of St Martin in Tours, a favour

continued under Louis XI. He was held in the highest repute in his

lifetime, alongside Du Fay and Busnoys (with both of whom he had direct

contacts), Binchois (on whose death in 1460 he wrote a

Déploration), Josquin, and other composers less well known to

us. Johannes Tinctoris honoured him in two treatises of the mid 1470s;

he was much cited by contemporaries and throughout the next century,

even after direct knowledge of his music was no longer current. Kindly,

benign, pious, and of irreproachable virtue — this is the image

that has come down to us. His death was lamented in at least two

musical works: Busnoys's In hydraulis and Josquin's Nymphes

des bois, adapted from a poem by Jean Molinet enjoining major

contemporary composers to lament their 'good father', and in a long

poetic Déploration by Guillaume Crétin.

The earliest liturgical chants to receive polyphonic elaboration, in

the twelfth century, had been for joyful occasions of the church year;

the latest, in the fifteenth, were for seasons of mourning, both the

Passion and death of Christ, and human commemoration, for which the

Church has abidingly discouraged musical adornment. The earliest

polyphonic Requiems are, accordingly, restrained and austere,

understated in comparison with the normal musical styles of their

composers, in fewer parts, and relatively homophonic. Whereas most Mass

Ordinaries composed around 1500 set all five movements on a unifying

musical theme or model, early Requiems base each movement on its

corresponding chant; while there may be an overall sombre mood, the

sections are not thematically unified. In Ockeghem's case, the chants

are usually in the superius and only lightly embellished, which already

makes for a more archaic effect; in La Rue's Requiem the chant is often

in the tenor but permeates the other parts imitatively. Other early

settings were composed by Févin (or Divitis), Brumel, Richafort,

Prioris, and anonymous composers including some Spaniards. There is no

standard practice as to which movements are set. Ockeghem sets the

Introit, Kyrie, Gradual, Tract and Offertory but not the Sanctus, Agnus

and Communion; La Rue sets the Introit, Kyrie, Tract, Offertory,

Sanctus, Agnus and Communion but not the Gradual. The Dies irae,

which dominates most later Requiems, was one of the few Sequences to

survive the liturgical reforms of the Council of Trent but, of these

composers, only Brumel sets it. It was usually omitted in early

northern European Requiems, whose texts differ from Roman and southern

European traditions, with some variants in the Offertory, and use of

the Gradual Si ambulem and the Tract Sicut cervus,

instead of Requiem aeternam and Absolve domine.

Each of the present settings is preserved in a manuscript from the

famous Alamire workshop (respectively Vatican Library, MS Chigi C VIII

234, and Jena, Universitätsbibliothek, Chorbuch 12). The primacy

of Ockeghem's gives it special significance for us, but it did not have

a circulation commensurate with his reputation; its transmission was

extremely fragile, in a single source and with many anomalies. By

contrast, La Rue's Requiem was much more widely copied, in six

manuscripts including some from the Bavarian court.

But there was one earlier Requiem which has not survived, by Guillaume

Du Fay (d. 1474), whose will prescribed in detail the arrangements for

his deathbed and funeral. His polyphonic Requiem was to accompany his

own biannual post mortem commemorations, and was requested by others in

the ensuing decades. Its afterlife was clearly much more vigorous than

Ockeghem's Requiem. In 1501, the Order of the Golden Fleece replaced

its weekly monophonic Requiem with Du Fay's setting, described by an

ear-witness as being for three voices, sad, solemn and very sweet (una

Messa a tre voci, flebile, mesta e suave molto). This implies a texture

much sparser than that of his lush four-part late masses, and indeed

could well apply to portions of Ockeghem's setting, notably the Introit

and Kyrie, to the extent that a few scholars have speculated whether

'Ockeghem's' Requiem could in fact be the 'lost' setting by Du Fay. But

this is belied by the richer four-part sections, especially the

elaborate rhythms of the Offertory, depicting infernal torments.

Indeed, the many stylistic contrasts and anomalies within the Ockeghem

Requiem are puzzling, notwithstanding brave attempts to argue their

coherence. The ninefold Kyrie, in particular, with its alternating

sections in two and three parts, has no precedent in Ockeghem's masses

but, apart from the final four-part section, uses a compositional

technique favoured by Du Fay and other composers of the previous

generation, and shows signs of adaptation from an earlier work. I have

tentatively suggested that Ockeghem may have incorporated some portions

of Du Fay's setting, adding and substituting sections of his own,

including all the four-part sections, and the entire Offertory, which

is strikingly different, and much closer to what we know of Ockeghem's

style elsewhere. His visits to Du Fay in Cambrai in 1462 and 1464

provide opportunities for the mutual influence that has been detected

in their compositions. Ockeghem also visited Cambrai in 1483, just two

weeks before one of the commemorations for which Du Fay had stipulated

his Requiem. He could have been present, at or even sung in it; the

restrained style implied by the description could at the very least

have inspired his own setting.

Although Ockeghem's Requiem uses no more than four notated parts at any

one time, only a tiny percentage, less than a fifth of the music, is

actually in four parts (the final sections of the Kyrie, Gradual and

Tract, and two sections of the Offertory). There are rather few

sections with reduced scoring in his other masses, making the

predominance of two and three-part writing in the Requiem all the more

striking. And yet, at least six voices (here, eight) are needed to cope

with the various combinations. Notated pitch was not tied to a standard

frequency, and low notation may in some cases have been symbolic. Other

masses show discrepancies of register; the movements of La Rue's much

more homogeneous setting are also notated at different levels. In that

case (unlike Ockeghem's) they can be brought closer together by

transpositions, the approach that has been taken for this recording.

The Chigi manuscript is the unique source for most of Ockeghem's

thirteen mass groupings; it may have been intended as a memorial

volume, an only partially successful attempt to assemble his complete

works. Some of those masses are patently incomplete, and we know he

wrote others that have not survived. The Requiem is an extreme case of

problematic transmission. If, like Mozart, Ockeghem had died in the

middle of composing his Requiem, Crétin (in the

Déploration referred to above) might not have described it as

'exquise et très-parfaicte'; even allowing for funerary

hyperbole, this is hardly an apt description of the incomplete and

inconsistent work that has come down to us, however beautiful we may

find it. But Crétin's testimony cannot be dismissed; he was a

musically knowledgeable professional, a cantor at the Sainte Chapelle,

a chaplain to François I, and held the position of treasurer at

Vincennes, parallel to that of Ockeghem at Tours. (Another reference

much later in the poem enjoins choirboys not to improvise florid but

only simple counterpoint on the Requiem chant; this probably does not

refer to Ockeghem's composition.) The Chigi scribe may have compiled

the work to the best of his ability from a miscellaneous assembly of

working drafts bearing Ockeghem's name, perhaps even including copies

of some sections of Du Fay's Requiem which Ockeghem was in process of

amplifying, more in the spirit of homage than of plagiarism. The result

shows some signs of being a work in progress. Was his Requiem

incompletely composed or incompletely transmitted? It is very uncertain

whether Crétin was describing it in the form in which we know it.

La Rue was a generation younger, but his Requiem is probably not much

later in date. (His motet-chanson Plorer, gemir, crier/Requiem,

based on the Introit for the Requiem Mass, may be a lament on the death

of the older composer.) Although all movements are likewise built on

their corresponding chants, they make a much more unified stylistic

impression than Ockeghem's. There is more imitation and chordal

declamation, and some near-canonic duet writing. La Rue's masterly

setting is mostly in four parts, but the Tract Sicut cervus is

set as two long duets, and some sections of the Kyrie, Offertory,

Sanctus and Agnus expand to five.

Given the Church's strictures against musical embellishment for rites

of mourning, it is a wonder that they ever received polyphonic

settings. This is where it started: these first settings prepared the

way for later great cornerstones of the western musical tradition such

as the Requiems of Mozart and Verdi.

Margaret Bent