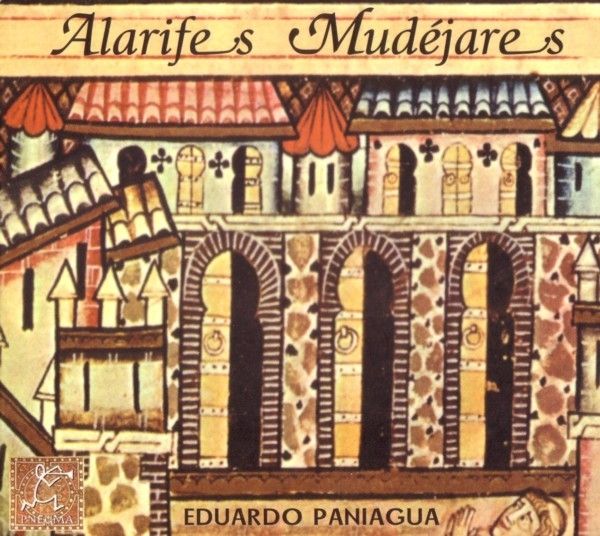

Alarifes Mudéjares / Eduardo Paniagua

Música para la iglesia mudéjar de San Martín de

Cuéllar

medieval.org

Pneuma «Colección Al-Andalus» PN-170

1999

1. Secuencia constructiva. Pilares, arcos, bóvedas [7:34]

Melodía sobre

original andalusí

modo Hiyáz oriental · ritmo: Qáim wa nisf

psalterio, flautas tenor y alto y cántara

teclado: arpa, santur, qanún, efecto base (emoción)

efectos: cantero, yesero, sierra de madera, yunque, grillos, ranas y

sapos

2. La barca. Tierra de nadie [2:50]

Melodía sobre

canto mozárabe ‘Surgam’

Antifonario de Silos

flauta tenor

teclado: efecto base, campanillas

efectos: barcos en el puerto

3. La fuente. Arte efímero-arte eterno [2:08]

Melodía sobre

original andalusí

modo Hiyáz oriental · ritmo: Qáim wa nisf

laúd, salamilla (flauta de caña), fahl (flauta

árabe metálica), darbuga y tar

teclado: dulcimer y pedal de efecto base

efectos: fuente de agua de jardín hispano-musulmán.

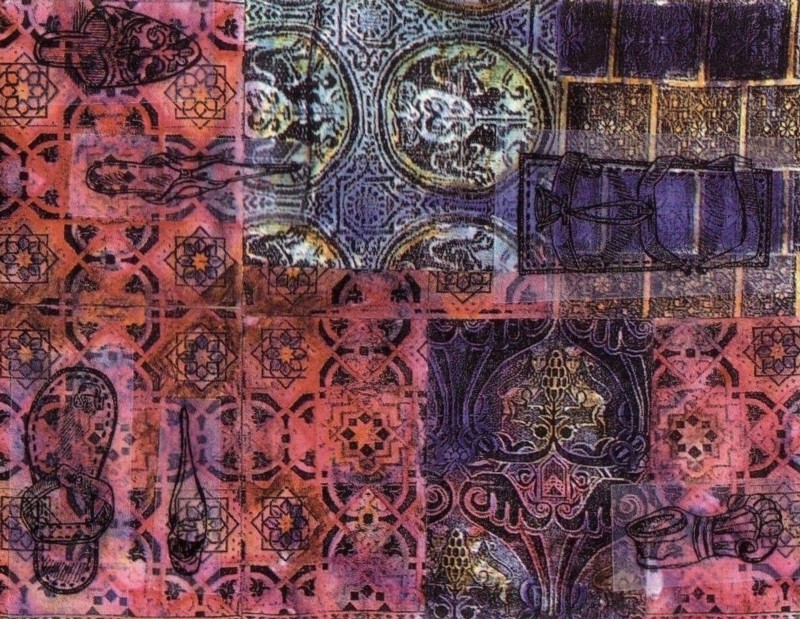

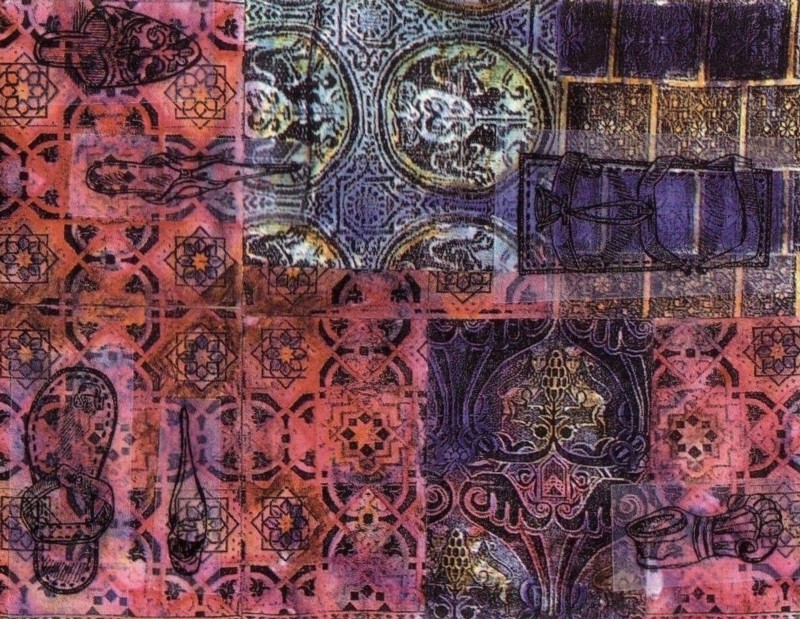

4. La alfombra. Arte colectivo y espacio colectivo [2:26]

Llamada a la

oración desde el alminar

cantor: Hasan Ajyar.

cantos de ceremonia judía, canto gregoriano: "Veni Creator

Spiritus"

campanas de iglesias: cercana y lejana

teclado: efecto base

5. Las velas. De pronto se llenó [6:56]

CSM 180

Melodía sobre

la cantiga 180

Cantigas de Santa María de Alfonso X el Sabio, siglo XIII

flauta travesera de catia, flauta tenor, santúr, viola,

campanillas y cántara

teclado: efecto base

6. Almuédano [3:19]

Llamada a la

oración andalusí

cantor: Said Belcadi

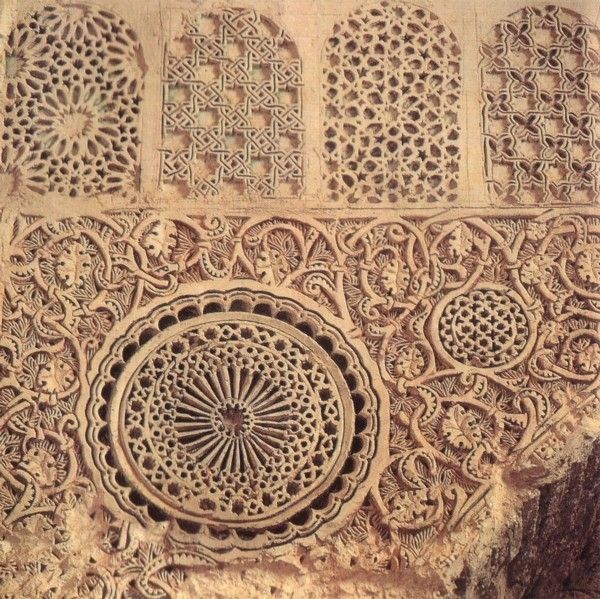

7. Yeserías [2:19]

Solo nay de sobre

modo andalusí

nay (flauta oblicua de caña)

8. Baños y aljibes [:39]

Canto libre

andalusí en los modos Rasd y Nahawand

cantor: Said Belcadi.

efectos: chorros de agua, bañera llenándose, gotas y

teclado base

9. Fiesta de Santa María [6:32]

CSM 411

Melodía sobre

la cantiga 411

Cantigas de Santa María de Alfonso X el Sabio, siglo XIII

viola, laúd, axabeba, fahl, cántara, darbuga y tar

teclado: efecto base

10. En el atrio [5:59]

Melodía de

nay sobre modo andalusí

nay, bendir y tambores

11. Albañil mudéjar [3:46]

Canto libre sobre

modo andalusí

cantor: Abedelhamid Al-Haddad

cántara, percusiones metálicas de darbuga

efectos: tallado sobre piedra, martillo sobre metal, martillo de forja

12. Capilla de azulejos [7:19]

CSM 418

Melodía sobre

la cantiga 418

Cantigas de Santa María de Alfonso X el Sabio, siglo XIII

viola, laúd, citolón, cistro, kaval, gaita charra, tar

y címbalos

teclado: efecto base

13. Oración de mediodía [2:30]

Canto de

almuédano andalusí

Abderrahim Abdelmoumen

efectos: niños en la plaza, pájaros, campanas de "angelus"

Canto andalusí:

Said Belcadi · Abedelhamid Al-Haddad · Hasan Ajiyar

· Abderrahim Abdelmoumen

Abdelouahíd Acha, nay

Jaime Muñoz, flauta travesera de caña

Wafir Sheik, laúd

Cesar Carazo, viola

Luis Vincent, cistro

Luis Paniagua, cántara

Luis Delgado, santur, citolón, laúd, bendir,

cántara

Enrique Almendros, gaita charra, campanillas y címbalos

Eduardo Paniagua

psalterio, flauta tenor y alto, salamilla (flauta de caña),

fahl (flauta árabe metálica),

darbuga, tar, címbalos, teclados/efectos/ambientes

Grabaciones realizadas en los años 1995, 1997 y 1999

Toma de sonido natural de los cantos: Eduardo Paniagua

Masterizado: Hugo Westerdahl - Axis, Madrid 1999

Agradecimiento a Luis Delgado por su apoyo en esta grabación

DDD ·

59:16

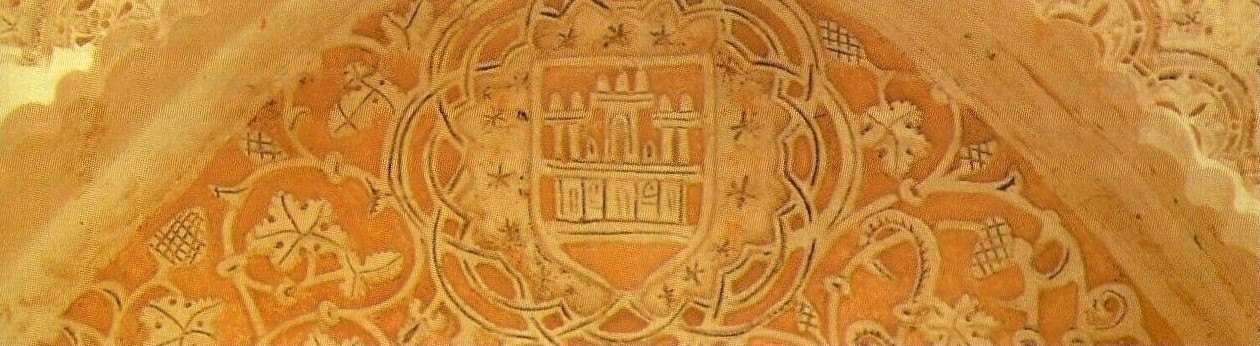

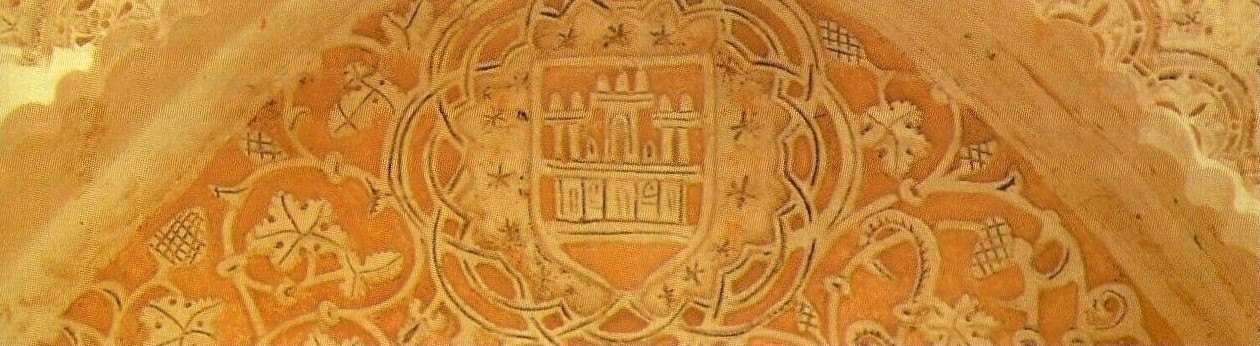

Portada: Cantigas de Santa María de Alfonso X el Sabio, s. XIII.

Detalle de construcción mudéjar de la miniatura 111

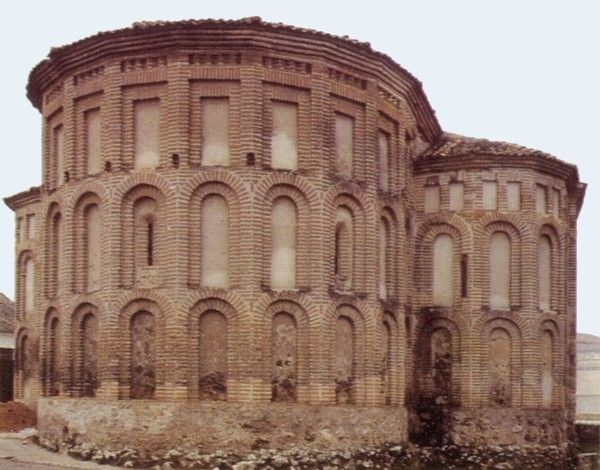

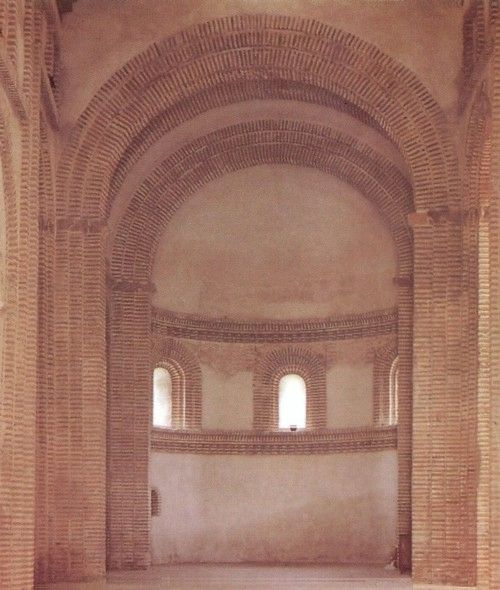

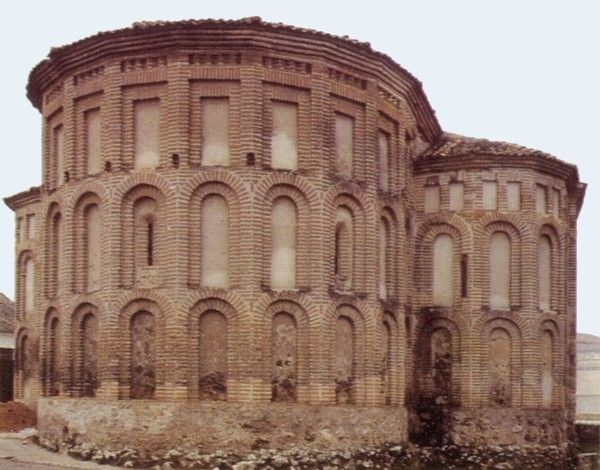

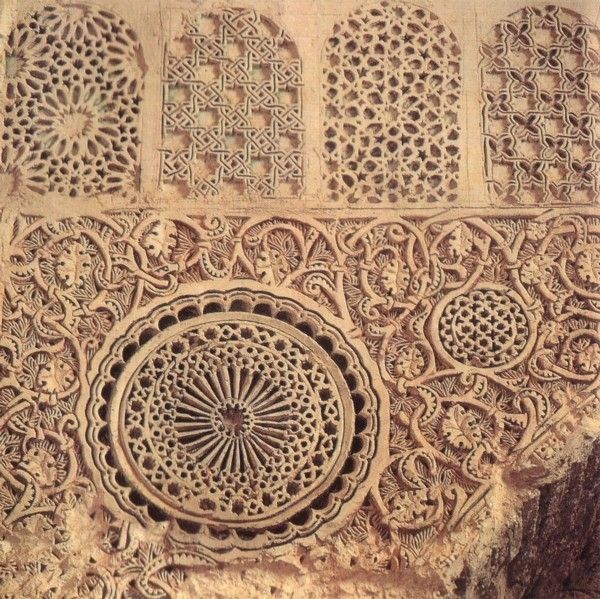

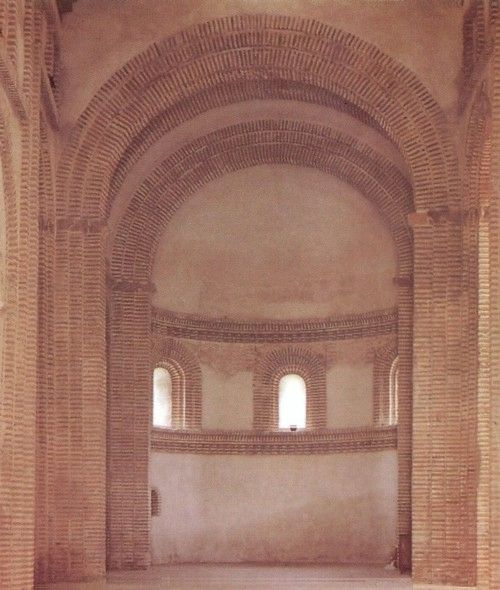

Contraportada e interior: Detalles de la iglesia de S. Martín de Cuéllar.

Diseño gráfico: Luis Vincent

Translation: Lesley Ann Shockhurgh

Depósito Legal: M-25643-1999

Distribución: Karonte, Madrid.

Producción: EDUARDO PANIAGUA • 1999 PNEUMA

PLAN DE DINAMIZACION TURÍSTICA •

CUÉLLAR

ISLA MUDÉJAR EN UN MAR DE PINARES

English liner notes

Alarifes Mudéjares

EDUARDO PANIAGUA

Música para la iglesia mudéjar de San Martín de

Cuéllar

La realidad histórica de la España medieval está

configurada por la convivencia de las tres castas: cristianos,

judíos y musulmanes.

Uno de los aspectos más sugerentes de esta integración se

manifiesta en el mudejarismo, entendido como proceso de

islamización de la sociedad hispánica desde la Edad Media

hasta siglos después, en la pervivencia de costumbres, oficios,

técnicas artesanales y manifestaciones artísticas.

Otro aspecto del mudejarismo es la influencia cristiana en los

musulmanes, criticada por los autores árabes de la época.

Imágenes emblemáticas de estas dos caras de la moneda son

las miniaturas de las Cantigas de Santa Maríia y del Libro de

Ajedrez, Dados y Tablas de Alfonso X el Sabio, con escenas de

musulmanes jugando con caballeros y damas cristianos y judíos.

Comúnmente se entiende como mudéjares, del árabe

"mudayyan", sometido o tributario, a los musulmanes que no emigraron y

permanecieron bajo el poder político de los reinos cristianos.

Como categoría artística el mudéjar se asimila al

arte románico y al gótico cristiano islamizado

profundamente, y no solo a la simple yuxtaposición de formas

decorativas islámicas sobre estructuras arquitectónicas

occidentales.

La selección, instrumentación y ambientación de la

música de este disco está inspirada en la iglesia

mudéjar San Martín de la ciudad de Cuéllar, en la

provincia de Segovia de la región de Castilla y Leon.

EDUARDO PANIAGUA

Cultura de Frontera

Tras la conquista de Toledo en 1085, Alfonso VI comenzó la

repoblación y la fundación de ciudades. "La tierra de

nadie se convirtió en tierra de todos." Y llegaron del norte:

Galicia, Tierra de Burgos, La Rioja, Navarra y Vasconia. Del sur: moros

de Toledo. De todas partes o de ninguna: los judíos.

Y se encontraron con algunos -pocos- que estaban desde hace tiempo:

descendientes de antiguas poblaciones árabes visigodas,

hispano-romanas e incluso con reminiscencias celtíberas.

Unos trajeron su saber trabajar la tierra, las técnicas de riego

o la albañilería, otros esperanzas y futuro y todos

dejaron casas, amigos, familias, hambre y paisajes. Entre todos

construyeron una cultura de frontera y una comunidad de hombres libres

"la comunidad de villa y tierra".

Tierra de Nadie

"Lo que dejaron y lo que trajeron..." Qué dejaron: barcas,

nieblas, hayedos, llaves de las casas, familias, amigos, ajuar, puertas

de las casas, redes. Qué trajeron: olores, colores, manos,

tecnologías, herramientas, religiones, canciones, niños,

semillas, amantes de la libertad y la fortuna, etc...

La Extremadura castellana, las tierras del río Duero, se

hicieron un espacio de convivencia. "Los hombres abandonaron sus

antiguos solares en busca de libertad y de fortuna, pero

jugándose la vida en el envite". "Un islote de gentes libres en

Castilla", pero los árabes que trajo Alfonso VI desde Toledo

eran "sometidos" mudéjares.

El Mudéjar, el arte más genuinamente español

Un arte hecho de ventanas y puertas, de líneas

geométricas, de elementos decorativos -vegetales y

epigráficos- de repetición y ritmos, de oración

colectiva y espacio individual.

Un arte hecho de ventanas y puertas, de líneas

geométricas, de elementos decorativos -vegetales y

epigráficos- de repetición y ritmos, de oración

colectiva y espacio individual.

Lo decorativo no es superficial, tiene un profundo sentido. La ausencia

de iconografía, aunque el mudéjar la tiene

después, también tiene un sentido.

La albañilería mudéjar es la manifestación

artística genuina de un momento histórico en Castilla y

León que se concreta singularmente en Cuéllar.

La iglesia de San Martín refleja la belleza y el misterio de lo

vivido, de lo que se llenó, contempló, vibró y

tembló y ahora está vacío, callado.

Entrar en esta iglesia es comenzar un viaje. Un pequeño viaje

iniciático del que nunca se regresa impune, del que retornaremos

distintos, más viejos pero algo más sabios. Un viaje

hacia un universo, hacia un mundo singular, el de la frontera, el de la

mixtura y convivencia de culturas. En este recorrido nos adentramos en

la tierra de nadie, participamos en la emigración, compartimos

el abandono y la añoranza y el futuro y la esperanza -lo que

dejaron y lo que trajeron-, el descubrimiento del otro y el nacimiento

de la identidad, una cultura de "hombres libres" y "sometidos". Todas

esa memoria, esa cultura no está perdida sino atesorada en un

espacio vacío, en un ciudad, en unos rostros, en el fondo de

arena de unas miradas, de unos gestos, esperando ser redescubiertos.

Entrar en una iglesia mudéjar es penetrar en un universo donde

cada pieza tiene su sentido, es recuperar aromas, es abrir ventanas y

puertas, zaguanes que esconden olores y sabores, signos y

símbolos de tierra, marcas en la piel, canciones, juegos de

niños, memoria y recuerdo, sonidos de oraciones y gritos,

barrios, calles y espacios que habitaron sinagogas, que escucharon los

cantos de los muecines, de los soldados, de los clérigos, es

acercarse al punto donde la ciudad aunque parece dormida, palpita.

Arte efímero / arte eterno

"Los repobladores hubieron de improvisarlo todo..." y de esa vida de

frontera, de peligro, inseguridad y esperanza, fusión de

culturas y saberes surge este arte efímero, circunstancial,

humilde pero casi eterno. Las grandes piedras del páramo

están lejos, en tierra de peligro, de razias, y es mejor

utilizar materiales cercanos, básicos y humildes: arcilla,

barro, pequeñas piedras, agua, cal y madera.

La lana de las ovejas permitió la financiación y

así, unos pagaban -el concejo y el cabildo-, los alarifes

-albañiles árabes- dirigían y la comunidad -todos-

trabajaban.

Arte colectivo y espacio colectivo

La iglesia de San Martín de Cuéllar es una

creación colectiva, anterior a cualquier autor. Reflejo de una

sociedad comunitaria, de un tiempo y una cultura de

colaboración. Una sociedad de tres culturas.

Tres religiones distintas y un solo Dios verdadero. Aquí y con

diferentes rituales se celebraban los ciclos de la vida: la llegada al

mundo, los pasos del crecimiento, los compromisos, o la muerte. La

campana convivía con el muecín, la Biblia y el Talmud con

el Corán. La Navidad, la Cuaresma y el Ramadán,

Aid-elkebir o Bar-Mitzvah. La iglesia era Casa del Pueblo, espacio de

reunión y representación. Allí se conjuraban

pestes y se pregonaban rogativas. Se realizaban promesas y llegaban las

noticias. Era almacén (diezmos y primicias) y atrio para la

venta e intercambio. Lugar de exvotos y reliquias. Espacio de

reunión, hospitalidad y refugio. La escuela donde se

enseñaba a leer y a escribir.

Y además estaban las campanas y su lenguaje: toques de

oración (amanecer, angelus, atardecer, vísperas),

difuntos (diferentes para niños, hombres o mujeres), para

ahuyentar las nubes, reuniones colectivas y del concejo, toques de

rebato (peligros y socorros colectivos), las campanas del reloj y el

tiempo.

"Y de pronto se llenó..." Las iglesias que estuvieron desnudas

se llenaron de sonidos y objetos, los elementos decorativos se

combinaron con las imágenes.

Eusebio Leránoz

ICN-ARTEA

1. Constructive Sequence. Pillars, arches, vaults —

Melody based on an andalusi original. Mode: Oriental Hidyaz. Rhythm: Qaim wa nisf.

2. The Boat. No man's land —

Melody based on a Mozarabic song "Surgam" from the Antiphonary at Silos.

3. The Fountain. Ephemeral art-Eternal art —

Melody based on an andalusi original. Mode: Oriental Hidyaz. Rhythm: Qaim wa nisf.

4. The Carpet. Collective art and collective space —

Call to prayer from the minaret, voice: Hasan Ajyar.

Songs from the Jewish ceremony. Gregorian chant. "Veni Creator Spiritus" and bells.

5. The Candles. Suddenly it filled up —

Melody based on Cantiga 180 from Alfonso X's "Cantigas of Holy Mary".

6. Muezzin —

Andalusi call to prayer, voice: Said Belcadi.

7. Plasterwork —

Nay solo (an end-blown reed flute) in an andalusi mode.

8. Baths and cisterns —

Free andalusi song in the Rasd and Nahawand modes, voice: Said Belcadi.

9. Feast of Holy Mary —

Melody based on Cantiga 411, "Cantigas of Holy Mary", Alfonso X the Wise. XIII century.

10. In the Atrium —

Nay melody in an andalusi mode.

11. Mudéjar Bricklayer —

Free song in an andalusi mode, voice: Abedelhamid Al-Haddad.

12. Chapel of Tiles —

Melody based on Cantiga 415, "Cantigas of Holy Mary", Alfonso X the Wise. XIII century.

13. Midday Prayer —

Andalusi muezzin chant: Abderrahim Abdelmoumen.

Music for the Mudéjar church of St. Martin at Cuéllar

Spain's medieval history is marked by the coexistence of three civilizations - Christians, Jews and Muslims. Mudéjarism

represents one of the most relevant aspects of this integration,

surviving in customs, trades, arts and crafts, and defined as a process

of Islamization of Hispanic society through the Middle Ages and the

following centuries.

Another aspect of Mudéjarism is the Christian influence on the Muslims, criticized by Arab creators of the time.

The miniatures in Alfonso X's "Cantigas

of Holy Mary" and the "Book of Chess, Dice and Astronomical Tables",

with scenes of Muslims playing with Christian and Jewish Knights and

ladies, are emblematic of these two sides of the Mudéjar coin.

Normally the word Mudéjar

is used to describe the Muslims who did not emigrate and remained under

the political power of the Christian kingdoms. The word comes from the

Arabic, "mudayyan", meaning subjected or tributary.

As an artistic category the Mudéjar

resembles Romanesque art and profoundly Islamized Christian Gothic, and

is not simply the juxtaposition of Islamic decoration on western

architectural forms.

Mudéjar is not a style arising from

circumstance, but the artistic option of the expression of a culture,

different from European Christian art, chosen for the architecture of

churches and palaces, not only by the citizens, but also by the ruling

class.

The choice of the music for this recording, the instrumentation and atmosphere are inspired by the Mudéjar church of St. Martin in the town of Cuéllar, province of Segovia in the region of Castile and Leon.

EDUARDO PANIAGUA

Frontier Culture

After

the conquest of Toledo in 1085, Alfonso VI embarked on the repopulation

and founding of cities. "No man's land became everybody's land."

People

came from the north - Galicia, Burgos, La Rioja, Navarre and the Basque

Country. From the south - the Moors from Toledo. And the Jews came from

everywhere, or from nowhere.

These peoples found themselves with

other peoples, the few that had been there for some time, descendants

of ancient Arab, Visigoth, Hispano-Roman and even Celtic, settlements.

Some

brought knowledge of how to work the land, of irrigation techniques or

of bricklaying, others brought hope and future. They all left their

homes, friends, families, hunger and familiar landscapes. Between them

they built a frontier culture and a community of free men "the community

of town and land".

No man's land

"What they

left and what they brought..." What they left - boats, fog, beech

groves, keys to their houses, families, friends, furnishings, doors,

nets. They brought smells, colours, hands, technology, tools, religions,

songs, children, seeds, lovers of freedom and fortune, etc...

The

Extremadura of Castile, the area around the river Duero, became an area

of coexistence. "Men abandoned their old land in search of freedom and

fortune, but they risked their lives in the attempt". "An island of free

peoples in Castile", but the Arabs that Alfonso VI brought from Toledo

were "subdued" Mudéjars.

Mudéjar, Spain's most genuine art form

An

art form comprising windows and doors, geometric lines, decorative

elements -plant motifs and epigraphs- repetition and rhythms, collective

prayer and individual space.

The decorative part is not superficial, it has a profound meaning. The absence of iconography, although found in later Mudéjar style, is also significant.

Mudéjar

brickwork is the genuine artistic manifestation of a historic moment in

Castile and Leon, which is cemented particularly in Cuéllar.

The

church of St Martin reflects the beauty and mystery of the life it has

seen, of what filled it, what it saw, what made it vibrate and tremble.

Now it is empty and quiet.

To go into this church is to start a

journey. A journey of initiation which will never leave you untouched,

from which we will return changed, older but a little wiser. A journey

towards the universe, towards a special world, a frontier world, that

represents the mixture and coexistence of cultures. On this journey we

enter no man's land. We join in the emigration, we share in the

abandonment and the nostalgia and the future and hope - what they left

and what they brought -, the discovery of something new and the birth of

an identity, a culture of "free men' and "subdued men". All these

memories, this culture, are not lost but accumulated in an empty space,

in a town, in faces, in the sandy depths of eyes and gestures, waiting

to be rediscovered. To go into a Mudéjar church is to penetrate a

universe where everything has a meaning. Aromas are rediscovered, doors

and windows are opened, revealing halls that hide smells and flavours,

signs and earth symbols, marks on the skin, songs, children's games,

memory and memories, sounds of prayer and shouts, neighbourhoods,

streets and spaces once occupied by synagogues, spaces that heard the

chants of the muezzins, of the soldiers, of the clerics. We approach the

point where the town, whilst appearing to be asleep, beats.

Ephemeral art/eternal art.

"The

people who repopulated had to improvise everything..." and from this

frontier life, a life of danger, insecurity, and hope, a fusion of

cultures and wisdom, emerges this ephemeral art, circumstantial, humble

but almost eternal.

The great stones of the plain are far away,

in a land of danger, of forays, and it is better to use materials that

are close by, basic and humble - clay, mud, pebbles, water, lime and

wood.

Wool from the sheep provided the money, and thus some paid

the town council - whilst Arab bricklayers gave the orders, and the

community -everybody- worked.

Collective art and collective space

The

church of St Martin at Cuéllar is a collective creation, prior to any

creator. It reflects a community society, at a time and in a culture of

collaboration. A society of three cultures.

Three different

religions and one true God. Here the cycles of life were celebrated with

different rituals - arrival in the world, growing up, maturity, or

death. The bell lived in harmony with the muezzin, the Bible and the

Talmud with the Koran. Christmas, Lent and Ramadan, Aidelkebir or

Bar-Mitzvah. The church was the House of the People, a space to meet and

a place of representation. Curses were pronounced and prayers said.

Promises were made and news arrived. It was a warehouse (tithes and

first-fruits) and the place for selling and exchange. A place for ex votos

and relics. A space for meetings, hospitality and refuge. The school

where reading.and writing was taught. There were the bells and their

language - peals for prayer (at dawn, angelus, evening, vespers), for

the deceased (one for children, another for men or women), peals to

disperse the clouds, to call a meeting and to convene Council, peals of

alarm (collective dangers and distress), to tell the time and give a

weather forecast.

"And suddenly it filled up..." The churches

that were naked were filled with sounds and objects, the decorative

elements combined with the images.

Eusebio Leránoz, ICN-ARTEA

Un arte hecho de ventanas y puertas, de líneas

geométricas, de elementos decorativos -vegetales y

epigráficos- de repetición y ritmos, de oración

colectiva y espacio individual.

Un arte hecho de ventanas y puertas, de líneas

geométricas, de elementos decorativos -vegetales y

epigráficos- de repetición y ritmos, de oración

colectiva y espacio individual.