medieval.org

Turnabout TV 34871

1973

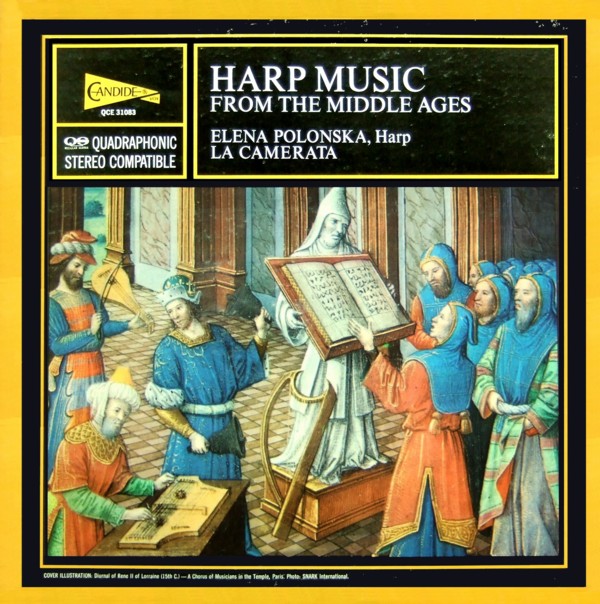

Candide QCE 31083 / Candide (FSM) CE 31083

FSM 53016

1974

medieval.org

Turnabout TV 34871

1973

Candide QCE 31083 / Candide (FSM) CE 31083

FSM 53016

1974

SIDE I [20:31]

Band 1 [6:50]

1. Anon. (13th cent.). Estampie anglaise [1:56]

— vièle, recorder, Irish harp, zarb

2. Blondel de NESLE (12th cent.).

A la entrée de l'esté [1:15]

— Irish harp

3. Notre Dame School (ca. 1250). Motet Pucelete [0:48]

— medieval harp, lute, recorder

4. THIBAUT IV, king of Navarre (ca. 1201-1253).

Pour ce se d'amer me dueil [1:26]

— vièle, percussion

5. Anon. (13th cent.). Elend, du hast umfangen mich [1:26]

— Irish harp

Band 2 [8:01]

6. Anon. (13th cent.). Istampitta Ghaetta [4:02]

— recorder, medieval harp, zarb, tambourine

7. Gautier de COINCY (12th cent.).

Ma vièle [1:43]

— vièle, Irish harp,

8. Alfonso X "The Wise" (1221-1284).

Cántiga [1:10]

CSM 166

— psaltery, percussion

9. Anon. (13th cent.). Danse royale [1:06]

— Irish harp, percussion

Band 3 [5:40]

10. Magister PIERO (14th cent.).

Chavalcando con un giovin accorto [1:32]

— Irish harp, lute

11. Giovanni da FLORENTIA (ca. 1330).

Io son un pellegrino [2:00]

— Irish harp, lute

12. Francesco LANDINI (1325-1397).

Nel mio dolce sospir [2:08]

— Irish harp, lute, recorder

SIDE II [16:46]

Band 1 [6:06]

13. Raimbault de VAQUEIRAS (?-1207?).

Kalenda maya [2:19]

— vièle, recorder, Irish harp, zarb

14. Notre Dame School (13th cent.). Clausolae Haec dies [1:56]

— Irish harp

15. Anon. (13th cent.). Saltarello [1:52]

— rebec, recorder, Irish harp

Band 2 [6:01]

16. Anon. (13th cent.). Chanson de Toile [1:25]

— medieval harp

17. Oswald von WOLKENSTEIN (1377-1445).

Wach auff, myn hort [0:58]

— vièle, lute

18. Anon. (13th cent.). En mai la rousée [1:06]

— medieval harp

19. Notre Dame School (13th cent.). Flos filius eius [1:06]

— medieval harp, psaltery, vièle

20. Anon. (13th cent.). La Rossignol [1:07]

— recorder, rebec, medieval harp

Band 3 [4:39]

21. Bernart de VENTADORN (12th cent.).

"Vers" provençal [2:32]

— Irish harp

22. Anon. (13th cent.). Estampie royale [1:46]

— recorder, vièle, Irish harp, tambourine

23. Anon. (13th cent.). Trop penser me font amours [1:116]

— medieval harp

24. Anon. (13th cent.). Estampie royale [0:36]

— schalmey, vièle, percussion

" I must point out that I have specially chosen the pieces which are here recorded

for their agreeable and entertaining character;

and although this music is from the distant past, I feel that the listeners in listening to it

will derive the same pleasure as the interpreters did in playing it."

(Elena Polonska)

The role of instruments in the music of the Middle Ages is not clearly

defined: bowed instruments, plucked instruments and wind instruments

were numerous; and we know very little about the percussion instruments.

The vièle was the principal instrument with which the jongleur

was pictured. There is no doubt that instruments could accompany and

double the voice or voices and also that they could play all the voices

of a song as a purely instrumental composition, as was authorized by

Guillaume de Machaut himself for his ballads. The instruments used on

this record are as follows:

"I cannot too much compare my Lady

The

dance in the Middle Ages was as much a fundamental activity in the

market place and at secular festivals as it was in the church: danses macabres,

pictured in sometimes very realistic tableaux, Saint Vitus' dances,

etc. There was no event which was not an occasion, in both noble and

humble dwellings, to express one's joy, one's sadness or one's fear by

gestures. The French theoretician Jean de Grouchy: in a treatise written

around 1300 describing the different genres of secular music, declared that there were

three instrumental dance forms: the estampie, the ductia and the nota;

their compositional principles were all the same

(several different sections or puncta, which were each repeated).

In general, the estampie possessed a greater number of puncta than the ductia or the nota,

whose rhythms were accentuated by a percussion instrument. Note

repetitions, leaps of a fourth or a fifth and very short ornaments were

characteristic of the estampie Royale (French) and the Italian istampita "Ghaetta,"

named after the port city of Gaete. Clearly the nota had a more rugged character,

with a simple four-square melody. The famous estampie "Kalenda maya"

of the troubador-knight Raimbault de Vaqueiras (d.1207), vassal of

Boniface de Montferrat, was improvised, it is said, on the melody of an

instrumental estampie that two jongleurs had just played

on the vièle: its melody is languorous, supple and unhurried like the

Provençal poetry of Bernart de Ventadorn, without doubt the most

melancholy and inspired of the troubadours.

The upper voice includes the following words: Elena Polonska and Gérard Fleury.

LA CAMERATA

Elena Polonska, medieval harp, Iris harp, percussion

Nives Poli-Rapp, lute, psaltery & percussion

Steve Rosenberg, recorders, schalmey

Jacques Manzone, viéle, rebec, percussion

Daniel Dossmann, zarb, tambourine

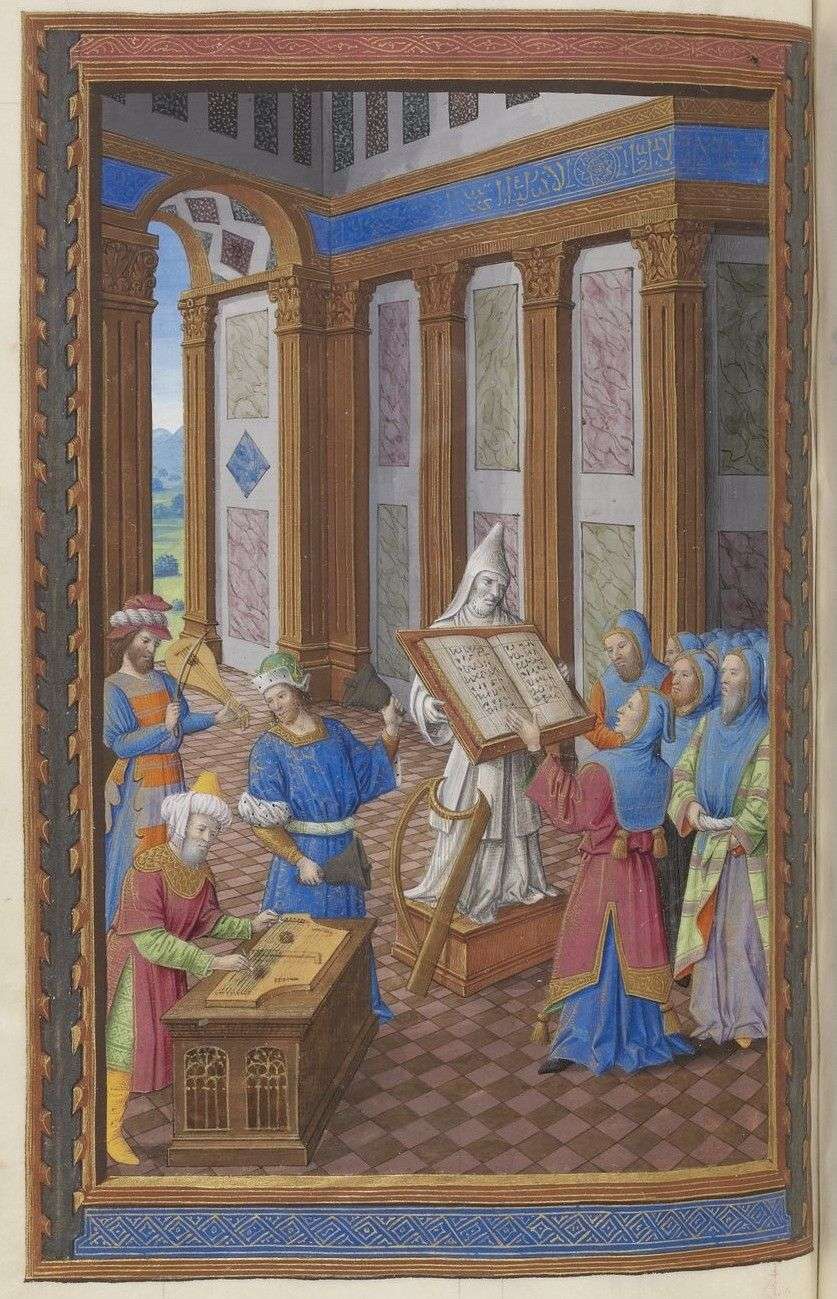

COVER ILLUSTRATION:

Diurnal of Rene II de Lorraine (15th C. - A Chorus of Musicians in the Temple, Paris)

Photo: SNARK International

℗ 1974 VOX PRODUCTIONS, New York

.jpg)

1. The vièle de bras (from the

Provençal word "viola" or "viula") is a bowed instrument with a

soundbox in the shape of a slightly elongated oval, sometimes slightly

notched, with a flat bottom and 3 to 5 strings.

2. The rebec (from the Arabic "rebab"), a small bowed instrument with a slightly rounded tapering body and 3 strings.

3. The recorder family or flauti dolci.

4. The soprano schalmey is a member of the double reed family of instruments, ancestors of the oboe..

5. The psaltery, a plucked instrument with strings stretched over a soundboard and played by one or two plectra.

6. The lute

is probably an instrument of Arabic origin. with an angled fingerboard,

doubled strings, a soundboard pierced by a rose and a curved body.

According to the "Cantigas de Santa Maria," it appeared in the 10 th

century.

7. The zarb, a Persian percussion instrument, as well as little cymbals and tambourines.

8.

The harp, the most ancient of all instruments along with the flute, in

its Medieval version of metal strings and a form resembling the harp of

the Irish king Brian Boru (12th century), and its Irish version, with

gut strings. Very much in fashion among the Egyptians, the Hebrews and

the Greeks (even though it was proscribed in the time of Pericles, since

the philosophers had declared its voluptuous and sensual character to

be dangerous to morality), its appearance in Europe is attributed to the

Scandinavians, Teutons and Celts. Already by the 12th century, the

refinement of construction of the Irish harp was extreme (the number of

strings varied from 7 to 30), and harpists, such as the famous Blondel

de Nesle, harpist to Richard the Lion-Hearted, enjoyed great favor. The

harp not only inspired the plastic arts, but also gave birth to a whole

school of symbolic poetry. Dante mentions it in his "Paradise" and

Guillaume de Machaut mentions it in his more worldly evocations, such as

in the following poem:

To the harp, with its lovely body adorned

With twenty-five strings, as was the harp

Which King David many times played."

The polyphonic genre

(in 2 voices) of the Italian "ballata" (derived from the French

"virelai") is represented by a composition of Giovanni da Florentia

(d.1351) and also by a piece by the specialist of this genre, Francesco

Landino (d.1397), known as the "Cieco degli organi" (The Blind

Organist). He was one of the most remarkable masters of the Ars Nova,

who composed more than 140 ballads in 3 voices including ones such as

the example on this recording, written in an expressive style, with

great rhythmic subtlety and full of sentimental sweetness (the text

begins with "Nel mio dolce sospir . . ."). The term "madrigal" is

derived from the expression cantus materialis (as opposed to the cantus spiritualis)

and designates a song whose aim is to entertain and amuse during

periods of relaxation: the one recorded here is by Magister Piero, a

composer in the service of the Visconti family in Milan and the

Scaglieri family in Verona; he is probably the inventor of the canonic

madrigal and his style is distinguished by the abundant use of unisons,

parallel fifths and octaves.

A chanson de toile (lit.

"linen song"), with a monotonous litany-like character such as women

used to sing while weaving, and three other anonymous songs ("Le

Rossignol," "En mai la rousée," and the beautiful complaint [b]"Trop penser

me font amours") lead us to the subject of the trouveurs, a general term designating the troubadours

of the South and the trouvères of the North.

Let us remember that the profession of trouveur,

which is to say a highly esteemed composer-poet, was clearly differentiated from that of jongleur,

the wandering entertainer who was later to become the minstrel-musician

with a permanent position at Court or in the retinue of a noble.The

troubadour Bernart de Ventadorn and the trouvère Thibault IV de

Champagne, the very learned and cultivated king of Navarre (d.1253 at

Pampelune) reveal to us the secrets of their art, the former in the

melody whose languorous character we have already emphasized, the latter

in a sort of free-style lamento ("Pour ce se d'amer me dueil"), although the trouvère melodies

were usually more rhythmically strict.

To these we must add two others: Blonde! de Nesle with his melancholy song "A l'entrée de l'esté"

and Gauthier de Coincy, a monk and prior at Saint Médard de Soissons

and the author of the "Miracles de Notre Dame," "an immense cycle of

stories in verse which display his emotional, ardent and almost sickly

temperament" (Jacques Chailley), from which is excerpted the song "Ma vièle".

The king of Castille and León, Alfonso X "The Wise" (1221-1284), a

great patron of the arts, imitated Gauthier de Coincy in his "Cántigas de Santa Maria,"

a collection of 428 religious poems dedicated to the Virgin, some of which are of his own composition.

Oswald von Wolkenstein (d.1445) and the Deutsches Lied "Elend du hast mich umfangen"

follows the tradition of the German Minnesänger, whose style recalls

that of the French Ars Nova which first appeared around 1150 under the

influence of the Provençal troubadours who it will be recalled,

travelled a great deal.

After a clausolae, a kind of polyphonic composition built on a short excerpt from a song ("Hace Dies"

in this case) and treated in the concise style of Pérotin (the greatest

of the Notre Dame School composers), there follow two interesting

examples of the "profane" motet of the 12th century, "Flos filius" ' and "Pucelete".

The compositional procedure is simple: a portion of an organum

is chosen where the tenor voice (written in long rhythmic values) is

fastest, or where its rhythm is closest to that of the other voices, the

words being in close rapport with the tenor as to their meaning.

However, as this genre evolved, the words became secular and no

longer had any relation to the words of the tenor part, as in the case

of the following:

"Pucelete bele et avenant joliette" (Beautiful and lovely young girl)

The middle voice recites:

"Je languis des maus d'amour ..." (I languish front the pain of love ...

The tenor (in long rhythmic values):

"Domino" (to God)

Edited and translated by PETER TRACTON