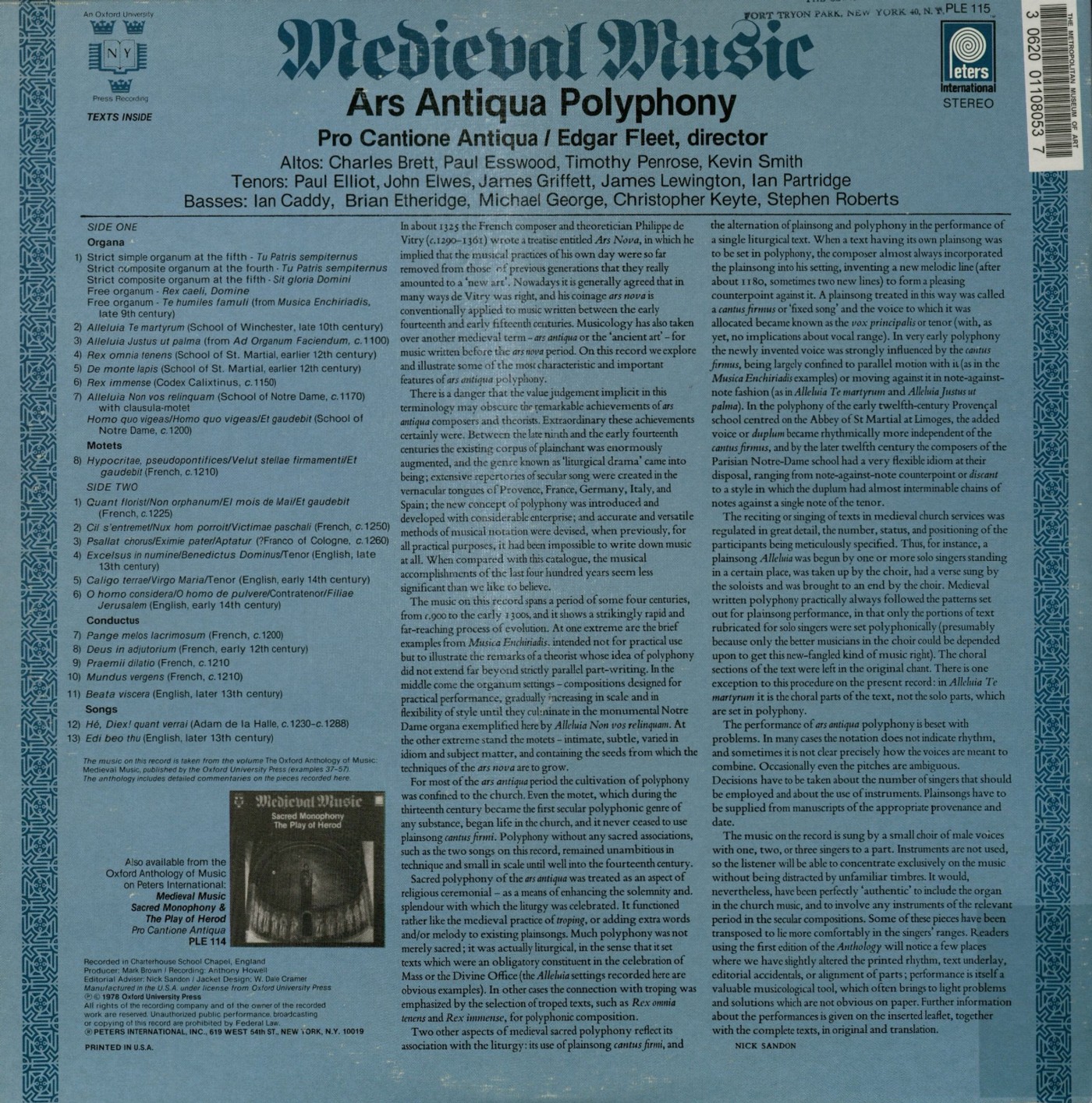

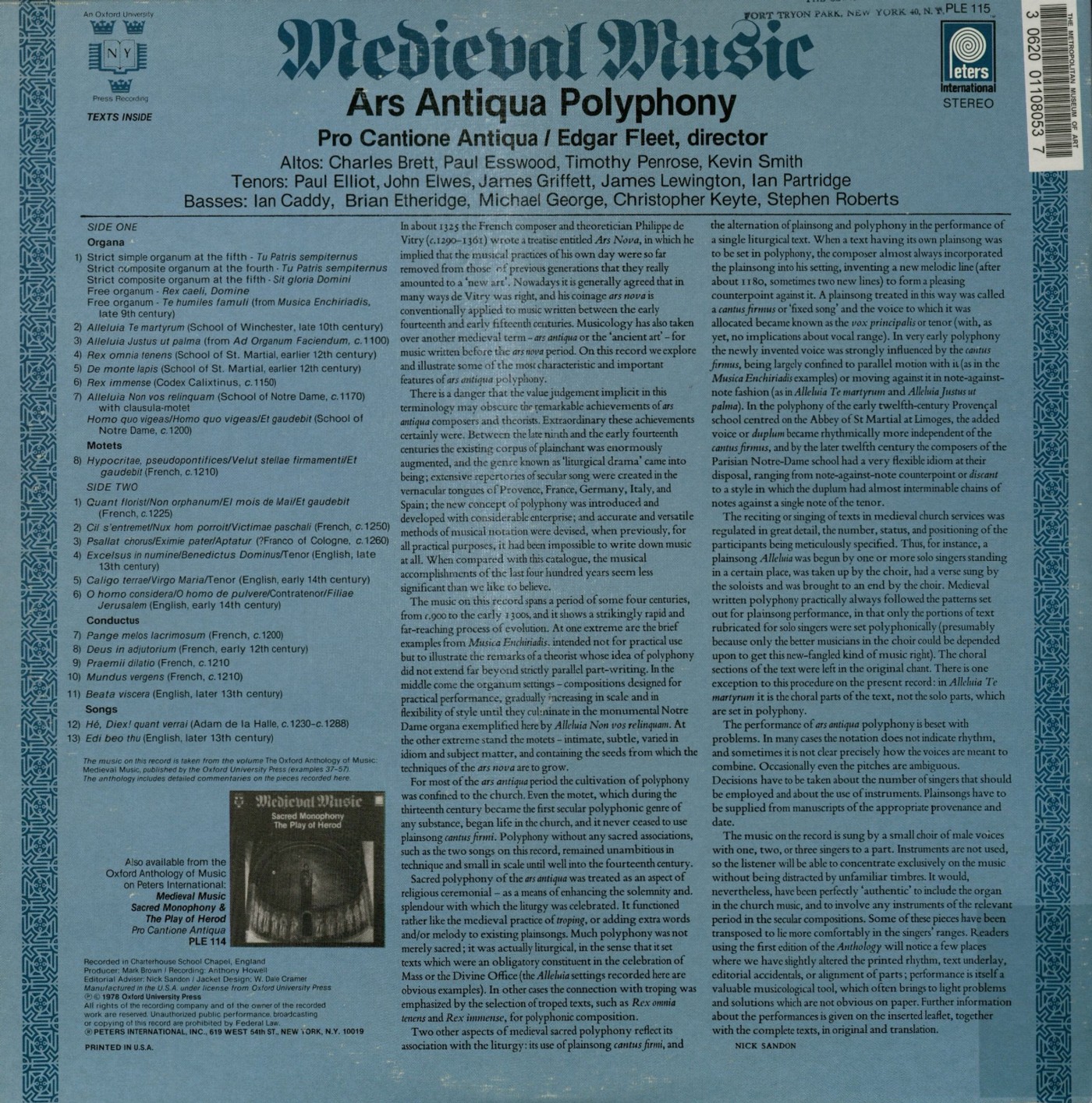

Ars Antiqua Polyphony

/ Pro Cantione Antiqua, Edgar Fleet

The Oxford Anthology of Music: Medieval Music

medieval.org |

worldcat.org

Oxford University Press OUP 164 | Peters International, PLE 115

[50:09]

SIDE ONE

[24:10]

Organa

1. [1:36]

Tu Patris sempiternus strict simple organum at the fifth

Tu Patris sempiternus strict composite organum at the fourth

Sit gloria Domini strict composite organum at the fifth

Rex caeli, Domine free organum

Te humiles famuli free organum · from Musica Enchiriadis, late 9th century

2. Alleluia. Te martyrum [1:54] School of Winchester, late 10th century

3. Alleluia. Justus ut palma [2:38] from Ad Organum Faciendum, c.1100

4. Rex omnia tenens [2:41] School of St. Martial, earlier 12th century

5. De monte lapis [4:21] School of St. Martial, earlier 12th century

6. Rex immense [1:08] Codex Calixtinus, c.1150

cc 108

7. [7:23]

Alleluia. Non vos relinquam · School of Notre Dame, c.1170 with

clausula-motet Homo quo vigeas | Homo quo vigeas | Et gaudebit · School of Notre Dame, c.1200

Motets

8. Hypocritae, pseudopontifices | Velut stellae firmamenti | Et gaudebit [2:29] French. c.1210

SIDE TWO

[22:58]

1. [3:10]

Cuant florist | Non orphanum | Et gaudebit · French, c.1225

Cuant florist | El mois de Mai | Et gaudebit · French, c.1225

2. Cil s'entremet | Nux hom porroit | Victimae paschali [1:05] French, c.1250

3. Psallat chorus | Eximie pater | Aptatur [1:12] ? FRANCO of COLOGNE, c.1260

4. Excelsus in numine | Benedictus Dominus | Tenor [1:51] English, late 13th century

5. Caligo terrae | Virgo Maria | Tenor [3:38] English, early 14th century

6. O homo consideral | O homo de pulvere | Contratenor | Filiae Jerusalem [1:56] English. early 14th century

Conductus

7. Pange melos lacrimosum [2:41] French, c.1200

8. Deus in adjutorium [2:41] French, early 12th century

9. Praemii dilatio [2:41] French. c.1210

10. Mundus vergens [2:41] French, c.1210

11. Beata viscera [2:41] English, later 13th century

Songs

12. He, Diex! quant venal [2:41] Adam de la Halle, c.1230-c.1288

13. Edi beo thu [2:41] English, later 13th century

Pro Cantione Antigua

Edgar Fleet, director

Altos: Charles Brett, Paul Esswood, Timothy Penrose, Kevin Smith

Tenors: Paul Elliot, John Elwes, James Griffett, James Lewington, Ian Partridge

Basses: Ian Caddy, Brian Etheridge, Michael George, Christopher Keyte, Stephen Roberts

The music on this record is taken from the volume The Oxford Anthology

of Music: Medieval Music,

published by the Oxford University Press

(examples 37-57).

The anthology includes detailed commentaries on the pieces recorded here.

An Oxford University Press Recording

Recorded in Charterhouse School Chapel, England

Producer: Mark Brown | Recording: Anthony Howell

Editorial Adviser: Nick Sandon

Jacket Design: W. Dale Cramer

© & ℗ 1978 Oxford University Press

® Peters International, Inc.

In about 1325 the French composer and theoretician Philippe de Vitry (c.1294)-1361 ) wrote a treatise entitled Ars Nova, in which he implied that the musical practices of his own day were so far removed from those of previous generations that they really amounted to a 'new art'. Nowadays it is generally agreed that in many ways de Vitry was right, and his coinage ars nova is conventionally applied to music written between the early fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. Musicology has also taken over another medieval term - ars antiqua or the 'ancient art' - for music written before the ars nova period. On this record we explore and illustrate some of the most characteristic and important features of ars antiqua polyphony.

There is a danger that the value judgement implicit in this terminology may obscure the remarkable achievements of ars antiqua composers and theorists. Extraordinary these achievements certainly were. Between the late ninth and the early fourteenth centuries the existing corpus of plainchant was enormously augmented, and the genre known as 'liturgical drama' came into being; extensive repertories of secular song were created in the vernacular tongues of Provence, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain; the new concept of polyphony was introduced and developed with coasiderable enterprise; and accurate and versatile methods of musical notation were devised, when previously, for all practical purposes, it had been impossible to write down music at all. When compared with this catalogue, the musical accomplishments of the last four hundred years seem less significant than we like to believe.

The music on this record spans a period of some four centuries, from c.900 to the early 1300s. and it shows a strikingly rapid and far-reaching process of evolution. At one extreme are the brief examples from Musica Enchiriadis, intended not for practical use but to illustrate the remarks of a theorist whose idea of polyphony did not extend far beyond strictly parallel part-writing. In the middle come the organurn settings - compositions designed for practical performance, gradually increasing in scale and in flexibility of style until they culminate in the monumental Notre Dame organa exemplified here by Alleluia Non vos relinquant. At the other extreme stand the motets - intimate, subtle, varied in idiom and subject matter, and containing the seeds from which the techniques of the ars nova are to grow.

For most of the ars antiqua period the cultivation of polyphony was confined to the church. Even the motet, which during the thirteenth century became the first secular polyphonic genre of any substance, began life in the church, and it never ceased to use plainsong cantus firmi. Polyphony without any sacred associations, such as the two songs on this record, remained unambitious in technique and small in scale until well into the fourteenth century.

Sacred polyphony of the ars antiqua was treated as an aspect of religious ceremonial - as a means of enhancing the solemnity and splendour with which the liturgy was celebrated. It functioned rather like the medieval practice of troping, or adding extra words and/or melody to existing plainsongs. Much polyphony was not merely sacred; it was actually liturgical, in the sense that it set texts which were an obligatory constituent in the celebration of Mass or the Divine Office (the Alleiuia settings recorded here are obvious examples). In other cases the connection with troping was emphasized by the selection of troped texts, such as Rex omnia tenens and Rex immense, for polyphonic composition.

Two other aspects of medieval sacred polyphony reflect its association with the liturgy: its use of plainsong cantus firmi, and the alternation of plainsong and polyphony in the performance of a single liturgical text. When a text having its own plainsong was to be set in polyphony, the composer almost always incorporated the plainsong into his setting, inventing a new melodic line (after about 1180, sometimes two new lines) to form a pleasing counterpoint against it. A plainsong treated in this way was called a cantus firmus or 'fixed song' and the voice to which it was allocated became known as the vox principalis or tenor (with, as yet, no implications about vocal range). In very early polyphony the newly invented voice was strongly influenced by the cantus firmus, being largely confined to parallel motion with it (as in the Musica Enchiriadis examples) or moving against it in note-against note fashion (as in Alleluia Te martyrum and Alleluia Justus ut palma). In the polyphony of the early twelfth-century Provenšal school centred on the Abbey of St Martial at Limoges, the added voice or duplum became rhythmically more independent of the cantus firmus, and by the later twelfth century the composers of the Parisian Notre-Dame school had a very flexible idiom at their disposal, ranging from note-against-note counterpoint or discant to a style in which the duplum had almost interminable chains of notes against a single note of the tenor.

The reciting or singing of texts in medieval church services was regulated in great detail, the number, status, and positioning of the participants being meticulously specified. Thus, for instance, a plainsong Alleluia was begun by one or more solo singers standing in a certain place, was taken up by the choir, had a verse sung by the soloists and was brought to an end by the choir. Medieval written polyphony practically always followed the patterns set out for plainsong performance, in that only the portions of text rubricated for solo singers were set polyphonically (presumably because only the better musicians in the choir could be depended upon to get this new-fangled kind of music right). The choral sections of the text were left in the original chant. There is one exception to this procedure on the present record: in Alleluia Te martyrum it is the choral parts of the text, not the solo parts, which are set in polyphony.

The performance of ars antiqua polyphony is beset with problems. In many cases the notation does not indicate rhythm, and sometimes it is not clear precisely how the voices are meant to combine. Occasionally even the pitches are ambiguous. Decisions have to be taken about the number of singers that should be employed and about the use of instrurnents. Plainsongs have to be supplied from manuscripts of the appropriate provenance and date.

The music on the record is sung by a small choir of male voices with one, two, or three singers to a part. Instruments are not used, so the listener will be able to concentrate exclusively on the music without being distracted by unfamiliar timbres. It would, nevertheless, have been perfectly 'authentic' to include the organ in the church music, and to involve any instruments of the relevant period in the secular compositions. Some of these pieces have been transposed to lie more comfortably in the singers' ranges. Readers using the first edition of the Anthology will notice a few places where we have slightly altered the printed rhythm, text underlay, editorial accidentals, or alignment of parts; performance is itself a valuable musicological tool, which often brings to light problems and solutions which are not obvious on paper. Further information about the performances is given on the inserted leaflet, together with the complete texts, in original and translation.