The achievements of English composers during the Middle Ages and

Renaissance were unsurpassed anywhere in Europe, though today they

still tend to be undervalued. The series Ars Britannica

explores this repertory and illustrates some of its treasures: it aims

to show the essential vitality and continuity of the English musical

tradition.

Old Hall Manuscript

Music for the House of Lancaster

The compositions on this record demonstrate all of the major genres,

techniques and styles cultivated by English composers during the early

15th century. They also evince the varied nature of English sacred

polyphony during this period.

The early 1400s saw several changes of direction in English politics

and diplomacy. With the deposition of Richard II (1367-1400) in 1399

and the accession of Henry IV (1367-1413) the direct Plantagenet line

was supplanted by the House of Lancaster. The new king was talented and

cultured, with an uncommon skill in and love for music. He passed on

many of his qualities to his four sons, the future Henry V (1387-1422),

Thomas Duke of Clarence (1388-1421), John Duke of Bedford (1389-1435)

and Humfrey Duke of Gloucester (1391-1447). He reorganised the royal

household chapel (the institution which performed the daily devotions

of the monarch and his court) to allow more emphasis on the musical

aspects of the worship; Henry V subsequently augmented its musical

personnel. Clarence, Bedford and Gloucester employed in their own

chapels some of the foremost composers of the day. While some of this

may reflect the conventional desire to advertise wealth and power

through patronage, it may well indicate a real piety and an attempt to

win divine approval for the upstart royal dynasty; it may also have

been a regal counter to the contemporary Lollard movement, with its

hostility to sacred music and liturgical elaboration.

The early Lancastrians pursued an active and at time aggressive foreign

policy. By sending English representatives to the Councils of Pisa

(1409) and Constance (1414-1418) they showed their concern for the

welfare of Christendom. Henry V's revival of the English claim to the

French crown enjoyed initial success at the battle of Agincourt (1415)

and culminated in the Treaty of Troyes (1420) by which Charles VI

recognised Henry as his heir. The early conquests and later defence

against the French counter-attack kept the royal dukes and other

English aristocrats in France as military commanders, often for months

or years at a time. English prelates and the lay nobility habitually

took their private chapels with them on their travels, and it was

probably by hearing these chapel choirs that foreign listeners became

acquainted with English music during the 1410s and 1420s. The

distinctive English sound — particularly its consonance, its full

sonority and its smoothly flowing rhythms and melodies — made a

strong impact, initiating a demand for English music which lasted until

the middle of the century and influencing the styles of Dufay, Binchois

and their colleagues.

Apart from the pieces by Dunstable, these compositions survive in the

Old Hall manuscript (London, British Library, Add, MS. 57950). One of

the few remaining insular musical sources of the period, it probably

belonged to the household chapel of Thomas, Duke of Clarence,

apparently passing to the royal household chapel after his death. It is

a collection of polyphonic settings of the Gloria, Credo, Sanctus and

Agnus, with some interpolated isorhythmic motets and votive antiphons;

most of the works are English, although there are a few pieces by

Italian and French composers. Lionel Power, Informator in Clarence's

chapel, figures prominently in the collection; little is known about

his later career although he may have become Master of the Lady Chapel

choir at Canterbury Cathedral in about 1438 (he died at Canterbury in

1445). Three of the other composers on this record were members of the

royal household chapel: John Cooke (d. 1419) and Thomas Damett

(d.-1437) from about 1413 and Robert Chirbury (d. 1454) from 1420.

Pycard was a singer in John of Gaunt's chapel in the 1390s; of Forest

nothing is known. John Dunstable may have sung in the chapel of John,

Duke of Bedford; otherwise his career is obscure. These four

compositions by him are preserved in continental sources.

Chirbury's Agnus typifies the simpler kind of Mass movement in

Old Hall, with three voices moving mainly in note-against-note fashion;

the opening chromaticism is indicated in the manuscript. Pycard's Gloria

is more elaborate; three lively voices (two of them in canon) sing the

text above two more sustained supporting lines. The animated rhythms,

canonic writing and closing hocket (the exchange of tiny motives

between the voices) attest Pycard's French training. French influence

is also evident in Power's ambitious Credo, with its parlando

passages, syncopation and ornamental dissonance; the alternation of

duet and tutti is, however, characteristically English.

Until the 1420s and 1430s, when it was supplanted by the cyclic Mass

(itself an English invention) the isorhythmic motet was the most

respected and imposing musical genre. Based on a plainsong tenor cast

in a repeating rhythmic pattern, and having two or more upper voices

usually singing different texts, its origins lay in the Parisian motet

of the early 1200s. Continental composers often gave it a secular and

ceremonial function, but in England its usage remained almost always

sacred, commonly as part of the cults of popular saints. Cooke's Alma

proles is the nearest English approach to the political motet;

invoking the protection of the Virgin and St. George against England's

enemies, it may refer to the renewal of hostilities between England and

France. Dunstable's Gaude virgo salutata (to the Virgin) and Albanus

roseo rutilat (to St. Alban) are more modern in style than Alma

proles, the lines being smoother and the dissonances more carefully

controlled; the former also adds a fourth part to the customary

three-part texture.

The votive antiphon was a non-liturgical but devotional text in Latin,

in honour of a saint or a religious theme, often sung after Compline at

the altar of the saint concerned. Damett's Salve porta and

Forest's Qualis est dilectus are addressed to the Virgin, by

far the most popular dedicatee of such pieces: the former is modest in

scale and simple in style whereas the latter is extended and

enterprising in its musical contrasts. Antiphons of the Holy Cross are

rare; Dunstable's Crux fidelis and O crux gloriosa

exemplify the mature English style of the 1420s, employing variations

of texture and metre in a consonant and mellifluous idiom.

Since there is no evidence that any instrument apart from the organ

participated in the performance of sacred music at this time, these

works are performed by voices alone, with an organ doubling some of the

sustained textless lines.

Madrigals and Lute Songs (Ayres)

Secular vocal music under Elizabeth I and James I

These two records of madrigals and ayres illustrate two aspects of a

native tradition of secular vocal music which extended back to the

earlier 16th century. They also show how certain composers reacted to

the stimulus produced by greater exposure to Italian and French music.

The madrigal was essentially a polyphonic and entirely vocal genre

which employed musical contrasts and expressive devices to reflect the

changing moods and imagery of its text. The ayre or part-song was more

homophonic, with the melody in the top voice and a strongly harmonic

bass, and it made little or no attempt to underline in the music the

nuances of the poem. Distinctions between the madrigal and ayre were

not totally rigid, however: some ayres (such as Dowland's Where sin

sore wounding from A Pilgrimes Solace, 1612 and I must

complain from The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Aires,

1603) are unusually polyphonic, while many of the lighter madrigals

(such af Weelkes' Some men desire spouses from or Phantasticke

Spirites, 1608) are almost entirely chordal. Nevertheless the

stylistic division was real, and composers worded their title pages

with care.

Like the Italian frottola and the mid-16th century French chanson, the

ayre could be performed either by a vocal group or by a solo singer

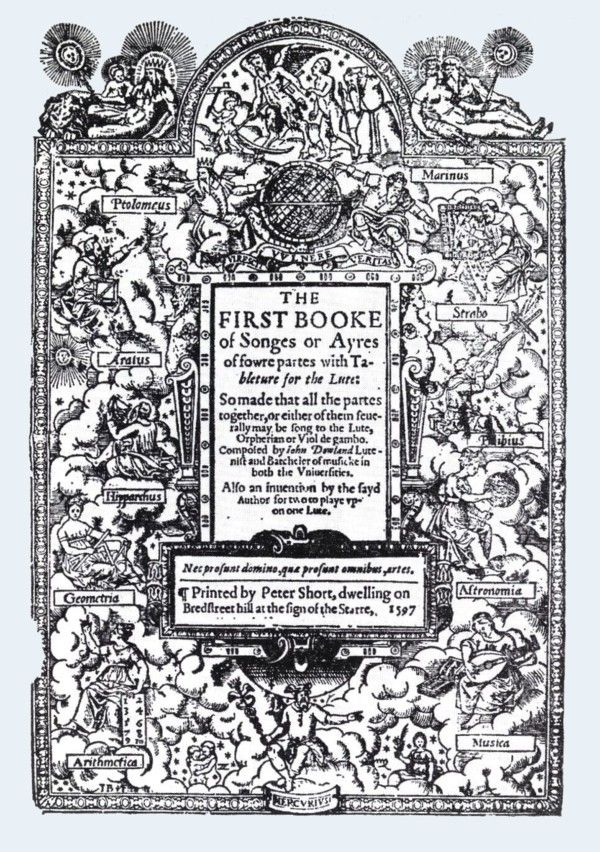

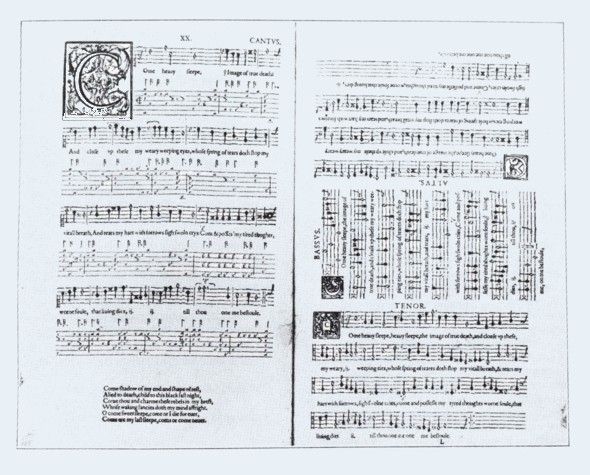

accompanied by an instrument (often a lute): John Dowland entitled his

1597 collection "The First Booke of Songs or Ayres of fowre parts with

Tableture for the Lute: So made that all the partes together, or either

of them severally may be song to the Lute, Orpherian or Viol de gambo".

Today we are so used to hearing these sung as lute-songs that we need

to guard against the assumption that this is the preferable method of

performance, whereas it is actually only one possibility. In the

interpretations on this record a cappella performance alternates with a

vocal ensemble accompanied by lute and viol, and with a solo singer

accompanied by the lute.

After its splendid flowering at the courts of Henry VII and the young

Henry VIII the secular song seems to have withered. Most of the few

songs by mid-century composers such as Tallis, Sheppard and Tye which

have survived set sententious poems either in a severely imitative

style or in simple harmonisations like those used for setting metrical

psalms. The poetry is generally pedestrian, relying excessively on long

lines and alliteration, as in Tallis' When shall my sorrowful

sighing slake.

It is understandable that the Elizabethan taste for Italian literature,

art and architecture should have extended also to music, because the

Italian madrigal offered in a mature form qualities which were either

absent from or only embryonic in the English song — a polished

and versatile contrapuntal idiom wedded to sophisticated poetry Which

had already amassed a stock of characteristic situations and images.

Printed editions of Italian madrigals were being imported into England

in the 1570s and 1580s, and Nicholas Yonge's seminal publication Musica

Transalpina (1588), an anthology of Italian madrigals with the

texts translated into English, was an avowed attempt to cater for a

growing market. The strength of the demand is indicated by the

appearance of four more Italian anthologies and some fifteen editions

by native composers such as Thomas Morley, Thomas Weelkes and John

Wilbye, all before 1600. The spate of madrigal prints gradually

decreased during the early 1600s (Pilkington's Second Set of

1624 was virtually the last significant publication); the fact that

increasing numbers of ayres were printed during the same period

suggests that the public's taste was changing.

The works in the anthologies and the compositions of the English

madrigalists themselves show a clear preference for the more

lighthearted type, often in a pastoral setting (as in Hark, jolly

shepherds from Morley's Book I of 1594). The musical intensity and

highly-charged emotionalism of Wert or Rore was generally not to the

English taste, although Ward could create an atmosphere of unusual

gravity (as in Retire, my troubled soul and O my thoughts

surcease from his Book l of 1613). With a few exceptions

English composers did not attempt the chromatic experiments of the

Italian madrigal; when they did, as in Come, woeful Orpheus

from Byrd's Psalmes, Songs and Sonnets of 1611, there is often

a sense of stylistic disunity (though in this case it is possible that

Byrd was parodying the style). The quality of the English madrigal

really lies in the fluency and charm with which elegantly-turned poetry

is set. The unobtrusive perfection of the finest examples, such as

Weelkes' Those sweet delightful lilies and Wilbye's Lady,

when I behold, makes exaggerated claims unnecessary.

Traditional traits are more evident in the ayre than in the madrigal.

The poetry tends to be more substantial, and something of the earlier

predilection for moralising or devotional texts remains (see for

example Campion's Never weather-beaten sail and Jack and Jone,

both from his First Booke of Ayres of c. 1613). Even the

simplest ayres, such as Since first I saw your face and There

is a lady (both from Thomas Ford's Musicke of Sundrie Kindes

of 1607) are pithy in a way which belies their apparent artlessness.

The more ambitious pieces, like Dowland's I must complain,

strike the listener with unusual force, partly through the solemnity of

their contrapuntal style.