medieval.org

Christophorus CHR 77376

2013

medieval.org

Christophorus CHR 77376

2013

De Sancta Maria

1. [10:07]

Antiphon. O splendissima gemma

& Psalm 121, Laetatus sum

De undecimus milibus virginum

2. Antiphon. Aer enim volat (instr.) [4:07]

De Sancta Maria

3. Responsorium. Ave Maria, o auctrix vitae [8:15]

De Prophetis et Patriarchis

4. Antiphon. O spectabiles viri [6:35]

5. Improvisation auf der Streichleier [2:43]

De Spiritu Sancto

6. [7:37]

Antiphon. Caritas habundat

& Psalm 109, Dixit dominus

7. Antiphon. Laus Trinitati [2:07]

8. Hymnus. O ignee Spiritus [8:15]

De Apostolis

9. Responsorium. O lucidissima Apostolorum turba [4:49]

10. Responsorium. O cho(h)ors militiae floris [3:04]

De Sancto Disibodo

11. Responsorium. O viriditas digiti Dei [5:16]

12. Antiphon. O magne Pater [3:02]

Burkard Wehner

Hildegard of Bingen – The Visionary and Her Works Burkard Wehner

PER-SONAT

Sabine Lutzenberger Sopran & Glocken / soprano & bells

Baptiste Romain mittelalterliche Fideln & Streichleier / medieval vielles & bowed lyre

Unser Dank gilt dem Benediktinerstift Sankt Stephan in Augsburg für die liebenswerte Unterstützung

Executive producer: Joachim Berenbold

Recording: 23-26 November 2012, Benediktinerstift Sankt Stephan, Augsburg

Recording producer & digital editing: Eckhard Glauche

Cover

picture: Der Leuchtende, Scivias-Codex (vor 1179, verschollen, nach

Faksimile),

Benediktinerabtei St. Hildegard, Rüdesheim

Artist photos:

Feiko Koster (p. 7) · Ellen Schmaus (p. 15)

Layout: Joachim Berenbold

Translations: David Babcock (English) · Sylvie Coquillat

Ⓟ + © 2013 note 1 music gmbh, Heidelberg, Germany

Hildegard von Bingen – die Visionärin und ihre Werke

Hildegard

von Bingen — hinter diesem berühmten und klangvollen Namen verbirgt sich

eine der eigenwilligsten Persönlichkeiten des 12. Jahrhunderts. Nachdem

sie als zehntes Kind von ihren adeligen Eltern Hildebert und Mechthild

im Alter von acht Jahren dem Benediktinerkloster am Disibodenberg als

‚oblata’ (Gabe an Gott für ein geistliches Leben) übergeben wird,

erfährt sie dort durch die acht Jahre ältere Nonne Jutta von Sponheim

ihre religiöse Erziehung und eine umfassende Bildung.

Am 1.

November 1112 wird sie zusammen mit ihrer Lehrmeisterin nach ihrem

Willen in einen Turm im Kloster Disibodenberg eingeschlossen, das seit

1108 von Benediktinermönchen bewohnt wird. Nach Jahren des asketischen

Lebens, die durch visionäre Bilder begleitet werden, ist aus der Klause

ein Frauenkloster geworden und Hildegard wird nach dem Tod Juttas 1136

zur Magistra der versammelten Schülerinnen gewählt.

Mit enormem

Durchsetzungsvermögen und gegen viele Widerstände gründet und leitet sie

das Kloster am Rupertsberg nahe Bingen am Rhein. In erster Linie werden

dort junge adlige Frauen aufgenommen, die eine nicht unbeträchtliche

Mitgift mit ins Kloster einbringen, was für Unmut innerhalb des Klerus

und der Bevölkerung sorgt. Schon bald gibt es Gerüchte um die Nonnen,

die angeblich mit offenen Haaren und geschmückt — wie echte adelige

Bräute — im Kloster auf ganz eigene Art die Liturgie zelebrieren.

Hildegard

wird trotz aller Anfeindungen Mahnerin und Trösterin in ihrer Zeit.

Korrespondenzpartner zu Hildegards Lebenszeit sind Könige, Fürsten,

Bischöfe, Äbte und Äbtissinnen, in deren Klöstern Unfrieden herrscht.

Auch mit dem überaus einflussreichen Zisterziensermönch Bernhard von

Clairvaux ist ein Briefwechsel erhalten geblieben und er ist es, der

Hildegards Aussagen und Visionen gegenüber Papst Eugen III. 1147/48 auf

der Trierer Synode verteidigt und Hildegard ermutigt, sie aufzuzeichnen.

Visionen und Visionsliteratur stand damals oft in dem Verdacht,

unautorisiertes häretisches und der Kirche schädigendes Gedankengut zu

verbreiten, aber gerade der Segen dieses Papstes trägt noch mehr zu

Hildegards Popularität bei. Nach längeren Predigt- und Visitations

reisen kehrt Hildegard schließlich 1171 in ihr Mutterkloster zurück und

stirbt 81-jährig am 17. September 1179.

Die von vielen Seiten

erwartete Heiligsprechung Hildegards nach ihrem Tod bleibt aus und

erfolgt auch in den nachfolgenden Jahrhunderten nicht. Allerdings wird

sie auf Initiative von Papst Benedikt XVI. am 10. Mai 2012 in das

Heiligenverzeichnis der Gesamtkirche aufgenommen und kann damit auch

ohne formale Heiligsprechung in der ganzen Weltkirche als Heilige

verehrt werden.

Die Nachwelt würdigt das Wirken von Hildegard dauerhaft, was bereits ein Zitat aus der Schedelschen Weltchronik

von 1493 belegt: Sie „het aus goettlicher kraft die gnad, das sie

(wiewol sie ein layin und ungelert was) offt wunderperlich imm schlaff

entzugt, lernet nicht allain latein reden sunder auch schreyben unnd

tichten, also das sie ettliche buecher christenlicher lere machet.“

In ihrem ersten und bekanntesten Werk Scivias

(Wisse die Wege) legt die inzwischen 42-jährige Hildegard in 26

Bild-Visionen die Heilsgeschichte der Welt aus — von der Schöpfung bis

zum Ende der Zeit. Hildegard schildert darin den mystischen Weg der

Seele (anima) hin zum Heil durch innere Betrachtungen und Leiden.

Die Einheit der Kirche mit den helfenden Kräften der Propheten,

Aposteln und Heiligen und der Kampf gegen das Böse, das in personaler

oder verkleideter Gestalt des Teufels auftritt, sind die zentralen

Themen Hildegards. Jede einzelne Seele ist dabei ständig in Gefahr, der

gläubigen Schar entrissen zu werden.

Die Handschrift

Der

Codex aus Dendermonde entsteht noch zu Lebzeiten Hildegards um 1175 und

kommt als Geschenk Hildegards in das Zisterzienserkloster

Villers-la-Ville, im heutigen Belgien gelegen, einer Tochtergründung von

Clairvaux durch den Heiligen Bernhard und Godfrey III., Herzog von

Brabant. Sie enthält Hildegards berühmte Liedersammlung Symphonia harmoniae caelestium relevationum mit 56 Liedern, die im Stundengebet und in der Messe gesungen werden.

Sabine

Lutzenberger und Baptiste Romain musizieren dabei aus Reproduktionen

der Originalhandschrift und kommen so zu einer ganz eigenen,

tiefgreifenden und subtilen Interpretation, die viele Eigenheiten der

Notation respektiert.

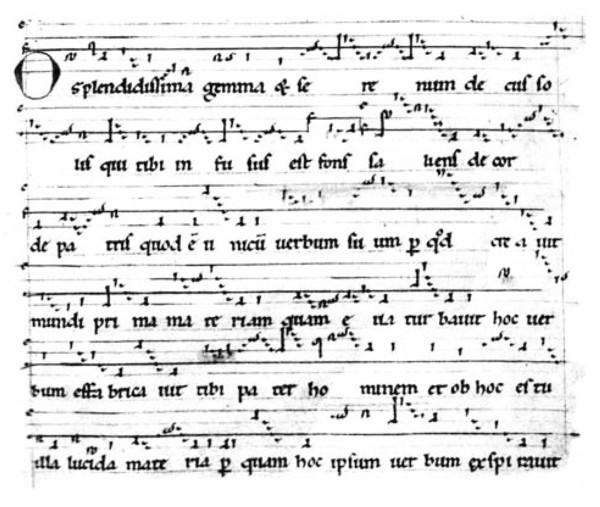

Die Lieder

Die Lieder

sind durch ein komplexes System von graphischen Notenzeichen (Neumen) in

einer frühen Form der deutschen Hufnagelnotation in einem

5-Linien-System notiert. Die C- und F-Schlüssel geben eindeutige

Indikationen für die Tonhöhen und zur besseren Lesbarkeit ist die

C-Linie gelb und die F-Linie rot gefärbt. Dadurch werden die

Halbtonschritte c-h und f-e verdeutlicht und graphisch sichtbar gemacht.

Die vielen verschiedenen Neumenzeichen beinhalten neben Einzelnoten

auch Notenverbindungen (Ligaturen), die ornamentale Verzierungen,

subtile Tonhöhenveränderungen sowie Zeichen für emphatisches Beben auf

einer Tonhöhe fordern und ihre Umsetzung ist eine Herausforderung für

heutige Musiker.

Die Auswahl der auf dieser CD aufgenommenen

Lieder aus dem Codex 9 der Abtei Dendermonde zeigt einen repräsentativen

Querschnitt vom Liedschaffen Hildegard von Bingens.

Zu den Melodien

Im

Gegensatz zu den traditionellen Gregorianischen Chorälen wählt

Hildegard von Bingen für den Beginn ihrer Lieder oft eine Tonformel, die

nonverbal mit dem emphatischen Ausruf „O“ den Modus des Liedes

vorstellt und damit die Konzentration und Kontemplation des Sängers

einleitet. Diese Tonformeln spinnen sich mit einer Variationsfreude fort

und umkreisen dabei das Wesentliche — den textlichen Inhalt.

Im

Gegensatz zu den traditionellen Gregorianischen Chorälen wählt

Hildegard von Bingen für den Beginn ihrer Lieder oft eine Tonformel, die

nonverbal mit dem emphatischen Ausruf „O“ den Modus des Liedes

vorstellt und damit die Konzentration und Kontemplation des Sängers

einleitet. Diese Tonformeln spinnen sich mit einer Variationsfreude fort

und umkreisen dabei das Wesentliche — den textlichen Inhalt.

Besonders

auffällig ist auch die Verwendung von Kirchenton arten in authentischer

(melodisch in die Höhe strebender) und plagaler (den Grundton

umspielender) Form in ein und demselben Gesang. Innerhalb der Tradition

wurde die Ausführung in nur einer Kirchentonart gefordert, aber auch

darüber setzt sich die eigenwillige „Sybille vom Rhein“ hinweg. Die so

erreichte Ausweitung des Tonraumes und die repetitiven Wiederholungen

einzelner Melodieteile und musikalischer ‚patterns’ lassen eine weitere

Eigenart Hildegards deutlich zu Tage treten.

In der vorliegenden

Einspielung werden einigen der Antiphone für das Stundengebet auch die

entsprechenden Psalmen hinzugefügt, um die ursprüngliche liturgische

Verwendung zu verdeutlichen. Die häufig in der Handschrift hinzugefügten

Psalmtonformeln am Ende der Antiphonen auf die Vokale e-u-o-u-a-e — das sind die letzten Vokale der so genannten kleinen Doxologie Gloria Patri et Filio (...) seculorum. Amen,

die zum Abschluss des Psalmtextes gesungen werden — geben dabei

Aufschluss über die Schlussformel des Psalmtons sowie über die

Eingangsformel und den Rezitationston.

Cantus et melodia

Hildegard

selbst bezeichnet ihre Lieder als „cantus et melodia“, was heißt, dass

die Texte auch ohne Melodie für sich stehen könnten. Die Intensität der

Lieder entfaltet sich musikalisch über die subtile Modulation der

Tonarten und den Reichtum der Melodievariationen innerhalb eines Liedes.

Um einen neuen Aspekt im Text darzustellen mischt sie und wechselt sie

die Kirchentonarten, sodass sich die Klanglichkeit in Kürze völlig

verändern kann. Durch die Verwendung eines b-Vorzeichens wird zum

Beispiel aus einem dorischen Modus ein phrygischer. Durch die Verlegung

des Halbtonschrittes ändert sich die Klangwelt und korreliert mit der

Struktur des Textes.

Diese geschickte Wort-Klang-Verbindung

erhöht die suggestive Kraft der Texte. Hildegard nimmt sich also

Freiheiten gegenüber den geforderten Vorgaben zu den Kirchentonarten.

Sehr streng eingehalten werden diese zur gleichen Zeit beispielsweise

bei den Zisterziensern unter Bernhard von Clairvaux, der fordert, dass

jeder Gesang im Rahmen von einer der acht Kirchentonarten bleiben muss.

Auch

im Hinblick auf den Tonumfang geht Hildegard eigene Wege. Viele ihrer

Gesänge bewegen sich innerhalb von fast zwei Oktaven und einige ihrer

Kompositionen haben gar einen Ambitus (Tonhöhenumfang), der zwei Oktaven

übersteigt, wie das Beispiel der Antiphon an die Apostel O lucidissima apostolorum turba auf der eingespielten CD eindrucksvoll belegt.

Diese

musikalische Freiheit muss exzentrisch gewirkt haben, denn

normalerweise soll nach den Musiktraktaten der Hildegard-Zeit ein

liturgischer Gesang sich höchstens über eine Oktave und einen

zusätzlichen Ton über oder unter der Skala ausdehnen. Das lässt

allerdings auch vermuten, dass sich in Hildegards klösterlichem Umfeld

virtuose Sängerinnen befanden, die in der Lage waren, solche stimmlichen

Anforderungen zu meistern.

Die Gesänge sind oft nicht

zweifelsfrei einem liturgischen Zeitpunkt zuzuordnen. Es handelt sich

hier nicht um einen in sich geschlossenen Codex wie ein Antiphonar oder

ein Graduale für den Ablauf des Kirchenjahres, sondern vielmehr um

textliche und musikalische Ergänzungen zu den Stundengebeten und

Messfeiern im Kloster auf dem Rupertsberg.

Die Texte

Der

stark bildhafte und teilweise drastische Charakter, der die visionären

Schriften Hildegards auszeichnet, findet sich auch in den Texten ihrer

Lieder. Die Einheit der Kirche steht dabei im Mittelpunkt. Der Teufel in

verschiedenen Gestalten will diese Einheit mit allen Mitteln zerstören

und lockt Einzelne weg aus der Gemeinschaft. Die Gläubigen sollen

aufgerüttelt werden.

Die Hierarchie des Himmels — bestehend aus

Gottvater, der Gottesmutter Maria, dem Heiligen Geist, den Propheten und

Patriarchen, den Aposteln, den Märtyrern und den Heiligen – wird

hymnisch angerufen, den Menschen bei ihrem Kampf gegen das Böse helfend

und unterstützend zur Seite zu stehen. Dabei wird in der Antiphon O splendidissima gemma

Maria als „strahlendste Gemme“ und „funkelnder Edelstein“ gepriesen,

welche die Schlange des Paradieses überwindet und die Erbsünde tilgt.

Die „prima materia“ in dieser Antiphon ist ein Begriff, der ursprünglich

aus Aristoteles Werk Metaphysica

entstammt. „Materie ohne Form“ nannte er sie, oder

„erste Materie“, die selbst ohne Form war und selbst nichts

darstellen kann.

Theologisch

meint Hildegard wohl den Zustand der erschaffenen Welt aus dem Nichts —

noch vor dem Sündenfall. Die Schuld, die Eva dann auf sich (und damit

auf die ganze Welt) geladen hat, soll getilgt werden und dazu benutzt

Gott das Wort (verbum). Er dreht den Namen „Eva“ um und macht daraus das

„Ave“, mit dem der Engel Gabriel Maria grüßt und ihr verkündet, dass

sie den Sohn Gottes gebären wird. Allein durch das Wort und die

Zustimmung Marias wird das Kommen des Heil bringenden Erlösers

ermöglicht. Und so wird aus der formlosen Materie bei Hildegard die

„lucida materia“ – die leuchtende Materie, die alle Tugenden in sich

trägt.

Auch die Patriarchen und Propheten spielen für die Heilserwartung eine zentrale Rolle, wie es in der Antiphon O spectabiles viri

anklingt. Sie haben „das Geheime (Dunkle) durchschritten“

(pertransistis occulta) und sehen mit ihren geistigen Augen ein neues

Licht. Sie sind wie „kreisende Räder“, die unaufhörlich das Kommen des

Erlösers voraussagen und so für die Erlösung der Seelen sorgen. Die

Metaphern von Rädern und Licht finden wir häufig in den Texten als

Zeichen des Weges und des Ziels der Gläubigen.

Die Märtyrer werden in der Antiphon Vos flores rosarum

als Werkzeuge des Himmels und ihr vergossenes Blut durch das Bild einer

„blühenden Rose“ beschrieben und die Heiligen wie Disibod sind „Säulen,

die niemals wanken“. Der Heilige Geist ist die Kraft der Liebe, der mit

Feuer das Böse zu verbrennen vermag und es mit dem Schwert durchbohrt.

Der „Kuss des Friedens“ (der „osculum pacis“ aus der Antiphon Caritas habundat)

ist dabei Zeichen der Dreieinigkeit, Ritual der Gläubigen untereinander

und zugleich „Klang und Leben“. Er gibt der vorliegenden CD ihren

Titel.

Hildegard of

Bingen one of the most individual personalities of the 12th century is

hidden behind this famous and sonorous name. The tenth child of noble

parents Hildebert and Mechthild, she was handed over to the

Disibodenberg Benedictine Monastery as an oblata (gift to God for

a spiritual life) at the age of eight. She received her religious

training and a comprehensive education there from the nun Jutta of

Sponheim, who was eight years her senior.

On 1 November 1112 she

was locked in a tower in Disibodenberg Monastery, inhabited by

Benedictine monks since 1108, together with her teacher in accordance

with latter’s will. After years of the ascetic life, accompanied by

visionary images, the retreat became a convent for women and Hildegard

became the magistra of the female pupils gathered together there.

With enormous self-assertion and in the face of great resistance, she

founded and directed the Rupertsberg Convent near Bingen on the Rhine.

Young noblewomen were primarily taken in there who contributed a not

inconsiderable dowry to the convent, causing disapproval amongst the

clergy and the populace. Soon rumours circulated about the nuns, who

ostensibly celebrated the liturgy in the convent in their very own way —

like real noble brides, with loose hair and jewellery.

Despite

all animosities, Hildegard became an admonisher and comforter of her

time. During her lifetime, she corresponded with kings, princes,

bishops, abbots and abbesses in whose convents strife and discord

reigned. An exchange of letters with the very influential Cistercian

monk Bernard of Clairvaux has also been preserved; he is the one who

defended Hildegard’s statements and visions to Pope Eugene III at the

Synod of Trier in 1147/48 and encouraged Hildegard to write them down.

At that time, visions and visionary literature were often suspected of

disseminating unauthorised heretical thinking that could harm the

Church, but the blessing of this Pope contributed even more to

Hildegard’s popularity. Following more extended journeys delivering

sermons and making visitations, Hildegard finally returned to her mother

convent in 1171 where she died at the age of 81 on 17 September 1179.

The

posthumous canonisation of Hildegard, expected by many people, did not

take place, nor did it occur during the ensuing centuries. Upon the

initiative of Pope Benedict XVI, however, she was added to the canon of

the universal Church on 10 May 2012 and can therefore be venerated in

the entire worldwide Church as a saint even without formal canonisation.

Posterity permanently acknowledges the work of Hildegard, as documented by a quotation from the Schedelsche Weltchronik

of 1493: She “had the grace, out of divine power (although a layperson

and unlearned), to frequently experience visions in her sleep, and to

learn not only to speak Latin but also to write and create poetry, as

well as many books containing Christian teachings.”

In her first and most famous work Scivias

(Know the Way), the meanwhile 42-year-old displays and interprets the

history of world salvation in 26 visionary pictures — from the Creation

to the end of time. In it, Hildegard depicts a mystical path of the soul

(anima) towards salvation through inward meditations and

suffering. Hildegard’s central themes are the unity of the Church with

the help of the prophets, apostles and saints, and the struggle against

evil, appearing in the personal or disguised form of the devil. Each

individual soul is thus constantly in danger of being wrested from the

flock of believers.

The Manuscript

The

Dendermonde Codex was written during Hildegard’s lifetime, around 1175,

and was a gift of Hildegard to the Cistercian convent of

Villers-la-Ville — today in Belgium — a subsidiary of Clairvaux founded

by St Bernhard and Godfrey III, Duke of Brabant. It contains Hildegard’s

famous collection Symphonia harmoniae caelestium relevationum with 56 songs, intended to be sung at the Liturgy of the Hours and the Mass.

Sabine

Lutzenberger and Baptiste Romain perform these from reproductions of

the original manuscript, thus arriving at a deeply moving and subtle

interpretation all their own which respects many idiosyncrasies of the

notation.

The Songs

These songs are notated by

means of a complex system of graphic note symbols (neumes) in an early

form of German horseshoe-nail notation in a 5-lined system. The C and

F-clefs provide definite indications of pitches, with the C-line

coloured yellow and the F-line red for better legibility. In this way,

the half-steps C-B and F-E are clarified and made graphically visible.

The many different neume symbols also contain, alongside individual

notes, connections between notes (ligatures) which call for decorative

ornaments, subtle pitch changes as well as emphatic trembling on a

single pitch, and their realisation remains a challenge for musicians

today. The selection of songs recorded on this CD from Codex 9 of

Dendermonde Abbey shows a representative cross-section of Hildegard of

Bingen’s song composition.

About the Melodies

In

contrast to the traditional Gregorian chants, Hildegard of Bingen often

chooses a tone formula for the beginning of her songs which introduces

the mode of the song with the emphatic outcry “O”, thus initiating the

concentration and contemplation of the singer. When these tone formulas

unfold, they delight in variation whilst encircling the essential matter

— the textual content. The use of church modes in authentic

(melodically striving upwards) and plagal (circling round the tonic)

form in one and the same song is also particularly striking. An

execution in only one church mode is called for within the tradition,

but the strong-willed “Sybille of the Rhine” goes beyond this as well.

The expansion of the tonal space and repetitions of individual melodic

parts and musical patterns clearly reveal yet another of Hildegard’s

special idiosyncrasies.

On the present recording, the

corresponding psalms are also added to several of the antiphons for the

Liturgy of Hours in order to clarify the original liturgical

application. The psalm-tone formulas frequently added at the end of the

antiphons on the vowels e-u-o-u-a-e in the manuscript — these are the

last vowels of the so-called Little Doxology (Gloria Patri et Filio (...) seculorum. Amen)

sung at the conclusion of the psalm text — provide information about

the closing phrases of the psalm tone and about the introductory

formulas and recitation tone.

Cantus et melodia

Hildegard herself designated her songs as cantus et melodia,

meaning that the texts can also stand by themselves without melody. The

intensity of the songs develops musically by means of the subtle

modulation of keys and the richness of the melodic variations within a

single song. To represent a new aspect in the text, she mixes and alters

church modes, so that the sonority can completely change within a short

time. By using a flat accidental, for example, the Dorian mode is

transformed into the Phrygian. Relocating the half-step alters the

sound-world and correlates with the structure of the text. This skilled

connection of word and sound increases the suggestive power of the

texts.

Hildegard thus takes liberties regarding the specified

requirements concerning the church modes. During the same period, these

are maintained very strictly by the Cistercians under Bernard of

Clairvaux, for example, who requires that each song must remain within

the limits of one of the eight church modes.

Hildegard also goes

her own way as regards range. Many of her songs extend over almost two

octaves and several of her compositions even have an ambitus (pitch range) exceeding two octaves, as the example of the antiphon to the apostles O lucidissima apostolorum turba on the present CD impressively shows.

This

musical freedom must have made an eccentric effect; according to the

musical treatises of Hildegard’s time, a liturgical song should normally

only extend, at most, over an octave and an additional tone above or

below the scale. This also leads us to surmise, however, that there were

virtuoso singers in Hildegard’s cloistral surroundings who were able to

master such vocal requirements.

Often, the songs cannot be

clearly allocated to a liturgical point in time. This is not a

self-contained codex such as an Antiphonary or a Gradual for the course

of the church year; far more, these are textual and musical supplements

to the Liturgy of the Hours and the Mass at Rupertsberg monastery.

The Texts

The

strong images and at times drastic character that mark the visionary

writings of Hildegard are also found in the texts of her songs. The

unity of the Church is at the centre of their focus. The devil in

various forms wants to destroy this unity with all means, luring

individuals away from the community. The believers should be made to be

watchful.

The hierarchy of Heaven — consisting of God the Father,

Mary the Mother of God, the Holy Spirit, the prophets and patriarchs,

the apostles, the martyrs and the saints — is called upon, through

hymns, to stand by, assist and support the people in their struggle

against evil. Thus Mary is praised in the antiphon O splendidissima gemma

as “the most brilliant gem” and “sparkling precious

stone” who overcomes the snake of Paradise and redeems original

sin. The prima materia

in this antiphon is a term originating in Aristotle’s Metaphysica. He

calls it “material without form”, or “first material” which was itself

without form and cannot itself represent anything.

Theologically,

Hildegard is most likely referring to the condition of the created

world out of nothing — before the Fall. The guilt that Eve then incurred

upon herself (and thus upon the whole world) is to be redeemed; God

uses the Word (verbum) for this. He turns the name “Eva” round to

make “Ave” with which the Angel Gabriel greets Mary, proclaiming to her

that she will bear the Son of God. The coming of the salutary redeemer

is made possible through the Word and the assent of Mary alone. And this

is how the formless material becomes the lucida materia for Hildegard — the luminous material that contains all virtues within itself.

The patriarchs and prophets also play a central role for the hope for salvation, as is sounded in the antiphon O spectabiles viri. They have “overcome the occult (darkness)”, pertransistis occulta,

and see a new light with their spiritual eye. They are like “circling

wheels” that perpetually predict the coming of the Redeemer and thus

ensure the redemption of souls. The metaphors of wheels and light are

frequently found in the texts as symbols of the path and goal of the

believers. The martyrs are described in the antiphon Vos flores rosarum

as a tool of Heaven and their bloodshed through the image of a

“blossoming rose”; saints like Disibod are “pillars that never falter”.

The Holy Spirit is the power of lover that can burn evil with fire and

pierce it with the sword. The “kiss of peace” (osculum pacis from the antiphon Caritas habundat)

is the symbol of the Holy Trinity, the ritual of the believers amongst

each other and, at the same time, the “sound of life”. It gives the

present CD its title.