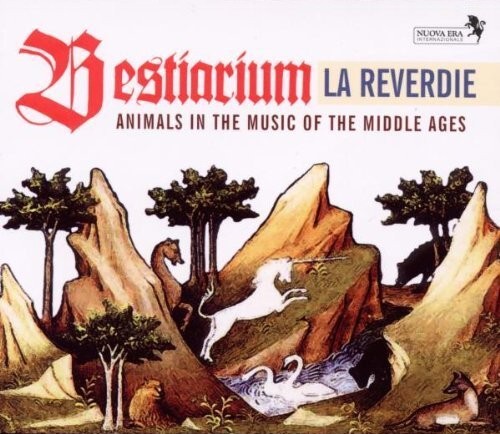

Bestiarium / La Reverdie

Animals in the Music of the Middle

Ages

medieval.org

Nuova Era 6970

1991

1. Chançonette

~ A la cheminée ~ VERITATEM [2:02] anonimo francese, mottetto

2. Jean VAILLANT. Par mantes foys [2:17] virelai

3. Oswald VON WOLKENSTEIN. Ihr alten weib frewet ew [3:12]

4. Jacopo da BOLOGNA. Aquila altera ~ Creatura gentile ~ Uccel di

Dio [2:11] madrigale

5. Aquila altera [2:24] dal Codice di Faenza

6. Canto delle scolte [3:05] anonimo modenese

7. En ma forest [3:53] anomimo francese, pastourelle

8. MARCABRU. L'autrier jost'una sebissa [2:36] pastourelle

9. CB 185. Ich was ein chint so wolgetan [2:45] dai Carmina Burana

10. Donato da FIRENZE. Lucida pecorella [4:15] madrigale

11. Na coire ar na sleibhtibh [2:43] tradizionale irlandese, double jig

12. Fuweles in the frith [2:23] anomimo inglese

13. Jacopo da BOLOGNA. Oseletto selvaggio [3:46] madrigale

14. Bryd one breere [3:07] anonimo inglese

15. Donato da FIRENZE. L'aspido sordo [2:29] madrigale

16. Ar bleizi-mor Les Loups-de-Mer [2:11] tradizionale bretone

17. Donato da FIRENZE. I' fu' già bianch'uccel [3:18] madrigale

18. Giovanni da FIRENZE. Con bracchi assai [3:11] caccia

19. Oswald von WOLKENSTEIN. Wolauff gesell wer jagen well [2:14]

20. Francesco LANDINI. Chosì pensoso [2:27] caccia

LA REVERDIE

Elisabeta de' Mircovich, voce, ribeca, santur

Claudia Caffagni, voce, liuto, tabor

Ella de' Mircovich, voce, arpa, lira

Livia Caffagni, voce, flauti, viella

English liner notes

Production: Alessandro Nava & Danilo Prefumo

Artistic Supervision: Danilo Prefumo

Artistic Director: Doron David Sherwin

Sound Engineer: Roberto Chinellato

Recording Location:

Salone del Parlamento del Castello di Udine,

May 6/9, 1990

© Ella de' Mircovich

English Translation: Timothy Alan Shaw

Italian Translation: Ella de' Mircovich

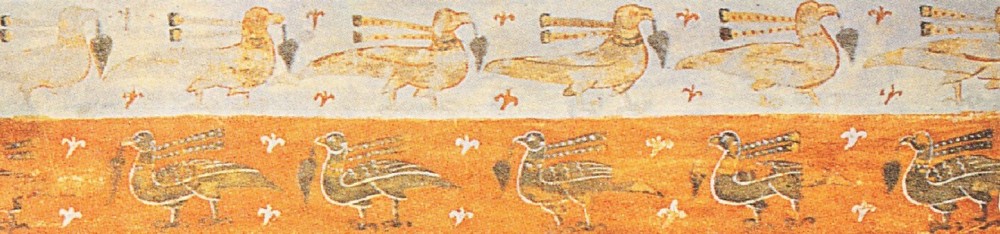

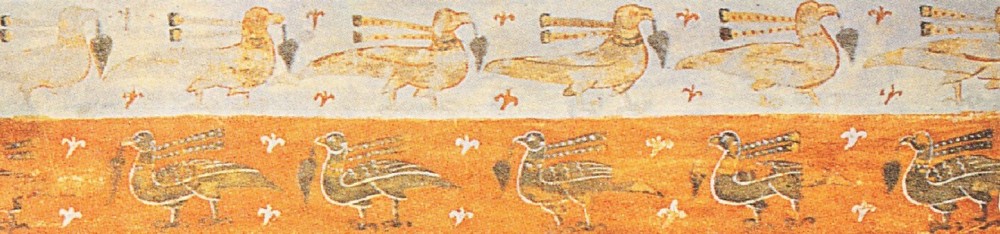

Cover Photo:

Echternach Codex Aureus Epternacensis,

Nürnberg, Germanisches National Museum

Photo: Paolo Da Col

Cover Design: Giuseppe Spada

Art Direction: Xerios

1991 - Printed & Manufactured in Italy

Ⓟ 3 - 1991 NUOVA ERA RECORDS

Si ringraziano:

il Direttore dei Musei, l'Assessore Prof. Barbina, il Dott. Malcangi

Our thanks to:

the Director of the Museums, Prof. Barbina, Dr. Malcangi

|

FONTI PER "BESTIARIUM" - SOURCES FOR THE "BESTIARIUM":

MS Ed. IV 6; Bamberg, Stiftsbibl.

MS 1047; Chantilly, Musée Condé

Wolkensteinhandschrift B; Innsbruck, Universitätsbibl.

MS Panciatichi 26; Firenze, Bibl. Naz.

Cod. Capit. 0.1.4; Modena, Bibl. Estense

F. O'Neill: The Dance Music Of Ireland

MS Douce 139; Oxford, Bodleian Lib.

MS Palatino 87 "Squarcialupi"; Firenze, Bibl. Laurenziana

Muniment Roll 2W.32; Cambridge, King's College

MS Add. 29989; London, British Museum

STRUMENTARIO - INSTRUMENTS:

LIUTO/LUTE - I. Magherini; Roma, 1988

ARPA/HARP - P. Zerbinatti; San Marco di Mereto di Tomba, 1988

LIRA/LYRE - P. Zerbinatti; San Marco di Mereto di Tomba, 1987

VIELLA/VIELLA - S. Fadel; Valmadrera, 1989

RIBECA/REBEC - B.Tondo e P. Zebinatti; Udine, 1987

SANTUR/SANTUR - E. Laurenti; Bologna, 1988

TABOR/TABOR - P. Williamson; Lincoln, 1979

FLAUTI/FLUTES - A Zaniol; Venezia, 1982 (A)

F. Delessert; Fribourg, 1983 (S)

C. Collier; Berkeley, 1984 (T)

|

BESTIARIUM

Animals in the Music

of the Middle Ages

ELLA DE' MIRCOVICH

"Into the wode the soun gan schille

that alle the wilde beestes that thee beth

for joy abouten him thai teth"

"La civiltà materiale non aveva ancora separato dal cosmo l'uomo

del Medioevo, ch'era un animale ancora semiselvatico, per il quale il

tempo cambiava ritmo e sapore a seconda delle stagioni. Gli

intellettuali non vivevano rinchiusi in una stanza, ma più

spesso negli orti e nei prati, e tutti i chiostri si aprivano su un

giardino pieno di fiori e d'uccelli (...) Nel bosco i cavalieri a volte

incontravano dei draghi, ma più spesso inseguivano daini e

cerbiatte" (L'arte e la società medievale, 1977).

Così abilmente condensato in poche righe dal grande Georges

Duby, ecco lo scenario naturale che fa da onnipresente sfondo a tutte

le manifestazioni espressive del Medioevo: una costante discreta,

elusiva ma imprescindibile, una sorta di sommesso ma fondamentale

bordone che è giocoforza immaginarsi accompagnamento ad ogni

forma d'arte di quell'epoca. Il mondo vegetale, e soprattutto quello

animale, ancora più movimentato e vario, ne è una

componente fondamentale, ed è ovvio che abbia costituito un

serbatoio inesauribile di stimoli, ispirazioni, riflessioni, immagini e

risorse al quale si attingeva da ogni parte: un serbatoio che ha

fornito prezioso materiale ad immaginari collettivi e scuole poetiche,

a Trivium e Quadrivium, a teologi e maestri comacini.

Il Medioevo

pullula d' animali: e non esclusivamente nelle sue immense foreste, che

solo in parte la comunità umana comincia ad intaccare nel suo

impeto dissodatore. Dall'araldica alla gastronomia, dalla teologia alle

decorazioni miniate gli animali, ben più numerosi dei loro

signori e padroni umani, invadono tutta l'Europa, tanto negli ambienti

profani che in quelli sacri. Al tempo della riforma cistercense questa

invasione esornativa aveva evidentemente raggiunto, nelle case di Dio,

livelli di guardia; perlomeno a detta di Ailredo di Rievaulx, che nel

suo "Speculum Charitatis" tuona: "perchè, nei chiostri dei

monaci, queste gru e queste lepri, questi daini e questi cervi, queste

gazze e questi corvi? Non sono gli strumenti degli Antoni e dei Macari,

ma piuttosto trastulli di donne". L'invettiva di Allredo rifornisce

un'ottima - ancorchè forzatamente semplicistica - chiave di

lettura della posizione dell'animale nelle arti medievali. In effetti,

la posizione in esse dell'animale oscillerà costantemente fra i

due significativi poli stabiliti da Ailredo: "strumenti" dei Padri

eremiti del deserto (tanto dell'arido deserto meridionale di Antonio e

Macario quanto del deserto marittimo e insulare di Brendano, Patrizio e

Colombano) e, per estensione, strumenti didascalici e simbolici

dell'allegoria religiosa e morale; e "trastulli" per le donne ed in

generale per tutti quegli "ordines" della società esonerati dal

praticare l'austera autodisciplina monastica.

Questa

"strumentalizzazione" dell'animale a fini simbolici ed istruttivi non

era di per sé una pratica nuova. Possiamo rintracciarne la

matrice in un'opera alessandrina del Secondo Secolo, tradotta in latino

nel Quinto: il "Physiologus", ricopiato, rielaborato, ampliato ed

imitato in tutta Europa - dalla magnifica versione anglosassone del

Decimo secolo sino alle relazioni di viaggio esotiche, da Marco Polo a

Sir John Mandeville, di moda nel tardo Medioevo - dalle cui pagine

fuggirono, come da uno zoo fatato, unicorni e basilischi, fenici e

draghi, tutta la variopinta fauna dei "Bestiaria". In questi ultimi,

come rileva giustamente Jacques Le Goff, "la sensibilità

zoologica si alimentò d'ignoranza scientifica; l'immaginazione e

l'arte, questo è vero, guadagneranno quel che la scienza

perderà" (La Civilisation de l'Occident Médiéval,

1964).

E tuttavia è anche da questa tradizione di una zoologia

favolosa e moraleggiante che prenderà avvio - in un certo senso

rivolta verso il polo del "trastullo" - quella trattatistica venatoria

nella quale per la prima volta nel Medioevo faranno capolino le scienze

naturali propriamente dette, e delle quali i primi cultori non saranno

dei chierici (intenti a spiegare le allegorie mistiche celate nella

singolare tecnica riproduttiva dei leoni), bensì aristocratici

cacciatori dalla dubbia reputazione morale, come Federico II di Svevia,

("De Arte Venandi Cum Avibus"), Gaston Phébus ("La Venerie") e

Edward Plantagenet, duca di York ("The Master Of Game"). Quanta

all'animale "trastullo", il suo habitat coincide, beninteso, con la

novellistica d'intrattenimento e con la poesia profana. Non dobbiamo

tuttavia commettere l'errore di vedere questi due generi in rapporto

antagonistico con quelli citati più sopra: molto spesso la

letteratura "d'evasione" mutua, sia pure con stile più

disinvolto ed immediato, i temi delle opere di estrazione più

squisitamente moraleggiante, degli "exempla" da omelia.

Quanto abbiamo rilevato in merito alla polivalenza funzionale

dell'animale nell'arte medievale vale, naturalmente, anche per la

musica, e l'eterogeneità dei brani che abbiamo selezionato per

questo florilegio mira appunto a dare un'idea dell'enorme

varietà d'ispirazione che quadrupedi, uccelli e pesci offrirono

alla creatività dell'epoca. Il primo gruppo di brani consacrato

agli animali "positivi", positivi per la loro valenza simbolica, per il

ruolo sostenuto nell'economia del testo, o perchè delineati alla

stregua di complici e rappresentanti delle forze positive,

rigeneratrici, dell'Universo. A questa prima sezione fra da contraltare

la terza, pullulante dei corrispettivi animali "negativi", oscuri,

inquietanti; le rimanenti due sezioni, infine, gettano uno sguardo su

due modalità d'interazione fra animale e uomo che hanno

conferito un'impronta caratteristica al Medioevo, assurgendo spesso -

al di là della loro rilevanza strettamente economica - alla

dignità di metafore spirituali gravide di significati e di

ammaestramenti: pastorizia e caccia.

BESTIARIUM

Animals in the Music of the Middle Ages

ELLA DE' MIRCOVICH

"Into the wode the soun gan schille

that alle the wilde beestes that ther beth

for joy abouten him thai teth"

"Material

civilisation had not yet separated man from the cosmos; man was still a

half-savage animal for whom time changed rhythm and flavour with the

seasons. Intellectuals did not live shut away in a room but more often

in kitchen gardens and in the fields, and all the cloisters opened out

onto gardens full of flowers and birds [...] Knights sometimes met

dragons in the forest, although more often they would follow fawn and

deer" (Medieval art and society, 1977). Here, so skilfully concentrated

into a few lines by the great Georges Duby, is the natural landscape

that is an ever-present backdrop to all the expressions of the Middle

Ages: a discreet, elusive but inescapable constant, a sort of soft but

fundamental bourdon that must be imagined as the accompaniment to every

form of art of that period. The vegetable, and especially the animal

world, still lively and varied, is a fundamental element, and obviously

represented an inexhaustible stock of stimuli, inspirations,

reflections, images and resources to be drawn upon by one and all: a

stock that offered precious material to the collective imagination and

to poetic schools, to the liberal arts, to theologians and to the

Romanesque stone masons of Como.

The Middle Ages were alive with

animals, and not only in the immense forests that had only partially

been whittled away by the ploughshares of the human community. From

heraldry to gastronomy, from theology to miniature decoration, animals

invade all of Europe, far more numerous than their human lords and

masters, in both secular and sacred contexts.

By the time of the

Cistercian reform this decorative invasion must have reached danger

levels, at least in the case of God, for Ailredo de Rievaulx thunders

forth in his "Speculum Charitatis": "why in monks's cloisters are there

these cranes and these hares, these fawn and deer, these magpies and

crows? They are not the instruments of Anthony and Macarius but are

rather women's playthings". Ailredo's invective provides us with an

excellent - albeit necessarily simplistic - key for the interpretation

of the position of animals in the arts of the Middle Ages. In these arts

their position oscillates between two significant poles fixed by

Ailredo: "instruments" of the hermits of the desert (both the arid

middle-eastern desert of Anthony and Macarius and the maritime, island

desert of Brendan, Patrick and Columbus) and, by extension, didactic,

symbolic instruments of religious and moral allegory; and "playthings"

for women and more generally for all those "orders" of society that were

not obliged to follow the austere self-discipline of the monks.

This

"instrumentalisation" of the animal for symbolic and instructional

purposes was not in itself a new practice. We can find its model in an

Alexandrine work of the second century, translated into Latin in the

fifth: the "Physiologus", then recopied, revised and imitated all over

Europe - from the magnificent Anglo-Saxon version of the tenth century

to accounts of exotic travels, from Marco Polo to Sir John Mandeville,

that were the fashion in the late Middle Ages -, from the pages of which

unicorns and basilisks, phoenixes and dragons leap forth, as in an

enchanted zoo, with all the many-coloured fauna of the "Bestiaria". In

these works, as Jacques Le Goff rightly notes, "zoological sensibility

was fed upon scientific ignorance; imagination is art, this is true,

they will win more than science loses" (La Civilisation de l'Occident

Médiéval, 1964).

And yet it is from this tradition of fabulous and

moralising zoology too that the various treatises on hunting will arise -

directed in a sense towards the pole of the plaything - and where for

the first time in the Middle Ages natural sciences in the true meaning

of the expression will appear. The authors of these works will not be

men of the church (intent on explaining the allegorical mysteries hidden

in the singular reproductive technique of lions) but aristocratic

hunters of questionable morality, like Frederic II of Sweden ("De Arte

Venandi Cum Avibus"), Gaston Phébus ("La Venerie") and Edward

Plantagenet, Duke of York ("The Master of Game"). The habitat of the

animal as "plaything" coincides, of course, with the light short story

and profane poetry. We should not, however, fall into the error of

seeing these two genres as being in opposition to with the types of

writings mentioned above: very often "escapist" literature, using indeed

a less serious and more immediate style, borrows the themes of works of

more moralising nature, from the "exempla" to the sermon.

The

observations we have made about the plurality of function of the animal

in Medieval art is of course true of music too, and the heterogeneous

make-up of the pieces we have chosen for this anthology seeks to give an

idea of the immense variety of inspiration offered by quadrupeds, birds

and fish to the creativity of the epoch. The first set of pieces is

devoted to "positive" animals, positive in their symbolic value, in the

role they perform in the text, or because they are portrayed as being

accomplices and representatives of the positive, regenerative forces of

the Universe. This first section finds a contrast in the third set which

teems with corresponding "negative", dark and disturbing animals. The

two remaining sections then cast a glance at two modes of interaction

between animals and man which have left a characteristic mark on the

Middle Ages, and which often attain - quite apart from their purely

textual relevance - the dignity of spiritual metaphors that are dense

with meaning and teachings: the breeding of animals and the hunt.

Nuova Era NUO 6970: