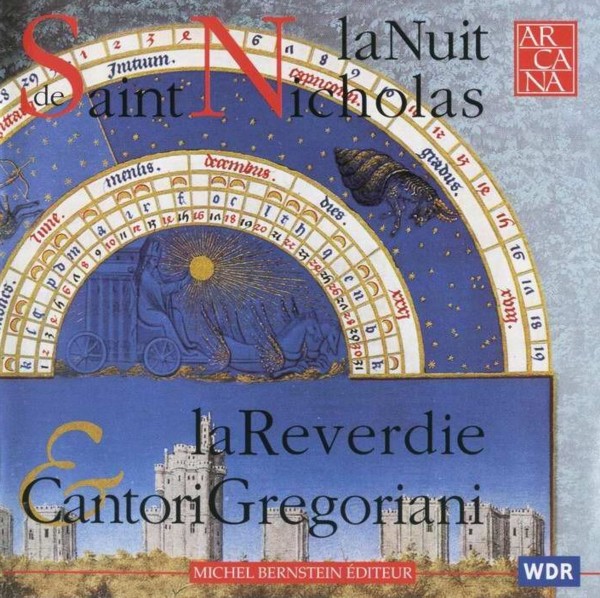

This is a liturgical drama devoted to the Feast of St. Nicholas. Reconstruction by La Reverdie is based on the English antiphonary of the 13th century (Cambridge Univ. Lib. MS Mm 2g).

medieval.org

amazon.com

Arcana 72

abril-mayo de 1998

Modena, S. Damaso, Église de Collegara

Cambridge, University Lib., MS Mm. 2g

Antiphonale Monasticum

01 - Invitatorium. Adoremus Regem

seculorum [7:06]

v 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9

02 - [1:56]

Antiphona. Nobilissimis siquidem

natalibus

v 1 2 3 4

Psalmus I

v 1 2 3 4

03 - [1:39]

Antiphona. Pudore bono repletus

v 1 2 3 4

Psalmus III

v 1 2 3 4

04 - [3:55]

Antiphona. Auro virginum incestus

v 1 2 4, vielle

Psalmus IV

v 1 2 3 4 · cloche 7

05 - Lectio [3:16]

Paul the Deacon, Vita Sancti Nicholai, IXe s.

v 7

06 - Responsorium. Quadam die tempestate

- Mox illis clamantibus [3:41]

v 6 7 8 9

07 - Vox de celo [1:27]

pièce instrumentale (C. Caffagni)

psalterion

08 - Lectio [2:21]

Jacopo of Varagine, Legenda Aurea seu Historia Lombardica, XIIIe s.

v 4, psalterion

09 - Responsorium. Confessor Dei

Nicholaus - Erat enim valde compaciens

[3:55]

v 1 2 3 4

10 - Lectio [5:06]

Paul the Deacon, Vita Sancti Nicholai, IXe s.

v 4 · percussion, tabule 5 1, cloche 1 3

11 - [6:38]

Responsorium. Ex eius tumba - Catervatim

v 6 7 8 9 10

Prosa. Sospitati dedit egros

v 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9

12 - Organum. Ex eius tumba [8:55]

Florence, Bibl. Laurenziana, Ms Plut. 2a

v 1 2 3 4 9

13 - [2:37]

Antiphona. O per omnia laudabilem virum

v 6 7 8 9

Psalmus CL

v 6 7 8 9

14 - Resposorium. Qui cum audissent -

Clara quippe voce [3:26]

v 13 · harpe

15 - [6:18]

Antiphona. Copiose caritatis Nicholæ

v 6 7 8 9

Benedictus

v 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9

16 - [6:45]

Antiphona. O Christi pietas

Magnificat

v 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9

17 - [4:51]

Oracio

Orléans, Bibl, Mun., MS 201

v 1 2 3 4 5 7 8 9 · cloches 10 11 12

ST. GODRIC of FINCHALE. Sainte Nicolas Godes druth

London, British Mus. Lib., MS Royal 5f

v 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9 10 · vielle, cithara teutonica

La Reverdie

1 Claudia Caffagni · voix, cloches, psalterion, tabule

2 Livia Caffagni · voix

3 Elisabetta de' Mircovich, voix, vielle, cloches

4 Ella de' Mircovich, voix, harpe, cithara teutonica

5 Doron David Sherwin, tabule, percussions

direction du répértoire vocal, Roberto Spremulli

I CANTORI GREGORIANI

6 Angelo Corno, voix

7 Giorgio Merli, voix, cloches

8 Alessandro Riganti, voix

9 Roberto Spremulli, voix

10 Fulvio Rampi, voix, cloches

direction, Fulvio Rampi

avec le concours de

11 Yael Manou, cloches

12 Lorenzo Palazzolo, cloches

THE HAGIOLOGY OF FATHER CHRISTMAS

We may, without the slightest doubt, consider Nicholas of Patara as a

beloved and called upon - although changeable- saint. Another of his

prerogatives is his relaxed cosmopolitanism: the appellation which

perhaps best suits him is the offhand and well targeted one used by C.

W. Jones for his book Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari and Manhattan. In

truth, the apparent incongruity of a cohabitation between Asia Minor,

Italy and the United States perfectly sums up the prodigious voyage

made by the patron saint of sailors, pueri cantores, perfumers, pawn

brokers, maidens and spinsters across nations and eras, drawing

Christian and pre-Christian, folk and historical elements to himself -

like all the great miracle workers of the hagiography.

As pertains to history, the facts are, in truth, rather sketchy.

Nicholas is not one of those saints - otherwise sometimes quite well

none and highly venerated- recently expunged from the calendar due to

their bothersome promiscuity with a certain legendary limbo; but he has

avoided by a hair the fate that befell Saint George. What we can be

reasonably certain of is that he was, at the beginning of the 4th

century, a very popular bishop of great integrity in Myra, in Lycia

(today Mugla, a Turkish village) where he died in 314 and where, two

centuries later, his remains were still the object oft veneration. It

is less certain that he was born in Patara and that he was not the same

Nicholas with whom some have tried to identify him, an escapee of

Diocletian's persecution who participated in the Council of Nicaea in

325.

We are on less shaky ground if we set out to look over the steps of his

hagiological curriculum, the first milliary column of which coincides

with a 9th century biography in Greek, as fanciful as it was

appreciated. The following 'boom', took place one hundred years later,

at the imperial court of the Occident, where Theophano, Byzantine wife

of Otto II, actively promoted the recognition and cult of he who was

perhaps the most eminent saint of Eastern Christianity. In 1087, an

offensive by the Saracens served as a pretext for a group of Italian

knights to steal the saint's relics and transfer them from a

no-longer-peaceful Myra to Bari, his birthplace. Over these relics, one

of the most majestic Romanesque cathedrals was built with astonishing

speed. As early as 1195, Pope Urban II organised a Council there in

which participated - another significant coincidence which would be

extremely propitious to the pan-European success of Saint Nicholas-

Anselm of Aosta and Canterbury, an illustrious and influential

intellectual who happened to be eminently cosmopolitan. In fact,

shortly after Anselm returned to his archbishopric in England, Saint

Nicholas, patron saint of sailors, was so popular with that sea-going

people that Godric, a former pirate who had become a holy hermit,

conversed with him (according to his contemporary biographer Reginald

of Durham) during his musical ecstasies in order to learn, word by word

and note by note, the moving little piece included in this collection.

In Fleury, at more or less the same period, four liturgical dramas mere

devoted to a famous manuscript: a record for which no other saint can

compete.

These ludi which present obvious textual and melodic links with the

rich but more strictly liturgical repertoire associated with the saint,

draw largely from the vast collection of fabulous miracles which had

accumulated over the centuries and long journeys. The inventory is as

heterogeneous as possible, and extraordinarily new exploits were added

to nearly every account of the saint's life: from the first drafting by

the Byzantine Patriarch Methodus, translated into Latin by Paolo

Diacono in the 9th century, up to Jacopa da Voragine's Legenda Aurea,

seu Historia lombardica, a sort of hagiographic summa, a 13th century

martirologium vademecum - and the innumerable versions of this, each of

them embroidered with later miracolous triumphs, marked by a

predominant parochialism. Starting in Constantinople, this hagiographic

career of Saint Nicholas attains such proportions that it even reached

Island where we find a Nikolassaga Biskupa. It was on the occasion of

these boreal tours in Germanic climes that the good bishop of Myra was

equipped wilh one of his most characteristic - and enigmatic -

attributes: a broom. In the 15th century, it was so well known, even in

Italy, that it appears in his hand in the splendid painting cycle that

Gentile de Fabriano dedicated to the saint: an intriguing object

difficult to explain, unless ¡t is simply included it amongst the

items of this 'store of collective representations, a sort of attic in

which one accumulates immemorial, vague, nearly forgotten customs and

beliefs, traditions and rituals' about which the American researchers

Sheridan and Ross speak in their study of pre-Christian substrata in

the worship of saints in the Middle Ages.

For the Christian in the Middle Ages, it was inevitable that, in his

devotional practices, he normally address himself not directly to the

hierarchic pinnacle of the pyramid (the Omnipotent), but to one of His

intermediaries or vassals, the comites palatini of Heaven. Moreover,

for almost everyone, terrestrial authority was identified not so much

with the emperor, the king or the pope, as with much closer figures,

such as the local feudal lord or bishop, to whom direct contact with

the Supreme Power was deferred. So it was that Saint Nicholas, bishop,

pastor and patron saint of a small community in the real vicissitudes

of his life, took on, after his death the comforting and semi-divine

function of tutelary god endowed with a vast range of social categories

and activities. The heterogeneity of his competencies as patron saint

unrivalled: there is hardly another saint to whom the protection of

such a large number of towns and countries - stretching from the

Atlantic coasts to orthodox Russia - was entrusted.

And as if that were not enough, even the thaumaturgical attitudes

peculiar to Saint Nicholas have something all-encompassing, an

evocative power so elementary and arch-typical - and thus culturally

ubiquitous - as to make it difficult to decide, on a case by case

basis, whether it is a question of real 'grafts' coming from other

miraculous cycles or rather the manifestation of a universal

storytelling substratum. Our hero's panoply considers all the

miracle-working masterpieces of the hagiology: those which few saints,

as prestigious imitations of the evangelical wonders of Christ himself,

could permit themselves: resurrection of the dead, multiplication of

objects Olympian mastery of the raging elements, a capacity for

interaction with the faithful through a sort of omnipresent and not al

all material 'projection' of his abody - and all that rigorously not

post mortem, the typical condition in which other saints of lesser

calibre, once freed of their carnal burden, begin to give their

measure. Another particularity of Nicholas (other than the marked

sympathy for the weak and defenceless classes - socially, and not only

from a health point of view - such as young girls, children, prisoners

and Jews) is the striking recurrence of the number three, be it of his

debtors or his attributes, a triplicity which we have sought to

underline in musical excursus by that stylised symbolism so dear to the

mediaeval mentality.

If this penchant of Nicholas's for the number three, in its

semi-mythological ritual ingenuity, remind us more of a reminiscence or

a pre-Christian residue rather than a metaphor linked to the Trinity,

also flagrantly pre-Christian is the extravagant contaminatio which

provided Saint Nicholas with the occasion for maintaining his fame up

to our contemporary, so-called 'secularised' world - which, in reality,

in its perceptive

atrophy of the signs of the Sacred, henceforth barely manages to decode

the poorest signs, devoid of the original profundities. be they

Christian or not.

The occasion thanks to which metropolises and media of modern society

are literally invaded every winter by a host of Nicholas fetishes under

the deceitful a appearance of Father Christmas, is, in all probability,

fortuitous. Saint Nicholas was the object of this strange mutilation

precisely because his functional eclecticism made him 'easier to

handle' in such barely conscious operations of anthropological crossed

fertilisation. In his role as patron saint of children and dispenser of

gifts Saint Nicholas was already the favourite of (well-behaved)

Flemish and Dutch kids in the 14th century: he brought them gifts on

the day of his liturgical commemoration which, moreover, he still does,

canonically garbed in episcopal ornaments, in several European

countries like Switzerland, part of northern Italy and a number of

regions in Germany. A few centuries later, Dutch Protestants emigrating

to the New World, took with them this nice custom, borrowed from their

Catholic compatriots. And it was precisely in America, the

melting pot par excellence, that the final, most secular and best known

of the bishop of Myra's miracles was accomplished. The Flemish custom

found itself confronted with the Scandinavian traditions relative to

the sacred period of Yol, the days surrounding the summer solstice,

dating which darkness and cold oblige one to remain at home and devote

oneself to small jobs such as building wooden toys for the little ones.

It is also during this same disturbing yet fascinating period that the

ambiguous sovereign god Odin, in his terrestrial appearance as the old

Passer-by, the Vetgamir of Old Norse tradition, visits the homes of

men, distributing gifts to deserving hosts and meting out severe

punishments to the bad. It is this evocative bearded, hoary character,

wrapped in his cloak (originally grey or blue), who merged, a little

more than a century later, with the prelate in red robe: the bishop's

mitre gave way to the Norse hood, but the ecclesiastical purple won out

over the typical Odin colours. And Father Christmas began his

irresistible consumer ascension.

Referring to the decline of the Middle Ages, Johann Huizinga wrote:

'the saints were such real figures, so alive and familiar, that all the

most direct religious surges were inter-linked... in their worship,

whole treasure of current and ingenuous ideas crystallised, and in the

spirit of the people, they lived like divinities'. One could perhaps

relate these considerations to the autumn of our post-industrial

civilisation: Apparently, we also have

a visceral need for this, henceforth rare, hybrid and often grotesque

icons of the Transcendent for one of which Saint Nicholas, the old

friend of children and wayward navigators, had the indulgence and

generosity to serve as a model.

Ella de'Mircovich

Translated by John Tyler Tuttle

THE OFFICE OF SAINT NICHOLAS

The music presented in this recording makes up the near totality of the

Officium Sancti Nicholai Episcopi & Confessoris and consists of

Matins, divided into three Nocturnes, and Lauds. The Office of Saint

Nicholas was structured according te the Roman cursus and then adapted

to the monastic cursus by Guglielmo di Volpiano (+ 1031). After the

Invitatorium with Psalm XCIV, one can recognise the Roman cursus with

its succession, for each of the three Nocturnes, of three antiphons

with the simple corresponding salmody and as many melismatic

responsorie prolixe, each preceded by a reading.

In the first part of the programme, up lathe responsory Qui cum

audissent, we wanted to maintain the liturgical structure of a complete

nocturn in Roman cursus even if, as concerns each piece, we have drawn

from the whole corpus of Matins. Next come the two Anthems intended for

the evangelical chants of Lauds (Copiose caritatis to the Benedictus)

and from the Vespers (O Christi pietas to the Magnificat).

The primary musical source used is the famous Antiphonale

sarisburiense, a diastematic testimony from the 14th century in square

notation which is accepted as authoritative. The order of the pieces of

this manuscript is fundamentally confirmed by the oldest unnoted

antiphonaria, from German and Italian regions, such as the Bamberg

Antiphonarium or that of Ivrea.

As concerns the composition, we may safely assert that these pieces,

even if they do not be long to the so-called 'original content', draw

handfuls from the treasury of Gregorian formulas. Some melodic

behaviour clearly shows a more recent phase of composition: one finds,

for instance highly developed descending successions, both under

isolated form as well as within a neumatic group composed and even, in

one case,

unique (the response Confessor Dei), one encounters an unusual interval

of a major sixth between two consecutive notes on a same syllable.

Nonetheless, the expressive sum which characterises the ultimate

finality of Gregorian chant emerges in a constant manner in the simple

anthems as in the more complex responses: the monody 'explains' the

text in its most profound meanings.

We must point out the phenomenon of prosulation, rather free in this

case, on the final melisma on the word 'sospes' in what is perhaps the

best known piece of the entire Office: the great responsory Ex ejus

tumba (Prossa: sospitati dedit egros). The fame of the responsory was

later confirmed by its being taken up in an organum of the School of

Notre-Dame which we have included in this anthology devoted to Nicholas.

The three simple antiphons (Nobilissimi siquidem, Pudore bono, Auro

virginum) which, with the corresponding psalmody, are preceded by the

Invitatorium (antiphon Adoremus Regem, and Psalm XCIV), are followed,

as we have said, by three responsorie prolixe, each precededed by a

hagiographic lectio. Indeed, there are accounts stating that these

readings were long so appreciated that they took the place of all the

Office's lessons, at the expense of even the reading of the the

Scriptures.

Due to their liturgical destination in the evangelical hymns with

semi-ornamented psalmody (Benedictus and Magnificat), the two antiphons

Copiose caritatis and O Christi pietas, stand out due to their richer

compositional style and larger proportions as compared to the simple

antiphons which precede them. Let us also underline that, in the

antiphon to the Magnificat, O Christi pietas, scholars have identified

the prototype of famous Gregorian chants such as the antiphon O quam

suavis, and the well-known Sanctus VIII of the Missa de Angelis.

Fulvio Rampi

Translated by John Tyler Tuttle

Aknowledgements

La Reverdie played and sang with thoughts turned towards two Klauses:

one, in Paradise, who protects pueri cantores and young maidens; the

other, close to us in friendship and music who continues to work

miracles of generosity, kindness and availability. Our thanks,

therefore, to Klaus Neumann who, with his precious and irreplaceable

presence, guided the seven recording sessions for this disc.