Songs of the Sephardim / La Rondinella

Traditional Music of the Spanish Jews

medieval.org

amazon.com

Dorian Discovery DIS-80105

03·09.1990 - 06.1992

Bradley Hill Presbyterian Church, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

01 - Los gayos empesan a cantar [2:20]

02 - Una hija tiene el rey [3:26]

03 - La prima vez [4:07]

04 - Puncha, puncha [1:49]

05 - A'har noghenim [1:48]

06 - Era escuro [2:19]

07 - Seu shearim [1:36]

08 - Esta montana d'enfrente [3:20]

09 - Una pastora [2:11]

10 - Morena me llaman [1:25]

11 - Nani, nani [1:41]

12 - A la una yo naci [2:22]

13 - Scalerica de oro [3:16]

14 - Yo m'enamori [3:20]

15 - Dos amantes tengo la mi mama [2:26]

16 - Una matica de ruda [2:43]

17 - Los bilbilicos [3:23]

18 - Ir me quero [3:31]

19 - Hija mia [2:52]

20 - Durme, durme, hermozo hijico [2:29]

21 - Avre tu puerta cerrada [1:40]

22 - Noches, noches [1:46]

23 - Partos trocados [2:25]

24 - En la mar hay una torre [1:42]

25 - Esta Rachel la estimoza [1:11]

26 - Cuando el rey Nimrod [3:59]

27 - Adio, querida [3:01]

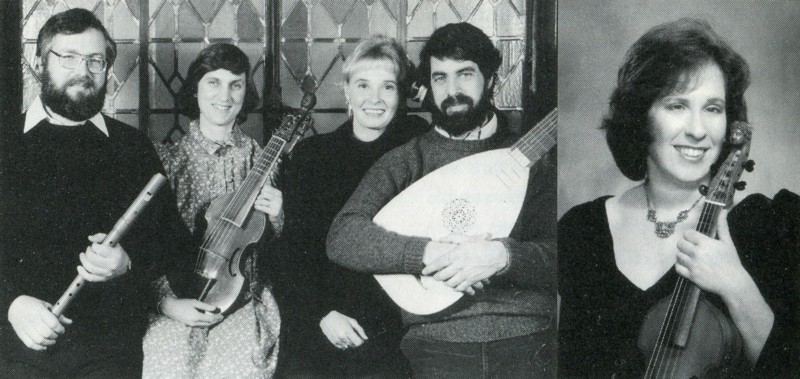

La Rondinella

Alice Kosloski, alto

Paul Bensel, recorder, crumhorn, percussion

Howard Bass, lute, guitar, harp, percussion

Rosalind Brooks Stowe, treble viol, vielle, percussion

Guest artist:

Tina Chancey, treble viol, vielle, rebec, kamenj, recorder,

percussion (#3, 4, 10, 16, 18, 21, 22, 26)

Paul Bensel, Rosalind Brooks Stowe, Alice Kosloski, Howard Bass / Tina

Chancey

THE SONGS ON THIS RECORDING DERIVE FROM a tradition that is centuries

old. Passed down through the generations, these songs are links in a

chain that connects the Jews known as Sephardim to Spain, from which

they were expelled in 1492.

Sepharad is a Hebrew word indicating Spain or the Iberian

Peninsula, where Jewish culture had thrived since the time of the Roman

empire. When the Jews left Spain, only the wealthiest could take their

possessions with them; most people took little more than they could

wear or carry. But the power of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella could

not strip them of their unwritten culture. The language of many

Sephardim is called Ladino, Judezmo, or Judeo-Spanish. It is in

Ladino that the songs on this recording are sung. This language has

attracted the interest of scholars because it preserves aspects of the

Spanish language as it was spoken in the 15th century. Of course,

Sephardic Jews added words from the new lands they inhabited, and

Hebrew words appear with some frequency. In some countries they adopted

the local language. Overall, however, the language spoken by most

Sephardic Jews has not changed much from the days when Columbus set

sail.

When the Edict of Expulsion was handed down by Ferdinand and Isabella

in March 1492, the Jews of Spain were given four months to prepare for

exile. Thus ended fifteen centuries of Jewish settlement. Jewish

culture flourished in Spain, intellectually, artistically, and

materially. Under Moslem rule especially, Jews had the freedom to

pursue a variety of professions and intellectual pursuits. However, as

the Spanish began to drive out the Moorish rulers, distrust and hatred

of non-Christians increased throughout the land. By the late 14th

century, pogroms, massacres, forced conversions, confiscation of wealth

and property, and increasingly restrictive laws began to affect Jewish

communities throughout Spain. Jews in significant numbers converted to

Catholicism, only to find themselves confronted by the Inquisition,

established in the mid-15th century to seek out and destroy heresy.

Many conversos (converted Jews) were accused of practising

Judaism in secret. Eventually, large numbers of conversos lost their

rights and property. Thousands were humiliated and tortured. Thousands

more were executed.

In early January 1492, the Moors were driven from Granada, their last

stronghold on the Iberian peninsula. The Edict of Expulsion followed in

March. Scholars disagree about how many Jews left Spain; the numbers

range from 50,000 to 300,000. Where they went is easier to determine.

Some simply crossed the border to Portugal, from which they were

subsequently expelled in 1497. Others travelled northward to England

and the Netherlands (at the time ruled by Spain), but many more

dispersed throughout the Mediterranean region. Sephardic communities

were established in North Africa, where they remain to this day. The

Moslem rulers of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco continued the

enlightened policy of peaceful coexistence they had practiced on the

Iberian peninsula. Known as convivencia, this policy is still

in effect under 20th-century rulers like King Hassan II of Morocco.

Farther east, the Ottoman Empire was particularly receptive to the

Sephardim, who settled in Turkey, the Balkans, Greece, Egypt, and

Palestine. These communities flourished in relative security until well

into this century. Thousands of Sephardic Jews living in southern

Europe perished in the concentration camps of Hitler's Germany. While

remnants of these communities still exist, many Sephardic Jews

immigrated to North and South America, and, Of course, to Israel.

In exile Sephardic Jews have clung to aspects of their Hispanic

culture, a connection strongly maintained through language. Liturgical

and secular songs played an important role in the preservation of

Ladino, and kept alive memories of historical events that otherwise

might have been forgotten. It may become apparent, as you peruse the

translations of these songs, that many of them express a woman's point

of view. Andrés Bernáldez, a Spanish monk who observed

the exile of Spanish Jews, wrote the following account that highlights

the important historical role that women played in preserving the song

tradition: "They were abandoning the land where they were born. Small

and large, young and old, on foot, atop mules or dragged by wagons,

each one followed his own route toward the chosen port of departure.

They stopped by the side of the road, some collapsing from exhaustion,

others sick, others dying. There was not a person alive who could not

have pity for these unfortunate people. Everywhere along the road they

were begged to receive baptism, but their rabbis told them to refuse, while

urging the women to sing and play tambourines to keep their spirits up."

What you will hear on this recording, therefore, are lullabies, love

songs, and narratives preserved primarily by Sephardic women in lands

throughout the Mediterranean. Women must have composed many of them as

well. Some of the songs refer to historical or Biblical events. "Cuando

el rey Nimrod" deals with the prophecy of the hunter-king who foresaw

the coming of Abraham. "Partos trocados" hints at legends surrounding

the birth of Moses. "Seu shearim," heard here instrumentally, is sung

during the holidays of Simchat Torah and Rosh Hashanah. Most of these

songs, though, are secular love songs and lullabies. The evocative "Dos

amantes tengo la mi mama" is a song of courtship, and "Scalerica de

oro" represents the wedding song tradition, a vital part of the

Sephardic repertoire. Even in a lullaby, though, Jewish elements can

sometimes be detected, as in the song "Durme, durme, hermozo hijico."

The line "You will go to school and study the law" surely refers not to

civil law but to the noble Jewish scholarly pursuit of knowledge of the

Talmud, which contains the laws by which devout Jews must live.

In the early years of the 20th century folklorists and

ethnomusicologists began to seek out and record traditional songs and

tunes of their countrymen: Cecil Sharp in England, Béla

Bartók and Zoltán Kodály in Hungary, John Lomax in

the United States. In Sephardic communities it was Manuel Manrique de

Lara who, between 1911 and 1916, was the first to make an extensive

study of this repertoire. He collected over 2000 texts and 400 tunes,

preserving many songs that might otherwise have disappeared. Many

scholars have followed in Lara's footsteps, and it is from anthologies

published by these collectors that we have developed our arrangements.

As in any folk-song tradition, especially one as widespread as

Sephardic song, there are many variations in tunes and texts. In "Los

bilbilicos cantan," for example, our version uses a Hebrew word, neshama,

soul, where other versions employ the Spanish term, alma. There

were also regional differences in singing styles, and in the manner of

accompaniment. We don't know if instruments were used at all to

accompany the singing prior to 1492, or even in the centuries that

followed. A mother singing a lullaby most likely sang without

instrumental accompaniment. A group of people singing together,

however, probably would have used whatever instruments came to hand,

and would have sung in harmony. Earlier in this century among the

Sephardim of Bosnia, for example, the accordion was very popular. In

Turkey and North Africa, the oud (Arabic cousin of the lute) was likely

to have been used.

We make use of wind instruments, bowed strings, plucked strings, and

percussion to accompany the vocal lines. We have chosen to play some

songs as instrumental pieces. The instruments are mostly ones that

would have been familiar to European people of the 15th and 16th

centuries. The wind instrument family is represented by recorders

ranging in size from the soprano to bass, and by the crumhorn (heard on

"Esta Rachel" and "Scalerica de oro"). The crumhorn is a capped, double

reed instrument that falls into the category known among early

musicians as "the buzzies." The bowed strings heard here are the treble

viol, a common court instrument of the high Renaissance, and its

medieval counterparts, the vielle ("Ir me quero") and the rebec

("Puncha, puncha" and "Una matica de ruda"). The most unusual bowed

string is the kamenj, a slender, box-shaped instrument with four

strings. This sort of instrument was known in the ancient Islamic world

and also in the Black Sea and Balkan regions. Its nasal sound can be

heard on "La prima vez" and "Noches, noches." The lute, one of the most

popular instruments of the 16th century, is featured on "Una pastora"

and "Ir me quero," and it shares about equal time with a standard,

nylon string classical guitar for the accompaniments. A small, lap-held

Gothic harp, medieval descendent of King David's version, was used in

"Esta montaña" and "Partos trocados."

Whether any of the songs on this recording date from the time when Jews

lived freely in Spain is unknown. Nor can anyone say with certainty how

Spanish Jews performed their songs. Sephardic music has joined the

"singing stream" of folk tradition, and folk music is not static,

especially one preserved for so many centuries and in so many lands.

The five hundredth anniversary of the expulsion has brought new

attention to Sephardic song and, like many early music ensembles, our

imagination has been fired by this exquisite music. Plucked and bowed

strings, recorders, and percussion instruments like the ones we use

were part of the musical heritage on the Iberian Peninsula, in the

royal courts and among common people. It seems at least possible that

they were used in Jewish communities as they were in the courts of

Spanish nobility. We hope that the interpretations offered here reflect

something of the spirit that has sustained Sephardic communities and

kept this tradition alive for more than half a millennium.

— Howard Bass