medieval.org

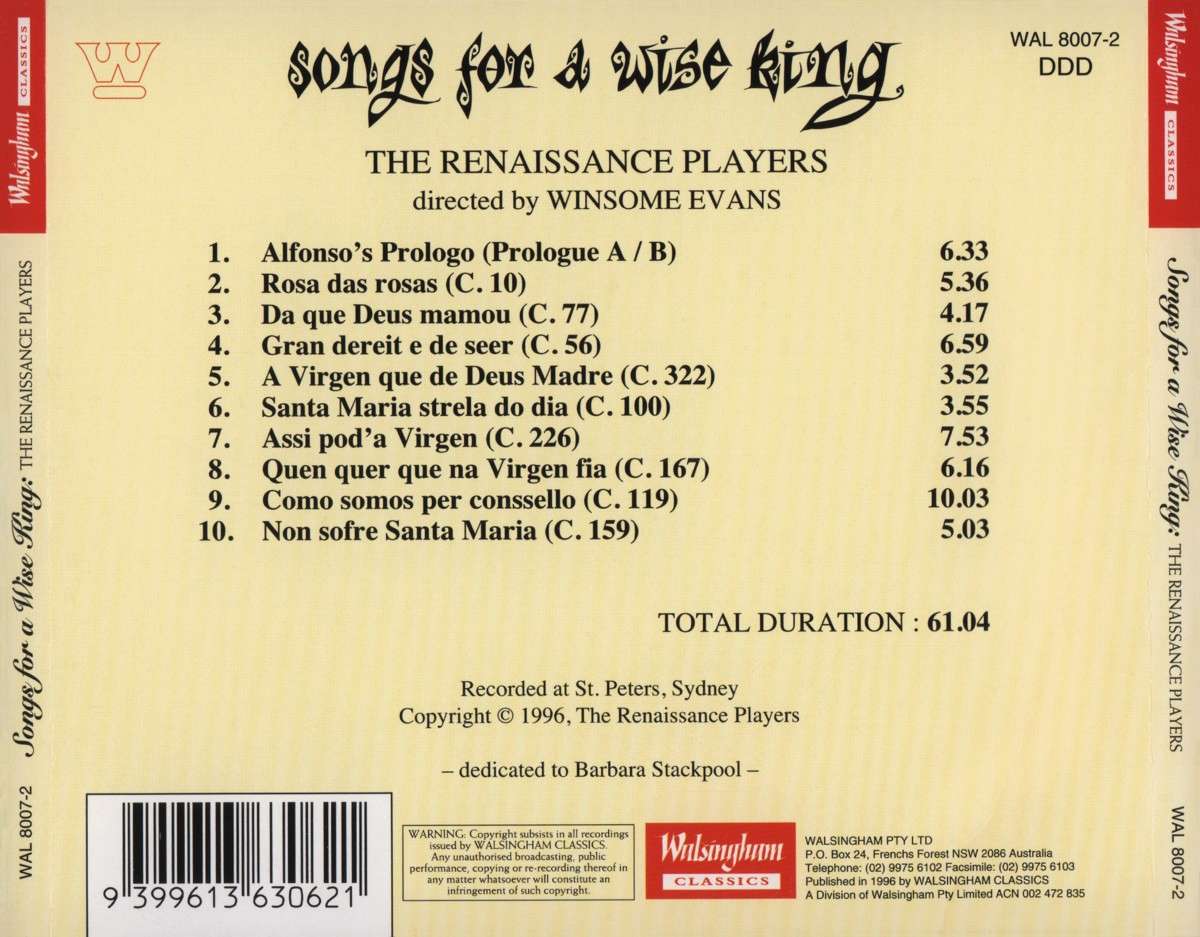

Walsingham WAL 8007-2

1996

Songs for a Wise King / The Renaissance Players

Cantigas de Santa Maria I

medieval.org

Walsingham WAL 8007-2

1996

1. Alfonso's Prologo (A / B)

1. Alfonso's Prologo (Prologue A / B) [6:35]

t: Presentación / Prólogo — m: CSM 1

Geoff Sirmai, reader (in English) Prologue A / B | Winsome Evans, harp CSM 1

2. Rosa das rosas [5:40]

CSM 10

Mara Kiek, alto | Llew Kiek, bouzouki | Winsome Evans, bowed diwan saz

3. Da que Deus mamou [4:21]

CSM 77

Winsome Evans, shawms (2), gemshorns, organetto, harp |

Katie Ward, vielle | Benedict Hames, rebec, gemshorn |

Andrew Tredinnick, mandora | Llew Kiek, gittern |

Ingrid Walker, whistle, gemshorn | Barbara Stackpool, castanets, finger cymbals |

Jenny Duck-Chong, bells | Andrew Lambkin, darabukka

4. Gran dereit e de seer [7:05]

CSM 56

Chorus | Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano | Mina Kanaridis, soprano

Winsome Evans, psaltery | Andrew Tredinnick, ud |

Katie Ward, vielle | Benedict Hames, bowed diwan saz |

Barbara Stackpool, tambourine | Andrew Lambkin, bells

5. A Virgen que de Deus Madre [3:57]

CSM 322

Winsome Evans, organetto | Ingrid Walker, whistle |

Katie Ward, vielle | Andrew Tredinnick, mandora |

Llew Kiek, gittern | Jenny Duck-Chong, tambourine |

Barbara Stackpool, castanets | Andrew Lambkin, darabukka

6. Santa Maria strella do dia [4:02]

CSM 100

Chorus | Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano | Mina Kanaridis, soprano | Mara Kiek, alto, tapan

Winsome Evans, bombarde, shawm, bells |

Ingrid Walker, whistle | Katie Ward, vielle |

Benedict Hames, rebec | Andrew Tredinnick, mandora |

Llew Kiek, gittern | Barbara Stackpool, finger cymbals

7. Assi pod'a Virgen [7:55]

CSM 226

Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano | Mina Kanaridis, soprano | Mara Kiek, alto

Chorus | Winsome Evans, harps (2) |

Andrew Tredinnick, chitarra moresca | Andrew Lambkin, daireh

8. Quen quer que na Virgen fia [6:19]

CSM 167

Winsome Evans, harps (2)

9. Como somos per conssello [10:07]

CSM 119

Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano | Chorus

Winsome Evans, shawm | Ingrid Walker, whistle |

Katie Ward, vielle | Andrew Tredinnick, mandora |

Barbara Stackpool, castanets | Andrew Lambkin, darabukka

10. Non sofre Santa Maria [5:06]

CSM 159

Chorus | Mara Kiek, alto, daireh | Geoff Sirmai, reader

Winsome Evans, shawms (3) | Andrew Tredinnick, mandora |

Katie Ward, vielle | Benedict Hames, rebec | Ingrid Walker, whistle |

Barbara Stackpool, castanets | Andrew Lambkin, tapan

Alfonso X and the Cantigas

Marian cult

Performance

The Renaissance Players | credits

In the first of the two parts of the Prologue preceding the main body of cantigas,

Alfonso outlines those principalities of Northern and reconquered Spain

as well as places beyond the Iberian Peninsula to which he considered

he could claim kingly birthright. In the second part he declares his

intention to become a trobador for the best lady of all, the

Virgin Mary, to whom alone he will devote his poetry. The text is

declaimed and, in a biblical gesture reminiscent of King David's

“joywood”, is accompanied by the harp.

Count Afonso Sanches and

his brother Pedro, two of the illegitimate sons of Dinis (the sixth king

of Portugal and grandson of Alfonso X), were amongst the many

distinguished poets who gathered at the Portuguese court. It has been

noted that in one of his love poems Afonso Sanches expresses exactly

the same sentiment, in slightly different words, as that found in the

third stanza of me second part of the Affonsine Prologue, possibly as a

tribute to his great-grandfather. The difference is that, unlike the

Virgin Mary, his lady rejected him:

“I have lost her who was the best thing who God made and however much I served her I nevertheless lost her”.

The main melody, when played, is in the aeolian mode; most of the harp part is improvised.

2. Rosa das rosas (C.10)

This is the second cantiga de loor, in Alfonso's collection (the first being cantiga 1 which describes the seven sorrows and joys of Mary). As the first cantiga with the final number X (symbol of Christ), it thus starts the first complete cyclic pattern of one cantiga de loor followed by nine cantigas de miragre. The cantigas de loor as a genre are related to paraliturgical hymns which were often processional. The last stanza of this cantiga is not performed here (though printed below) because it repeats the sentiments of the Prologo where they were more fully expounded.

It is sung here in the mysterious chest voice reminiscent of that used in cante jondo

and still heard in various forms of Andalusian-Arabic-Judaic music in

North Africa and the Mediterranean Basin. The stanzas are sung in free

rhythms with increasing intensity and ornamentation, while the refrains

are in regularly measured rhythms. While we have not attempted to

reproduce literally the instruments depicted in the manuscript's mast

-head illumination (plucked gittern and bowed vielle), we have decided

to follow its concept by accompanying the singer with two baglamas. one

plucked and one bowed. The plucked baglama takes the main instrumental

role and acts as the singer's counterfoil, echoing and developing her

end-of-phrase ornaments.

The mode is dorian with two sixths, minor and major.

3. Da que Deus mamou (C. 77)

This is an instrumental rendition of a cantiga

which tells of a miracle performed by the Virgin Mary at Lugo which is

situated near Triacastela in Galicia, north of the famous pilgrim road

to Santiago de Compostela. The piece is used to demonstrate a

large-scale instrumentarium, in which the stanzas are played by small,

homogeneous or paired groupings (plucked strings, bowed strings, horn

recorders or gemshorns, shawms, organ plus bells) and the refrains by

the full, mixed ensemble.

The idea for this motley ensemble, out

of which smaller groupings take their turn to play the stanzas, derived

not from the depiction of the twenty-four Elders playing varieties of

bowed and plucked stringed instruments wonderfully sculptured around the

Portico de la Gloria of Santiago Cathedral (which Phil Pickett has used

as the basis of some of his instrumental renditions of Alfonso's cantigas), but from the description of pilgrims assembled from all over Europe for the feast-day vigil of Santiago found in the Liber Sancti Jacobi (now known as The Pilgrim's Guide), the fifth book of the 12th century Codex Calixtinus. The pilgrim crowds singing, playing and dancing around the altar include Teutons, Franks, English, Greeks, “barbarians... and other tribes”, that is, “various people from every climate of the world”

and they sing “to the accompaniment of harps, lyres, tambourines, bone

flutes, shepherds' pipes, reed pipes, straight metal trumpets, vielles,

rotas of Brittany and Gaul, and psalteries”.

4. Gran dereit e de seer (C. 561)

This rose-bush miracle is related to cantiga 24 which recounts the legend from Chartres about “how Holy Mary made a flower similar to a lily grow in the mouth of cleric after he died”. Interestingly, its text finishes with the congregation of living clerics going off to dance after the sermon of thanksgiving.

In cantiga

56, a rose-bush with five roses on it appears in the mouth of a devout

monk soon after his death. The fourth stanza cites a list of the five

texts the monk had recited in her honour, each of which started with a

letter in Mary's name (but not in the exact order of the letters of

“Maria”). All of these are psalms and include the Magnificat, whose full title from the Latin Vulgate is Magnificat anima mea Dominum

(“My soul doth magnify the Lord”). This is the Virgin's hymn of praise

at the Annunciation (found in Luke 1:46-55), which is usually sung at

Vespers.

The melody of this cantiga is in the hypo-ionian

mode. Various types of plucked and bowed stringed instruments and bells

accompany the text which is sung in measured and unmeasured rhythms or,

to heighten the drama, declaimed against instrumental drones and

improvised melodic filigree.

5. A Virgen que de Deus Madre (C.322)

5. A Virgen que de Deus Madre (C.322)

This is the second of the three instrumental renderings of cantiga

melodies in this CD set. It is played as a discreetly joyful dance in

honour of the Virgin Mary who, in the text, had restored to life a man

who had suffered a terrible death. The plucked and bowed stringed

instruments play the melody in only the tutti sections (i.e, the

first and fourth) along with the organetto and whistle. The latter pair

of instruments play the two stanzaic sections — firstly improvising

decorations on the main melody (as given in the manuscript) and then

improvising completely new melodies or counter-melodies in the allotted

time span of the stanza's melody.

The melody is in the dorian mode and is played with major and minor sixths.

6. Santa Maria strela do dia (C. 100)

There seem to be certain mnemonic icons at play in the structures and numbers of this, the centesimal cantiga, and the tenth cantiga de loor

in the X series. Its Roman number C may suggest the last uncial of the

Greek spelling of Christ. It is structured with a trinity of stanzas and

a septenary of refrains and stanzas. The melody is structured into ten

units, if refrains are sung at the beginning and end of each of its

three stanzas. Our after-dance, which represents the dance following the

recessional after the sermon, as described in cantiga 24, reiterates the ten-fold segmentation.

The text is a gloss on the hymn Ave maris stella composed by the 6th century poet-bishop Venantius Fortunatus (author of the wondrous Holy Cross hymns Vexilla regis prodeunt and Pange lingua). Mary is addressed as “Strela do Dia” (Star of the Day) in the refrain to this cantiga, and also in that of cantiga 325 (where she is described as “the one who gives guidance on sea and land”). Likewise, in Polorum regina, one of the dance-songs in the Catalonian Llibre Vermell, she is addressed as “Stella Matutina” (Morning Star). In 1272 Alfonso X founded the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary with the star as its emblem.

The

melody is in the dorian mode, sung by the chorus in the refrains and

soloists in the stanzas, and accompanied by a joyously motley pilgrim

ensemble.

7. Assi pod' a Virgen (C. 226)

One of the 21 cantigas

dealing with churches and monasteries, this is a miraculous tale of the

sunken monastery in “Ingraterra” / “Gran Bretanna” which arose on

Easter Day (like God), exactly one year after it had disappeared into

the earth. Though by no means the same tale, it may be a variant on the

Celtic legend, c. 400 AD, about the submerged Cathedral of Ys in

Brittany (which was Claude Debussy's inspiration for his piano piece La cathédrale engloutie).

It apparently sank into the sea as punishment for the wicked behaviour

of its inhabitants and arose again from time to time at sunrise to curb

and warn against further misdeeds.

In order to preserve the enjambements

of text across the stanzas (particularly from stanzas 8 to 9 and 12 to

13), the refrain is not sung after every stanza but only after stanza 6

and, to give the whole a cyclic structure, at the beginning and the end

of the piece. The cueing melodies which lead into the refrain are

exactly the same each time, and the stanzas are sung or declaimed by a

solo voice (with harp doubling or improvising), or by three voices using

drone-harmonies (plus two harps and chitarra moresca).

The melody is in the mixolydian mode and is rhythmicised in triple metre with hemiola accentuation.

8. Quen quer que na Virgen fia (C. 167)

This is one of the six cantigas

in which the Virgin Mary comes to the assistance of Muslims or Jews.

The text, which is not sung here, tells how a Muslim woman from Borja in

Saragossa was converted to Christianity. She had carried her dead son

to the shrine of Holy Mary at Salas and, after three days, he was

resurrected at Mary's intervention.

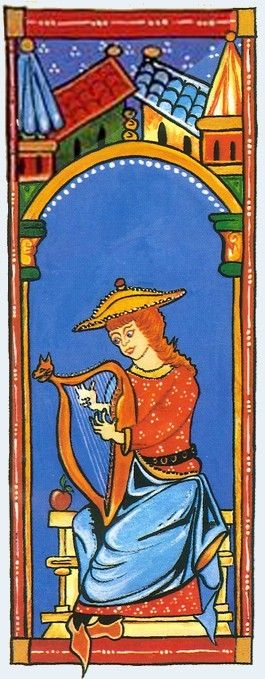

This the third instrumental rendering of a cantiga

melody in this CD set, and the first of such played by a pair of

identical instruments. The idea to use lap-harps was taken from the

illumination at the head of cantiga 380. In this the social

status and race of the two harp players are difficult to determine —

with their long, curly auburn hair on head and face, bejewelled with

helmets”(possibly pilgrim hats?) and voluminous shoulder-fastened

cloaks. This is one of the few illustrations in this manuscript (b.1.2)

to feature a representational background rather than the Mudejar-style

patterned texture of the others. The players sit under a double arch

above which rooftops and minaret-like turrets are shown.

In our

arrangement, the first harp player improvises a long prelude to

introduce the mode and the metre of the refrain melody which is rendered

in triple time with end-of-phrase hemiolas. The melodies of the stanzas

are played alternately in free-moving-into-measured rhythms, or are

entirely measured. There is much decorative improvisation between

stanzas. For example, the two harps simultaneously improvise cueing

melodies of appropriate length in measured rhythms, as well as

free-measured interludes between stanzas.

The melody is in the mixolydian mode.

9. Como somos per conssello (C. 119)

This is one of eleven cantigas

in which the Virgin Mary sets free those who ask for her assistance

when being persecuted by devils. In this case, she rescues a corrupt

judge and then gives him one day's grace before he dies in which to make

confession to a priest.

The instrumentation in this piece (and also in cantigas 100 and 159) is based on that still used today in the popular cobla

bands all over Spain from Galicia to Catalonia (guitars, one-man

whistle and drum, two or three shawms), to which the vielle is added. In

our arrangement, the instruments provide the improvised prelude and the

short, dance-like postlude, as well as various types of interludes

(known today as falsetas) both between stanzas and as pre-learnt cues before refrains. Both instruments and voices add extempore ornamental graces and passage-work to the main and cue melodies.

To

heighten its drama, the main text is presented in three ways — sung in

regular metre, in free rhythm or declaimed. Although there are fourteen

stanzas the refrain is sung only four times: at the very beginning and

the end, as well as after stanzas 1 and 8. It is also played once by

instruments alone, between stanzas 12 and 13, as a melodic mnemonic of

its text and to make the change-over to the events that followed the

Virgin Mary's speech. Thus stanzas 2—8 and 9—12 are continuous, sung

or spoken in free rhythms.

The main melody is in the dorian mode

and, when measured, is set in 2+3 patterns against cross-accented 3+2

in percussion parts, as is still found in the charrada of Castile, Leon and Extremadura.

10. Non sofre Santa Maria (C.159)

Narrated “as-I-heard-tell” in the third person, this is one of several cantigas

which concern the misadventures which befell pilgrims in foreign towns

(such as Soissons) or far from home (Santiago de Compostela). The

reformed monastery of Cluny was primarily responsible for setting up and

managing the pilgrimages to Santiago which, by the 13th century, was

already established for Christians as the third great pilgrim shrine

after Jerusalem and Rome. From the 12th century on, an influx of French

Cistercian monks (wbo adhered in a more austere way to the same Rule of

St Benedict as the Cluniacs) came to settle in Northern Spain in order

to assist in the spiritual Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula. They

encouraged pilgrims to travel to other shrines beyond the border, such

as the Church of Saint Mary of Rocamador in Southern France which had

been given grants of land in the Peninsula by grateful Christian Iberian

kings. From Rocamador there survives yet another factor which links it

with Alfonso's spiritual lyrical venture. This is the anonymous prose

collection of Marian pilgrim miracles, the Liber miraculorum Sancta Mariae de Rupe Amatoris, which mostly follows the themes of Gauthier de Coincy.

Pilgrims

were distinguishable by their dress — the long, coarse, sleeved runic,

the pouch and the tall, stout staff as well as various kinds of

protective headgear — all of which were blessed before departure. For

the return journey, as proof of having completed the pilgrimage, they

then attached a badge or token to their bag or has (for example, a palm

from Jericho, or a cockle-shell from Compostela). The illuminations in

the T.j.1 manuscript to cantiga 159 show the pilgrims in their

various hats, wearing plain garments and carrying staffs but without

pouches (having already arrived and taken them off): likewise, in the

illumination for cantiga 49 (Ben com' aos van per mar),

the more ornately dressed, lost pilgrims bear their staffs and wear

their waist-pouches as they are still out on the road being guided by

Mary to her church at Soissons.

As there is a discrepancy between the number of pilgrims described in the text of cantiga

159 (nine) and the number shown in the cartoon illuminations in T.j.1

(eight or nine), we decided to take a little poetic licence here and

change the number of pilgrims to “ten” — on the basis that X is a

significant number in Alfonso's arrangement of the two cantiga genres (de loor and de miragre); and this is the tenth cantiga in this recorded set, which started with cantiga 10, and is performed by ten musicians!

The stanzas are sung solo (with the same mysterious vocal quality as our first cantiga,

number 10) in measured and unmeasured rhythms, or against drone

harmonies. The refrains themselves, which do not occur after every

stanza, are structured in a triptych arrangement. Firstly, the text is

sung and played tutti, then repeated by instruments alone and

thirdly followed by e new, prelearnt coda — a pattern maintained until

the postlude. The instrumentation is based again (like cantigas 110 and 119) on the cobla instrumentation.

The melody is in the mixolydian mode, with a piquant start on the supertonic, and has been transcribed into 2+2+3 rhythms.