medieval.org

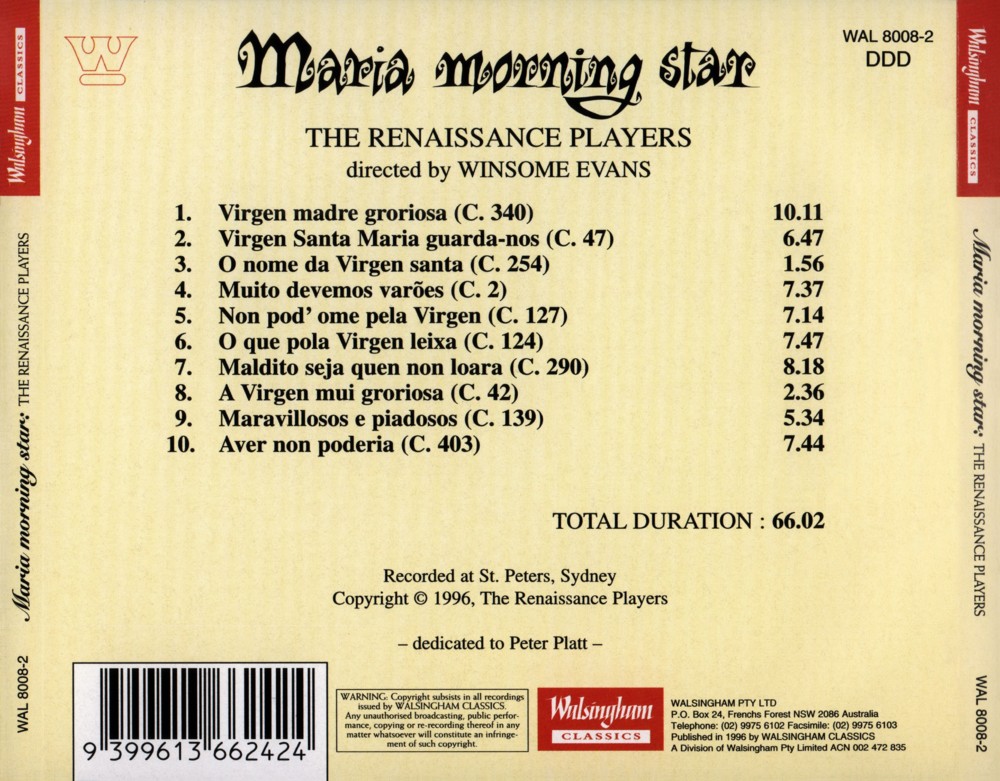

Walsingham WAL 8008-2

1996

Maria Morning Star / The Renaissance Players

Cantigas de Santa Maria II

medieval.org

Walsingham WAL 8008-2

1996

1. Virgen madre groriosa (C. 340)

1. Virgen madre groriosa [10:13]

CSM 340

Mina Kanaridis, soprano | Tobias Coler, counter-tenor

Winsome Evans, bells

2. Virgen Santa Maria guarda-nos [6:49]

CSM 47

Chorus | Geoff Sirmai, reader

Winsome Evans, sinfonye, psaltery | Katie Ward, vielle | Benedict Hames, rebec |

Andrew Tredinnick, ud | Barbara Stackpool, finger cymbals | Andrew Lambkin, daireh

3. O nome da Virgen santa [1:59]

CSM 254

Winsome Evans, whistle | Benedict Hames, whistle |

Katie Ward, vielle | Andrew Lambkin, darabukka

4. Muito devemos, varões [7:39]

CSM 2

Mina Kanaridis, soprano | Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano

Winsome Evans, organetto | Katie Ward, vielle | Benedict Hames, rebec |

Andrew Tredinnick, gittern | Barbara Stackpool, finger cymbals | Andrew Lambkin, daireh

5. Non pod' ome pela Virgen [7:14]

CSM 127

Winsome Evans, harp, psaltery | Andrew Tredinnick, gittern |

Llew Kiek, citole

6. O que pola Virgen leixa [7:48]

CSM 124

Mina Kanaridis, soprano | Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano | Tobias Cole, counter-tenor

Winsome Evans, sinfonye | Andrew Tredinnick, chitarra moresca |

Barbara Stackpool, castanets | Andrew Lambkin, daireh

7. Maldito seja quien non loara [8:23]

CSM 290

Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano | Mara Kiek, alto

Winsome Evans, harp | Ingrid Walker, gemshorn | Katie Ward, vielle

8. A virgen mui groriosa [2:38]

CSM 42

Winsome Evans, whistles (2) | Andrew Lambkin, tabors (2)

9. Maravillosos e piadosos [5:36]

CSM 139

Chorus | Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano

Winsome Evans, organetto | Ingrid Walker, whistle |

Katie Ward, vielle | Andrew Tredinnick, chitarra moresca |

Barbara Stackpool, castanets | Andrew Lambkin, darabukka

10. Aver non poderia [7:44]

CSM 403

Chorus | Jenny Duck-Chong, mezzo-soprano, tambourine

Winsome Evans, organetto, treble shawms (2) | Ingrid Walker, whistle |

Katie Ward, vielle | Benedict Hames, rebec | Andrew Tredinnick, ud |

Barbara Stackpool, finger cymbals, castanets | Andrew Lambkin, daireh, darabukka | Mara Kiek, tapan

Alfonso X and the Cantigas

Instrumentarium

The Renaissance Players | credits

This is one of nine cantigas which appears twice in manuscript b.1.2, first as 340 and later as 412. The last word of each of the seven stanzas of this cantiga de loor is "alva" (dawn) and the first three words for each of the six complete stanzas are "Tu es alva",

thus identifying this as a sacred dawn song, a sort of summons to

worshipful prayer and devotion. It has several possible conceptual

precedents — for example, the Christian Latin, religious dawn-hymns,

dozens of which survive from at least as early as the 9th and 10th

centuries. Extracts from Ales diei nuntius, a religious hymn by Prudentius (4th century), contain images which relate to cantiga 340:

"...when

dawn has sprinkled the sky with her shining breath she may strengthen

all those who have carried out their work and give them hope of light...

Gold, pleasure, joy, riches, honours, successes, all those evil things

that puff us up — when morning comes, they are all nothing."

According to Hans Spanke, the melody of cantiga 340 is much the same as the one used in the secular alba (dawn song) S'anc fuy bela ni prezada

by the early 13th century troubadour Cadenet. Hendrik van der Werf

makes two further points relating to the structure and the melody.

Firstly, the rhyme scheme and the rhyme sounds in cantiga 340 are the same as in Cadenet's alba

; and secondly, the melodic contours of some (but not all) of the

internal phrases are similar to those found in the well-known alba Reis glorios by the 12th century troubadour Guiraut de Borneil (who finishes each stanza with a single, recurring, refrain line — "Et ades sera l'alba").

In other Alfonsine cantiga texts Mary is called "the morning star" (strela do dia) or "the star of the sea" (strela do mar),

that is, the star which heralds dawn. In cantiga 340 Mary, the morning

star, is the dawn (see stanza 5). Given that in Christian theology God

is light* ("Ego sum lux mundi") and the Virgin Mary accepted the divine light from the angel with humility ("Ecce ancilla Domini"),

the result was the creation of the child (the Christ, God, the light)

through the union of God (heaven, divine spirit) and mankind (earth,

human flesh). Thus "dawn", that is, Mary the morning star, is the

creative bearer of light, the sun, the Christ. "Dawn" (alva) eternally gives mankind a promise of salvation.

In

our performance the melodic sections are shared antiphonally between

two solo singers (with occasional brief interludes on the bells). The

original dorian melody is unusually ornate, so its melismas (and

additional, improvised ones) are sung as ornamental flourishes. It was

found that although the cleverly structured text and the borrowed melody

matched snugly in the opening refrain and the first short stanza, this

situation did not prevail throughout. Because the musical phrases and

their overall structure often simply do not coincide with those of the

text, due to complicated enjambements within and across stanzas,

there are many performance options to be considered. For this

performance the numbers 5 and 3 were used to group the musical phrases

and text into sections.

The masthead illumination to this cantiga

in b.1.2 shows two rustics out in the country, one playing a conch

shell, also known as pilgrim shell (suggesting a completed pilgrimage to

Santiago da Compostela), the other a thin reed (?) pipe. This does not

suggest a possible instrumentation for this piece but acts as a reminder

that it was shepherds who were chosen by the angel to come to worship

at the birth of Christ in the manger, and that the lowliest and the most

humble can offer the richest devotion, for, in the words of Paul the

Deacon (8th century), "to jubilate is to cry out with a rustic voice."

* Psalms 27: 1 and 36: 9 ; John 8: 12 and 3: 19-21

2. Virgen Santa Maria, guarda-nos (C. 47)

This

quaint folk tale is found in many mediaeval sources, including the

collections of Juan Gil de Zamora and Gonzalo de Berceo. To preserve the

"shaggy-dog" fantasy we have opted for a quite different mode of

performance here. The aeolian melody is only heard in its complete form

at the beginning and the end, encircling a somewhat modified version of

the original text which is declaimed against psaltery improvisations. In

these boxing-in sections (the prelude and postlude), the instruments

play the whole of the simple, virelai melody (structured A1 A2 a2 a2 a1 a2 A1 A2), joined in the refrains by the voices singing in organum. As the melody is quite mordant in its avoidance of the tonic until the end of the closed cadence (A2),

it has been realised in a "wilishly devilish" way in a pattern of

additive rhythms which allow the text to flow in seeming serenity.

3. O nome da Virgen Santa (C. 254)

This cantiga and the previous one, Virgen Santa Maria guarda nos (C. 47), are two of five cantigas which deal with the Virgin's power to liberate those taunted by the devil and his minions. In O nome,

set in France, the assault is made against two monks who run off from

their monastery to avoid being beaten. As they spend the day on the

river bank telling bawdy and licentious tales they are confronted by a

little boatful of foreign demons. Terrified, the monks call on Holy Mary

for forgiveness and rescue so they can return home.

The text of this cantiga is not sung, but played instrumentally as the first of three instrumental cantigas

on this CD (a pattern established throughout our series). The structure

of its ionian mode melody is built up economically with a series of

very small musical "bricks" to make a simple virelai — A1 A2 A1 A3 b1 b2 b1 b2 a1 a2 a1 a3 A1 A2 A1 A3,

and is rhythmicised in triple time with regular hemiola crosspatteming.

The darabukka is played to sound in its down-beats a little like the zambomba, a friction drum still used throughout Spain in Christmas festivities.

4. Muito devemos varões (C. 2)

This cantiga

is one of twenty-eight which deal with gifts given by the Virgin Mary

to those who espouse her cause. Set in 7th century Toledo, it refers to

actual people from Spain's Visigothic past, namely : Saint Ildefonso,

the Archbishop of Toledo famous for his opposition to those who doubted

the Virgin Mary's virginity; King Reccesvinth, the 28th king of the

Visigoths (who ruled from 653 - 672); Saint Leocadia, the patron saint

of Toledo (who died in prison in 304 AD) and "Don Siagrio", also known

as Sigiberto or Siseberto, who succeeded Ildefonso as Archbishop. It

also focuses on a particular alb, the clerical vestment symbolic of

purity. This was a white linen robe (its name refers to its white

colour) with close-fitting sleeves which was worn by the officiating

priest. Being a "rare and beautiful gift" (stanza 5), Mary's alb was

probably decorated with embroidery on the hem, neck and wrist-cuffs,

possibly also with the additional four or five rectangular patches of

embroidery called apparels, parures or orphreys.

Variants of this miracle are found in many sources from the 8th century on, including Alfonso X's own Primera Cronica General. One would expect that this, the first cantiga de miragre

in Alfonso's carefully planned collection, would deal with an important

person or event relating to the Virgin Mary. This exptectation is

confirmed and achieved by the establishment of a link over the centuries

between an outstanding religious "Alfonso" (or variously, "Alifonsso", as the cantiga text names Ildefonso) and the living, secular king Alfonso making his own testament to Mary's glory with his Book of cantigas de Santa Maria.

Not only did these great men both defend the Virgin Mary's honour and

(according to King Alfonso's text) share the same name, but there was

also a further strong factor in the king's reasoning, namely, their

mutual connection with Toledo, the capital of the Visigothic kingdom and

the primary see of the Spanish church. Toledo had been under Muslim

rule for three centuries until its reconquest in 1085. Already famed as a

seat of culture and learning during the Muslim Ummayad and Almoravid

dynasties, it was still, in the reign of Alfonso X, a great, flourishing

city ever enriched by his tolerance of the relatively peaceful

cohabitation of substantial groups of Christians, Jews and Muslims.

Apart from the short improvised prelude, the whole of this cantiga

is performed in measured rhythms (patterned in additive groups of 6, 4

and 3). The melody is in the ionian mode and structured as a virelai (ABcca+bAB, where c melodies are actually b melodies but with the A incipit).

The refrain, sung by two voices, occurs at the beginning and the end,

and before the dramatic text of the last stanza. Otherwise the stanzas

run on into one another with interludes of various lengths improvised or

cued between them.

5. Non pod' ome pela Virgen (C. 127)

This is the second of the instrumentally rendered cantigas

on our CD. It is one of twenty-six concerned with punishment and

forgiveness meted out to devotees of Virgin Mary. The text (unsung)

tells of a young man from Puy in Southern France who loses a foot and

has it restored miraculously. As punishment for hitting his mother he is

not allowed into church, even when, as penance, he goes on pilgrimage.

When he comes back, however much he pushes he still cannot get into his

home church. He is advised that possibly he could get in if his foot

were cut off. When his mother sees him after the deed is done, she

appeals to the Virgin. The statue of Mary tells her to take her son's

foot in her hand and put it back on his leg. This miracle is immediately

celebrated in the church by the priests who, after the "amen", order all the bells to ring.

The mixolydian melody (a virelai structured A1 A2 b b a1 a2 A1 A2)

is played by four different plucked string instruments. In the

interludes between stanzas each instrument takes turns at offering

improvisation, sometimes imitating and extending, sometimes presenting

new motives and textures. The refrain melody is occasionally doubled in

organal fifths, likewise the stanzaic a1 a2.

6. O que pola Virgen leixa (C. 124)

The gruesome tale recounted "as I heard tell"

in this cantiga takes place in Andalusia in land still under Muslim

rule near the Strait of Gibraltar ("near both seas"). The precise

location is not stated but the events befall a man who frequently

travelled to Moorish Jerez and Seville and had his beard trimmed off in

Alcala de Guadaira. It is one of twenty-four cantigas in the

"captive and condemned" category. Although the Virgin Mary does not

actually appear or speak in this text, there are three clear signs of

proof that she did hear the Christian man's plea and confession during

his death-torture (by stoning, spearing and throat-cutting). Firstly,

she keeps him alive through all of this and long enough to be allowed to

make priestly confession; secondly, his beard grows again after his

death and thirdly, no animals come to ravish his corpse.

The nine stanzas are sung to a mixolydian melody, a virelai (A B c1 c2 a b A B),

which is set in a fixed pattern of additive rhythms. Against the main

melody, the singers not only add tonic or dominant drones but also add a

third contrapuntal part producing a three-part, conductus-like,

drone-based texture. The refrain is sung only four times, cued in each

time by a pre-learnt instrumental interlude. Apart from the dying

Christian's last words, which are sung in free rhythm, the rest of the

piece is performed in measured rhythm.

7. Maldito seja quen non loara (C. 290)

The six stanzas of this cantiga de loor alternately list benedictions (Beeito seja...) and maledictions (Maldito seja...). In order to reinforce this we have chosen voices and instruments contrasting in timbre and production — the dark, cante jondo

alto against a lighter, brighter mezzo-soprano, and the richly nasal

vielle against the pure, "white"-sounding gemshorn, all linked together

by the harp (King David's "joywood").

Three stanzas are sung in

measured modal rhythms, two are sung in free unmeasured rhythm, and one

(the last) is declaimed against the measured playing of the melody on

the harp. There are three substantial instrumental sections — prelude,

postlude and interlude which, when measured, are prelearnt and, when

unmeasured, are improvised. The mixolydian melody, when measured, is

played in modal rhythm, and is structured as a virelai (A1 B a2 a2 a1 b A1 B).

The textual dichotomy of the alternating refrains may be mirrored in

the tension and release heard in the melodic motifs — for instance, all A / a motifs begin supertonic to mediant, B / b motifs begin subdominant to dominant and A1 cadences from subdominant to mediant.

8. A virgen mui groriosa (C. 42)

The illumination at the masthead of cantiga de loor 370, Loemos muit' a Virgen, suggested the instrumentation for our third instrumental rendition of a cantiga melody : two whistle-and-tabor players.

The unsung text of cantiga 42 is one of thirty-one cantigas

concerned with statues of the Virgin Mary. In this tale set in Germany,

a young man about to be married looks about for somewhere safe to place

his engagement ring to avoid damaging it in a ball game. The green

meadow where the game is being played lies next to a church in the

process of renovation. The beautiful statue of the Virgin temporarily

placed outside during the repairs catches the man's attention, and while

he puts his ring on the statue's finger he makes silly promises of

devotion. After the game, when the ring and the statue shrink, he abuses

the statue. The Virgin appears in his dreams on his wedding night,

chastises him and sends him away. He spends the rest of his life as a

hermit dedicated to Her.

The mixolydian melody (a virelai structured A1 A2 b1 b2 a2 A1 A2)

is performed with a regular pattern of additive rhythms (25 beats per

phrase : long-short, long-long-long-short, long-long-long).

9. Maravillosos e piadosos (C. 139)

There are a number of unusual aspects to this cantiga which survives in various forms in many mediaeval sources and was even the subject of a 20th century film, Marcelino, pan y vino (1952). In Valverde's categorisation of genres it is one of the thirty-one cantigas

concerned with the statue of the Virgin Mary. In this particular

version, set in Flanders, not only does the statue of the Virgin speak

to the Infant Son she cradles (as part of the statue), but also the baby

Christ speaks to the little boy who has offered him his bread.

When

the whole text (including all refrains) is set out in verse form it

makes a series of crosses on the page. Although this cruciform shape

cannot be seen in the surviving manuscripts where the text runs in a

continuous rectangular block, it may have been known to (seen in the

mind of, or on the wax tablets of) the author. Certainly the decorative

game playing involved in composing carmina figurata was known in

the Hellenistic and the Roman worlds. Publilius Porphyrius (4th century)

and Eugenius Vulgarius (10th century), for example, wrote various poems

in the shape of an altar, an organ or a pyramid. One is reminded too of

the "pattern" poems of the 17th century metaphysical English poet

George Herbert in which the lines of text form the shape of the subject —

The Altar, Easter Wings. Conceptually, these are related to but

not quite the same as mediaeval Hebrew micrography (or minute script)

where the letters themselves outline (rather than fill in) shapes (of

animals, humans, and abstract patternings).

The mode of the melody is hypo-dorian. Its virelai structure (A1 A2 b1 b2 b1 b2 a1 a2 A1 A2) is made up, unusually, of a series of sequentially patterned motifs — descending in the A / a sections and ascending in b.

All phrases begin with the same three-note ascent (tonic to mediant).

Stanzas 2 to 4 inclusive are divided in their presentation, that is,

sung in unmeasured rhythm then in measured, additive rhythms. The

refrains (which are not performed after every stanza) are sung with

drones and organal fifths.

10. Aver non poderia (C. "403"; Ms To., Cantiga 50)

The numbering ascribed to this cantiga

derives from Walter Mettman's classification. It is not found in either

of the manuscripts in the library of El Escorial, Madrid (b.1.2 and

T.j.1), nor in the Florence source. It survives only in the manuscript

from Toledo Cathedral which is now held in the Biblioteca Nacional,

Madrid (To.), where it is numbered 50. Though this would seem to

indicate a cantiga de loor, it is in fact a cantiga de dolor.

Of

its eight stanzas only the first is sung here, circling continuously

upon itself, shared between a chorus and a soloist. One of the few

cantigas constructed without a refrain, its text outlines the seven

sorrows Holy Mary suffered because of Her Son. In our spiralling singing

of stanza 1 we wish to refer back, in circular fashion, to the first cantiga de loor

(number 1) — also without a refrain — which describes the seven joys

which Mary had through Her Son. Despite the dreadful dolour evoked by

the events in the text of cantiga "403", we have tried to suggest in the postludal presentation of the melody a textless jubilus,

as a pledge of life and faith, a reminder of Her seven joys. Out of

death and loneliness comes life, and the Assumption, which will reunite

Her with Her Son, still lies ahead. In this jubilus section, the slow-moving melody, loud and solemn, is played by shawms (the triples of the cobla

band) against vigorous and lively percussion patterns on drums,

tambourine and castanets. This too is a reminder of the crowning of the

Virgin and the Feast of the Assumption and is still celebrated today in

Galicia with a joyous communal dance of men and women after the Mass on

the Feast of the Assumption (August 15).

The melody is in the mixolydian mode with tensions built into the phrase incipits and cadences (for example, the motifs start as follows : a — supertonic to subdominant, b — leading note, tonic, supertonic, and c — mediant, dominant, leading note). The overall structure is not that of a virelai, but a simple binary form made up of two sets of related motifs : A B (or, in more detailed format,a b a b c d c b).