The Cloister and the Sparrow Hawk / Tim Rayborn · Shira Kammen

Songs of the Monk of Montaudon

medieval.org

AS&V Gaudeamus 175

1998

1. Estampie 'Cor irat' [3:40]

instrumental on 'Be m'enueia', arr. Kammen |

ShK, vielle · TR, percussion

2. Be m'enueia, so auzes dire? [7:40]

“I find annoying, do you hear me?” |

TR, voice · ShK, vielle

3. Two motets on 'Era pot' [1:54]

instrumental, arr. Kammen |

ShK, rebec · TR, harp

4. Era pot ma domna saber [7:59]

“Now my lady may know” |

TR, voice · ShK, harp

5. Dansa 'Era pot' [3:09]

instrumental, arr. Kammen |

ShK, vielle · TR, ‘ud

6. Lengua d'argen [2:19]

instrumental on 'Quan tuit', arr. Kammen |

ShK, vielle

7. Quan tuit aquist clam foron fat [7:59]

“When all these complaints have been made” |

cf. Peire VIDAL. Nulhs hom no·s

TR, voice · ShK, vielle · Alison Sabedoria, voice, bell

8. Dansa 'Folhs motz' [1:48]

instrumental on 'Quan tuit', arr. Kammen |

ShK, vielle · TR, percussión

9. Amicx Robert, fe que dey vos [3:34]

“Robert, my friend, I promise you” |

cf. Daude de PRADAS (attr.). Bele m'es la veis |

TR, voice

10. Belha messios [6:13]

instrumental and estampie on 'Amicx Robert', arr. Rayborn |

TR, harp

11. Pos Peire d'Alvernh'a cantat [13:44]

“Since Peire d'Alvernha has sung” |

cf. Guillem ADEMAR. Lai can vei florir

TR, voice, percussion · ShK, vielle

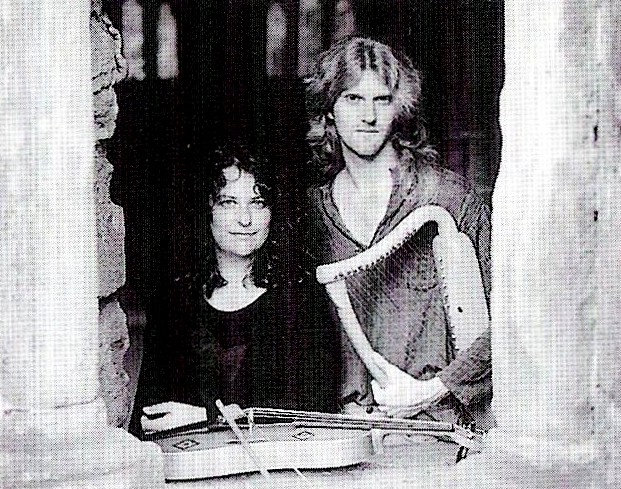

Tim Rayborn · voice, harp, ‘ud, percussion

Shira Kammen · vielle, rebec, harp

with

Alison Sabedoria, voice, bell

TIM RAYBORN

Tim Rayborn, originally from Northern California,

is the founder of Ensemble Florata. He has been devoted to the study and

performance of medieval music and the traditional music of the Middle

East for nearly a decade. He has performed throughout Britain and

Europe, including concerts at both the York and Beverley Early Music

Festivals, and the Jersey International Festival, as well as with

traditional musicians in Marrakesh and Istanbul.

SHIRA KAMMEN

Shira

Kammen is based in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she received her

music degree from U.C. Berkeley, and was for many years a member of both

Ensemble Alcatraz and Ensemble Project Ars Nova. She studied vielle and

medieval music with Margriet Tindemans, and also has worked with the

Boston Camerata, Sequentia, Hesperion XX and The King's Noyse. She has

performed, recorded and taught medieval and traditional music

extensively in the USA, Europe and North Africa.

Instruments

Vielle — Fabrizio Reginato, Fonte Alto, Italy, 1984

Vielle — Karl Dennis, Warren, Rhode Island, USA, 1993

Rebec — John Fleagle, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 1985

Harp — 'Blondel', Tim Hobrough, Strathpeffer, Scotland, 1994

‘Ud — Samir Hamida, Cairo, Egypt

Drum — traditional wooden frame drum

Musical arrangements by Shira Kammen and Tim Rayborn

Contrafacts by Tim Rayborn:

· Quan tuit aquist — adapted by Rayborn from Nulhs horn no·s by Peire Vidal

· Amicx Robert — contrafacted from Bele m'es la veis, ascribed to Daude de Pradas

· Pos Peire d'Alvernh'a — contrafected from Lai can vey florir by Guillem Ademar

Produced by Tim Raybom, Shim Kammen and Colin Potter

Recorded by Colin Potter, IC Studios, 19-21 August, 1997

Translations

of texts by Dr Michael Routledge, Royal Holloway University, London,

and grateful acknowledgments for his assistance and input

Thanks

to Sarah Zandona for her help and initial working translations of the texts

and special thanks to Alison Sabedoria for her invaluable vocal

coaching and contributions

Original recording concept by Shira Kammen

℗ & © 1998

The

Monk of Montaudon stands as a singularly curious and often amusing

figure in the history of troubadour poetry and song. His true name is

unknown, but he flourished in the late twelfth century, and apparently

came from a noble family in the Auvergne region. He suffered the fate

which often befell the younger male children of such families, being

offered to a monastery, in this case the Abbey of Orlac. At some point,

he became Prior of Montaudon, thus acquiring the title by which we now

know him.

However, this man was no ordinary monk, and despite his

enforced devotion to the monastic vocation (or perhaps because of it)

he showed a remarkable talent for vernacular poetry and music, writing

verses in a number of the standard poetic forms employed by the

troubadours of the time. The language was Occitan, a Romance language

resembling Catalan. It was widely-spoken in medieval southern France,

and used to exquisite literary effect by the troubadours.

The

Monk's work attracted the attentions and patronage of the nobility. He

was regularly invited to leave behind the cloister and participate in

their many feasts and tournaments, performing his works and engaging in

the popular poetic and musical contests of the time. The fact that he

dutifully donated the rewards won from these events to the monastery

treasury was no doubt a major factor in his being allowed to continue

this connection with the secular world.

Indeed, at the Court of

Puy Sainte Marie, famous for its troubadour contests, he was made master

of revels. This honour entitled him to open the annual feast with a

ceremony in which he held on his arm a sparrow-hawk, which would then be

accepted by the baron who had chosen to sponsor the event, a sometimes

ruinous expense. The Monk continued such secular connections throughout

his life. He is known to have been active in Spain as well, being

affiliated with the monastery of Villafranca. King Alfonso of Aragón was

among his patrons.

His work differs in some respects from that

of his contemporaries, no doubt due in part to the very different life

which he lived. Many of his poems have a keen wit and biting sarcasm,

quite humorous, even vulgar, but verging at times on the cruel. It is as

if he is holding up the entire genre to ridicule, whilst still making

fine use of the poetic forms.

Chief among these is the Enueg, or

'annoyance' song, wherein the poet describes, in a humorous, random and

seemingly nonsensical manner, various things which he finds irritating.

We include two examples here [tracks 2, 9]. It is very possible that

these works provide tantalising glimpses into the Monk's own life, in

which case, he was far from pious!

The longest piece on this recording is a Sirventes, Pos Peire.

Here the Monk's invective is in fine form, as he takes an impish glee

in mercilessly insulting and demeaning his musical contemporaries,

before finally turning his venom on himself.

Quan tuit recounts a curious debate in heaven between religious icons and ladies over the right to use facial paint. Era pot

is a more typical courtly love lyric, and is the only non-satirical

piece on this recording. It was probably composed according to courtly

conventions rather than expressing any true feelings. However, given

that the Monk's entrance into the monastic life was probably unwilling,

ant that he had continual contact with various courts throughout his

life, we will probably never be certain of his amorous intentions.

Only two of the Monk's pieces have survived with music, Be m'enueia and Era pot. Be m'eneuia, shares its melody with a piece by Bertan de Born, Rassa, tan derts. The question, therefore, as to which of these two wrote music the music is open to speculation.

In

order that these wonderful poems can live again musically for the

modern listener, we have created contrafacts, that is, taken existing

melodies from the Monk's contemporaries and set his words to their

music. Thin was it wide-spread practice throughout the Middle Ages, with

new poems often being set by their authors to popular songs of the day.

Instrumental

music abounded in the Middle Ages, commonly being created based on

vocal models, and we have provided examples here of this practice. Such

pieces would have been played to enhance the performance of troubadour

songs, and could have involved a number of different instruments. We

have provided titles for them taken from the Monk's poetry.

Concerning

performance practice, it appears that often troubadour poems were sung

unaccompanied or with a single instrument, the favourite of which was

the vielle (the medieval fiddle). The harp also seems likely for such

music, though the evidence for the use of instruments with the various

types of troubadour songs is rather confusing and inconclusive. We

believe that medieval musical practices were varied enough in different

regions and times to allow for both types of performance, and we reflect

this on the recording. The texts are interpreted theatrically,

reflecting their amusing and even ridiculous content. These songs were

obviously meant for the listeners' amusement and so invite a variety of

vocal colours and effects.

It is hoped that the music of this

unusual man will entertain the modem listener, with both the cleverness

of its literary content and the richness of its melodies. The Monk of

Montaudon lived in two very different worlds, with one foot in each. His

unique position allowed him to offer his own critique of his life as a

troubadour, and at the same time not scandalise his religious vocation.

His amusing bits of monastic nose-thumbing make a refreshing change

indeed!

Tim Rayborn, 1998