Discant CD-E 1006

1998

Discant CD-E 1006

1998

REPRESENTACIONES DRAMÁTICAS EN LA CATALUÑA MEDIEVAL

Los bellos monumentos del medioevo que salpican la geografía

catalana nos retrotraen a unos tiempos donde una parte importante del

arte expresaba un pensar y un sentir religiosos a través de la

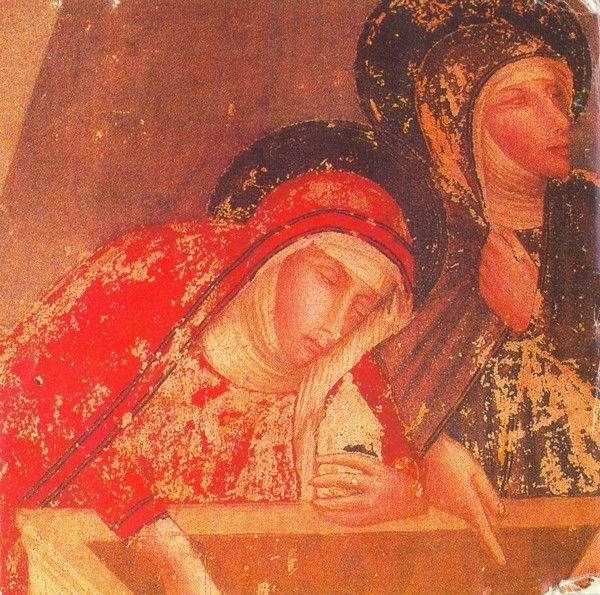

imagen, el sonido o la palabra. En las iglesias las imágenes de

relieves, frescos y capiteles hablaban del cielo y del infierno, del

bien y del mal, de los protagonistas de la historia sagrada y de sus

hechos, los mismos a quienes las músicas cantaban alabanzas

dentro de un marco litúrgico construido al filo argumental de

dos aconteceres: el nacimiento y la Resurrección de Cristo, tras

su muerte. Navidad y Semana Santa constituían, por así

decir, los ejes en torno a los cuales giraba y sigue girando la

liturgia cristiana y en función de ello las manifestaciones

artísticas sacras. Entre ellas la música ocupa un lugar

preferente por ser la más ligada a la liturgia.

Tuvo que pasar mucho tiempo, nada menos que diez siglos, para que el

músico, de la mano del poeta, pudiese escribir cantos y

melodías sacras al margen de las estrictamente

litúrgicas; y ello por el celo de la Iglesia en tratar de

mantener su unidad. Con las liturgias unificadas, en el siglo

XI o poco antes empezaron a florecer en Europa las primeras

manifestaciones poético-musicales sacras, que andando el tiempo

recibirían el nombre genérico de tropos. Tropos los hubo

para todas y cada una de las festividades del año, pero el

número de los dedicados a las de Navidad y Pascua superó

a cualquier otro. Entre los tropos de Pascua adquirió especial

relevancia uno del Introito de la Misa, Quem quaeritis in sepulchro,

que no tardó en dar origen a la primera representación de

la que se tiene noticias en el medioevo: el drama de la Visitatio,

cuyo argumento rememora la visita de las tres Marías al sepulcro

de Cristo. A imitación suya nacieron otros, iniciándose

así en occidente la historia del drama lírico.

La versión más antigua conservada en tierras catalanas

del drama de las tres Marías es del siglo XII y procede de la

catedral de Vic (Ms 105 fols. 58v-60r). Encabezado por la

rúbrica Verses pascales de.III.Mariis, su primera

sección da comienzo con una estrofa de cuatro versos que cantan

las Marías, que expresan su deseo de comprar mirra para ungir el

cuerpo de Cristo. El fragmento se articula mediante cuatro frases

musicales de las cuales la segunda y la cuarta son casi

idénticas.

Siguen cuatro estrofas con refrán de cuatro versos cada una

(II-V), que corresponden al Omnipotens Pater altissime, bien

conocido durante la Edad Media. Todas las estrofas repiten la misma

música, en la que se suceden dos frases idénticas, una

tercera cuyo final coincide con el de las anteriores y el

refrán. La primera estrofa la canta un Angel y las otras tres

las Marías. Sumidas en su dolor, éstas hallan por fin al

mercader de ungüentos, el cual alaba su mercancía a lo

largo de tres estrofas sin refrán (VI-VIII), cuya música

deriva de la del fragmento anterior. Le responde una de las

Marías (estr. IX), repitiendo la melodía del Omnipotens.

Ni de esta composición ni de la que hace de introducción

se conocen más versiones.

A continuación María Magdalena se dirige a sus

compañeras en un lamento que se extiende a lo largo de nueve

estrofas (X-XVIII), de las cuales solo se copia la música de la

primera y el principio de la segunda; no obstante es evidente que todas

las estrofas repiten la misma música, a pesar de que su

número de versos sea dispar (las cinco primeras constan de siete

versos, las tres siguientes de cuatro y la última de seis). La

música que corresponde a la primera estrofa se divide en siete

frases —una por cada verso-. idénticas dos a dos salvo la

quinta que es diferente. Con el fin de facilitar la aplicación

de la música, el copista tuvo la precaución de

señalar en las estrofas XI-XIV el verso al que corresponde la

frase musical independiente mediante una letra minúscula. En las

estrofas XV-XVIII, con un número de versos par, la frase no se

utiliza.

El lamento de María Magdalena enlaza con la segunda

sección de la Visitatio. Consiste en el texto y

música del tropo Ubi est, tal cual figura en un tropario

de Vic del siglo XIII (Ms 106 fol. 48v), solo que se suprime la

última frase que servía de enlace con el introito de la

Misa de Pascua; en lugar suyo se canta el Te Deum laudumus,

final del tercer nocturno de Maitines de los domingos y fiestas

solemnes, que por tanto señala su posicion litúrgica.

A continuación de los Verses pascales de.III.Mariis el

viejo tropario de Vic copia lo que titula Versus de pelegrino

(fols. 60r-62r), una representación que incluye la famosa escena

de la aparición de Cristo a María Magdalena propia de las

Visitatio sepulchri más evolucionadas, junto con la

escena del Mercader; es en el tropario usonense donde una y otra

aparecen por primera vez en Europa. A pesar de que su argumento enlaza

con el de las Marías, el Peregrinus se representaba en

Vic durante las vísperas del Lunes de Pascua. El tropario da el

texto completo de la representación pero en cambio solo copia la

música de sus doce versos primeros, ocho de los cuales

corresponden al Rex in accubitum, con el que da comienzo la

obra. El fragmento, que canta Marla Magdalena, es un unicum; se

estructura en ocho frases idénticas dos a dos, excepto la

tercera y la séptima. Tras la sexta frase interviene

súbitamente el Ángel cantando el verso "Muller, quid

ploras? Quern queris?". que es el que da inicio a la escena de la

Magdalena en las demás representaciones que la incluyen. Tras la

respuesta de María es Cristo, en apariencia de un Hortelano,

quien le formula la misma pregunta que el Ángel. El resto de la

escena, con el diálogo de la María y el Hortelano, sigue

el patrón común.

La escena siguiente corresponde a la estrofas dialogadas de la

secuencia Victimae paschali laudes, "Dic nobis, Maria" etc., a

cargo de María Magdalena y los discípulos de Cristo,

interrumpida de nuevo por el Ángel que entona una frase del

drama de las tres Martas, "Non est hic" etc., A continuación y

para concluir se introduce la escena que constituye el núcleo

propiamente dicho de las representaciones de Peregrinus, con el

diálogo de Cristo resucitado y Cleofás, interrumpida tras

la intervención posterior de dos discípulos. Juzgado en

su conjunto el resultado es una obra un tanto ecléctica no

exenta de originalidad, que incorpora materiales de dos

representaciones distintas: Visitatio fundida con la secuencia

dramatizada del Victimae paschali laudes, de la que por cierto

el Cancionero Musical de la Colombina da una espléndida

versión polifónica (fol. 83r), y el Peregrinus.

La versión que el tropario de Vic transmite de estas obras queda

lejos del modelo artístico que suponen las del famoso libro de

representaciones de Fleury, aunque son un importante testimonio sobre

la actividad músico-dramática de un centro religioso con

capacidad pare asimilar nuevos productos artísticos y a su vez

reelaborarlos.

A pesar de la popularidad de que gozaron ambas representaciones

dramáticas en Cataluña, juntas o por separado, su fama no

fue comparable a la del Canto de la Sibila, último de los

fragmentos del drama de la Procesión de los Profetas,

representado total o parcialmente durante los maitines de la Navidad.

Frente a los Profetas del antiguo y del nuevo Testamento, de los

personajes de Cristo y las tres Marías, la Sibila, profetisa de

la antigua Grecia a quien San Agustín le atribuye unos versos

que vaticinan el Juicio Final, tenía el atractivo de ser un

personaje pagano. De la Seu d'Urgell á Valencia, de Huesca a

Palma de Mallorca, la presencia de la Sibila se convirtió en

imprescindible en la mayoría de las iglesias. Su canto,

mantenido con notable estabilidad durante siglos, evoca como

ningún otro los miedos del hombre medieval ante el castigo

divino, al que el Renacimiento le pierde un cierto respeto convirtiendo

a la Sibila en un elemento mas folklórico que espiritual, que el

Concilio de Trento se apresuró a eliminar.

Trento también prohibió muchísimos de los tropos

que enriquecían y adornaban la liturgia, aunque no pudo hacerlo

con su variante más sofisticada, la polifonía, nacida

como un adorno en el espacio en lugar de en el tiempo. Entre los bellos

ejemplos de polifonía primitiva que se conservan en

Cataluña figuran los condueles, cánones y motetes de

sendos códices procedentes de los monasterios de Ripoll (Archivo

de la Corona de Aragón, Ripoll 139), Montserrat (Llibre Vermell)

y Vallbona de les Monges (Cód. 1/add.) y de la catedral de

Tortosa. partícipes de una tradición nacida en los

aledaños de la catedral de Notre Dame de París, de amplia

raigambre europea. Una tradición que a fines del medioevo

desembocó en el Ars Nova, estilo del que en Cataluña y

por extensión en el antiguo reino de Aragón se conservan

múltiples y variados ejemplos de polifonía sacra, que van

del sencillo Credo a 2 voces (Palma de Mallorca, Museo Diocesano) al

Kyrie a 3 voces, todas con el texto tropado (Catedral de Girona. Ms

33/II).

Maricarmen Gómez Muntané

LITURGICAL DRAMA IN MEDIEVAL CATALONIA

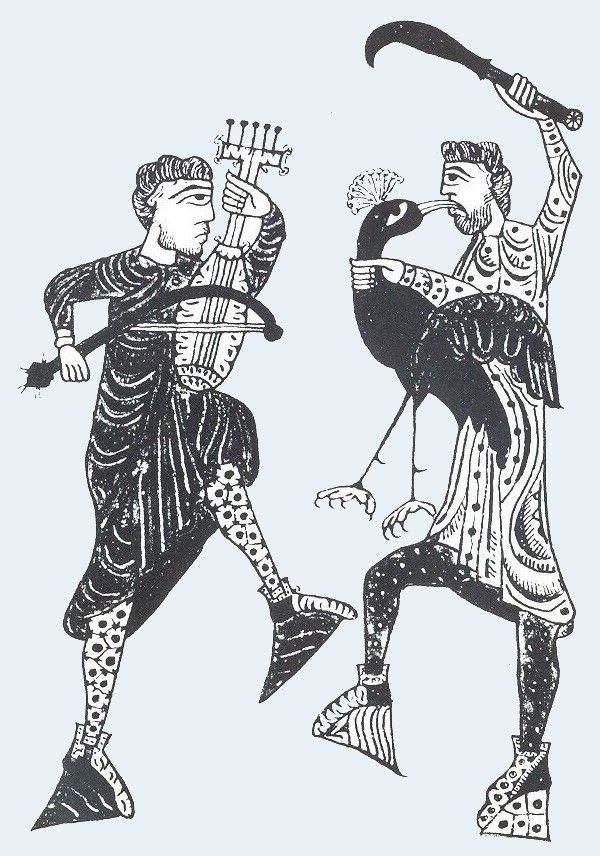

The beautiful medieval monuments which dot the Catalan countryside take

us back to a time when many artistic endeavours —art itself

expressed a thought, a deep religious faith through images, sounds and

words—. In churches, relief figures, frescos and sculptures spoke

of heaven and hell, good and evil, recounting the lives of men and

women in the Bible. Christians later praised them in song and drama

within the Liturgy. The Birth and Resurrection of Christ were the main

events depicted. Christmas and Holy Week were and still are the central

focal points of Christian worship and they received the bulk of the

artist's and the musician's attention, music being such an important

part of the Liturgy. Much time went by —nearly ten

centuries— before the musician and the poet could join forces and

create songs and sacred melodies outside a strictly liturgical setting.

Why? The Church was very eager to maintain its unity. Liturgical

practices were finally unified around the XIth c. Soon afterwards, the

first paraliturgical chants and texts began to appear. They were known

as Tropes. Trope composition mushroomed and soon were found in every

celebration on the Roman Calender, those for Christmas and Easter were

particularly prolific. Of these. Quem quaeritis in sepulchro,

the Easter Day Introit Trope, was most popular and inspired the first

extant liturgical drama. The plot of the Visitatio tells the

story of the Three Women who visited Christ's Tomb. With this as a

starting point, many others followed and, thus, Western Theatrical

Tradition was born.

The oldest extant version of the Visitatio or the Three

Marys in Catalonia comes from the Cathedral in Vic (MS 105 ff.

58v-60r). The rubrics at the beginning read: Verses pascales ele

.III. Mariis. The first section starts with a strophe containing

four verses which the three Women sing about how they've got to buy

some myrrh so they can anoint Christ's body. This first part has four

musical phrases, the second and the fourth being almost identical.

After that, come 4 strophes with four verses each plus a refrain

(II-IV) which is set to the Omnipotens Pater altissime, so

well-known in the Middle Ages. All the strophes have the same music in

which the first two phrases are identical, a third one whose end

coincides with the end of the others plus the refrain. The Angel and

the Three Marys, overcome by their grief, sing the first strophe. They

finally run into the Merchant who sell them the Ointments, but then

begins to praise his merchandise for the next 3 strophes (VI-VIII, no

refrain). This is set to the same music we've already heard. One of the

Women answers him (strophe IX), repeating the Omnipotens. This

composition along with its Introduction are unique M that no other

versions have come to light so far.

Mary Magdalene sings a lament to her friends lasting 9 strophes

(X-XVIII). Music is only extant for the first strophe and the beginning

of the second, but it is clear the music is the same even though the

number of verses varies (the first 5 have 7 verses, the following 3

have 4 verses and the last one 6). Musically, the first strophe

contains 7 phrases, one for each verse. Each pair of verses is

identical, except for the 5th which is different from the others. In

strophes XV-XVIII, with even numbered verses, this phrase is left out.

Mary Magdalene's Lament leads straight into the second section of the Visitatio.

The music and text are from the Trope, Ubi est, which appears

in a XIIIth c. Troper from Vic (MS 106 f. 48v). The last phrase of this

Trope, which would have led into the Introit Chant for the Easter Mass

is omitted. Instead, the Te Deum laudamus is sung, a chant

normally used at the end of Matins on Sundays and Feast Days.

Following the Verses pascales de .III. Mariis in the Old Vic

Troper, we find a copy of the Versus de pelegrino (ff.

60r-62r), a play including Christ's famous appearance to Mary Magdalene

normally included in later versions of the Visitatio sepulchri,

and alongside the Oil Merchant's scene. These two scenes appear in this

source for the very first time in Europe. Although the text leads

straight into the scene of the Three Marys, it was performed in Vic at

Vespres on Easter Monday. The entire text is present in this source,

but only the first twelve verses of its music, eight of them being the Rex

in accubitum, which begin the play. Mary Magdalene's music is a unicum;

it consists of 8 identical phrases -in pairs- with the exception of the

3rd and the 7th. After the first phrase, the Angel suddenly enter

singing: "Mulier, quid ploras? Quem queris?" which is where Mary

Magdalene's scene normally occurs in other plays. Mary replies, then

Christ, in Gardener's clothing, asks the same question the Angel just

asked. The rest of the scene, with its dialogue between Mary and the

Gardener, follows the standard pattern. The following scene uses the

dialogue strophes in the Easter sequence Victimae paschali laudes,

"Dic nobis Maria", etc. between Mary Magdalene and the Disciples. This

is interrupted again by the Angel who sings a phrase from the Three

Marys play: "Noc est hic", etc. Bringing this to a close is the

dialogue between the Risen Christ and Cleophas, the heart of the Peregrinus.

The dialogue breaks off after the two Disciples sing their part. As a

whole, the play is a bit eclectic, but still original, blending

together material from two different works, the Visitatio and

the sequence, Victimae paschali. The Cancionero Musical de la

Colombina, by the way, has a wonderful polyphonic setting of this

sequence (f. 83r), and the Peregrinus. The version in the Vic

Troper is not on a par with the works preserved at Fleury, but it does

illustrate how a religious center of musical activity was able to

assimilate new artistic ideas and re-work them effectively.

In spite of the popularity of these two works in Catalonia, both

separately or together, they were nothing in comparison of the Cant

de la Sibil·la, the last part of another dramatic work, the

Procession of the Prophets, performed as a whole or in part during

Christmas Matins. While standing in front of the Old and New Testament

Prophets, Christ and the Three Marys. the Sibyl —a pagan

prophetess in Ancient Greece— sings an apocalyptic text about the

Last Judgement which St. Augustine attributed to her. From Seu d'Urgell

to Valencia, from Huesca to Palma de Mallorca, her prophecy became an

essential part of many churches. This Song was part and parcel of the

Liturgy for centuries, evoking, as it does, the Medieval fear of divine

punishment. By the Renaissance, people had lost their respect for the

Sibyl; she was little more than a folkloric figure rather than

spiritual. The Council of Trent only hastened her demise and eliminated

her Song.

Trent also suppressed many tropes which had enriched liturgical

celebrations for so long, but it couldn't eliminate is most

sophisticated variant: vocal polyphony, conceived as an ornament in

space rather than in time. Beautiful examples of early Catalan

polyphony —conductus, canons, motets from several codices—

can be found in monasteries such as Ripoll (Arxiu de la Corona

d'Aragó, Ripoll 139), Montserrat (Llibre Vermell) and Vallbona

de les Monges and the Cathedral Church in Tortosa. Theses monasteries

all shared in a common tradition, born in and around Notre Dame in

Paris with deep roots throughout Europe. This tradition evolved into

the Ars Nova at the end of the Middle Ages. In Catalonia and Aragon

there are numerous examples of this New Musical Art in sacred

polyphonic works which vary anywhere from a simple 2 part Credo (Palma

de Mallorca, Diocesan Museum) to a 3 part Kyrie, all of them with

[troped texts (Girona Cathedral, MS 33/11).

Maricarmen Gómez Muntané

Translation: Neil Cowley