Discos Oblicuos DO 0001

2000

Discos Oblicuos DO 0001

2000

These CDs are

packaged in a CD-sized hardbound book of 91 pages. Pierre-F. Roberge

notes that, excluding Cantiga de Maio & Cantiga de escarnio, two

Cantigas (300 & 367) are recorded here for the first time. The

former two un-numbered items are texts by Alfonso which survive in other

sources without music. The first has been set to music by the present

ensemble, using music of a "May song" from a Marian collection. The

second is poetry without music.

The notes for the present program

emphasize the negative events of Alfonso's reign, and especially select

songs in which he speaks about himself and makes negative or derogatory

comments about other people. This revolves mostly around the

unhappiness late in his life. — medieval.org

CD 1

1. Fanfarria alfonsina [1:47]

CSM 195

2. Don Affonso de Castela [1:34]

Presentación —

Rafael Taibo

3. Des oge mais quer' eu trobar [6:37]

CSM 1 —

Emilio Gómez

4. Rosa das rosas e Fror das frores [5:19]

CSM 10 —

Miguel Bernal

5. Quen na Virgen grorios a [6:21]

CSM 256 —

Pablo Heras

6. Miragres muitos pelos reis faz [10:15]

CSM 122 —

María Villa

7. Quen entender quiser [7:31]

CSM 130 —

Pablo Heras

8. Eno pouco e no muito [7:54]

CSM 354 —

Miguel Bernal

9. Santa Maria loei [6:29]

CSM 200 —

Emilio Gómez

10. Muito deveria [6:50]

CSM 300 —

Pablo Heras

CD 2

1. O que da guerra levou cavaleiros [4:57]

Cantiga de Maio ·

CSM 406 —

Miguel Bernal, Pablo Heras

2. Como gradecer ben-feito [17:45]

CSM 235 —

Emilio Gómez

3. Muito faz grand' erro e en torto jaz [8:55]

CSM 209 —

Pablo Heras

4. Non me posso pagar tanto [2:38]

Cantiga de escarnio —

Rafael Taibo

5. Ben parte Santa Maria [9:01]

CSM 348 —

Miguel Bernal

6. Grandes miragres faz Santa Maria [8:19]

CSM 367 —

Emilio Gómez

7. Macar poucos cantares acabei e con son [6:39]

CSM 401 —

Pablo Heras

Alfonsus Rex Sapiens: la sol do re fa mi re

La

fanfarria sirve de frontispicio a los versos sin música que en los

códices de las cantigas presentan al autor. Contienen algunas

exageraciones o inexactitudes (como la conquista del Algarve y el título

de Rey de Romanos) que en sí mismas son representativas de la

personalidad de Alfonso y del momento en que comenzó la colección. En la

primera redacción los últimos versos decían fez cen cantares, pero tras la ampliación se cambiaron por fezo cantares. El término razon,

que aparece en el penúltimo de estos versos, es uno de los conceptos

más complejos en la obra alfonsí. Aquí podría equivaler a "argumento" o,

mejor, "contenido métrico—musical", pero en la cantiga 300 se

encontrarán otras acepciones. Pepe Rey

A SONG BOOK OF ILLUSIONS AND DISENCHANTMENTS

Alfonsus Rex Sapiens = la sol do re fa mi re.

The

fanfare serves as a façade of the verses without music which in the

manuscripts of the songs presents the author. They contain some

exaggerations and errors (like the conquest of the Algarve and the title

of King of the Romans), which in themselves are representative of the

personality of Alphonse and of the time the collection was begun. In the

first draft of the last lines it said he made a hundred songs, but after the enlargement it was changed to he made songs. The term razon (reason),

which appears in the last but one of these lines, is one of the most

complicated concepts in the Alphonsine work. Here it could be equivalent

to "plot" or better still "metrical—musical content", but in song 300

other meanings will be found. Pepe Rey

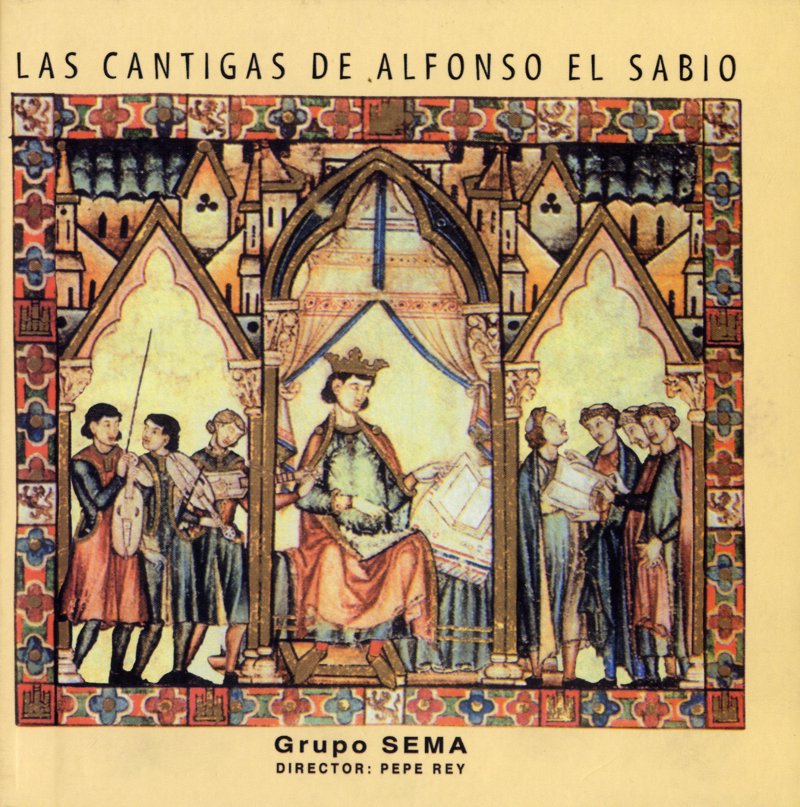

Grupo SEMA

CANTORES SOLISTAS:

María Villa (cantiga 122)

Miguel Bernal (cantigas 10, 354, Maio y 348)

Pablo Heras (cantigas 256, 130, 300, Maio, 209 y 401)

Emilio Gómez (cantigas 1, 200, 235 y 367)

CORO: Ana Manuela Rey, María Villa, Miguel Bernal, Ángel Botia,

Carlos García, Emilio Gómez, Pablo Heras y Pepe Rey.

INSTRUMENTISTAS:

Nuria Llopis, arpa

Itziar Atucha, vihuela de arco

Marcial Moreiras, vihuela de arco

Francisco Javier García, cítola y guitarra

Dimitri Psonis, salterio, laúd, tambor y pandereta

Pedro Estevan, darbuka, tambor, pandero y pandereta

Juan Dionisio Martín, flautas

Francisco Rubio, corneta

Con la colaboración especial de Rafael Taibo, recitador

Pepe Rey, transcripción y dirección

Grabado en la Capilla del Cristo de los Dolores de la Venerable Orden Tercera de San Francisco (Madrid)

del 28 de agosto al 1 de septiembre de 1999.

Registro de sonido: José Luis Crespo e Isidro Matamoros

Editado y masterizado en Mac Master

Edición digital: Pedro García

Masterización en plataforma Sonic Solutions Apogee AD 8.000: Carlos Villa

Texto en castellano: Pepe Rey

Traducción: Ann Farrow

Coordinación y producción : Juan Dionisio y María Villa

Diseño y maquetación: Santiago Villa (Departamento Infografía Mac Master)

(Agradecemos la colaboración de Teresa Rodríguez)

Una producción Discos Oblicuos para Mac Master, S.A.

UN CANCIONERO DE ILUSIONES Y DESENCANTOS

Alfonso

X el Sabio (1222—1284) tenía aproximadamente cuarenta y cinco años y

llevaba reinando quince cuando concibió la idea de componer una

colección de cien cantares a la Virgen. Se encontraba en un momento

esplendoroso, en el que en su mente bullían proyectos tan importantes

como ser elegido Emperador o conquistar el Norte de África, además de

tareas legislativas o científicas de gran envergadura. Su corte era

visitada por embajadores, princesas, sabios y artistas de las más

diversas procedencias. El talante optimista de Alfonso le inspiró el

mensaje fundamental de la colección mariana: todos los problemas tienen

solución, incluso a veces la muerte, para quien confía en Santa María.

Pero si la alabanza a la Virgen y la difusión de la devoción mariana

fueron los motivos iniciales para emprender un esfuerzo tan

considerable, seguramente no fueron los únicos. Resulta evidente, por

ejemplo, el afán de publicidad personal, no solo porque el autor ocupa

una posición central en la obra, sino porque en algunas historias

Alfonso es protagonista y en otras existe una estrecha relación entre él

y lo narrado. Hay también una publicidad interna de la obra: algunas

cantigas cuentan cómo Santa María premia a quienes cantan en su honor.

De este modo Alfonso animaba a los juglares a difundir este repertorio.

Pero también se perciben razones negativas, algunas tan sorprendentes

como la misoginia o los problemas con el obispado de Compostela, que

provocan que las mujeres y Santiago aparezcan bastante nninusvalorados

en la colección.

Cuando ésta alcanzaba ya el número de cien

cantigas, Alfonso decidió ampliarla hasta las doscientas y, cuando llegó

a este número, decidió seguir hasta las cuatrocientas. Sus proyectos

siempre pecaron de megalomanía y muchos de ellos se habían frustrado

porque otros hombres —el Papa, los nobles, las Cortes, etc— se negaban a

colaborar, según la vision interesada del propio Alfonso. Para este

proyecto apenas necesitaba más ayuda que la de sus músicos, copistas y

miniaturistas, por lo que se sintió con posibilidades de acabarlo. Pero,

a la vez que la colección de cantigas avanzaba, el resto de los asuntos

comenzó a ir de mal en peor y en primer lugar la salud, a raíz de una

coz en la cara que recibió en Burgos en 1268 y que acabaría degenerando

en un cáncer del maxilar superior. Particularmente nefasto fue el año

1275, en el que se vio obligado a abandonar definitivamente su

aspiración al Imperio tras la entrevista con el Papa Gregorio X en

Beaucaire, entre Avignon y Arlés. De allí, con la salud seriamente

dañada, tuvo que volver a toda prisa a Castilla debido a la muerte del

heredero, Fernando de la Cerda, la invasion de los benimerines y las

intrigas de algunos nobles junto a miembros de su familia. A partir de

este momento sus reacciones fueron cada vez más agrias y despiadadas,

los episodios de enfermedad más graves y frecuentes, y los problemas con

el entorno familiar más insolubles. Con razón se ha afirmado que su

vejez fue la más triste que nunca tuvo un rey en Castilla.

Toda la compleja trayectoria final de su vida, resumida aquí en unos pocos datos, quedó reflejada en las Cantigas de Santa María,

compuestas durante este periodo. Para esta antología hemos seleccionado

las que mejor traslucen la personalidad, los pensamientos y las

intenciones del autor. Están ordenadas según un criterio biográfico que

pretende combinar cronología y psicología. Cada una se presenta con el

texto completo (excepto las cantigas 235, 367 y 401, debido a su extrema

longitud), a cuya estructura fija de estribillo—estrofa hemos añadido

un preludio instrumental improvisado. En la cantiga 1 y en la de Maio, hemos intercalado además breves interludios.

Siguiendo

las recomendaciones del propio Rey Sabio, hemos procurado huir de la

fantasía —que para él era una especie de peligrosa enfermedad—, aunque a

veces no hemos podido evitar caer en ella, como también le solía

ocurrir a él con frecuencia. Por eso comenzamos con una fanfarria de

carácter heráldico sobre un motivo de la cantiga 195 —que cuenta la

historia de un caballero que murió en un torneo— combinado con los temas

musicales que se derivan del nombre y los títulos del personaje. Quizá

no sea casual, sino más bien una coincidencia poética, que todas las

melodías resultantes se muevan en el modo de Re:

Alfonsus Decimus Rex Sapiens: la sol do re mi do re fa mi re

Alfonsus Legionis et Castelle: la sol do re mi sol mi re fa re re

No es casual que la cantiga 1 glose los siete gozos de la Virgen,

puesto que, según dejó escrito el propio Alfonso en las Partidas, los cantares non fueron fechos sinon por alegría. El trovador comienza su tarea desde este sentimiento fundamental de alegría y lo hace con una especie de juramento: Desde hoy sólo trovaré por la Señora...

Sin embargo, de unas intenciones tan elevadas resulta en los últimos

versos de la cantiga 10 una consecuencia inesperada: ...mando al diablo a los otros amores.

No sabemos qué pensaría doña Violante —hija de Jaime I el Conquistador y

esposa que nunca se resignó a un papel decorativo— ante tal afirmación.

Seguramente no le hizo mucha gracia y menos aún cuando Alfonso amplió

las comparaciones entre la Virgen y el resto de las mujeres en la

cantiga 130, en la que, incluso, una caricaturesca miniatura retrata el

lamentable estado en que las mujeres dejan a los hombres que se enamoran

de ellas. Es posible que por medio de las galanterías "a lo divino"

Alfonso intentara cobrarse alguna venganza "a lo humano". En enero de

1278 doña Violante se refugió en Aragón junto a su hermano Pedro III

porque, según un cronista, el Rey no la trataba con el honor que debía.

¿Encontraron eco en las cantigas marianas los problemas matrimoniales de

Alfonso, como lo encontrarían los problemas políticos? Cabe pensar que

sí, aunque el autor intenta continuamente arrojar tinta (de calamar)

sobre sus intenciones personales con un estilo oblicuo e indirecto.

No

ocurre así en la cantiga 256, en la que Alfonso utiliza la primera

persona para narrar hechos ocurridos a su madre en 1226, de los que él

fue testigo y que recuerda, aunque era menynno. Sin embargo, en la cantiga 122, al contar la milagrosa resurrección de su hermana Berenguela en 1240, habla de una infanta, hija de un rey.

Con idéntico estilo utiliza la tercera persona en la cantiga 354 para

comunicar algo tan personal como su gran amor por una comadreja.

Consciente, quizá, de la trivialidad del asunto para cualquier oyente,

el estribillo avisa de que la Virgen ayuda a los suyos eno pouco e no muito, aunque el milagro es calificado como grande.

La cantiga 200 ocupa el lugar central de la colección. Como todas las decenas, se trata de una cantiga de loor de Santa María,

pero en ésta el autor parece mirar más hacia sí mismo que hacia su

dama. Por primera vez hace aquí Alfonso alusión a sus enemigos y al

castigo que la Virgen les ha propinado, añadiendo un amenazador como probaré,

que se hará efectivo en algunas cantigas posteriores. Dos de los

conceptos más complejos del lenguaje alfonsí —muy utilizados, por

ejemplo, en otra de sus obras personales, el Setenario— son el entendimento y la razon.

Jugando con los diversos sentidos del primero de ellos se construye la

cantiga 130, de fondo fuertemente misógino, como he dicho más arriba. La

300 juega con las varias acepciones del segundo, para acabar pidiendo

sarcásticamente a la Virgen que premie como se merecen a los que le

critican. Son síntomas claros de que los fines piadosos que en un

principio movían al Rey Sabio al escribir sus cantigas se iban desviando

hacia objetivos personales, aunque su lenguaje intentara siempre

envolverlos en loores y milagros.

En la Cantiga de Maio se

hace patente la crítica a los nobles rebeldes. Nuestra versión está

elaborada con alguna dosis de fantasía, por lo que conviene aclarar

ciertos detalles. En la colección mariana se copia una cantiga das Mayas, con el estribillo Ben vennas, Mayo

y estrofas de cuatro versos endecasílabos. Por otra parte, en tres

colecciones poéticas galaico—portuguesas aparece sin música una cantiga

de Alfonso X con el estribillo Non ven al maio y estrofas de dos

versos endecasílabos. Teniendo en cuenta las similitudes métricas y

basándonos en la opinión de que tanto la cantiga profana como la

religiosa son contrafacta de una canción tradicional de mayo,

hemos tomado la música de la primera adaptándola al texto de la segunda y

hemos reestructurado todo según modos paralelísticos tradicionales, en

los que dos solistas dialogan y el coro responde con el estribillo. El

contenido fuertemente crítico contra los nobles, por los que el rey

Alfonso se siente traicionado, incluye a esta cantiga dentro de los

géneros de escarnio y maldizer, estilo en el que Alfonso X

puede ser considerado gran maestro. Semejante tono resulta normal en

las cantigas profanas —que nos han llegado sin música y son mucho menos

conocidas— en cuyo lenguaje Alfonso llega más de una vez hasta la

obscenidad y el sacrilegio. Lo sorprendente es que encontremos cosas

parecidas en la colección religiosa. El ejemplo más sorprendente es la

larga cantiga 235, en la que se narran hechos acaecidos entre 1273 y

1278 o, mejor dicho, se presenta la personal e interesada versión de

Alfonso sobre los mismos. El estilo oblicuo adopta en este caso la

narración en tercera persona, aunque multitud de sutiles detalles

descubren la mano que está escribiendo. Sarcasmo se llama a la figura

retórica empleada en el estribillo, cuyo mensaje, "debemos ser

agradecidos", no se dirige a los devotos de Santa María, sino a los

ingratos vasallos del propio Alfonso, que cuando éste volvía enfermo de

su entrevista con el Papa, le saludaban cortésmente, aunque en realidad

intentaban destronarlo. Algunas frases expresadas en medias palabras

contienen acusaciones particularmente graves. En marzo de 1277 ordenó el

arresto y ejecución sin juicio de su hermano Federico (Fadrique) y de

Simón Ruiz de los Cameros. Es posible que ambos estuvieran tramando una

conspiración, pero lo que Alfonso deja deslizar en esta cantiga es una

acusación de homosexualidad: ardeu a carne daqueles que non querían moller,

seguida de amenazas al resto de los conspiradores. Uno de los momentos

más fuertes de esta cantiga lo constituye la frase que remata este

episodio: me importa muy poco el mal que les ocurra, en la que la primera persona se desliza como un revelador lapsus linguae del narrador. También denota un fuerte delirio de megalomanía la seguridad de que en esta vida no habría juez que pudiera juzgarlo.

En resumen, la cantiga 235 nos presenta una cara del Rey Sabio muy

distinta de la confiada alegría de los comienzos. Por estos años son

constantes los empeoramientos de salud con las consiguientes curaciones

milagrosas. Los hechos de la cantiga 209 se sitúan en 1277, poco antes

de las citadas ejecuciones.

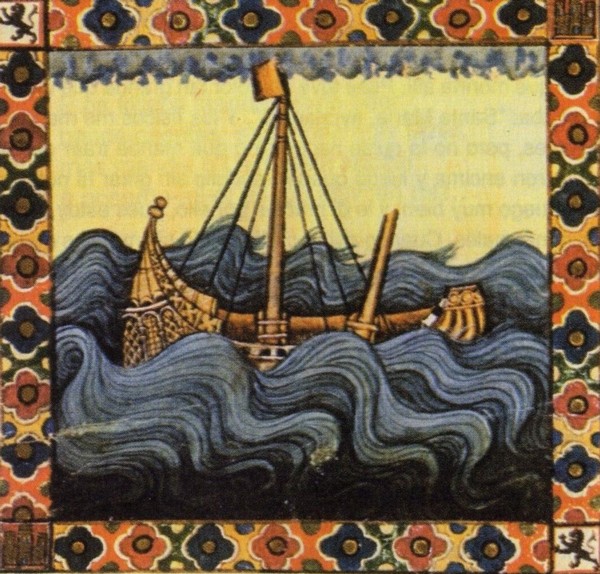

El mejor testimonio del estado de

decaimiento a que llegó el rey Alfonso a causa de sus desavenencias con

la familia y la nobleza es la cantiga Non me posso pagar tanto,

sin duda su mejor poema, que hemos querido incluir en esta antología,

aunque su música, para nuestra desgracia, no se ha conservado. Es tal su

grado de verdad, que un cronista posterior, Pedro de Escavias,

escribió: El rey don Alfonso, estando desesperado y padeciendo asaz

pobreza, mandó fazer una galea negra con intinción de entrar en ella e

irse a nunca jamás tornar. Las cuestiones económicas, ciertamente,

tampoco le iban nada bien, por lo que hubo de recurrir otra vez a Santa

María, tal como cuenta la cantiga 348, aunque los hechos comprobados

históricamente parecen ser algo distintos de la versión cantable. En

1280 ejecutó a don Zag de la Maleha, judío, que había sido el encargado

de sus finanzas durante muchos años, y encarceló a los judíos que

actuaban de recaudadores de impuestos. Con tal operación, sin embargo,

no logró los fines económicos que perseguía, por lo que al año siguiente

arrestó a los representantes de las comunidades judías y les exigió un

fuerte rescate. Esta vez sí consiguió sus objetivos y es a estos tesoros

a los que se refiere en la cantiga, envolviendo la historia en

inspiraciones marianas y omitiendo datos tan sencillos como el lugar

donde estaba el supuesto tesoro. Así se hace del todo evidente el

carácter propagandístico que había adquirido la colección, convertida en

vehículo de expresión de las intenciones y justificaciones reales.

Particularmente claros se hacen estos objetivos en el ciclo de

veintitrés cantigas que tienen por escenario el Puerto de Santa María,

población fundada por Alfonso X como avanzadilla para frenar las

invasiones africanas, para lo que necesitaba que acudieran nuevos

pobladores. Si hiciéramos caso a la publicidad alfonsí, no existiría en

el mundo otro lugar mejor para vivir, porque en él Santa María hacía

milagros continuamente. La peregrinación de Alfonso a la iglesia del

Puerto, narrada en la cantiga 367, y la curación de su más que probable

hidropesía ocurrieron en septiembre de 1281.

La Petiçon

que cierra el conjunto de cuatrocientas cantigas fue escrita en algún

momento bastante anterior; antes, incluso, de la crisis de 1275, porque

en la redacción primitiva la segunda estrofa decía fezesse cen cantares, frase que después se cambió por fezess' ende cantares. Aunque la petición fundamental del rey-poeta es alcanzar el paraíso tras el gran juyzio,

no se olvida Alfonso de otros problemas de la vida cotidiana. Sin

embargo, el poema tiene verdadero carácter final, porque nos presenta a

un Alfonso el Sabio bastante despojado de sus pompas reales —todo lo

contrario que los versos del principio— y cuyo único argumento de

defensa son las cantigas compuestas en loor de Santa María. No sabemos

si ésta concedió a su trovador el preciado galardón. Dante, que visitó

aquellas regiones pocos años después, no lo vio en el Infierno ni en el

Purgatorio y sólo oyó una voz que hablaba de él, aunque en tono algo

peyorativo, al pasar por el sexto cielo. Quizá con el tiempo haya

ascendido algo más cerca de su dama.

Alphonse X the Wise

(1222 — 1284) was approximately forty—five years old and had been

reigning for fifteen years when he conceived the idea of composing a

collection of one hundred songs to the Virgin. He was experiencing an

exceptional moment as his mind was in a hectic state going over such

important projects like being elected Emperor or conquering North

Africa, as well as important legislative and scientific work. His court

was visited by ambassadors, princesses, intellectuals and artists from

very different backgrounds. Alphonse's optimistic frame of mind inspired

the fundamental message of the Marian collection: all problems can be

solved, including occasionally death for whose who confide in Holy Mary.

However, if the praise of the Virgin and the diffusion of Marian

devotion had been the initial motives for undertaking such a

considerable effort, they were not the only ones. The desire for

personal publicity, for example, appears evident because not only does

the author occupy a central position in the work, but he is also the

main character in some stories and there is, moreover, a close

relationship between him and the narrative. There is also an internal

publicity in the work: some songs relate how Holy Mary rewards those who

sing in her honour. In this way Alphonse encouraged the jongleurs to

spread the repertoire. Negative messages can also be detected, some of

which are so surprising like his misogyny, or the problems with the

bishopric of Compostella, which lead to women and St. James appearing

somewhat less valued in the collection.

When the latter reached

the number of one hundred songs, Alphonse decided to increase them to

two hundred and when he reached this number he decided to continue to

four hundred. His projects were always too megalomaniac and many of them

had failed because other men —the Pope, the nobles, Parliament, etc—

refused to collaborate, according to Alphonse's own selfish viewpoint.

For this project, the only help he needed was that of his musicians,

copiers and miniaturists, and he felt, therefore, that he had the

possibility of completing it. However, as the collection of songs

advanced, other factors gradually worsened the issue. In the first place

his health was weakened, due to a kick in the face he received in

Burgos in 1268 and which ended in cancer on his upper jaw. The year 1275

proved particularly fatal, as he was obliged to abandon his great

ambitions regarding the Empire after the meeting with Pope Gregory X in

Beaucaire, between Avignon and Arles. From there, his health seriously

impaired, he had to return in a hurry to Castile, due to the death of

the heir, Fernando de la Cerda, the invasion of the Benimerins and the

intrigues of some nobles together with members of his family. From that

moment, his reactions became more and more callous, the periods of

illness more and more serious and the problems in his family environment

more and more difficult to solve. lt has been affirmed that his old age

was the saddest that any king of Castile ever had.

The whole of the final complicated phase of his life, summarized here in just a few details, was reflected in his Cantigas de Santa María,

composed during that period. We have selected for this anthology the

songs which reveal the personality, the thought and the intentions of

the author. They are ordered according to a biographical criterion,

which tries to combine chronology and psychology. Each one is presented

as a complete text (except songs 235, 367 and 401, due to their great

length), and we have added an improvised instrumental prelude to their

fixed structure of refrain—verse. We have, moreover, inserted brief

interludes in Song 1 and in the Song of May.

Following

the recommendations of the Wise King himself, we have tried to steer

clear of fantasy —which for him was a kind of dangerous illness—,

although at times we were not able to avoid doing this, as was also

frequently the case with him. For this reason, we commence with a

fanfare of an heraldic nature on a motif of song 195 —which relates the

story of a knight who died in a tournament— combined with the musical

themes derived from the name and titles of the character. Perhaps it is

not by chance, but more probably a poetical coincidence, that all the

resulting melodies move in the mode of Re:

Alfonsus Decimus Rex Sapiens = la sol do re mi do re fa mi re

Alfonsus Legionis et Castelle = la sol do re mi sol mi re fa re re.

lt is not by chance that song 1 glosses the seven joys of the Virgin, because, according to what Alphonse himself had written in the Partidas, the songs were only made for happiness. The troubadour begins his task with this fundamental feeling of joy and he does so with a kind of oath: From today I will only sing for my Lady ... However, from such lofty intentions appears an unexpected consequence in the last lines of song 10: ... I will say to hell with other loves.

We do not know what Mistress Violante —daughter of James I the

Conqueror and a wife who never resigned herself to a decorative role—

would think about such a statement. She probably did not consider it

very amusing and even less so when Alphonse extended the comparisons

between the Virgin and the rest of women in song 130, in which a

satirized miniature describes the deplorable state in which women leave

men who fall in love with them. It is possible that Alphonse might be

trying to take revenge in "a human way" through gallantries in "a divine

way". In January of 1278, Mistress Violante withdrew to Aragon with her

brother Peter III because, according to a chronicler, the King did not

treat her with the honour she deserved. Were Alphonse's matrimonial

problems reflected in the Marian songs in the same way as the political

ones? It is possible to think affirmatively, although the author

continuously tries to hide his intentions with an indirect and oblique

style.

This does not occur in song 256, in which Alphonse uses

the first person to narrate the events which happened in 1226 to his

mother, which he witnessed and remembers although he was a child. In song 122, however, when he relates the miraculous resurrection of his sister Berenguela en 1240, he speaks of a princess, daughter of a king.

In identical style he uses the third person in song 354, to communicate

something so personal as his great affection for a weasel. Aware,

perhaps, of the triviality of the matter for any listener, the refrain

informs us that the Virgin helps her followers in the little and the

big, although the miracle is classified as big.

Song 200 occupies a central place in the collection. Like every tenth one, it is a song of praise to Holy Mary,

but in this one the author appears to contemplate more himself than his

lady. Here for the first time Alphonse alludes to his enemies and how

the Virgin has punished them, adding a threatening as I will prove,

which is fulfilled in later songs. Two of the more complicated concepts

of the Alphonsine language —much used in another of his personal works,

the Setenario—, are entendimento (understanding) and razon (reason).

Playing with the different meanings of the former, song 130, of an

intense misogynous character, is composed. Song 300 plays with the

various meanings of the latter concept and ends requesting the Virgin to

reward as they deserve those who criticize him. These are clear

symptoms that the pious aims which initially inspired the Wise King

began to digress in the direction of his personal objectives, even

though his language tries to cover them up with praises and miracles.

In the Song of May

the criticism directed at rebellious nobles becomes evident. Our

version has been elaborated with a dosis of fantasy, for which reason it

is advisable to clarify a few points. In the Marian collection, the May Feast Song is copied with the refrain Ben vennas, Mayo (Welcome, May)

and verses of four hendecasyllabic lines. On the other hand, in three

collections of Galician—Portuguese poetry, a song of Alphonse X appears

without music and with the refrain Non ven al maio (Do not come to the May Feast)

and verses with two hendecasyllabic lines. Taking into account the

metrical similitudes and basing our judgement on the opinion that both

the secular and religious songs are contrafacta of a traditional May

song, we have taken the music of the former and adapted it to the text

of the latter. We have also re-structured the whole according to

traditional parallelistic ways, where two soloists converse and the

choir responds with the refrain. Its highly critical content against the

nobles, by whom Alphonse felt betrayed, places this song within the

genre of mockery and curse, a style in which Alphonse X can be

considered a great master. A tone like this is normal in secular songs

—which have come down to us without music and which are much less known—

the language of which used by Alphonse reaches the level of obscenity

and sacrilege. It is surprising that we find similar things in the

religious collection. The most astonishing example is in the long song

235, in which the events which occurred in 1273 and 1278 are narrated,

or rather his personal and selfish version of them, which Alphonse wrote

with his own interests in mind. The oblique style adopts in this case a

narrative in the third person, although many subtle details discover

the hand behind them. The rhetorical figure of sarcasm is employed in

the refrain, the message of which, "we must be grateful", is not

directed at the devotees of Holy Mary but at Alphonse's own ungrateful

subjects, who, when the King returned ill from his interview with the

Pope, greeted him politely, though they were really trying to overthrow

him. Some phrases with hinting overtones contain very serious

accusations. In March of 1277, he ordered the arrest and execution

without trial of his brother Frederick (Fadrique) and Simón Ruiz de los

Cameros. It is possible that both of them might have been planning a

conspiracy, but what Alphonse allows to slip into this song is an

accusation of homosexuality: the flesh of those who did not want women burned,

followed by threats at the remaining conspirators. One of the most

important moments of this song comes with the phrase which ends this

episode, I care very little about the evil they may encounter, when the use of the first person appears as a revealing lapsus linguae of the narrator. Moreover, the certainty that in this life there could be no judge who would be able to judge him

denotes serious ravings of megalomania. To sum up song 235 shows us a

very different side of the Wise King from the confident joy of the

beginnings. During those years there was a continuous deterioration of

his health with the consequent miracles. The events of song 209 take

place in 1277, shortly before the above mentioned executions.

The

best testimony of the state of decline experienced by King Alphonse,

due to the quarrels with his family and the nobles, is the song Non me posso pagar tanto,

undoubtedly his best poem, and included in this anthology in spite of

the fact that its music unfortunately has not been conserved. The degree

of truth contained therein is such that Pedro Escavias, a later

chronicler, wrote: King Alphonse, feeling very desperate and

suffering great poverty, had a black galleon made with the intention of

boarding her and never returning. His financial affairs were

certainly not going too well, and it therefore became necessary to

appeal to Holy Mary, just as song 348 relates, although a historical

verification of these events proves rather different from the version to

be sung. In 1280 he executed Zag de la Maleha, a Jew who had been in

charge of his financial affairs for many years, and he imprisoned the

Jews who worked as tax collectors. With these measures, however, he did

not attain the financial aims he was pursuing and so the following year

he arrested the representatives of the Jewish communities and demanded a

big ransom. This time he did achieve his objectives and it is to these

treasures that the song refers, wrapping the story up in Marian

inspirations and omitting such simple information like the place where

the said treasure was. The propagandistic character the collection had

acquired thus becomes quite evident as it had been converted into the

vehicle of expression of the royal opinions and justifications. These

objectives are particularly clear in the cycle of twenty—three songs

which have as a setting El Puerto de Santa María (the Port of Holy

Mary), a town founded by Alphonse X as an outpost to control the African

invasions and for which he needed new settlers. If we took any notice

of the Alphonsine publicity, there would be no better place in the world

to live because Holy Mary continually performed miracles there. The

pilgrimage of Alphonse to the church of the Port, narrated in song 367,

and the cure of his more than probable dropsy, occurred in September of

1281.

The Petiçon which ends the group of four hundred

songs was written quite some time before, prior even to the crisis of

1275, because in the primitive draft the second verse said he made one hundred songs, which phrase was changed to he made songs about it.

Although the fundamental request of the poet-king is to reach paradise

after the great judgement, Alphonse does not forget other problems of

daily life. However, the poem has real final character because it shows

us Alphonse the Wise stripped of his royal pomp —quite the contrary to

the initial verses— and whose sole argument of defence are the songs

composed in praise of Holy Mary. We do not know if she gave her

troubadour the greatly valued reward. Dante, who visited those regions a

few years afterwards, did not see him either in Hell or in Purgatory

but heard a voice which spoke about him in a somewhat negative tone when

he passed by the sixth heaven. Perhaps with time he may have risen

somewhat nearer to his Lady.

Translation: Ann Farrow