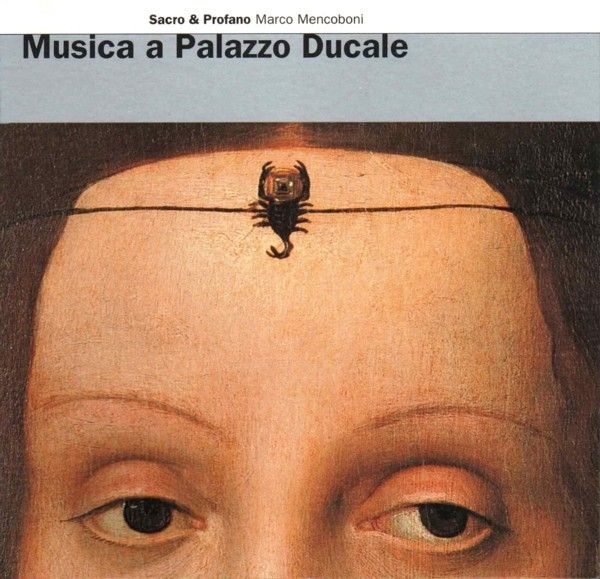

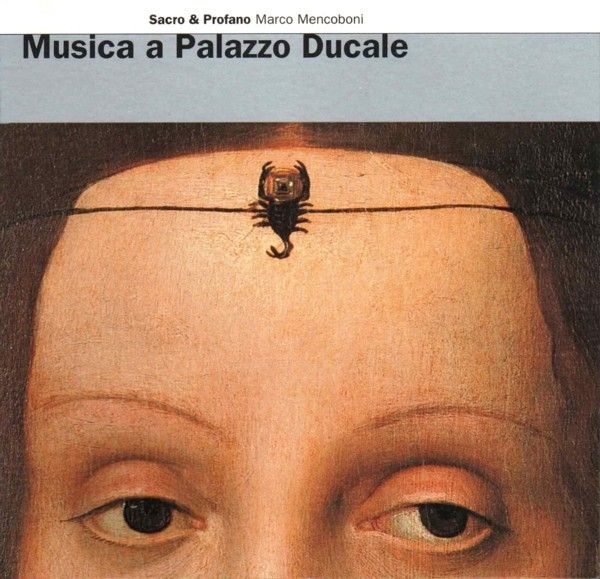

Musica a Palazzo Ducale

Sacro & Profano

elucevanlestelle.com

E lucevan le stelle CD EL 972307

1997

luoghi di registrazione:

Villa Montani · Ginestreto, Pesaro

Chiesa di S. Agostino · Corinaldo, Ancona

Monastero SS. Salvatore · Fucecchio, Firenze

Guglielmo EBREO da PESARO (ca.1420-ca.1484)

01 - Leoncello [3:10]

02 - Petit Vriens [1:57]

03 - Voltati in ça Rosina [1:27]

Anonimo (XV-XVI sec.)

04 - Japregamore (J'ay pris amour) [2:55]

05 - Bassadanza [4:06]

06 - Tanto me desti [0:57]

Francesco SPINACINO (XV-XVI sec.)

07 - Ave Maria de Josquin [2:48]

Pietro PACE (1559-1622)

08 - Ave Maria [2:28]

09 - Qualis est [2:33]

10 - Cum invocarem [1:43]

11 - Ingredere [2:32]

12 - Ecce domum [2:33]

13 - O quam speciosa [2:35]

Vincenzo PELLEGRINI (XVI sec.-1631)

14 - Canzon la Gentile [1:51]

Bartolomeo BARBARINO 'Il Pesarino' (ca.1565-?)

15 - L'ombre crudeli e sorde (intavolata) [3:05]

16 - M'é piu dolce il penar [2:00]

17 - Son morto hai lasso [3:37]

18 - Ridete pur ridete [2:26]

19 - S'ergano al cielo [2:08]

20 - Serenissima coppia [2:17]

21 - S'avvicina il partire [2:53]

Vincenzo PELLEGRINI

22 - Canzon la Berenice [2:20]

Ignazio DONATI (1575-ca.1638)

23 - Ecce tu pulchra es [3:34]

24 - Benedictus Deus [3:28]

25 - Salve regina [4:44]

26 - Beatus vir [4:24]

Sacro & Profano

Marco Mencoboni

Andrea Damiani, liuto rinascimentale · #1-7

Rosa Dominguez, soprano · #8-13, 16, 17, 21

Roberta Invernizzi, soprano · #9, 10, 12, 13, 23, 25, 26

Nadia Ragni, soprano · #9, 10, 11, 13, 23, 25, 26

Roberto Balconi, controtenore · #11, 12, 26

Gian Paolo Fagotto, tenore · #18, 20

Antonio Abete, basso · #10, 12, 19, 24, 26

Andrea Damiani, chitarrone · #9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Eduardo Egüez, tiorba e tiorbino · #15, 16, 17, 18,

19, 20, 21

Marco Mencoboni, organo e clavicembalo

Raffaello Sanzio

Raffaello Sanzio was born in Urbino in 1483. His early years were spent

in the shadow of his father, Giovanni Santi, painter, poet, courtier

and man of culture. From his youth Raffaello was fascinated by the

works of art and beautiful decorations of the palace in which he lived.

Under the tutelage of Perugino, he refined his techique in Perugia and

elsewhere, growing to artistic maturity before the end of the century.

In 1504 he was employed in Florence, his all too brief career being

divided, perhaps too schematically, into two segments: the period until

1508 which he spent in Florence, and the period in Rome, which

culminated with his death in 1520. Above all, during the latter period

when he was employed by the great papal patrons in the Vatican palace,

Raffaello made a dramatic impression on the world of Art. While it is

true that he, together with Michelangelo, created the style we now

identify as Mannerism (which would influence both Italian and European

Art in all its variations for any decades), it is also apparent that

the true gift of Raffaello was his classicism, which derived from a

lively understanding of the style revealed in the ruins of ancient Rome.

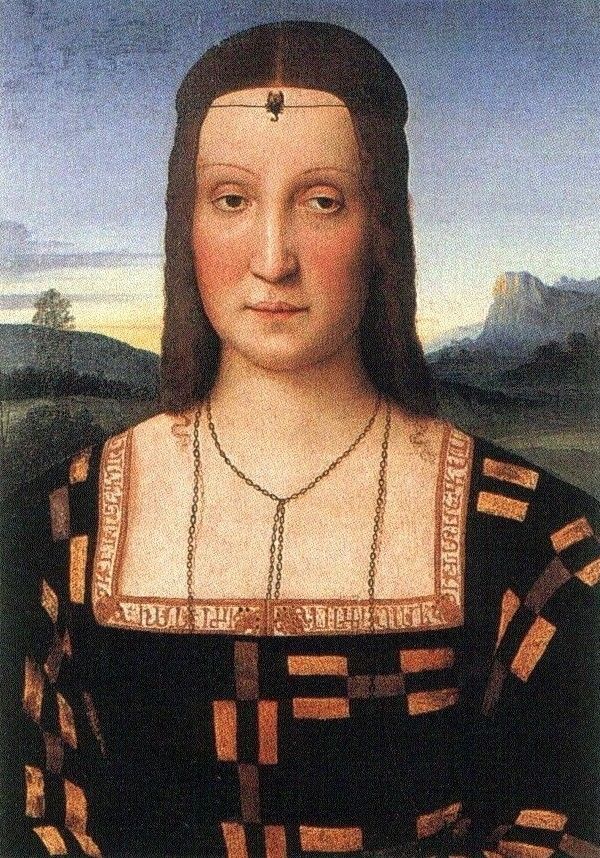

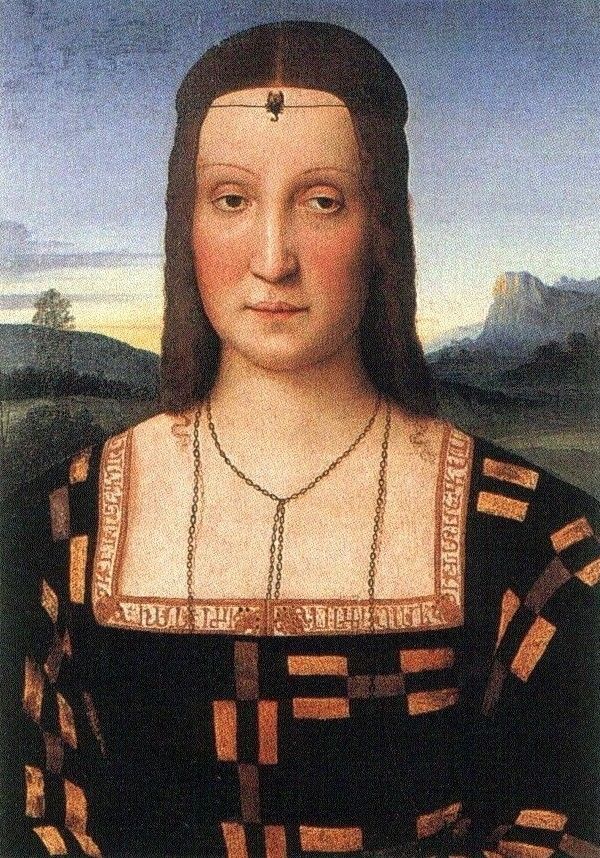

The splendid Portrait of Elisabetta Gonzaga is essentially

classical. Although now conserved in the Uffizi gallery in Florence, it

was originally commissioned from the 'divine' painter by the rulers of

Urbino, and for more than a century it hung in the Ducal Palace of

Urbino. The painting portrays the bride of Guidobaldo I of Montefeltro,

who animated festivities and inspired the lively conversations

described by Baldassarre Castiglioni in Il Cortegiano.

Portrayed in a pose of noble melancholy, sweetly idealised and

displaying the jewelled symbol of the scorpion, she is dressed in

bridal raiments which are surprisingly modern to our eyes, dominated by

assymetrical rectangles of silver and gold, while the background is a

moody landscape cloaked in shadow, illuminated by the rays of the

setting sun.

Paolo Dal Poggetto

Superintendent of the Artistic and Historical Patrimony of the Marches,

Urbino

Music at the Ducal

Palace of Urbino

This is the first of what is hoped to be a long series of publications,

studies and performances of music at the court of the Montefeltro and

Della Royere families in Urbino and in other cities in their domains,

examining the relationship between the ruling families and musicians of

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as the existence of

various other sources of musical commission in the areas of Urbino and

Pesaro.

The palace of the Montefeltro family in Urbino today houses the offices

of the authorities responsible for safeguarding local art works. One of

the principal objectives of the authorities is to make the stupendous

palace available to the public, and, at the same time, to promote the

National Gallery of the Marches by purchasing works of art by local

artists or by artists who once worked in the area. At the same time, in

the absence of a specific authority dedicated to music, the authorities

take great pride in promoting music which was written for the Marches

and Urbino, by financing (within their limited means) musicological

research and the performance of rare and often unpublished music. And

so it gives us great pleasure to have supported the research of Marco

Mencoboni, who has focused his attention for many years on music of the

seventeenth century and earlier which was commissioned by the courts or

churches of the Marches.

The active exchange between the authorities and maestro Mencoboni began

some time ago, as a result of the concerts which he performed in the

Palace during the last two editions of the Fine Arts Week. It is worth

remembering that for more than a year now Baroque music has been

broadcast for an hour every day in the Ducal Palace, an event which

stands alone in the chronicles of Italian museums.

To help defray the not indifferent costs of producing a compact disc of

such quality in a musical sector which is still little known, Poltrona

Frau of Tolentino came forward, and I would like to thank the

company personally for its great generosity. The music has been

exquisitely performed on this recording by Sacro Profano, directed by

Marco Mencoboni, while the introductory essay is fruit f the research

of Prof. Franco Piperno of the University of Florence, to whom we are

also extremely grateful.

This recording is intended as a foretaste of the delights in store of

the Della Rovere musical world, which will be completed - and this

dream is not mine alone - by bringing to light that fascinating opera

by Pietro Pace, the Ilarocosmo, which is full of symbols and

Baroque effects, and is noteworthy in the first instance for its

scenography, which included personification of the Rivers and he Trees

(clear references to the members of the Della Royere family).

The opera was composed in 1621 on the occasion of the marriage of

Federico Ubaldo, the last of the family line, to Claudia de' Medici, a

union intended to join the two great families. Unfortunately, the opera

was never performed, as a consequence of the State mourning imposed by

the sudden death of the bride's brother. At the same time, the

religious music of Pietro Pace is well-represented on this cd. Pace was

the maestro di cappella in Loreto, and was often present at the

court of Pesaro and, we can only suppose, at the court of Urbino too.

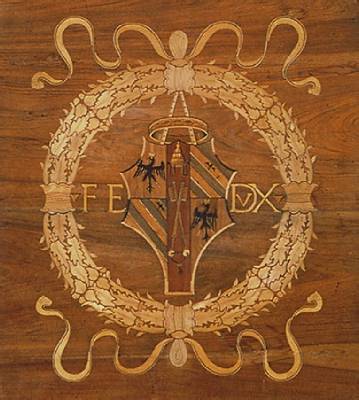

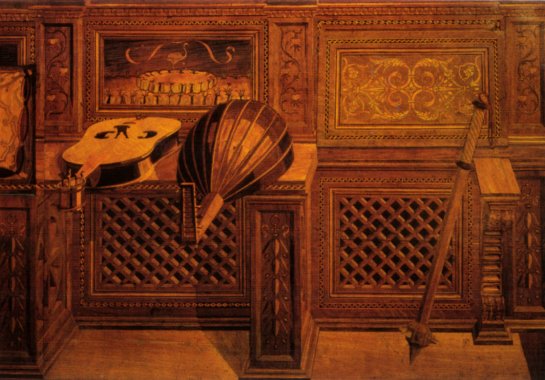

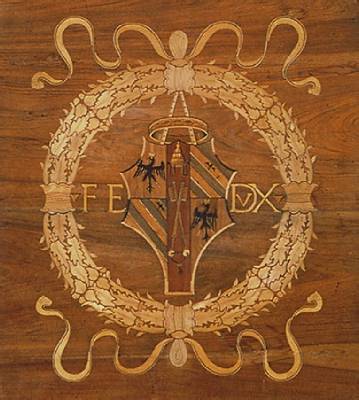

This recording also provides a rare example of music from the fifteenth

century, the chanson 'J'ay pris amour', which was also represented in

the wooden inlay carvings of Duke Federico's small private study in

Urbino, and which seems to suggest that it was one of his favourite

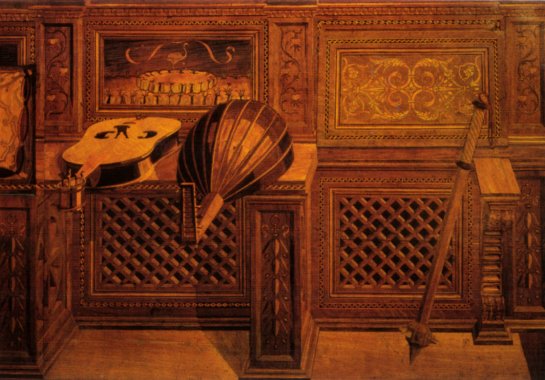

pieces. Music was an integral part of courtly life throughout the

sixteenth century, and even earlier, and it was of particular

importance in the courts of the Montefeltro and Della Rovere families,

and this fact is clearly evident in the numerous paintings which adorn

the palace, as well as in the decorations of the building itself.

Alongside the inlay carvings already mentioned, we need only think of

the splendid 'Apollo' which animates the great door leading from the Sala

degli Angeli (Angel Room) to the so-called Sala del Trono

(Throne Room), the room where banquets and balls were held. Of equal

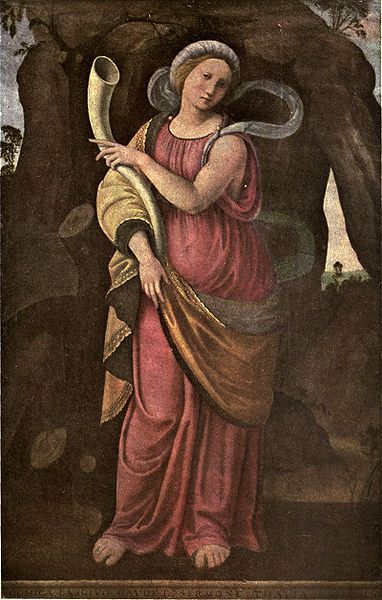

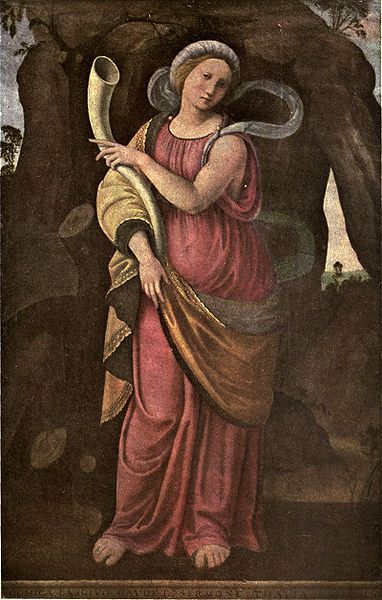

importance, the representation of 'The Muses', which were painted by

Giovanni Santi and Timoteo Viti for the decoration of the Tempietto of

the same name in the public area on the ground floor of the Ducal

Palace. These are conserved today (though only in part, unfortunately)

in the Corsini Gallery in Florence. Each figure was distinguished by a

musical instrument - the lute, the organ, and the trumpet, for example.

And even while the sound of music diminished in the palace, as the

morbid and gloomy 'Spaniard', Francesco Maria II, meditated painfully

on the impending extinction of his house, the prince's favourite

artist, Barocci, painted a 'Saint Cecilia' for the cathedral of Urbino

which includes a moving evocation of musical instruments, a portable

organ negligently held upside down being one of the delightful features

of the work.

While all, or almost all, the pieces of music performed on this

recording were once heard in the Ducal Palace of Urbino (many, indeed,

were expressedly commissioned by the Della Rovere family), it is more

problematical to hypothesise with certainty the rooms of the palace

which were set aside for musical entertainment. It is very probable,

though not absolutely certain, that music was played in various parts

of the palace: apart from the Throne Room - a space which was used for

receptions and concerts - the Audience Room on the first floor, and the

Banquet Room on the ground floor were used for performances by visiting

musicians, or by artists invited to play in Urbino by Federico, or in

Pesaro and other ducal residences throughout the sixteenth century by

his successors. Federico counted many musicians among the paid members

of his court, and I hope that we will soon have more precise details of

their names, the instruments on which they excelled and the music which

the Duke requested them to play, apart from the famous O rosa bella

or his beloved J'ay pris amour.

Paolo Dal Poggetto

Music at court from

Montefeltro to Della Rovere

The court: a place to live, a place of power, of pageantry, centre of

entertainment, a place of private plotting and public ceremony. And in

the background, an underlying tapestry, music: sometimes ornamental,

often a symbol of aristocratic splendour, accompanying the various

activities of the prince and his courtiers, a muted but incisive

element in the halls of the palace, a seductive and emblematic

presence, representing the extemporary character of the place itself

and its rituals, reflecting also an instinctive reluctance to commit

anything to paper.

The Italian Renaissance rediscovered and reassessed the Platonic notion

of the regenerative power of music, an integral feature of the

representation of perfect government and the prosperity of the state:

the humanist prince is, therefore, by definition interested in music,

surrounding his person with its symbols and taking every opportunity to

associate music with the occasions in which he exercises power, whether

in public celebration or for his private delight. In the latter part of

the fifteenth century, Urbino came to exemplify this philosophy.

Marsilio Ficino considered Federico of Montefeltro to be an ideal

prince governing an ideal city, while Vespasiano of Bisticci,

Federico's biographer, insists on the culture and the musical

refinement of the Duke of Urbino, a fact which he omits to mention with

regard to other protagonists of his Lives: "the Duke was

greatly pleased by music and knowledgeable both of singing and of

playing, and had a cappella di musica containing the most

excellent musicians [...] there was hardly an instrument which he did

not have in his court, nor one in which he did not delight, and he

employed the most expert players of many instruments [...]". The palace

of Urbino was enriched in Federico's time with decorations (frescoes,

bas reliefs, sculptures, wooden inlay work) which remind the visitor

continually of the Perfect alliance of music, culture and politics

which reigned there.

As recent studies have demonstrated (N. Guidobaldi), the role of music

as a symbol of enlightened government reached extraordinary heights in

Urbino with regard to the decoration of various parts of the palace,

particularly the private study of the prince, and in the room which

once contained the Allegory of Music by Giusto of Gand,

together with three other allegorical subjects (representing Argument,

Astronomy and Rhetoric). In the private study, the iconography refers

to the daily importance of music in the court, representing objects

belonging to the Duke and used by his musicians, as well as indicating

their repertoire: the music of J'ay pris amour, a popular

chanson which is inlaid in one wall of the study, and which was used

during the feast celebrating the arrival in Urbino of Federico of

Aragon, a powerful ally of Montefeltro, undeniable testimony of a

significant political occasion in which music played its part.

Concerning the Allegory painted by Giusto of Gand, a figure kneeling

before the Muse, traditionally held to be Costanzo Sforza, Lord of

Pesaro, has been recently identified as the dancing-master, Guglielmo

Ebreo of Pesaro, the most representative musician of the court and most

important choreographer of the Italian Renaissance, whose De

pratica seu arte tripudii vulgare opusculum was dedicated to

Federico, testifying to the importance of dancing at the Court of

Urbino.

Music was used inevitably in the context of feasts, whether of dynastic

or diplomatic importance, and carnival entertainments, as well as for

private enjoyment by the Prince. The names of some of the performers

have survived in contemporary documents: Pietrobono dal Chitarrino, for

example, a lutenist from Ferrara, who was one of the most renowned

performers of the day. Many other names have been lost, their role

remembered, however, in the iconography mentioned previously. The

musical repertoire was in the most elaborate French style (Binchois,

Dufay, Okeghem, Dunstable, Ciconia), although it also included Italian

pieces of note, such as the well-known, O rosa bella, of which

two arrangements exist, one in Vatican Codex Urbinate 1411, which once

formed part of Federico's library, the other in an inlay panel from

another (dismantled) study of the Duke in the palace of Gubbio, which

is now conserved in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. Gubbio was

greatly loved by Federico and he built a palace here, a sort of minor

branch of the palace in Urbino, both in its use and for the presence

there of music: the employment and the meaning of the musical arts

within a princely court stretched out from the capital city and

extended to every place in which the prince chose to reside, even on a

temporary basis. This was the singular prerogative of the dukes of

Urbino (the Montefeltro family in the first instance, the Della Rovere

dynasty afterwards), and it is unequalled in other courts, where

musical patronage rarely went beyond commissioning music for civic

occasions, or, more rarely, for entertainment and pleasure. By

contrast, in the Dukedom of Urbino courtly music was heard by the

Duke's expressed wish in all of the smaller centres too: first in

Gubbio and Casteldurante, then in Pesaro which would later become the

capital city), in Fossombrone, Senigallia and Cagli, to the extent that

the term 'court music' should not be restricted simply to the capital

city.

The tradition is even more strongly represented in the Della Royere

dynasty which succeeded the extinct Montefeltro line in 1508, when the

adopted son of Guidobaldo of Montefeltro, Francesco Maria I, came to

power. He added the city of Pesaro, of which he was the ruler, to the

Dukedom of Urbino, and thus Urbino gained its first sea-port.

Senigallia soon came under the sway of the Della Rovere family, and it

was to become the most important commercial centre of the Dukedom. In

the 1520s Pesaro was chosen as the new capital of the Dukedom, Urbino

being used as a summer residence for the court, though occasional

visits were made to Casteldurante and Mondavio for the purpose of

hunting, while musical and literary occasions were celebrated at the

Imperial palace. Eleonora Gonzaga, Francesco Maria's wife, chose

Fossombrone as her favourite residence after the death of her husband

in 1538, while their son, Guidobaldo II, began to enlarge and decorate

the palace of Pesaro, extensively rebuilding the city, as well as

ordering the construction of the fortifications in Senigallia.

Guidobaldo's brother, Giulio Della Rovere, Cardinal of Urbino, selected

the Red Court of Fossombrone as his favourite residence. This is the

reason why there are so many Urbinate palaces in the sixteenth century,

all of which enjoyed the artistic patronage of the family, a distinct

preference being shown for musical entertainments.

The renowned lutenist, Joannangelo Testagrossa, came from Mantova to

serve Duke Francesco Maria in the palaces of Pesaro and Urbino; Antonio

Cavazzoni came to entertain the sick Duchess Eleonora in 1525 and he

returned in 1533 to supervise the carnival celebrations; the organist,

Giaches Brumel, won widespread admiration for his virtuosity in the

summer of 1534, returning to Pesaro once again in the Spring of 1562;

the carnival of 1544 was marked by the presence of Antonio dal

Cornetto, who was loaned to Guidobaldo by the Duke of Ferrara, while in

the same year the most important of contemporary Flemish musicians,

Domenique Phinot, was 'recommended' to the town council of Pesaro, and

employed by the Duke himself directly afterwards; another Fleming,

Olivier Brassart, was in the service of Cardinal Giulio, while Monaldi

Atanagi, singer, dancer, 'cembalist' and clown, made his appearance in

Fossombrone, Casteldurante, Urbino and Pesaro; the Imperial theatre and

the private quarters of the Palace of Pesaro heard the enchanting voice

of the 'mermaid', Virginia Vagnoli, accompanied by court musicians such

as Paolo Animucci, the organist Giachet Bontemps, the lutenist Stefano

de' Ferrara, and the bass Paolo Pighini, as a letter by Ludovico

Agostini of Pesaro, one-time fiancé of Vagnoli, recounts in his

unpublished manuscript, Giornate soriane (ms. 191, Biblioteca

Oliveriana, Pesaro). Music was heard throughout the territories of the

Dukes of Urbino, not merely in the palace of Urbino itself, which

tended to be ignored by the Della Rovere family as a residence, but in

all of the palaces which came under their patronage; music in the form

of private or public entertainment.

This golden age came to an end in the latter sixteenth century in the

reign of Francesco Maria II who ruled as Duke from 1574 until his death

in 1631, the line dying out with him. Music played a less important

role in his reign and fell silent in the end, its place taken by study,

literature, the collection of books, and philosophical and religious

meditation. One of the final acts in this decline was the performance

of Torquato Tasso's L'aminta in Pesaro during the carnival of

1574, soon after its first performance in Ferrara.

The impulse was provided by Lucrezia d'Este, the refined and,

unfortunately, neglected first wife of Francesco Maria. The performance

was directly personally by the author himself, who may, perhaps, have

heard some of the musical works which were published in 1598 by Simone

Balsamino of Urbino under the title Novellette a sei voci, with

a dedication to the Duke and the citizens of the city. A musical

entertainment by Ignazio Brace and Pietro Pace, L'Ilarocosmo, o sia

il mondo lieto, was planned to celebrate the marriage in 1621 of

Federico's heir (by Livia Della Rovere, his second wife) to Claudia de'

Medici, though it was never performed, and Federico Ubaldo died

tragically in 1623, eight years before his father. This missed musical

opportunity would have been the first instance in the Marches of a new

type of theatre, accompanied melody (i.e., operatic melodrama), which

had been perfomed for the first time and with success in Florence and

Mantova only a few years previously.

If music was muted at the court, it continued to be heard in the

private residences of the nobles, who began to take the place of the

Duke as patrons. Ippolito and Giuliano Della Royere, natural sons of

the Cardinal of Urbino, the Bartoli, Gallo, Albani, Bonamini,

Barignani, Almerici, Mario and Accorimboni families became the new

patrons at the end of the sixteenth century, and in the early years of

the seventeenth century their palaces resounded to the notes of the

most important musicians of the time, Pietro Pace of Loreto, Bartolomeo

Barbarino of Fabriano and Galeazzo Sabbatini of Pesaro, while the halls

of the Dukes fell silent forever.

Franco Piperno

The Composers

Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro, dancer and musician, was born around

the year 1420 in Pesaro. His father, Mosè di Sicilia, was

dancing-master at the court. Guglielmo entered the service of

Alessandro Sforza, the ruler of Pesaro, and he was present in Urbino at

the wedding of Federico da Montefeltro, whose service he entered after

Alessandro's death. He wrote an important treatise, De pratica seu

arte tripudii (1463), which has survived in numerous editions and

describes the choreography of contemporary dancing and the recommended

method of playing the accompanying instruments.

The pieces by an unknown composer presented here are all taken

from the chord-form manuscript which is conserved at the Biblioteca

Oliveriana in Pesaro. The volume is quite exceptional, not only on

account of its musical contents, but also for the information of

historical and cultural value which it contains. The volume was

compiled over a period of almost two hundred years and is a compendium

of the music played in this geographical area. The collection of pieces

for lute includes Japregamore (J'ay pris Amour) which is the

instrumental version of a well-known song which was popular throughout

Europe, and which Duke Federico da Montefeltro chose as a wooden inlay

motif for his private study in the palace of Urbino.

Two books of lute entablature by Francesco Spinacino (XV-XVI

century) were published in Venice in 1507 by Ottaviano Petrucci of

Fossombrone, the first ever to have been published. The printing was a

refined technical procedure which began with the musical stave, adding

the note numbers and elaborate headings in successive phases. As such,

the publications are among the most precious examples of the printer's

art. Information about the composer's life is restricted to what can be

gleaned from these editions. The composer was probably a fellow-citizen

of Petrucci, perhaps of noble birth, certainly a lute virtuoso. Verses

written in praise of his playing suggest that his name was derived from

the word 'spina' or 'thorn' (which was used as a plectrum), exciting

the ear without injuring the hand. Spinacino's art is closely tied to

the lute tradition of the latter part of the fifteenth century.

Pietro Pace was born in Loreto in 1559, and performed as

organist at the Santa Casa of Loreto from 1591 to 1593. He was employed

at Pesaro in 1597, and returned to Loreto in the period from 1611 to

1622. He also served the della Rovere family. His Quinto libro de

motetti, op. 10 which was published in 1615, was written as the

frontispiece suggests, "in praise of the Most Glorious Virgin Mary"

while he was employed at the Santa Casa of Loreto. It was dedicated to

Sister Maria (Eleonora) della Rovere, to whom he had given musical

instruction when she was a child, and included compositions for one to

six voices.

Born in Pesaro, canon of the Cathedral and probably an organist, Vincenzo

Pellegrini (second half of the sixteenth century-1632) was

appointed Maestro di Cappella to the Cathedral of Milan, where

he remained until his death. His collection of Canzoni di

intavolatura d'organo fatte alla francese (Venice 1599) was

dedicated to Livia della Rovere, the bride of Francesco Maria II, Duke

of Urbino. The works employ counterpoint and anticipate a style which

was increasingly popular in that period. The compositions are

constructed in various sections which use contrasting types of musical

writing (chordale or imitative), as well as different tempos and rhythm.

Bartolomeo Barbarino, who was known as il pesarino, was

born in the town of Fabriano in the Marches. He first came to public

attention in 1593 or 1594 as a counter-tenor singing in the choir of

the Santa Casa of Loreto. By 1602 he had been called to the service of

Monsignor Giuliano della Royere in Urbino, and he also appears to have

been employed in the same period by the Duke of Urbino, as the composer

mentions in the dedication of his published collection of madrigals in

1604. He was one of the first to write songs for a single voice and was

one of the most enthusiastic proponents of this particular musical

form. Indeed, almost all of his compositions, whether written for

performance in the church or in the court, belong to this genre.

Ignazio Donati was born in Casalmaggiore around 1575. He was

active in the Marches in the cities of Urbino, Pesaro and Fano, before

moving to the north, where he ended his career as Maestro di

Cappella at the Milan Cathedral from 1631 to 1638. He was the

inventor of a praxis known as Cantar lontano, which consisted

of polyphonic vocal effects produced by the positioning of various

groups of singers at a distance from one another.

Sources

Anonimo

Biblioteca Oliveriana, Pesaro, MS 1144

Francesco Spinacino

Intabolatura de lauto Libro I, Venezia, Ottaviano Petrucci, 1507.

Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro (Giovanni Ambrosio)

De pratica seu arte tripudii, Paris, Bibliothèque

Nationale, fonds ital. 476.

Domenico da Piacenza, De arte saltandi et choreas ducendi,

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds ital. 972.

Vincenzo Pellegrini

Canzoni de intavolatura d'Organo fatte alla francese, di Vincenzo

Pellegrini canonico di Pesaro, libro primo, Venezia, Giacomo

Vincenti, 1599.

Pietro Pace

Il Quinto libro de Motetti a Una, Due, Tre, Quattro, & Cinque

voci in lode della gloriosissima Vergine Maria con il suo basso per

sonar nell'organo. Di Pietro Pace organista di Santa Casa di Loreto.

Opera Decima, In Venezia, appresso Giacomo Vincenti, 1615.

Bartolomeo Barbarino

Madrigali di diversi autori posti in musica da Bartolomeo Barbarino

da Fabriano per cantare sopra il chitarrone, clavicembalo o altri

instrumenti da una voce sola, libri primo e secondo, In Venetia

appresso Ricciardo Amadino, 1606.

Ignazio Donati

Ignatii Donati Ecclesiae Metropolitanae Urbini Musicae Praefecti.

Sacri Concentus unis, binis, ternis, quaternis, & quinis vocibus,

una cum parte organica, Venezia, Giacomo Vincenti, 1612.