This recording is subtitled "Living Traditions of the Orient" and is supposed to be followed up with

"Medieval Spain and the Hispanic tradition."

The present recording reflects the dual diaspora: toward Turkey in the East,

or remaining in the Western Mediterranean, and is reflected today in two distinct modern traditions.

And keep in mind that this music is distinctly modern.

The opening track, for instance, is audibly influenced by the Turkish styles of Central Asia, i.e. completely post-Ottoman.

There is a nice range of styles here, reflected both in the vocal tone and the instrumental accompaniment."

— medieval.org

The Balkans and the Ottoman Empire

SARBAND

"Since

the earliest days of our youth we have been accustomed to living in a

supernatural universe. In our ghettoes, somewhere in the endlessness of

the Maghreb, from Djerba to Rabat and Marrakesh, from the High Atlas to

the Sahara at the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts, the visitor, upon

entering our low dwellings at the end of often narrow alleys, full of

wooden shacks where merchants or craftsmen, crouching on the ground,

were performing the same or virtually the same tasks as those which had

been customary in the East in Biblical times, was immediately overcome

by I know not what manner of Biblical fragrance of the Orient..." (André

Chouraqui, from: Ce que je croix)

Vladimir Ivanoff

Vladimir Ivanoff

SARBAND Translation: Janet & Michael Berridge

Ⓟ 1996, JARO Medien • © 1996, BMG Music

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) 05472 77372 2

1996

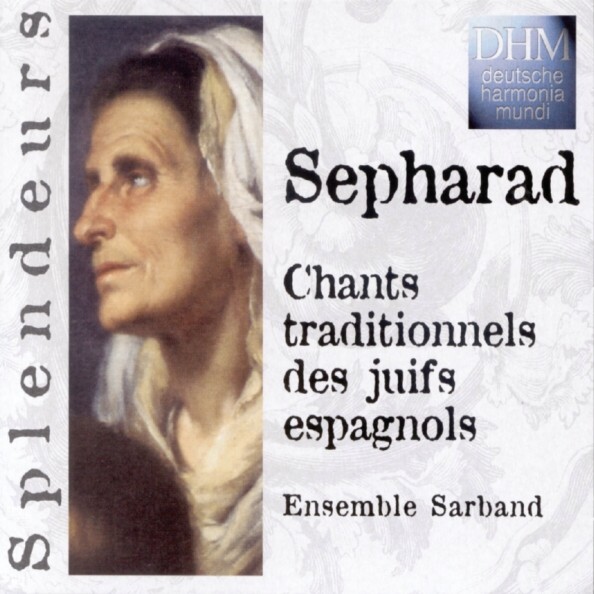

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) "Splendeurs" 93564

I. Living Traditions of the Orient

[II. Hispano-arabic Tradition of Medieval Spain]

Wedding song · Cantica de boda (Plovdiv, Estambul, Sarajevo)

1. [7:52]

Una ramika de ruda — Hochzeitslied / Bulgarien: Plovdiv

Una matika de ruda — Hochzeitslied / Türkei: Istanbul

Una matika de ruda — Hochzeitslied / Bosnien: Sarajewo

This,

perhaps the most popular of all Sephardic wedding songs. has survived

in nearly all the Sephardic colonies, with the most diverse tunes. All

of the different versions feature one basic element which never changes:

the wine rue twig, which deflects the "evil eye" and is therefore meant

to bring the newly-weds luck.

Romance (Bulgaria) — Nana (Bosnia)

2. [9:47]

A kasar el rey — Romanze / Bulgarian – Bosnien

Anderleto — Wiegenlied / Bosnien

Various

versions of this old romance are known in nearly all the Sephardic

communities; from Jerusalem via Asia Minor, Bursa, Istanbul, Rhodes to

Sofia. The story is based on the legend of Landarico (Anderleto), the

Merovingian princess Fredegunda's servant. It tells the story of a Queen

who has fallen in love with her servant Anderleto. She bears him twin

sons, while two other sons are the King's children.

Assuming that the

King is out hunting, she sings her four children a lullaby, which is

simultaneously a love song to her slave. The King plans to surprise her;

instead of hunting he creeps secretly into the Queen's bedroom and as

she mistakes him for Anderleto, he is party to her love-song to her

servant and the two children the slave has fathered her.

The

beginning of the tale, of three verses and with its own tune, is in the

Bulgarian-Sephardic tradition. The other verses are after the Bosnian

manner.

Nana (Bosnia)

3. Morikos [4:38]

Wiegenlied / Bosnien: Sarajewo

The

beginning of this ballad is contained in the songs "La reina Xarifa"

and "Las hermanas reina y cautiva" (The two sisters, Queen and prisoner,

from Thessaloniki, Greece): the Moorish Queen of Almeria orders a raid

on Christian territory in order to procure a female slave of noble

birth. The opening verses of "La reina Xarifa" set the scene and explain

the story.

The Queen's Moors take a Countess prisoner and kill her

husband, Flores. Later the Queen and the Countess both give birth on the

same day and the Queen acclaims the slave as her sister, when she sings

her child a lullaby.

The end of this verse conforms with the beginning of the Bosnian romance — "Morikos.- Many geographical and historical

coordinates of the story were lost in the Bosnian tradition.

Nana (Turquía, Grecia)

4. Nani nani [6:12]

Wiegenlied / Türkei – Griechenland

A

lullaby in the Turkish tradition with a tune in Makam Hijaz. Additional

verses in other surviving versions of the song reveal the father of the

child to be the man who deceived the mother.

Mediterranean

Romance (España, Marruecos, Orán)

5. [7:52]

Quien huviesse tal ventura —

Diego PISADOR. Libro de Musica de Vihuela, Salamanca, 1552

Gerineldo — Romanze /

Marokko – Algerien: Oran

The Gerineldo

romance is based on a legend from the time of Charlemagne and tells of

the unhappy love affair between Eginard (770-840), secretary and

historian (author of the Vita Karoli) to Charlemagne, and the emperor's daughter.

The

text to Diego Pisador's 16th century vihuela song provides only the

first lines of a ballad. The main character Gerineldo of the Sephardic

tradition is replaced by a Prince Arnaldos. In our recording, this is

followed by the second and third verses of the song, with two different

Moroccan-Sephardic tunes which have survived with this story, and then a

version of the romance from Algeria. The outline of the original

Spanish melody, as passed on by Pisador, has been wholly preserved in

the two Moroccan versions, while in the probably more recent version

from Algeria the original tune has undergone a shift to tonality.

Romance (Tesalónica, Tetuán, Alcazarquivir)

6. Abenámar [5:22]

Romanze / Griechenland: Saloniki – Marokko: Tetuan, Alcazarquivir

This

romance, which has only survived in fragments, was originally sung in

Arabic. It tells of the Arabian prince Abenamar and King John II of

Castille.

In another version of this romance King Juan tries to no avail to exchange the city of Granada for Cordoba and Seville.

Romance (Estambul, Sofía, Tesalónica, Libia, Jerusalén)

7. La rosa enflorese [9:03]

Romanze / Bulgarien: Sofia – Türkei: Istanbul –

Griechenland: Saloniki –

Libyen – Jerusalem

In

many Sephardic communities the religious song (piyyut) "Tsur Mishelo

Achalnu- is sung at the first Sabbath meal on Friday evening to the tune

of this Sephardic love-song.

Vladimir Ivanoff

Fadia El-Hage (Lebanon) — Gesang

Belinda Sykes (England) — Gesang, Schalmeien, Dudelsack

Mustafa Doğan Dikmen (Türkei) — Ney, Kudüm, Gesang

Ihsan Mehmet Özer (Türkei) — Kanun

Ahmed Kadri Rizeli (Türkei) — Kemenge, Perkussion

Mehmet Cemal Yęsilçay (Deutschland, Türkei) — Ud, Djura, Perkussion

Vladimir Ivanoff (Deutschland, Bulgarien) — Perkussion, Ud, Renaissancelaute

Sepharad

The

Sepharad sphere of influence was initially only encapsulated in the

word of the Bible. Its geographical location was as yet undefined, when

Genesis began its way and the Israelites left the land of their fathers.

Over the centuries the term "Sepharad" gained in cultural, religious

and historical significance. Since then, in addition to a place of

exile, "Sepharad" has held a promise of a religious conviction and of

cultural self-determination. Over two thousand years ago the Jews fled

from Nebuchadnezzar and the ruins of the Jewish empire and gradually

crossed the Mediterranean. Since Roman times there has been evidence of

Sephardic Jews in the Iberian peninsula. In 589 Christianity was

declared the official state religion by the ruling western Goths.

Exercising repression in the form of forced baptism and death threats,

these new Christians forced thousands of Jews to leave the Iberian

peninsula.

As a result, those Jews who remained behind viewed the

Islamic conquest of Spain in the year 711 more as a liberation than a

threat. In the Muslim state order Jews had the opportunity of rising to

high positions in the government and administration. The Jewish

communities in medieval Spain were therefore strongly linked with the

Muslim emirates and especially with the caliphate of Cordoba. The

Arabian-Hispanic Middle Ages represent an important chapter of Judaic

history. After participating in the Near East in the golden age of

classical Arab culture, Jews played an important role in Spain as

mediators between Arab and Christian culture, and Jewish poetry and

music consequently reached a new pinnacle. In the 13th and 14th century

Jews were also musicians at the Castilian court. Together with Arab

musicians they undoubtedly played an important role in the performance

of the Cantigas de Santa Maria (eleven of which tell of Jewish

life and culture in Spain), compiled by King Alfonso el Sabio (1252-84).

At the court of Sancho IV, in addition to thirteen Christian and

fifteen Arab musicians, the Jew Ismaël played the rota (harp) and accompanied his wife when she danced.

The

14th century, when the Catholic reconquest of Spain made considerable

progress, brought the harmonious cohabitation of Spanish Christians,

Jews and Muslims to an end. The pogroms and persecutions of 1391 led to

mass conversions of Jews and Muslims. The mid-15th century saw the

establishment of the Inquisition, which accused many conversos (those

who had converted from other religions) of practising their original

beliefs in secret.

The exodus of Hispanic Jews began on August 2,

1492: in the course of just a few months it is believed that over

160.000 Jews were forced by the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella

to leave Spain and all Spanish sovereign territories in the most

undignified manner. Many Sephardic Jews fled to French Provence.

Hispanic Jews who had converted to Christianity also settled as late as

the 17th century in Bordeaux, Marseilles and Bayonne, after they too had

been forced to leave Spain and Portugal. Many Sephardim sought to start

a new life on the north African coast. The majority however, 60,000 or

more in number, found haven in the sovereign territories of the Ottoman

Empire: in Constantinople, Thessaloniki, Smyrna, Adrianople (Edirne),

Gallipoli, Ankara, in Egypt, Syria, Palestine and the Balkan states.

Sultan Bayezit remarked on the exodus of the Sephardim thus: "It is said

that King Ferdinand, King of Castille and Aragon, is a clever man, but

by driving the Jews from his own country, he is impoverishing his empire

and enriching mine." Some Sephardic communities were also established

in Italy (Ferrara, Livorno), and after the end of Spanish rule in the

Netherlands (Amsterdam), in Germany, Austria and in the New World.

Sephardic Music: History and Allegory

In

the Diaspora Hispanic Jews handed down their medieval Spanish past -

customs, music and language - in undiluted form. The traditional songs

characteristic of the Sephardic Jews were and still are to this day the romanzas in the Jewish-Spanish tongue - judezmo - which is today sometimes misinterpreted as ladino (this term actually refers to translations from the Hebrew into Spanish: ladinar) and corresponds to djudiyo in the Levante and haketiya

in the Maghreb. The lyrics of these songs recount the lives of Spanish

Jewry and tell of Spanish history. Only a few written examples of this

music have survived from the Spanish Middle Ages. However, in addition

to the images conjured up by Sephardic music taken from medieval

sources, the Sephardims' verbal heritage provides a guide to this

immensely rich musical culture.

The development of Sephardic

music is inexorably linked to the history of Spanish Jews following

their expulsion. After leaving Spain and Portugal the Sephardims settled

in numerous communities in the Mediterranean region. There they sang

their songs brought from Spain and sought to maintain their Spanish

culture. In the new environment, usually far from Spanish influence,

they lived in close communities defiantly keeping their Spanish mother

tongue and glorifying their Spanish past.

Since the song

repertoire was and to some extent still is a significant element of

Sephardic community life, it was possible to preserve their songs over

five centuries. This living tradition, in which the exiles handed down

old Spanish epic stories in late medieval Castilian, was greatly

influenced by the various languages and musical cultures of the

countries in which the Sephardims lived. The Sephardic way of life

eventually blended with local traditions in their host countries. As

early as the Middle Ages Spanish Jews had worked closely with musicians

from other cultures and this tradition was continued seamlessly after

the exodus. Not only were tunes integrated into the performance of

sacred and secular poetry, but many musical elements too, such as the

modal tone system, rhythmic and metric characteristics, melodic

embellishment and cadence forms, all flowed into the traditional

repertoire. In addition, numerous new songs developed which make up the

main body of the repertoire still sung today. By the beginning of the

18th century at the latest the Sephardic colonies of the western and

eastern Mediterranean (Ottoman Empire) formed two clearly

distinguishable and independent cultures. The "western" or north African

was able, due to its geographical proximity, to maintain its ties to

the Iberian peninsula, while the "eastern" camp was to a great extent

exposed to new influences.

It is therefore possible to define two

main traditions within Sephardic song culture, where its repertoire,

melodic structures and performance practice are concerned: that of the

eastern Mediterranean, mostly under Turkish and Balkan (generally

Ottoman) influence and that of the western Mediterranean, which was

significantly influenced by Moroccan and Spanish elements. With Europe's

increasing political and economic influence on the Middle East since

colonization, western musical influences have increased, especially in

northern Africa.

Any formal matching of songs from the western

and eastern repertoires, that is from two independent music traditions

which enjoyed only a minimum of mutual contact, points to the fact that

both traditions have handed down, quite independently of one another,

some of the repertoire and/or characteristics of the medieval Sephardic

romance heritage in Spain. Some Sephardic Jews continued their

emigration from Thessaloniki and Constantinople, the two central

colonies in the Ottoman Empire, to Jerusalem, where an important

Sephardic community developed which even today is still an amalgam of

Palestinian, Turkish and Balkan elements. This accounts for the many

matching features in the lyrics and tunes of the Palestinian and Balkan

songs.

The female voice is dominant in traditional Sephardic

musical performance. Many of the topics featured in the songs are

represented from a woman's point of view, since it was the women who, in

the Diaspora, passed on the Sephardic traditions to their daughters.

Today the singers further the living tradition, accompanying themselves

on the frame drum or pandeiro. The Spanish monk Andrés Bernáldez

was an observer of the Jews' expulsion from Spain and left the following

lines, documenting the important role of women in Sephardic singing

tradition: "They left the country in which they were born. Great and

small, young and old, on foot, donkeys or in carts, each followed the

path to his or her chosen destination. Some stopped at the wayside, some

collapsed from exhaustion, others were ill, yet others dying. No fellow

creature could have failed to have pity on these unhappy people. All

along the way there were constant appeals for them to accept baptism,

but their rabbis instructed them to refuse and implored the women to

sing, beat their drums and to uplift their souls."

Later, in the

Diaspora, the Sephardic romances were adapted, some of them by

professional, usually male, Jewish musicians and performed in coffee

houses and taverns. In the same way, sacred texts such as the piyyutim were - and still are - set to romance tunes.

The Romance

In

Spain as early as the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance the romance

or ballad was a very popular song-form. It originally survived as a folk

song handed down in verbal form and was only introduced to the Spanish

court towards the end of the 15th century. Like most Sephardic romances,

especially those handed down through the eastern scion, the 15th

century romance, as described in various documents including the Cancionero

musical de Palacio and (described as a romance viejo) in the tablatures

of 16th century vihuelists, has a mainly poetic 16-syllable structure

with assonant rhymes and a musical form with four phrases of equal

length.

The first musical phrase often has an arched, rising and

then descending melodic contour: sometimes, we encounter a purely

ascending melody line. The second melodic phrase is usually higher and

touches the melodic highpoint. These two melody lines are seldom

identical. The third melodic section then descends through an extensive

tonal arc to the deeper cadence. The fourth phrase of limited tonal

extent often ends the melody in a cadenced downward movement.

Many of the melodies are based on a descending chromatic tetrachord which is also characteristic of the musiqà andalusiyya. In the eastern Mediterranean region melodies can often be attributed to the modes (makamât)

of Islamic musical culture: the Hüsseynî, Ushâk, Bayâti, Hicâz,

Hicâzkâr, Púselik, Nihâvent and Ferahfeza modes are frequently

encountered. In the western Mediterranean, especially in Morocco, the

diatonic principle was applied to the melodies, probably under later

European influence, and they were made to conform with major-minor key

tonality.

In the rhythmic-metric performance of the romances

metric and non-metric sections are often interwoven. The eastern

tradition reveals a strong tendency towards a performance completely

devoid of metric and rhythmic constraints, while in the western Moroccan

repertoire the abrupt shift from binary and tertiary metre is popular.

Choice of works

I. Living traditions of the Orient

The

songs chosen by SARBAND for the first section of the journey through

the Sephardic world are still to this day an integral part of

traditional Judeo-Hispanic female singing: cradle songs, wedding songs,

songs of the kitchen. Nevertheless, the repertoire of the 19th and early

20th centuries is also included: salon romances and popular coffee

house songs from the Orient, inspired by the contemporary Andalusian copla.

II. Medieval Spain and the Hispanic tradition

In

the second section of our journey through time and cultures the

significance of Judaic musical culture in the preservation and dynamic

modification of medieval Spanish romances on the one hand and of the

Arab-Andalusian muwassahat and harjas is demonstrated by

means of the various compositional modes. It is our aim to create a

living audio document of the former symbiosis of medieval story-telling

of north Spanish, Andalusian or HispanicJewish origin with oriental

melodies from Asia Minor or the Balkans: the sphere of influence of

"Sepharad".

Thanks

Without the basic research,

collections of documents and publications of Léon Algazi, H. Anglés,

Samuel G. Armistead, Hanoch Avenary, Avner Bahat, Eugène Borrel, Judith

Cohen, José Antonio de Donostia, Judith Etzion, Edith Gerson-Kiwi,

García Gómez, Alberto Hemsi, A. Z. Idelsohn, Israel J. Katz, Isaac Levy,

Leo Levy, Benjamin M. Liu, Manuel Manrique de Lara, Michael Molho,

Eduardo Martines Torner, Ramón Menéndez Pidal, James T. Monroe, Joaquín

Rodrigo, Edwin Seroussi, Amnon Shiloah, Joseph H. Silverman, Samuel

Miklos Stern, Susana Weich-Shahak, David Wulstan, Henrietta Yurchenco,

Rodrigo de Zayas, to mention just some of the researchers, our journey

through the history of Sephardic songs, which is meant to be a creative

new study on the basis of the numerous sources which have emerged over

the past hundred years, would not have been possible.

"Sarband"

is a term from Persian and Arabic denoting the improvised connection of

two parts within a suite. Vladimir Ivanoff, who founded the ensemble in

1986, pursues an archaelogy of complex connections. Sarband aims above

all to demonstrate the links between European music, and the Jewish and

Islamic musical cultures. Sensitively, and with great intensity, Sarband

celebrates the symbiosis of Orient and Occident. The inter-reaction

within the ensemble is of a continuous nature, aspiring to an equal

dialogue. Exchange of experience with musicians from different cultures

lends to Sarband's performances the greatest possible degree of authenticity, making them exciting and lively.

In

their performance of medieval music the Turkish. Italian. English,

Bulgarian. Arab and German musicians involved in the project employ a

colourful range of instruments, vocal and instrumental techniques and

the art of improvisation as can still be found today in the Islamic

culture. With its musically unique concert repertoire Sarband has made a name for itself on the international scene. Sarband

has been appearing over the past few years at numerous international

festivals of various leanings, from early music to avant-garde.

The Sarband

musicians do not see their activities as a sporadic venture, but as an

expression of existence and life itself. While in this day and age the

emphasis is usually on the religious, economic, cultural and

political

differences between the Orient and the West, Sarband's musical

performances aim to demonstrate that music at least was not merely an

embellishment, but a liberal-minded medium of mutual respect and can

continue to be such: an example of understanding and mutual recognition,

an example of peace.

Vladimir Ivanoff

Born in

Bulgaria, Vladimir Ivanoff is a qualified musicologist and graduate of

the lute class at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis; he wishes to develop a

link between musical science and actual performance practice, while

revealing the threads connecting the Orient and the West and tightening

them. His dedication to early music does not ossify in awe for what has

been handed down. On the contrary, he breathes new life into the old,

with a conscious desire to integrate present-day experience into the

execution. He puts new spirit into the sometimes rather dry area of

early music without leaving the basis of musicological teaching.

MUSICOLOGY:

studies and doctorate in musicology in Munich - research projects in

Venice - post-doctoral project qualifications in Munich and Venice -

lectureships in musicology, ethnomusicology and historical performance

practice at various universities - lectures at symposia and conferences

in most European countries and the USA; several books published -

numerous contributions to musicology magazines and encyclopaedias.

MUSIC:

Studied the lute and historical performance practice at the

Musikhochschule Karlsruhe and the Basel Music Academy/Schola Cantorum

Basiliensis - percussion training with several traditional musicians -

musical director of the Sarband, Vox. L'Orient Imaginaire projects and

(together with choral director Johannes Rahe) Metamorphoses - concerts,

staged projects, radio, TV and CD recordings in Europe and the USA -

producer (including "Mystère des Voix Bulgares") and head of recording

for many CD recordings of early, traditional, electronic and pop music

(two Grammy Award nominations).

Recording: Jochen Scheffter, Dr. Vladimir lvanoff, Beirut, Istanbul, München, 1994

Post production: Friedrich Them, Dr. Vladimir Ivanoff, Bremen 1994

Musical producer: Dr. Vladimir Ivanoff

Designed by: Ariola/Petra Hirschfeld

Art director: Thomas Sassenbach

Photo and Illustration: White Star

Copyright 1996 BMG Music

All rights reserved