medieval.org

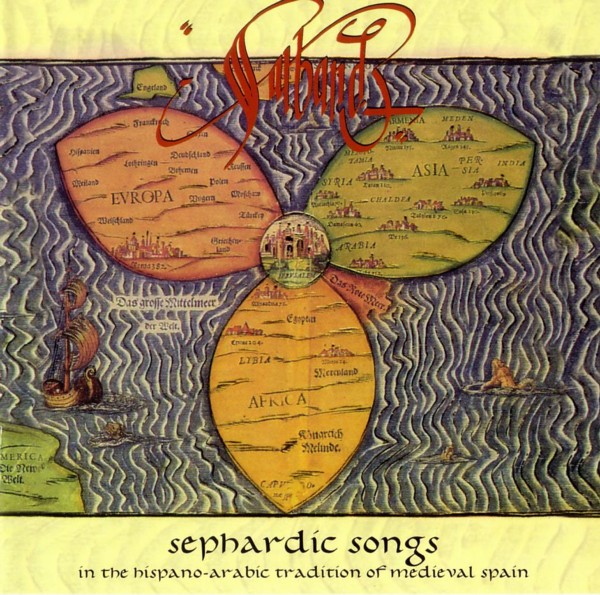

Jaro 4206-2

1996

1998: Sonifolk/Lyricon (Jaro) 21115

"Canciones Sefardíes de la tradición hispanoárabe en la España medieval"

1999: Dorian Recordings DOR-93190

"Ballads of the Sephardic Jews"

medieval.org

Jaro 4206-2

1996

1998: Sonifolk/Lyricon (Jaro) 21115

"Canciones Sefardíes de la tradición hispanoárabe en la España medieval"

1999: Dorian Recordings DOR-93190

"Ballads of the Sephardic Jews"

Sepharad

— Vladimir Ivanoff

Sarband

Without

the fundamental research, collections and publications of Léon Algazi,

Higini Anglés, Samuel G. Armistead, Hanoch Avenary, Amer Bahat, Eugène

Sorrel, Judith Cohen, José Antonio de Donostia, Judith Etzion, Edith

Gerson-Kiwi, Garcia Gómez, Alberto Hemsi, A. Z. Idelsohn, Israel J.

Katz, Isaac Levy, Leo Levy, Benjamin M. Liu, Manuel Manrique de Lara,

Michael Molho, Eduardo Martínez Tomer, Ramon Menéndez Pidal, James T.

Monroe, Joaquín Rodrigo, Edwin Seroussi, Almon Shiloah, Joseph H.

Silverman, Samuel Miklos Stern, Susana Weich-Shahak, David Wulstan,

Henrietta Yurchenco, Rodrigo de Zayas, to mention just some of the

scholars, our journey through the history of Sephardic song, which is

meant to be a creative reinvention based on the numerous source studies

which have been undertaken over the past hundred years, would not have

been possible. Our special thanks go to Dr. Eckhard Neubauer.

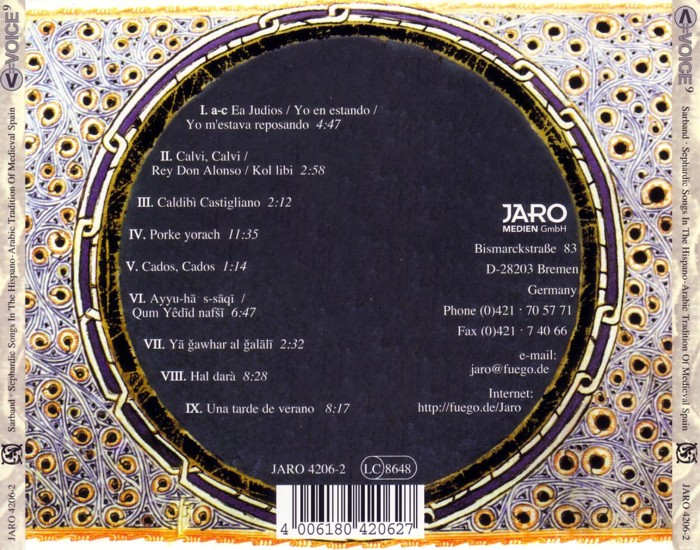

1. [4:53]

a. Ea Judios — Spain

b. Yo en estando — Morocco, Tetuan

c. Yo m'estava reposando — Juan del ENCINA (1468-1529), Cancionero musical de Palacio 77

Both

songs tell the story of a young man who cannot sleep for his desire of a

woman who is married to an old man. The historical Spanish version in

the "Cancionero musical de Palacio", set to music by Juan del Encina,

contains only the first four lines of the account, while in the

Sephardic version from Morocco the entire story has been preserved. The

two versions are basically different in melody and structure, but

exhibit several corresponding melodic elements.

2. Calvi, Calvi / Rey Don Alonso / Kol libi [3:03]

Spain, 14th century

In the 10th century, the lyric-musical genre known as muwashshaḥa became increasingly popular among Arabs, Christians and Jews alike. The last verse (kharja)

was generally written in Spanish or Hispano-Arabic. The short text

fragment "Calvi vi Calvi," mentioned by the Archbishop of Hita, Juan

Ruiz, in his "Libro de buen amor" in the 14th century, and recorded by

Francisco de Salinas as incipit in his "De musica libri septem"

(Salamanca 1577), is most likely a verse of this kind, a so-called kharja, In Arabic spelling,

"Calvi vi calvi calvi aravi" becomes: "Qalbī bi-qalbī qalbī ’arabī".

An

increasing number of Muslims were forced to convert under Christian

supremacy. Many of these moriscos met secretly in the dark hours of the

night to sing songs and dance. These nighttime meetings were called zambra/zamr or leila

(night). In the 16th century a text sung during the zambras appears in

Luis Vélez de Gómara's comedy "La hermosura de Raquel": The dance of the

moriscos, a crude parody.

The kharja "Calvi vi Calvi,"

concerned with the secretly kept "Arabic heart," might have been sung on

these occasions. in the Hebrew print "Baqaßoth" (Constantinople,

ca.1525) the melody appears as a contrafact with a Hebrew text, adopting

the "heart" from the Arabic text and imitating the Arabic phonetically:

'Kol libi, kol libi, kol libi le-avi'.

Beginning in the 16th century, the melody was frequently quoted as Baile del Rey Don Alfonso in Spanish plays;

even today it is sung in Spain as a folk song: 'Rey don Alonso, Rey mi Señor'

3. Caldibì Castigliano [2:15]

Joan Ambrosio DALZA. "Intabulatura de Lauto, Libro Quarto," Venice 1508

The

Venetian lutenist J. A. Dalza used the "Calvi, Calvi" melody as a

treble tenor for the variation which preludes his collection

"Intabulatura de Lauto."

4. Porke yorach [11:37]

Morocco, Turkey, Bosnia, Greece

The

Sephardim also sing the religious song "Odekha Ki Anitani" to the

melody of this romance. The text brings together the threads of four

different stories, known at least since the late Middle Ages. Only two

of them appear in the most widely known version of the song:

– The

Conde de Irlos leaves his young wife to seek adventure in the New World.

If he does not return within seven years, his wife can marry any man

whom her husband's clothing fits.

– The mother curses the ship on which her son leaves her.

5. Cados, Cados [1:19]

Chansonnier Sevilla (F-Pn nouv. acq. fr. 4379), late 15th century

The

three-part motet "Cades, cados" contains conglomerate of Arabic, Latin,

Greek, Hebrew and pseudo-Hebrew words. Elements of the hymn "Alma

Redemptoris Mater" as well as motifs from Hebrew piyuttim can be heard in the melody.

A

similar text is part of the medieval Easter pageant of Innsbruck (1330)

in which the Jews are crudely parodied: "Tunc Judae cantant Judaicum

... Chodus, chodus adonay, sabados sissim sossim ... chochum yochum ..."

6. Ayyu-hā s-sāqī / Qum Yêdīd nafsī [6:49]

Lyrics:

· Abū Bakr ibn Zuhr al-Ḥafīd (1113-1198): Arabic muwashshaḥa

· Don Todros ben Yehudah ha-Levi Abū'l-’Afia (1247-ca. 1306): Hebrew kharja

Music: traditional

Both

Arabic and Jewish poets used the lyrical and musical muwashshaḥa form

extremely popular in medieval Spain. The poet Don Todros was one of the

most well-known artists and scholars at the court of Alfonso the Wise

(1252-84): he was el rab de la corte.

7. Yā ğawhar al-ğalālī [2:34]

Lyrics: Ibn Quzmān (c.1086-1160)

Music: Cantiga de Santa Maria 47, late 13th century

The

tall, blond Ibn Quzman was descended from an old Arabic family of noble

lineage. In his often cynical, often erotic poetry, he combined

classical Arabic (gharib) with the local Andalusian dialect as well as Spanish expressions.

8. Hal darà [8:30]

Lyrics: Ibn Sahl (-1251)

Music: traditional

Ibn

Sahl, a Jew converted to Islam, was a legendary poet and musician in

Almohadian Seville. He was one of the last masters of the muwashshaḥa.

Ibn Sahl drowned in the River Guadalquivir: "... and the pearl returned

to its origins."

9. Una tarde de verano [8:20]

Morocco, Fez – Spain

The

story of this romance is based on the German epic poem "Kudrun" from

the early 13th century. This song was probably transported from the

Arabian Peninsula to Spain during the crusades. It tells of the rescue

of Kudrun by her brother Ortwin and Prince Herwig, following thirteen

years of humiliating captivity. Numerous forms of the story are

contained in the oral traditions of Spain, Morocco, Greece and Turkey

(including "Don Bueso y su hermana" / Don Bueso and his sister). The

octosyllabic version selected for this recording is probably more

recent, presumably "re-imported" to Spain from Morocco by way of

Andalusia.

The

Sepharad sphere of influence was initially only embodied in the word of

the Bible. Its geographical location was as yet undefined when Genesis

pointed the way and the Israelites left the land of their fathers. Over

the centuries, the term "Sepharad" gained in cultural, religious and

historical significance. Since then, in addition to a place of exile,

"Sepharad" has held a promise of a religious conviction and of cultural

self-determination.

Over two thousand years ago the Jews fled

from Nebuchadnezzar and the ruins of the Jewish empire and gradually

crossed the Mediterranean. Since Roman times there has been evidence of

Sephardic Jews in the Iberian peninsula. In the year 589 Christianity

was declared the official state religion by the ruling Westem Goths.

Exercising repression in the form of forced baptism and death threats,

these new Christians forced thousands of Jews to leave the Iberian

peninsula. As a result, those Jews who remained behind viewed the

Islamic conquest of Spain in the year 711 more as a liberation than a

threat. In the Muslim state order Jews had the opportunity to rise to

high positions in the government and administration. The Jewish

communities in medieval Spain were therefore strongly linked with the

Muslim emirates and especially with the caliphate of Cordoba. The

Hispano-Arabic Middle Ages represent an important chapter of Judaic

history. Having participated in the golden age of classical Arab culture

in the Near East, Jews played an important role in Spain as mediators

between Arab and Christian culture, and Jewish poetry and music

consequently reached a new pinnacle. In the 13th and 14th centuries Jews

were also musicians at the Castilian court. Along with Arab musicians

they played an important role in the performance of the "Cantigas de

Santa Maria" (eleven of which tell of Jewish life and culture in Spain),

compiled by King Alfonso el Sabio (1252-84). At the court of Sancho IV,

along with thirteen Christian and fifteen Arab musicians, the Jew

Ismaël played the rota and accompanied his wife when she danced.

The

14th century[sic], when the Catholic reconquest of Spain made

considerable progress, brought the harmonious co-habitation of Spanish

Christians, Jews and Muslims to an end. The pogroms and persecutions of

1391 led to mass conversions of Jews and Muslims. The mid-15th century

saw the establishment of the Inquisition, which accused many conversos

(those who had converted from other religions) of practicing their original beliefs in secret

The

exodus of Hispanic Jews began on August 2, 1492. In the course of just a

few months it is believed that over 160,000 Jews were forced by the

Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella to leave Spain and all Spanish

sovereign territories in a most undignified manner. Many Sephardic Jews

fled to French Provence. Hispanic Jews who had converted to Christianity

also settled as late as the 17th century in Bordeaux, Marseilles and

Bayonne, after they too had been forced to leave Spain and Portugal.

Many Sephardim sought to start a new life on the North African coast.

The majority however, 60,000 or more in number, found a haven in the

sovereign territories of the Ottoman Empire: in Constantinople,

Thessaloniki, Smyrna, Adrianople (Edirne), Gallipoli, Ankara, in Egypt,

Syria, Palestine and the Balkan states. As Sultan Bayezit remarked on

the exodus of the Sephardim: "It is said that King Ferdinand, King of

Castille and Aragon, is a clever man, but by driving the Jews from his

own country, he is impoverishing his empire and enriching mine."

Sephardic communities were also established in Italy (Ferrara, Livorno),

after the end of Spanish role in the Netherlands (Amsterdam), in

Germany, Austria and the New World.

Sephardic music: stories and histories

In

the Diaspora Hispanic Jews handed down their medieval Spanish past:

customs, music and language. The traditional songs characteristic of the

Sephardic Jews were and still are to this day the romanzas in the Jewish-Spanish tongue — judezmo — which is today sometimes misinterpreted as ladino (a term which actually refers to translations from Hebrew into Spanish: ladinar) and corresponds to djudiyo in the Levante and baketiya

in the Maghreb. The lyrics of these songs recount the lives of Spanish

Jewry and tell of Spanish history. Only a few written examples of this

music have survived from the Spanish Middle Ages. However, in addition

to the descriptions of Sephardic musical practice taken from medieval

sources, the Sephardim's oral heritage provides a guide to this

immensely rich musical culture.

The development of Sephardic

music is inexorably linked to the history of Spanish Jews following

their expulsion. After leaving Spain and Portugal the Sephardim settled

in numerous communities in the Mediterranean region. There they sang

their songs brought from Spain and sought to maintain their Spanish

culture. In the new environment, usually far from Spanish influence,

they lived in crowded communities, defiantly continuing to speak their

Spanish mother tongue and glorifying their Spanish past.

Since

the repertoire of songs was and to some extent still is a significant

element of Sephardic community life, it was possible to preserve those

songs over five centuries. This living tradition, in which the exiles

handed down old Spanish epic stories in late medieval Castilian, was

greatly influenced by the various languages and musical cultures of the

countries in which the Sephardim lived. The Sephardic way of life

gradually blended with local traditions in their host countries. As

early as the Middle Ages Spanish Jews had worked closely with musicians

from other cultures, and this tradition was continued without

interruption after the exodus. Not only were melodies integrated into

the performance of sacred and secular poetry, but many musical elements

too, such as the modal system, rhythmic and metric characteristics,

melodic embellishments and cadential formulas, all flowed into the

traditional repertoire. In addition, numerous new songs developed which

make up the main body of the repertoire still sung today. By the

beginning of the 18th century at the latest, the Sephardic colonies of

the western and eastern Mediterranean (Ottoman Empire) formed two

clearly distinguishable and independent cultures. Due to its

geographical proximity, the western or North African was able to

maintain its ties to the Iberian peninsula, while the eastern camp was

exposed to new influences to a great extent.

It is therefore

possible to define two main traditions within the Sephardic song

culture, with regard to repertoire, melodic structures and performance

practice: that of the eastern Mediterranean, mostly under Turkish and

Balkan (generally Ottoman) influence and that of the western

Mediterranean, significantly influenced by Moroccan and Spanish

elements. With Europe's increasing political and economic impact on the

Middle East due to colonization, western musical influences increased,

especially in Northern Africa.

Any formal comparison of songs

from the western and eastern repertoires, that is, from two independent

music traditions which enjoyed only a minimum of mutual contact, reveals

the fact that, quite independently of one another, both traditions have

handed down some of the repertoire and characteristics of the medieval

Sephardic romance heritage of Spain.

Some Sephardic Jews

continued their emigration from Thessaloniki and Constantinople, the two

central colonies in the Ottoman Empire, to Jerusalem, where an

important Sephardic community developed which even today is still an

amalgam of Palestinian, Turkish and Balkan elements. This accounts for

the many corresponding features in the lyrics and tunes of Palestinian

and Balkan songs. The female voice is dominant in traditional Sephardic

musical performance. Many of the topics featured in the songs are

represented from a woman's point of view, since it was the women who, in

the Diaspora, passed on the Sephardic traditions to their daughters.

Today the singers further develop the living tradition, accompanying

themselves on the frame drum (pandeiro). The Spanish monk Andrés

Bernáldez was an observer of the Jews' expulsion from Spain and left the

following lines, documenting the important role of women in the

Sephardic song tradition: "They left the country in which they were

born. Great and small, young and old, on foot, donkeys or in carts, each

followed the path to his or her chosen destination. Some stopped at the

wayside, some collapsed from exhaustion, others were ill, yet others

dying. No fellow creature could have failed to have pity on these

unhappy people. All along the way there were constant appeals for them

to accept baptism, but their rabbis instructed them to refuse and

implored the women to sing, beat their drums and to uplift their souls."

Later, in the Diaspora, the Sephardic romances were adapted by

professional male musicians and performed in coffee houses and taverns.

In the same way, sacred texts were — and still are — set to romance

melodies.

The Romance

As

early as the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the romance or

ballad was a very popular song-form in Spain. It originally survived as

folk song and was not introduced to the Spanish court until near the end

of the 15th century. Like most Sephardic romances, especially those

handed down through the eastern tradition, the 15th century romance, as

notated in various sources including the "Cancionero musical de Palacio"

and in the tablatures of 16th century vihuelists (there it described as

a romance viejo), has a poetic structure of sixteen syllables

with assonant rhymes and a musical form with four phrases of equal

length. The first musical phrase often has an arched, rising and then

descending melodic contour; sometimes we encounter a purely ascending

melodic line. The second melodic phrase is usually higher and touches

the melodic high point. These two melodic lines are seldom identical.

The third melodic section then descends stepwise to the lower cadence

note. The fourth phrase often ends the melody in a cadential downward

movement.

Many of the melodies are based on a descending chromatic tetrachord which is also characteristic of the musiqà andalusiyya. In the eastern Mediterranean region melodies can often be attributed to the modes (makamât)

of Islamic musical culture; the Hüsseynî, Ushâk, Bayâti, Hicâz,

Hicâzkâr, Pûselik, Nihâvent and Ferahfeza modes are frequently

encountered. In the western Mediterranean, especially in Morocco, the

diatonic principle was often applied to the melodies, probably under

later European influence, and they were made to conform with major/minor

key tonality.

In the rhythmic-metric performance of the

romances, metric and non-metric sections are often interwoven. The

eastern tradition reveals a strong tendency towards a performance devoid

of metric constraints, while in the western/Moroccan repertoire the

abrupt shift from the binary to the ternary meter is popular.

The

Judaic musical culture attained great significance through its

preservation and dynamic modification of medieval Spanish romances on

the one hand, and of the Arabic-Andalusian muwashshaḥat and kharjas

on the other. This is demonstrated in the second section of our journey

through time and cultures by means of the different compositional

genres. It is our aim to create a living aural picture of the former

symbiosis of medieval story-telling of northern Spanish, Andalusian or

Hispanic-Jewish origin with oriental melodies from Asia Minor or the

Balkans: the sphere of influence of "Sepharad."

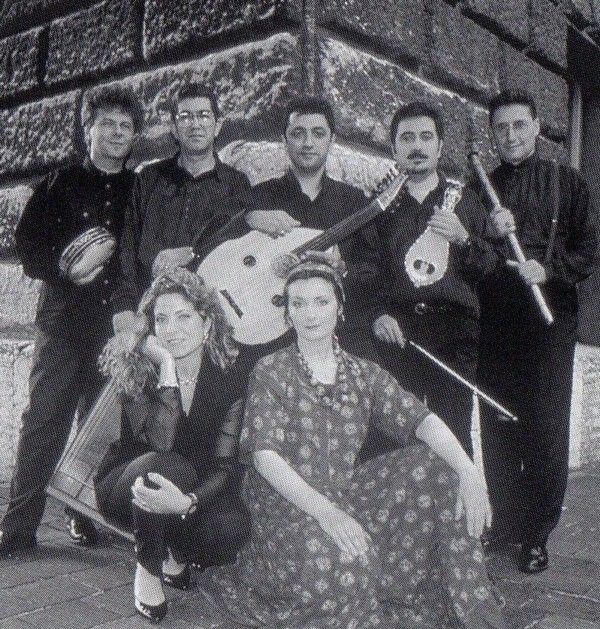

SARBAND

Vladimir Ivanoff

Fadia El-Hage (Lebanon): Voice

Belinda Sykes (Great Britain): Voice, Shawms, Bagpipes

Mustafa Doğan Dikmen (Turkey): Ney (flute), Kudüm (kettle drums), Voice

Ahmed Kadri Rizeli (Turkey): Kemenge (fiddle), Percussion

Ihsan Mehmet Özer (Turkey): Kanun (psaltery)

Mehmet Cemal Yesşilçay (Germany, Turkey): Ud (lute), Cura (longnecked lute), Percussion

Vladimir Ivanoff (Germany, Bulgaria): Percussion, Ud, Renaissance lute

with guest

Axel Weidenfeld: Renaissance lute (track 3)

The

name Sarband stems from Persian and Arabic, and denotes the improvised

joining of two parts of a musical suite. Vladimir Ivanoff founded the

ensemble Sarband in 1986 and has been pursuing an archaeology of complex

connections ever since. Above all, Sarband endeavors to point out

possible links between European music and the Islamic and Jewish musical

cultures. With sensitivity and intensity, Sarband celebrates the

symbiosis of Orient and Occident. The continuous musical collaboration

among the members of the ensemble ensures that a dialogue on equal terms

is maintained. It is the exchange of practical musical experience

between musicians from different cultures that make the performances of

Sarband fascinating, lively and extremely authentic.

In their

performance of European and Oriental medieval music, the Turkish,

Italian, English, Bulgarian, Arab and German musicians participating in

this project draw upon the colorful palette of instruments, vocal and

instrumental techniques and the art of improvisation which are still to

be found in Islamic culture today. Sarband's unique repertoire has won

them wide acclaim internationally. Over the past few years Sarband has

performed at numerous international festivals of varying orientations

ranging from Early Music to Avant-garde.

Sarband's musicians do

not regard their work as something sporadic but as an expression of

being and life. Just as religious, economic, cultural and political

differences between the Orient and the Occident play a predominant role

in today's society, Sarband's work endeavors to show that music has

always served as a medium of reciprocal respect, and can continue to do

so today: a model for peace.

Fadia El-Hage (born in 1962

in Beirut) started her professional performing career as a pupil, with

the orchestra of the brothers Rahbani. From 1978-79 she performed as a

singer and actor in several TV productions in Lebanon and Jordan. From

1980-81 she performed as a soloist in two Lebanese opera productions.

From 1978-81 she produced several recordings of traditional Lebanese

music. From 1980-84 she studied psychology at the Lebanese University.

From 1985-90 she studied voice with Professor Felix Rolke at the

Richard-Strauß conservatory in Munich with further studies in opera from

1990-92. Since 1989 she has performed as a soloist with Sarband and Vox

in international concerts and CD productions. She lives with her family

in Beirut and teaches at the Lebanese University.

Belinda Sykes

(born in 1966) studied voice with Bulgarian folk singers, going on to

collect songs from Bulgaria, Morocco, Spain, Hungary and India. As an

instrumentalist, she studied oboe and recorder at the Guildhall School

of Music, and won the 1990 Reichenberg award for Baroque Oboe. She has

performed with The New London Consort, Red Byrd, Tragicomedia, The Harp

Consort, The King's Consort, The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightment,

The English Consort, L'Orient Imaginaire and Sarband. She teaches at the

Guildhall School of Music, Exeter University and the Welch College of

Music, and has given workshops at the Birmingham Conservatory, Royal

Academy of Music and Bremen Academy of Early Music.

Mustafa Doğan Dikmen

was born in Ankara in 1958. Between 1975 and 1978 he played the kudum

for Ankara State Radio and from 1979-83 studied at the Istanbul

Conservatory. In 1992 he became a soloist for TRT Istanbul. With

Professor Alaeddin Yavasça and Professor Kani Karaca he has worked on

Ottoman art music and now teaches at various schools of music in Turkey.

He is a member of the groups Ferahfeza, Emre, L'Orient Imaginaire and

Sarband.

Ahmed Kadri Rizeli was born in Istanbul in 1959. He was

still at school when he first learned to play the violin. He later

studied Turkish art milsic with Sadi Hosses and the theory of music and

the kanun with Necdet Varol. He has been a soloist with TRT since 1981.

Between 1981 and 1983 he was also a soloist with the Istanbul University

Ensemble. He is a member of the groups Ferahfeza, Emre, L'Orient

Imaginaire and Sarband and works as a record producer for Turkish art

music.

Ihsan Mehmet Özer was born in Istanbul in 1961.

From 1978-82 he studied at Istanbul Conservatory and with Ruhi Ayangil.

He has performed with Demirhan Altug, Tülün Korman, Metin Örser, Ergen

Korkmaz and Haydar Sanal. He is a soloist with TRT Istanbul, and the

orchestras of Istanbul University and the Turkish Ministry of Culture.

In recent years he has also become known as a composer of modern and

traditional Turkish art music. He performs as a soloist with the Ahmet

Özhan group for historical Turkish music and is a member of the groups

Ferahfeza, Emre, L'Orient Imaginaire and Sarband.

Mehmet Cemal Yeşilçay

was born in Istanbul in 1959. From 1976-1982 he studied Islamic music

with Seyyid Nusreddin Yesilcay in Istanbul. From 1980-85 he studied the

ud and composition with CinuSen Tanrikorur in Ankara. In 1985 he founded

the groups Sadaraban and Ferahfeza, with which he performs in Turkey

and abroad. He also works as a composer of contemporary and traditional

Turkish art music. His works have been performed at the Munich Biennale.

He is the musical director of the ensemble Emre, a founding member of

Sarband and a member of L'Orient Imaginaire.

Musical direction: Vladimir Ivanoff

Recording: Jochen Scheffter & Vladimir Ivanoff, Beirut / Istanbul / Munchen, 1994

Post production: Friedrich Thein & Vladimir Ivanoff, Bremen 1994

Producer: Vladimir Ivanoff Executive producer: Ulrich Balß

Translations: Judith Rosenthal: English - Vladimir Ivanoff: Deutsch - Shlomo Israeli: Hebrew

Cover picture adapted from: Jerusalem, centre of the world

Worldmap by Heinrich Bunting. 1585.

Coverdcsign by Rank

[DORIAN: Catalog No. DOR-93190

Booklet Copyeditor: Katherine A. Dory

Graphic Design: Kimberly Smith Co.

Cover: Jewish Musicians at Mogador, Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), Louvre, Paris, France

Courtesy of Giraudon/Art Resource NY (501142899)]

Thanks