medieval.org

sequentia.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (EMI) 1C 067-99 921 T (LP)

1981

CD, 1988 — Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (EMI) CDC 7 49704 2

medieval.org

sequentia.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (EMI) 1C 067-99 921 T (LP)

1981

CD, 1988 — Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (EMI) CDC 7 49704 2

1. Olim sudor Herculis [10:08]

Firenze, Bibl. Laur., Plut. 29.1, fol. 417

Sänger, Sängerin, Gittern, Fidel |

2 voices, gittern, fiddle

2. Lai du Kievrefuel [11:53]

Paris, Bibl. Nat., fr. 12615, fol. 66

Sängerin, Fidel |

voice, fiddle

3. Lai Markiol [6:39]

Paris, Bibl. Nat., fr. 12615, fol. 72

Fidel, Harfe |

fiddle, harp

4. Lai des Amans [14:29]

Paris, Bibl. Nat., fr. 12615, fol. 69

Sängerin, Fidel, Harfe, Laute |

voice, fiddle, harp, lute

5. Samson dux Fortissime [14:27]

London, Brit. Mus., Harley 978, fol. 1

Sänger, Sängerin, Fidel, Gittern |

2 voices, fiddle, gittern

SEQUENTIA, Ensemble für Musik des

Mittelalters

Ensemble for Medieval Music

Barbara Thornton — Gesang | voice

Benjamin Bagby — Gesang , Harfe | voice, harp

Margriet Tindemans — Fidel | fiddle

Crawford Young — Laute, Gittern | luth, gittern

Instrumentarium:

5saitige Fidel von / 5-string fiddle by Fabrizio Reginato (Fonte Alto, Italien / Italy ) 1978

Bogen von / Bow by D.R. Miller (Boston, USA) 1980

15saitige Harfe von / 15-string harp by Alan Crumpler (Leominster, England) 1979

4chörige Gittern von / 4-course gittern by Fabrizio Reginato (Fonte Alto, Italien / Italy ) 1973

4chörige Laute von / 4-course lute D.R. Miller (Boston, USA) 1980

4saitige Gittern von / 4-string gittern by Guy Biechele (Boston, USA) 1979

Aufgenommen / Recorded : Cedernsaal, Schloß Kirchheim

Dr. Thomas Gallia • Klaus L Neumann Paul Dery

Technik / Techinical equipment : harmonia mundi acustica

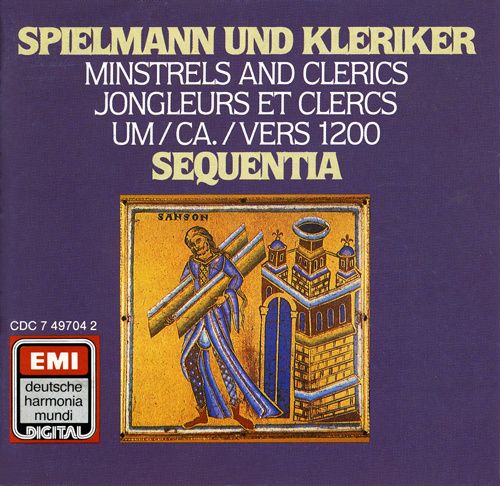

Titelbild: Samson trägt die Tore von Gaza (emaillierte Schmuckplatte, 12. Jh. Mosan)

Front cover: Samson carries the gates of Gaza (enamelled decoration plate, 12th century, Mosan)

Mit freundlicher Genehmigung von / By kind permission of The Trustees of the British Museum

Gestaltung Vorderseite / Front cover design: B & M Wiesinger

EMI Records Ltd.

Eine Co-Produktion mit dem Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln WDR

CD: ℗ 1981 harmonia mundi / © harmonia mundi, 1988

Recorded June 1980 in the Zedernsaal of Schloß Kirchheim (D).

Released 1981 as LP by Deutsche Harmonia Mundi in coproduction with WDR Köln

and 1988 as digitally remastered CD by EMI (CDC7497042). —

sequentia.org

MINSTRELS AND CLERICS c. 1200

Breton Lai · Latin Heroic Lai · Sequence

The title of this recording focuses on an important underlying aspect

of medieval, and especially 12th-century, musical life: the interaction

between two seemingly opposed groups of musicians, the clerics of the

church and the professional secular minstrels. The conventional modern

view of music in medieval Europe often makes a simplistic distinction

between, on the one hand, the secular world of the travelling minstrel,

who sang of erotic love and politics before noble audiences in castle

halls, accompanied by a wide variety of instruments, and, on the other

hand, the hermetically sealed world of church music, where priests,

monks and nuns devoted themselves to a ritual music of praise and

devotion, looking upon minstrels, love songs and musical instruments as

works of the devil.

In fact, these two worlds had much in common. The courtly minstrel (Old

French, jogelor; Middle High German, Spîlman) and

the clerical musician (Latin: clericus, referring to all

clergy, with the term cantores applying to liturgical vocal

soloists) shared not only a love of music and poetry, but a vast

repertoire of melodies, song-forms, instruments, and instrumental/vocal

techniques as well.

But how and where did these worlds intersect? As with any investigation

of medieval life, we must piece together the whole picture from

tantalizing bits of evidence. For instance, we know that in the

12th-century, monasteries were recruiting increasingly among young

adults of noble birth, as opposed to the earlier custom of accepting

young children as oblates. This means that many novices,

especially those of noble birth, would have come into the cloister with

a prior experience of tournaments, courtly entertainment, secular love

poetry and music. In addition, we know that several of the Occitan

troubadours spent the winter months in monasteries, composing new cansos

of love; and from these same monasteries, especially those in

Aquitaine, came the 12th-century flowering of monophonic and polyphonic

versus, masterpieces of the cantores' art. We even find

secular musicians employed by members of the Church hierarchy, those

bishops and abbots of noble birth whose tastes in music, as well as in

politics, were more worldly than we might think. Medieval English

payrolls inform us, for instance, that certain bishops and abbots had

their own private minstrels. The Bishop of Durham once attended a royal

festivity in the company of his two "harpours". Finally, we find an

entire repertoire of simple clerical songs from the so-called

Notre-Dame School of the late 12th century, which were probably

intended for group singing, playing, and even dancing on special

feast-days.

The list of such examples could go on and on. As we examine the

"Renaissance of the 12th-Century", there begins to emerge a picture of

great flux and exchange between the musical spheres of court and

church. For this recording, we have chosen larger lyric forms, common

in northern Europe, such as the sequence and the lai, forms

which served the singer of courtly love, the instrumentalist, as well

as the cantores of the church.

The Music

Olim sudor Herculis

This classical sequence, with its anti-love text, originates from the

court of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, overlords of the vast

12th-century Angevin Empire. It is likely that such a piece would have

been known in a clerical milieu as well. There are some indications

that the refrain, which is not normally an element of a sequence, can

be sung after each half-stanza. Our performance recreates the piece as

it would have been enjoyed by musical and literary cognoscenti,

both courtly and clerical, during an evening's entertainment.

Reflecting contemporary musical practice in the church, some sections

are sung in free rhythm over a sustained tone, while others are

strictly rhythmic, and follow the rules of discantus, or

improvised counterpoint. The well-known refrain melody is sung and

played by all those present, with each musician helping to create a

polyphonic elaboration of the melody.

Lai du Kievrefuel

Lai Markiol

Lai des Amans

Marie de France, a noblewoman who probably lived at the court of Henry

II and Eleanor of Aquitaine in the late 12th-century, relates how she

came into contact with Breton lais, those exotic love-stories

which were sung and played by Breton minstrels visiting the court.

These lais, which are lost to us today save in Marie's French verse

translations, have evocative titles such as "Equitan", "Les deus

amanz", "Eliduc", and "Chevrefoil". From contemporary sources, we know

that Breton lais were an important form of courtly

entertainment. Even that paragon of courtliness, Tristan, knew them

well, as he tells his Isolde: "Bons lais de harpe vus apris / lais

bretuns de vostre pais ..." ("I have taught you good lais to the harp,

Breton lais of your own country..."). Unfortunately for posterity, the

melodies to these Breton lais were passed orally from musician

to musician, and probably never written down. The pieces recorded here

are written lais which have similar titles to the pieces Marie

describes, but whose sophisticated love texts are not specifically

Breton. These anonymous lais, with curious titles —

"Kievrefuel" ("honeysuckle"), "Markiol" and "des Amans" — are

composed of repeating melodic cells of various lengths, corresponding

to the complex poetic structure of the text. The melodies were possibly

never "composed" in the modern sense of the word, but rather came from

an oral tradition, which, if not specifically that of Marie's Breton

harpers, was certainly influenced by the strong imprint they left on

northern European musical culture.

For this recording, we have taken three lais from the same manuscript

collection, and given each of them a different mode of performance.

First, in the "Lai du Kievrefuel", we hear an intimate rendering, in

which the singer and the instrumentalist work together carefully to

emphasize and clarify the structure of this lai which is "sweeter than

honey". The combination of the voice and one instrument was a favoured

manner of performance in the 12th-century. The second lai, "Markiol",

is given a purely instrumental rendering, a practice known as playing

the note ("note" or "melody") of the lai. That this was

commonly done is illustrated in many contemporary sources, such as the Roman

de Flamenca:

L'uns viola lais de Cabrefoil,

E l'autre cel de Tintagoil;

L'us cantet cel dels Fins Amanz,

E l'autre cel que fes Ivans.

L'us menet arpa, l'autra viula;

L'us flütella, l'autre siula;

L'us mena giga, l'autre rota;

L'us diz los motz e l'autrels nota

(One fiddled the lai of Kievrefuel,

and the other that of Tintagel;

one sang that of Fins Amanz,

and the other the lai that Ywain made.

One played a harp, the other a fiddle,

one played a flute, the other a whistle;

one had a giga [a type of fiddle], the other a rota;

one delivered the words, and the other the melody...)

The "Lai des Amans" is given a performance such as one would hear at a

courtly celebration, wedding or knighting ceremony, when many minstrels

had gathered. The four musicians, each of whom knows the lai,

come together on this occasion for a festive rendering — a real

"performance".

Samson dux fortissime

The story of the Old Testament hero Samson (Judges 14-16) is

dramatically told in this composition, which has a lai

structure. Here, as in the Breton lais, repeating melodic cells

in various combinations build up to form a large musical structure.

Although the exact provenance of the piece is not clear, it probably

came from a clerical milieu, where it would have served as ennobling

entertainment. For our performance, we have assumed a formal

surrounding, such as a bishop's palace, where the bishop's personal

minstrels join with clerical musicians versed in discantus singing. As

a prelude and postlude to the dramatized performance, the instruments

play a polyphonic composition found in the same manuscript as the lai

itself.

© Benjamin Bagby, 1981

The Texts

The two Latin compositions

The twelfth century saw new heights of achievement in two cognate

poetic-musical forms that are first attested in manuscripts of the

ninth century: the lyrical lai and the sequence. From the

earliest times, both forms were used for vernacular as well as Latin

compositions, for profane as well as sacred themes. Where the classical

sequence was composed basically in symmetrical pairs of half-strophes,

sung to the same melody, with a new melody for each new pair, the

lyrical lai could employ both more complex and freer strophic

groupings.

Our evidence about the performance of the (lost) Breton lyrical lais

strongly suggests that their poetic and musical form was closely

similar to that of their Latin counterparts. The Latin lai, not

widely attested between the ninth century and the twelfth, emerges

again as a high art form in the cycle of laments (planctus)

composed in the 1130s by Peter Abelard (1079-1142). Abelard, a Breton

by birth, will have absorbed the melodies of vernacular Breton lais

during his youth and been inspired by them (even though he was not

himself Breton-speaking).

Samson dux fortissime

One of the laments in Abelard's cycle is that of Israel over the death

of Samson. This piece will have been known to the anonymous author of Samson

dux fortissime, who planned his composition almost, we might say,

as a riposte to Abelard's. Where in Abelard the chorus was the Jewish

people, who could see in Samson's death only a tragic waste, a suicide

bred of despair, the close of the new piece (composed perhaps in

northern France in the later twelfth century) shows the chorus, or

commentator on the events, proclaiming Samson's death a victory and a

glory. Implicit here is the Christian figural interpretation, by which

Samson, suffering and dying and delivering his people, foreshadows

Christ.

The text survives in three manuscripts of the thirteenth century, one

Anglo-Norman and two German. It is corrupt in all of these, but the

Anglo-Norman one, which contains the melody as here performed, can be

corrected with the help of the other two. One of the German manuscripts

makes clear by a rubric that the piece was dramatic in intention: it

indicates that Dalila must sing the words ascribed to her. Yet the

drama is far from naturalistic: the poet uses an astonishing freedom of

time-sequence. Dalila enters and recedes each time as if she were a

phantom, an intense projection of Samson's own memories: musically it

is noteworthy, for instance, that her melody of victory (in st. 14)

echoes note for note his melody of defeat (in st. 12). Near the close,

too, as Samson describes his act of vengeance, naturalistic time is

suspended, so that he is able to tell his victory as if he had survived

it (which the Bible explicitly denies).

Olim sudor Herculis

This song, a classical sequence with refrain, is a virtuoso composition

in its strophic forms, rhymes and word-play. It alludes lightly to the

ancient myth of the twelve labours of Hercules, and laughingly

contrasts his fortitude in these with his susceptibility in love. The

author, Peter of Blois (ca. 1135 —1212), had a cosmopolitan

career as courtier and scholar, and became secretary to Henry II of

England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. In recent scholarship, Peter has come

to be recognized as one of the leading twelfth-century lyrical

composers. In a study of his poetry (in the journal Medieval Studies,

1976), I argued for a canon of some fifty lyrics that are probably by

Peter, and many of these survive with their melodies. Some, such as Olim

sudor Herculis, will have been performed not only at Henry and

Eleanor's court but also (as the occurrence of this song in one of the

major manuscripts from Notre Dame of Paris shows) as entertainment in

the scholastic world, in the more sophisticated cathedral schools. The

theme of this sequence is characteristic of Peter's lyrics: again and

again he writes witty, playful palinodes, claiming that he has rejected

— or is just about to reject — the lures of sensual love,

or of courtly frivolities, that he has turned over a new leaf. Yet the

claim is never made decisively: Peter loves repenting — and

gazing back at what he is repenting of.

Here he resolves to abandon love, and asks his fictive beloved,

Lycoris, to do so too: yet not because God is displeased by a sensual

way of life, but for a worldly reason: 'Love deflowers fame's merit',

and Peter wants to become famous. He is amazed that Hercules (whose

name was often at this time thought to mean 'fame of heroes') was so

weak, allowing his heroic reputation to be tarnished; yet between the

lines Peter slyly hints that for Hercules it was worth it to give up

all for love. And when he ends, 'I'm stronger than Hercules, for look,

I'm running away!' the note of irony and self-mockery is unmistakable.

© Peter Dronke, 1981

Breton lais

The lai of Chevrefoil ("honeysuckle") is the title of one of

the Breton lais set by Marie de France, which recounts an

episode from the Tristan and Isolde legend: a branch of honeysuckle was

used as a signal between the lovers in the woods where they were to

meet in secret. Marie says that in remembrance of that meeting, Tristan

composed a lai called Chevrefoil. The musical version presented

here, which shares only its title with Marie's Breton lai, is

earnest and sweet in its tone and imagery, making a lover's sentiments

believable. Likewise, Marie retells the lai of Les Deus

Amanz, based on the old legend about two noble young lovers in

ancient Normandy, whose headstrong passion leads only to their sad

deaths on a mountaintop. In the musical version, Lai des Amans,

the poem tells no story, but rather fascinates the listener with its

skilled and playful composition of rhyme, sound and sentiment,

revealing a courtly poet of inventiveness and refinement.

© Barbara Thornton, 1981