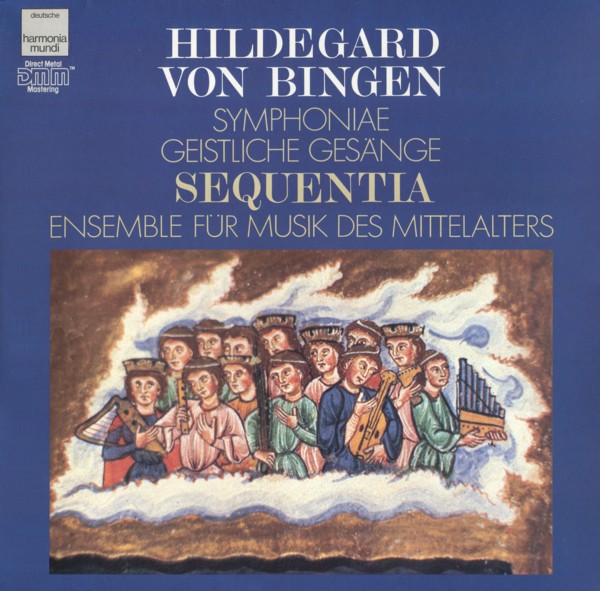

HILDEGARD von BINGEN. Gestliche Gesänge / Sequentia

Symphoniae

Symphonia harmoniae caelestium revelationum

medieval.org

grabación: 1982-1983

LPs:

1983 · Harmonia Mundi (BASF) 74321 20 198-2 [LP]

1985 · Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (EMI) 1C 067 199 976 1 [LP]

CDs:

1987 · Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (EMI) CDC 7 49251 2 [CD]

1989 · Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) "Editio Classica" 77020-2-RG [CD]

2004 · Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) "Splendeurs" 82876 60152 2 [CD]

[Seite 1]

1. O quam mirabilis [2:41]

antiphona · JF

2. O pulchrae facies [3:55]

antiphona [De Virginibus] · Vokalensemble, 2 Fideln, Harfe

3. O virga ac diadema [4:50]

sequentia [De Sancta Maria] · BTh, CS, Vokalsensemble

4. Instrumentalstück I [1:53]

2 Fideln, Flöte, Harfe

5. O clarissima mater [8:07]

responsorium [De Sancta Maria] · SS, JF, ThL, CT, Flöte

6. Instrumentalstück II [5:00]

2 Fideln, Flöte, Harfe

7. Spiritui sancto honor sit [4:56]

responsorium. [De Undecimum Milibus Virginibus] · LM, Vokalensemble, Fidel,

Psalterium, Harfe

8. O virtus sapientiae [2:53]

antiphona · Vokalensemble, Organistrum

[Seite 2]

9. O lucidissima Apostolorum turba [6:41]

responsorium [De Apostolis] · GL, Vokalensemble, 2 Fideln, Harfe,

Flöte

10. Instrumentalstück III [2:58]

Flöte, Harfe

11. O successores fortissimi leonis [2:10]

antiphona [De Confessoribus] · Vokalensemble, Fidel

12. O vos felices radices [5:07]

responsorium [De Patriarchis et Prophetis] · BTh, Vokalensemble, Symphonia

13. Instrumentalstück IV [5:19]

2 Fideln, Flöte, Harfe

14. Vos flores rosarum [5:46]

responsorium [De Martyribus] · Vokalensemble

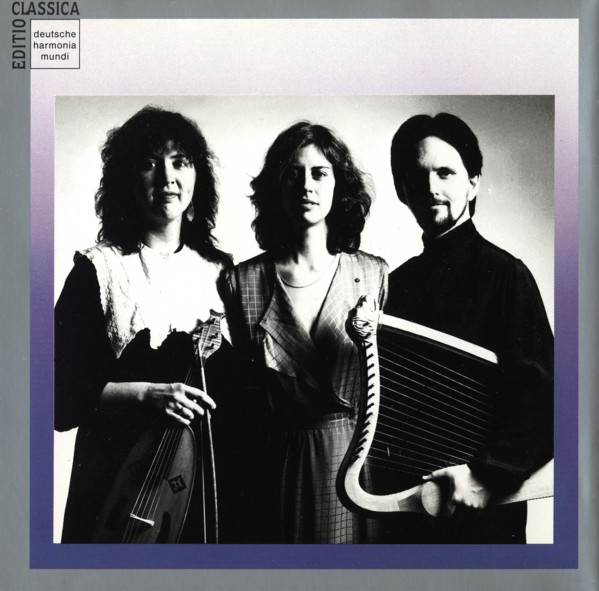

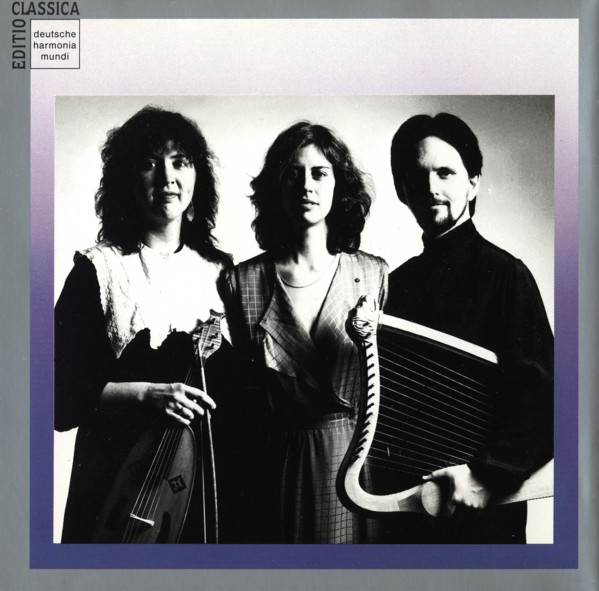

SEQUENTIA

Ensemble für Musik des Mittelalters

BTh Barbara Thornton, Gesang, Leitung des Vokalensembles

Margriet Tindemans, Fidel, Psalterium, Leitung des

Instrumentalensembles

Benjamin Bagby, Harfe, Organistrum, Symphonia

mit

Gesang:

JF Jill Feldman

GL Guillemette Laurens

ThL Theresa Lister

LM Lauri Monahan

Margaret Reines

SS Sally Sanford

CS Candace Smith

CT Caroline Trevor

Fidel: Sally Cunningham (#4, 6, 10, 13 - #7)

Flöte: David Hart (#4, 6, 10, 13), Liane Ehlich

(#9)

Bearbeitung der Instrumentalmusik von Margriet Tindemans und Benjamin Bagby

Aufgenommen:

16. —19.VI. 1982, Klosterkirche Knechtsteden

17.— 20.VI. 1983, Mandelsloh, St. Osdag

Thomas Gallia (#4-6, 10, 13) · Barbara Valentin

Produzent: Klaus L Neumann

Schnitt: Paul Dery · Barbara Valentin

Technik: Sonart, Milano (#4-6, 10, 13) · WDR: Hermann Kaldenhoff

Quellen:

Wiesbaden, Hessisches Landesbibliothek, Hs. 2 („Rupertsberger

Riesenkodex") fol. 466-473

Dendermonde (Belgien/Belgium), Klosterbibliothek Cod. 9

(„Villarenser Kodex"), fol. 156-167

SYMPHONIAE

Hildegard (born in 1098) began to compose liturgical poetry and music

in the 1140s, at the time when she first felt the courage to write down

her visions. Already in 1148 a Parisian magister, Odo,

commended the originality of her songs; in the 1150s she gathered them

into a lyrical cycle, that she called her 'Symphony of the harmony of

heavenly revelations' (Symphonia harmoniae caelestium revelationum).

This, in its first version, contained some sixty antiphons,

responsories, sequences and hymns, suited to many feasts of the

liturgical year. In the twelfth century only Peter Abelard, in the

1130s, attempted a cycle of liturgical composition on so large a scale.

Close study of the two manuscripts in which her cycle is preserved

enables us to distinguish also a later, enlarged version of the Symphonia,

where Hildegard had added some outstanding songs, including two of

those performed here: the two antiphons with more philosophical themes

— on divine foreknowledge (I) and divine Wisdom (VIII) —

probably belong to the time of Hildegard's last major work, her

cosmology Liber divinorum operum (1163-73). Lyrical invention,

that is, retained a distinctive, though gradually less prominent, place

in Hildegard's astonishingly varied and prolific writing. Symphonia

is a key concept in Hildegard's thought, and one that she discusses in

early as well as late works. It designates not only a harmony of

diverse notes produced by human voices and instruments, but also the

celestial harmony, and the harmony within a human being. The human

soul, according to Hildegard, is 'symphonic' (symphonialis), and

it is this characteristic that expresses itself both in the inner

accord of soul and body and in human music-making. Music is at the same

time earthly and heavenly — produced by earthly means, but able

to evoke for mankind, at least briefly and partially, the heavenly

consonance ('Stimmung') that they possessed fully in Paradise before

the Fall. In the words of Hildegard's younger contemporary, the

poet-theologian Alan of Lille, a symphonia implies an

exultation of the mind, to which the vocal celebration and the

instrumental execution correspond. Thus, with the consonance of mind

and voice and instruments, the symphonia becomes a 'good work'

in an existential as well as an artistic sense.

Hildegard's poetic language is among the most unusual in medieval

European lyric. She shows herself aware of the imagery of mystical love

in the Song of Songs, as well as of certain traditional figural

relationships elaborated by the Church Fathers. Thus for instance both

Ecclesia and a virgin martyr can be portrayed as the bride of the

divine Lamb; Mary is seen as the healer of Eve's guilt, or as the

flowering branch of the tree of Jesse, or as the dawn in which Christ

the Sun rises. But in developing such images and expressions Hildegard

delights in poetic freedom, and in taking diverse kinds of language to

new limits. I would signal especially her daring mixed metaphors, her

insistent use of anaphorai, superlatives and exclamations, her

intricate constructions in which several participles or genitives

depend on one another. In one of her most compressed songs (XII), the

patriarchs and prophets are the roots of a fruitful plantation whose

summit, which they foreshadow, is Christ, but Christ is at the same

time a whetstone, that is heralded by a fiery voice (John the Baptist),

and that demolishes an abyss (in the harrowing of hell). Hildegard's is

a lyrical language that sparkles with intellectual innovation while

remaining rhapsodic in its impulses. In the English translation I have

tried to reflect as far as possible the superbly obstinate

individuality of her diction. Her poetic effects are often strange or

violent, and never (as in the hymnody of most of her contemporaries)

smooth.

Peter Dronke

As abbess of Rupertsberg, Hildegard's authority and creative output

increased significantly. Between 1151-1158 Hildegard was writing and

collecting her musical compositions (as mentioned in her second vision

cycle, Liber Vitae Meritorum). They were intended for

liturgical use at the convent, and called symphoniae harmoniae

celestium revelationum, a title meant to indicate their divine

inspiration as well as the idea that music is the highest form of

praise in Creation, carrying as it does echoes of the sounds of the

heavenly spheres. We have two extant manuscripts of symphoniae,

yielding text and notated music for seventy-seven songs (as well as the

mystery play, Ordo Virtutum). (These are the Villarenser Codex

in Dendermonde, Belgium, and the Riesenkodex, Wiesbaden.) The songs are

generally praise songs to personages from the Christian pantheon of

saints, apostles, martyrs, virtues, deities, etc. Not surprisingly,

feminine figures are predominately worshipped — 15 of the songs

are addressed to the Virgin Mary, and 13 to Saint Ursula.

THE PIECES

1th SIDE

The first side of the recording reflects Hildegard's profoundly

feminine religious soul by presenting the texts and music she created

to praise those female divinities of her allegorical world — the

Virgin Maria, the virgins who inhabit heavenly realms at the end of

time, the St. Ursula, and the virtue of Wisdom, traditionally considered a type of feminine Deity.

O quam mirabilis (Antiphona)

Here is Hildegard's immensely loving depiction of life's central

miracle: creation. God breathed his breath into his creature and gazed

eternally into its face with ineffable love and knowledge.

De virginibus (Antiphona)

Hildegard sees virgins as pure beings belonging to God. Their faces,

turned eternally towards Him, reflect his luminosity.

De sancta Maria (Sequentia)

This sequence show Hildegard's unconventional use of forms, for it

scarcely resembles the classical sequence of the period. There is no

poetic meter, and the logic of the verses depends entirely upon the

enlargement of her symbolic images. It demonstrates the great

importance she attributed to the miracle of virgin birth — as

Maria had been chosen as the vessel for the birth of the Deity, she

redeemed her sex from the sin of Eva, and served as the universal

symbol of spiritual receptiveness.

Instrumental piece

Instrumental music is another means, in Hildegard's view, of praising

the Creator, "So should we, acknowledging God in the faith, praise Him

eternally in song, and in joyful sound without end. 'Praise him with

the sound of the harp', of profound submission, 'and in the sound of

the zither', that honey-flowing song. 'Praise him with string-playing',

the salvation of humankind, and 'with the sound of the flute', of

divine protection".

Scivias III, 13

O clarissima mater

This is a piece which, in text and music, evokes an image of Maria as

all that is mild, soothing and exquisite. Unlike Christ's war-like

triumph over Death, hers has been a soft one of healing. The flute

accompaniment emphasizes the smoothness and brilliance of this vision

of the Virgin.

De undecim milibus uirginibus (Responsorium)

This composition praises the passion of St. Ursula and the legendary

11,000 virgins who "gathered around her like doves", and chose to

martyr themselves as she did.

O virtus sapientiae (Antiphona)

A short antiphon for the virtue of Sapientia or Wisdom, who is

extensively praised in the Book of Proverbs. It creates a sense of the

wonderful circular motion of the singing of seraphim, mixing images of

celestial omnipresence and feminine fecundity.

2nd SIDE

The second part of the recording is dedicated to laudatory pieces which

Hildegard received in the last revelation of the Scivias cycle.

In the penultimate vision, she has witnessed the end of Time and of the

World, and the falling away of all that was mortal. The triumphant

final vision consists of nothing more than the joyful sounds of eternal

praise. The heavenly voice says to her, "As if with one soul and one

heart these songs, (heard in the vision), praise the glory of those who

are in Heaven. Their melodies carry into the heavens that which the

word makes manifest. Thus, O mankind, you must heed this song sung in

most perfect accord of the mystical words of the prophets (De

patriarchis et prophetis), the song of (Christ's) widely proclaimed

and miraculous teaching, (De apostolis), the song of the

spilling of blood of those who faithfully sacrificed themselves, (De

martyribus), and the song of priestly mysteries (De confessoribus)."

Scivias III, 13.

Barbara Thornton