English Songs of the Middle Ages / Sequentia

Englische Lieder des Mittelalters

medieval.org

sequentia.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 77019

1987

St. GODRIC · ±1170

1. Sainte Marië viërgenë – Crist & St.

Marië – St. Nicholas [4:12]

ensemble

2. The milde Lomb, isprad o rode [10:17]

The gentle Lamb — B. Thornton · Fidel

3. Edi be thu, heven-queenë [2:22]

instrumental — Fidel · Harfe · Symphonia

4. Ar ne kuth ich sorghe non [4:49]

Formerly I knew no sorrow — B. Bagby · Fidel

5. Dance / Tanzstück / Danse [2:08]

Fidel

6. Jesu Cristes mildë moder [6:09]

Jesus Christ's gentle mother — B. Bagby · E. Brownless

7. Worldes blis ne last no throwë [11:29]

Worldly bliss — B. Thornton · Harfe

8. Instrumental [1:39]

Fidel

9. Fuwëles in the frith [0:46]

Birds in the woodland — B. Thornton · B. Bagby

10. Man mai longë lives weenë [6:56]

Man may expect long life — B. Thornton · Symphonia

11. Byrd onë brerë [2:15]

Bird on a briar — B. Thornton

12. Edi be thu · heven-queenë [2:35]

Blessed be thou · queen of heaven — B. Thornton · E.

Brownless

13. Ar ne kuth ich sorghe non [4:08]

instrumental Lai — Fidel · Harfe

SEQUENTIA

Ensemble für Musik des Mittelalters

Barbara Thornton · Gesang

Benjamin Bagby, Gesang, Harfe, Symphonia

Margriet Tindemans, Fidel

mit:

Edmund Brownless, Gesang

Instrumente

Zwei 5saitige Fideln von Fabrizio (Fonte Alto, Italy) 1978.

14saitige Harfe von Geoff Ralph (London)1981.

21saitige Harfe von Rainer Thurau ((Ulm) 1985.

Symphonia von Bernhard Ellis (Dilwyn, Herefordshire) 1978.

© 1988 by harmonia mundi, D-7800 Freiburg

Ⓟ 1989 by harmonia mundi, D-7800 Freiburg

Produzent: Klaus L. Neumann

Aufgenommen: 23.-25.V1.1987, Cedernsaal Schloß Kirchheim

Dr. Thomas Gallia · Paul Deny (Sonart, Milano)

Kommentar: Benjamin Bagby, Margriet Tindemans

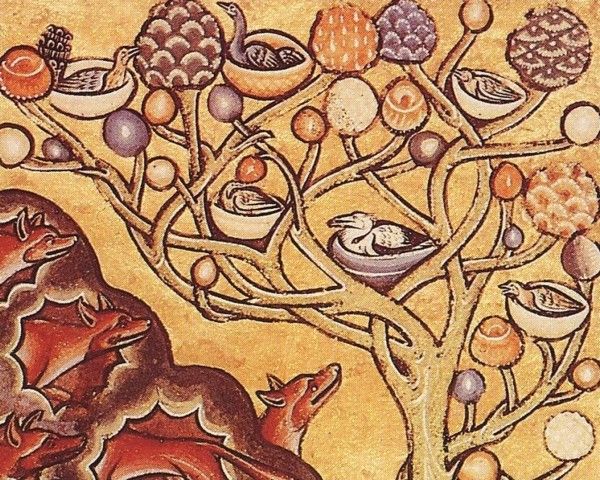

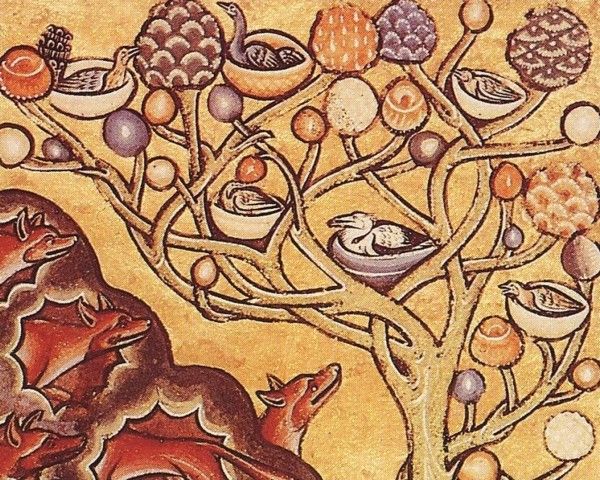

Titelseite:

Motiv: lat. 8846, f 3v. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

Gestaltung Vorderseite: B &M Wiesinger

Redaktion: Dr. Jens Markowsky, Rudolf Moratscheck

All rights reserved

HARMONIA MUNDI D-7800 FREIBURG

Eine Co-Produktion mit dem WDR, Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln

“Worldes blis” — English songs of the Middle Ages

The repertoire of songs in English from the 12th to the early 14th

centuries is surprisingly small. We know that much music composed to

English texts is lost to us (due to the oral mode of vernacular song

transmission), and must therefore content ourselves with the less than

two dozen pieces, some in fragmentary form, which have survived in a

variety of manuscript sources, including a saint's life, a book of

miscellaneous religious writings, and even the reverse side of a papal

bull. Unfortunately, there exist no large manuscript collections of

English song comparable to the chansonniers of the Troubadours and

Trouvères, since the courtly, literate, — and therefore

written — tradition in England before Chaucer's time was largely

French. Anglo-Norman song was the fashion amongst the aristocracy, and

those pieces with English texts which found their way into writing came

for the most part from a religious-scholastic milieu, such as the

Franciscans, in which English was prevalent.

In bringing these songs back to life, our point of departure has always

been to concentrate on the texts, as they are found in the original

musical sources as well as in published editions. Such comparative work

helps the singer to establish a working text, and can often shed light

on problems of meaning and emphasis, orthography and pronunciation.

Having a satisfactory basic text for a poem begins a long process of

interiorizing every aspect of the poet's art, from the acoustical

properties of the language (vowel and consonant sounds, rhyme, inner

rhyme, alliteration, etc.) to comprehending the sense of specific word

choices and rhetorical devices.

As this process continues, the singer realizes that a given edition is

often at odds with the text as found in the musical source, which can

be unclear or even garbled. Since our principle has been to depart from

the musical source as little as possible, we have chosen the manuscript

version when a text editor has made changes which would necessitate

modification of the musical setting. Sometimes the musical information

provided by the manuscripts is also ambiguous, or we have reason to

suspect scribal error. For instance, the final line of “Bryd one

brere” may be sung a third lower if one agrees that the scribe

made a mistake in placing a c-clef (we have chosen to record the

version as found in the manuscript).

In general, we have assumed that a written musical source is not an

Urtext of a song, but rather a written documentation — however

incomplete — of some stage in the song's active life. A

manuscript may represent a remembered performance, dictated or

otherwise transmitted to a scribe, or it might have a more direct

connection with the singer himself, or a musician from the original

singer's tradition.

The subject of rhythm in medieval song has generated much partisan

discussion. Given that the notation of these pieces is often

rhythmically ambiguous and open to various interpretations, we have

tried to avoid a dogmatic approach in favour of an evaluation of each

individual song. For example, “Edi be thu, heven-queene”

lends itself naturally to a simple rhythmic pattern based upon the

text, whereas “The milde Lomb” or “Worldes

blis” demonstrate a more subtle use of melody, and a style which

is essentially ornamental and impossible to fix in rhythmic units. In

another case, the sequence “Jesu Cristes milde moder”, we

have chosen a type of musical recitation which avoids rhythmic

regularity and follows the shifting patterns in the text. The

performance of “Bryd one brere” recorded here reflects the

inconsistent use of mensural notation found in the source, and hence,

re-creates a performance containing passages which the scribe would

have found difficult to notate using the symbols available to him.

Decisions about the use (or non-use) of instrumental accompaniment were

also made according to the character and structure of each song. An

accompaniment may consist of a simple drone, or it may employ the more

complex techniques of heterophony, mirroring and commentary, but in all

cases the melodic vocabulary of the instrumental part is derived from

the songs themselves or other pieces from English sources of the

period. For St. Godric's song in praise of St. Nicholas, the simple

melody has been amplified through techniques of polyphonic vocal

elaboration which would have been part of an oral tradition in medieval

clerical circles.

Benjamin Bagby

Notes on instrumental music

The definition of an “instrumental” style is a long process

and is possible only through a close study of the vocal repertoire. The

existing instrumental pieces, like the estampie in the Oxford MS

(Bodleian Library, MS Douce 139, f.5) give us some information about

forms and melodic structure, but they are very few and diverse, and do

not permit us to rebuild a tradition of instrumental playing using only

those sources.

From literary sources we know that vocal music was played on

instruments, but we have little information about how the material was

used in an instrumental performance. Given the specific possibilities

of each instrument and the fact that a large part of the instrumental

music served as dance music, it seems likely that the medieval

instrumentalist would re-arrange the material freely and add to known

melodies.

For the pieces on this record we have made use of simple dance forms,

such as the rondeau (“Edi be thu, heven-queene”, Nr. 3)

estampie (Oxford MS, Nr. 5 on this record), and the more complex lai

(“Ar

ne kuth ich sorghe non”, Nr. 13 on this record). The instrumental

arrangements were made by Margriet Tindemans, using melodic material

from the vocal pieces whose titles they bear. Sometimes melodies from

related songs were added; at other times we made and improvised new

melodies while staying as close as possible to the original material.

Margriet Tindemans