HILDEGARD von BINGEN

Canticles of Ecstasy

Sequentia

medieval.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) 05472 77320 2

1994

1. O vis aeternitatis [8:05]

responsorium · Laurie Monahan, ensemble, 2 Fideln, Organistrum

I. Symphoniae to Maria

2. Nunc aperuit nobis [1:53]

antiphon · Heather Knutson, Susanne Norin, ensemble

3. Quia ergo femina mortem instruxit [1:51]

antiphon · Janet Youngdahl

4. Cum processit factura digiti Dei [6:40]

antiphon · Janet Youngdahl, ensemble, 2 Fideln

5. Alma Redemptoris Mater [2:10]

Marian antiphon, 10.Jh. · ensemble

6. Ave Maria, O auctrix vite [9:04]

responsorium · Heather Knutson, ensemble, 2 Fideln

II. Symphoniae to Spirit

7. Spiritus Sanctus vivificans vite [2:17]

antiphon · Pamela Dellal

8. O Ignis spiritus Paracliti [6:26]

sequenz · Susanne Norin, ensemble

9. Caritas habundat in omnia [2:17]

antiphon · ensemble

III. Symphoniae to Maria

10. O virga mediatrix [2:28]

alleluia-antiphon · Laurie Monahan, Harfe

11. O virdissima virga, Ave [3:54]

lied · ensemble

12. Instrumental Piece [3:34]

E. Gaver, E. de Mircovich, B. Bagby

13. O Pastor Animarum [1:28]

gebet · Elizabeth Glen

14. O tu suavissima virga [11:23]

responsorium · Susane Norin, E. Gaver, ensemble

IV. Ecclesiastical Community

15. O choruscans stellarum [2:42]

antiphon · Barbara Thornton

16. O nobilissima viriditas [6:44]

responsorium · Gundula Anders, mit

Elizabeth Glen, Janet Youngdahl, ensemble

SEQUENTIA

Ensemble für Musik des Mittelalters

Gesang, BARBARA THORNTON

Barbara Thornton, Gundula Anders, Pamela Dellal, Elizabeth Glen,

Heather Knutson, Laurie Monahan, Susanne Norin, Janet Youngdahl

BENJAMIN BAGBY

Benajmin Bagby, mittelalterliche Harfe, Organistrum

Elisabeth Gaver, mittelalterliche Fidel

Elisabetta de Mircovich, mittelalterliche Fidel

Instrumentalbearbeitung · instrumental arrangements:

Benjamin Bagby, Elizabeth Gaver

Quellen/sources:

Musik/music:

Rupertsberger „Riesencodex” (1180-90) Wiesbaden: Hessische

Landesbibliothek, Ms. 2, f. 466 ff.

(Alle Stücke, die aus handschriftlichen Ausgaben musiziert werden,

basieren auf direkten Konsultationen mit Wiesbaden MS, eingerichtet von

Barbara Thornton. All pieces performed from diplomatic editions

based on direct consultation with Wiesbaden Ms, prepared by Barbara

Thornton.)

Lateinische Texte aus/latin texts from:

Hildegard von Bingen, Lieder.

Nach den Handschriften herausgegeben von/after the manuscripts

edited by

Pudentiana Barth OSB, M. Immaculata Ritscher OSB und/and Joseph

Schmidt-Görg. Salzburg, 1969.

Instrumente:

Fidel (E. Gaver): Rainer Ullreich, Wien 1991

Fidel (E. de Mircovich): Richard Earle, Basel 1988

Harfe: Geoff Ralph, London 1983

Organistrum: Alan Crumpler, Leominster, GB, 1982

Assistenzarbeit: Fabienne Carlier

Special thanks to:

Pastor Peter von Steinitz of St. Pantaleon, Köln and to

José Verstappen and members of the 1992 Vancouver Early Music

Festival concert ensemble and course participants for their support of

the Hildegard von Bingen project.

(P) + © 1994, BMG Music

Executive producer: Jan Höfermann

Producer: Klaus L. Neumann

Artistic recording supervision: Barbara Valentin

Technical recording supervision: Martin Andrae

Editing: Barbara Göbel

Recorded: 16.-21. June 1993,

St. Pantaleon, Köln, at the sarcophagus of the Empress Theophanu

(d. 990)

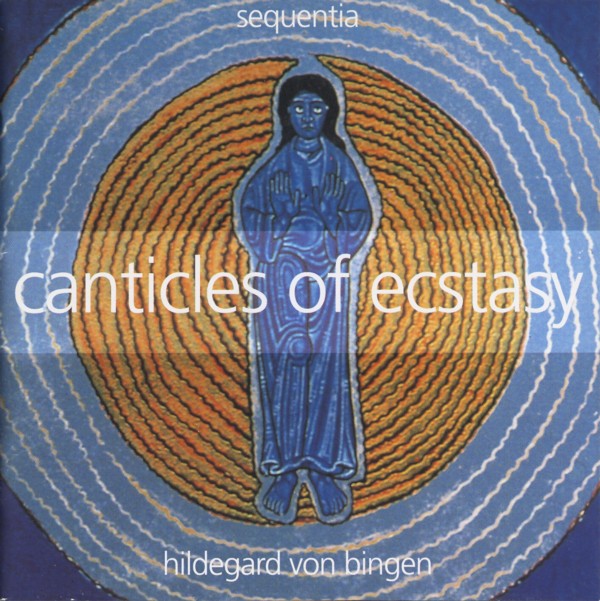

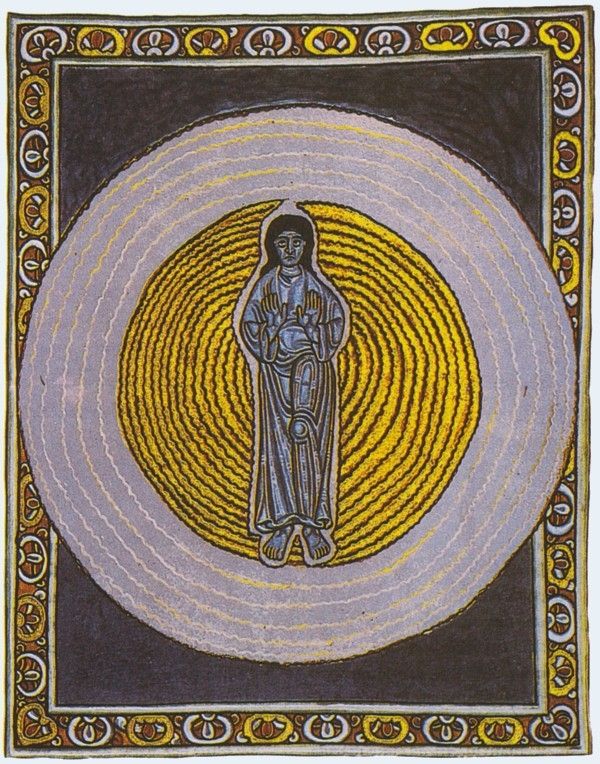

Front cover picture: Illustration to Hildegard's vision „The

Cosmos”

[sic; we believe it's „The

Trinity”]

(Das Weltall) from Scivias („Wisse die Wege/Know the

Ways”) Book I, Vision 3

Rupertsberger Scivias-Codex, Abtei St. Hildegard, Eibingen.

Copy of Wiesbaden: Landesbibliothek, Ms. 1, [missing since ca. 1944]

Photo Back cover: Marco Borggreve

Complete editing: Dr. Jens Markowsky

BMG

BERTELSMANN MUSIC GROUP

A co-production with Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln

Hildegard von Bingen's spiritual compositions represent a pinnacle of

individual creation in an distinguished age of art and thought. The

twelfth century is widely referred to as having witnessed a

“Renaissance” in the sense of a full cultural flowering,

and this reputation is largely due to the exceptional intellectual

vigor, philosophical depth, and aesthetic brilliance of the monastic

arts of the time. The manner in which theological renewal, economic

well-being, and far-reaching social innovations came together to

support monastic life accounts in part for the phenomenal musical and

literary output of Hildegard von Bingen and some of her contemporaries.

As of the age of eight, she lived the cloistered life according to

Benedictine Rule, first in the double (male and female) monastery

called Disibodenberg, west of the Rhine, and then, at the height of her

powers, as the leader of her own community at Rupertsberg on the Rhine

at Bingen. As abbess of Rupertsberg, Hildegard's authority, fame, and

creative power increased significantly. Between 1151 and 1158 she was

writing and collecting her musical compositions intended to be sung by

the sisters at the convent at liturgical and other functions. She

called them symphoniae harmoniae celestium revelationum, a

title meant to indicate their divine inspiration as well as the idea

that music is the highest form of human activity, mirroring as it does

the ineffable sounds of heavenly spheres and angel choirs. It was also

during this time that she carried out an extensive correspondence with

important personalities in ecclesiastical and temporal circles, as well

as turning her energies to compiling encyclopaedic works on natural

science and the healing arts.

In her own time, as in ours, the “Sibyl of the Rhine”

amazes those with the ears to hear her. “It is said that you are

raised to Heaven, that much is revealed to you, and that you bring

forth great writings, and discover new manners of song ...” wrote

Master Odo of Paris in 1148. Then, as now, she is admired for

fearlessly exploring the cosmos with her vision, for creating a moving

feminine theology which nonetheless remains in awe of both the

masculine and feminine divine powers. Her ability to function in the

real, political world is as impressive as her complete dedication to

the life of the soul, and to nurturing it among her cloistered sisters.

The Pieces

O vis aeternitatis

This composition begins the symphonia collection in the

Wiesbaden manuscript, which was prepared in Hildegard's own

scriptorium. It is a monumental piece which achieves its architecture

of profunda altitudine (her term: profound height) principally

through the responsory form: the alternations of solo and ensemble

singing. Hildegard has chosen the “indirect” and

“hidden” E-mode to depict the mysteries she dares approach.

Our musical setting is intended to show profound symphonia

(cosmic harmony) appropriate to Hildegard's universal themes of

incarnation and suffering.

I. Symphoniae to Maria

Nunc aperuit nobis porta clausa

Quia ergo femina morte instruxit

Cum processit factura digiti Dei

These three pieces form a thematic trilogy in the Wiesbaden Ms. The

first piece is written in a mode based on C which Hildegard habitually

reserves for passages of highest energy and significance (for example,

sections sung by the character Victoria in Ordo Virtutum).

In this piece she proclaims that the “door has now been

opened!” This is the “door to the mysteries” as

described in Isaiah 60:10. The closed door is the feminine principle

which has lived in the shadow of the Fall; the open door, the victory

of womankind as a reversal of the Fall of man and woman in Paradise.

The feeling of a curse being lifted is communicated with great

intensity. Quia ergo femina morte instruxit continues the

thought of the beginning piece, but its mode and message present a

contrast: the E-mode is of a sweet variety, as intimate and feminine as

the text (dulcissima et beata virgine: sweetest and most blessed

virgin), so that we understand this quality Hildegard considers to be

singular in the feminea forma (female form). Cum processit

factura digiti Dei completes the trilogy in lamenting E-mode

figures similar to those used in Ordo Virtutum and elsewhere

where the tragedy of human life is bewailed. Halfway through the piece,

in contemplation of the cosmic music which surrounds the divine Maria,

the same lugubrious E-mode reveals itself to be infinitely harmonious.

The instrumental prelude is constructed rhetorically using motives

derived from the words femina, feminea, Maria, virgo, and the

extensive melisma on sonante as found in Quia ergo and Cum

processit.

Alma Redemptoris Mater

Ave Maria, O auctrix vite

The first piece — not composed by Hildegard — is one of the

four Marian antiphons originally chanted in the office, but more

commonly sung as an independent piece, and traditionally thought to

have been written in the 10th century. What is immediately apparent in

this antiphon is the glowing joyfulness of its F-mode; in the modal

system it is heard as audaciously triadic and open. Hildegard's Ave

Maria, O auctrix vite was obviously composed as an elaborate

textual and musical embroidery of Alma Redemptoris Mater. In it

she constructs, again through the responsory form, a long narrative

history of the victorious Maria. The musical setting evokes the

Celestial Woman, surrounded by stars, planets, and moving spheres.

II. Symphoniae to Spirit

The Spirit searches out all things, yea the deep things of God

(I Corinthians 2:10)

Spiritus sanctus vivificans vite

O ignis spiritus Paracliti

Caritas habundat in omnia

By moving to the D-modality, a significant shift is achieved.

Contrasting E-mode and D-mode is a device we see throughout Hildegard's

opus, and it is used to great effect in Ordo Virtutum.

The D-mode is traditionally considered the fons et orgio

(source and origin) of all modes. Its emotional Affekt is most

noble and serious, yet it is more than any other mode adaptable to the

shades of expression in any poem. Through this very succinct and

powerful text we are able to understand that Spirit is the source and

origin of all life (“the life of life”). O ignis

spiritus Paracliti is one of the approximately nine sequentiae

in Hildegard's collection, and, like the others, progresses not in the

classic fashion with literal melodic repetitions (aa, bb, cc, etc.)

Rather, she once again has fashioned her ideas with a masterly sense of

variation by freely improvising on her stated themes in the repeat

sections, allowing her rich text to dictate emphases on consonance or

dissonance. The third piece in this trio, Caritas habundat in omnia

(sister piece to Spiritus Sanctus), speaks of Caritas,

the marvelously complex figure developed in Hildegard's opus,

who is at once the Bride of the Song of Songs, Divine Wisdom,

and Charity of the New Testament. She is the central character in a

vision in the cycle, Liber vitae meritorum (The Book of Life's

Merits), and is heard to say, “I am the air; I nourish all green

and growing life ... I am skilled in every breath of the Spirit ... so,

I pour out limpid streams.” A more melismatic, flowing use of

D-mode (which she colors variously) stimulates this special sense of

Love as World-Soul.

III. Symphoniae to Maria

O virga mediatrix

O viridissima virga

Instrumental piece

O pastor animarum

O tu suavissima virga

Like many medieval poets, Hildegard uses images of nature to arouse

“natural” yearnings for the divine: desire which carries resonances of Paradise and which seeks union with the Divine

Beloved. Some of these pieces are exalted through her visionary gift,

yet are grounded in the elements of this world. Each of these Marian

songs addresses the Virgin as virga (branch), and later as flos

(flower). As virga mediatrix she is the “mediating

branch”, and as pulcher flos, the “beautiful

flower.” Taking its tone from the initial Alleluia, this piece

reaches within its E-mode build up an ecstatic pitch in contemplation

of the innermost, life-giving part of Maria (viscera, womb).

Considered by many to be one of Hildegard's masterpieces, O

viridissima virga (most verdant branch) is realized in a G-mode.

This mode is associated with youthfulness and upward movement, and is

said to refresh the spirit, as it reflects the perfections of Paradise

before the Fall: “transcendit labores et erumnas”,

“transcends all earthly labors and tribulations”. Thus her

concatenations of earthy words are paraded before us as in a sacred

dance, their significance heightened by deft juxtapositions and musical

variation. The sense of sacred dance has been rendered in this

recording by having selected a special location in the body of the

church to sing from, and by the addition of an instrumental piece in

the same mode. A pastoral prayer, O Pastor animarum, interrupts

these evocations of the lush, natural world by invoking its heavenly

care-taker. The created world needs a World-Pastor, and with lamb-like

simplicity, Hildegard uses the primary D-mode and an utterly sincere

text to call out to Him. Maria is now a “most gentle

branch” (O tu suavissima virga), and her flower is bright (clarus

flos), probably in the sense of being made of light. The D-mode

here is given the color of the mystic E-mode through a lowered second

tone. The extreme visionary quality of the poem is haloed in music of

otherworldly beauty to illustrate the miracle of how spirit becomes

material.

IV. Ecclesiastical Community

O choruscans stellarum

O nobilissima viriditas

Ecclesia (Greek) is the place where spirit is received, be it in

a temple, or in the hearts of a people, and is thus synonymous with the

Hebrew synagoga. This song praises the feminine figure Ecclesia

in an exalted D-mode by likening her to certain Apocalyptic images. In

the second piece the Marian virga (branch) has become virgo

(virgin), and extolls companies of virgins. As understood in

traditional societies, a virgin was not necessarily a woman who had

never known a man, but one who had espoused herself, body and soul, to

Spirit; who, in a collective form, observed the liturgies of oracle,

temple, church, or monastery, and provided thereby a feminine spiritual

anchor to a temporal dynasty. This extraordinary C-mode composition

becomes progressively redder in its imagery and in musical intensity (rubes,

ardes, flammis). Elsewhere she has written that the gifts of

spirit gradually redden in the soul, deepening its native fire-red

nature with each experience.

Barbara Thornton