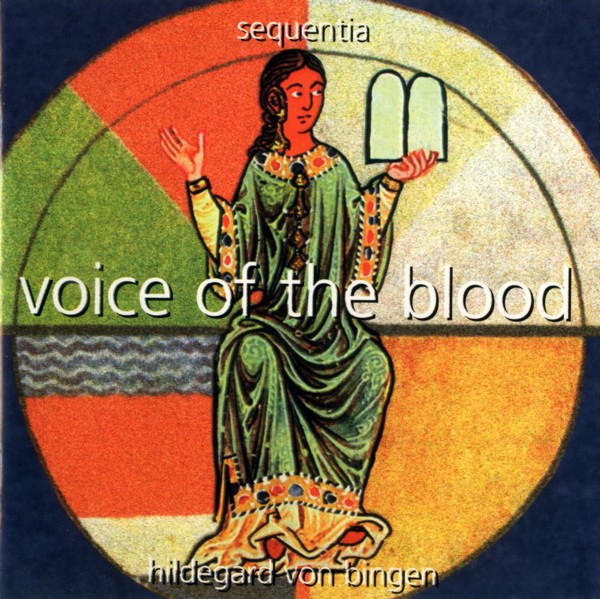

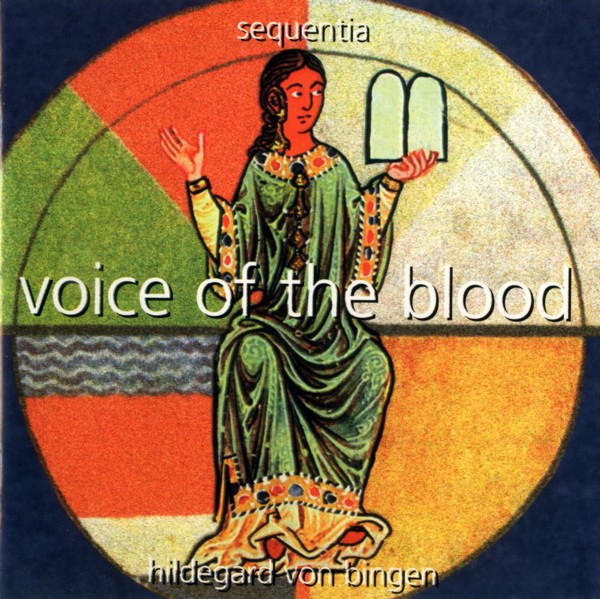

HILDEGARD von BINGEN / Sequentia

Voice of the Blood

medieval.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) 05472 77346 2

1995

1. O rubor sanguinis [2:03]

Antiphon to St. Ursula

Heather Knutson

2. Favus Distillans [8:29]

Responsory to St. Ursula and the 11,000 virgins

ensemble, fiddle, symphonia

3. Laus Trinitati [1:36]

Antiphon in Praise of the Trinity

Gundula Anders

4. In Matutinis Laudibus [9:53]

Office for the Feast of St. Ursula

1. Studium Divinitatis

2. Unde quocumque

3. De patria

4. Deus enim

5. Aer enim volat

6. Et ideo puellae

7. Deus enim rorem

8. Sed Diabolus

ensemble, intonation: Pamela Dellal,

Carol Schlaikjer, Elizabeth Glen, solo in 7.

5. O Ecclesia [7:57]

Free Sequence to St. Ursula

Barbara Thornton, ensemble

6. Instrumental Piece [6:34]

Elizabeth Gaver · based on 'O viridissima virga'

fiddle, portative organ, symphonia

7. O aeterne Deus [2:12]

Antiphon to God the Father

Janet Youngdahl

8. O dulcissime amator [6:46]

Symphonia of the virgins

solo: Pamela Dellal, Nancy Mayer, Consuelo Sañudo, Lucia Pahn

ensemble: Elizabeth Glen, Janet Youngdahl

9. Rex noster promptus est [6:25]

Responsory to the Innocent

ensemble, Lucia Pahn, organistrum

10. O cruor sanguinis [1:36]

Antiphon

Carol Schlaikjer

11. Cum vox sanguinis [6:32]

Hymn to St. Ursula

ensemble

12. Instrumental Piece [3:00]

Elizabeth Gaver, based on the D-modes of Hildegard

fiddle, portative organ

13. - [7:48]

O virgo Ecclesia

Antiphon for Ecclesia · ensemble, organistrum

Instrumental Piece

Elizabeth Gaver · fiddle

14. Nunc gaudeant materna [2:27]

Antiphon to Ecclesia

Gundula Anders, Elizabeth Glen, Carol Schlaikjer, Janet Youngdahl, ensemble

15. O orzchis Ecclesia [3:39]

Antiphon to Ecclesia

ensemble

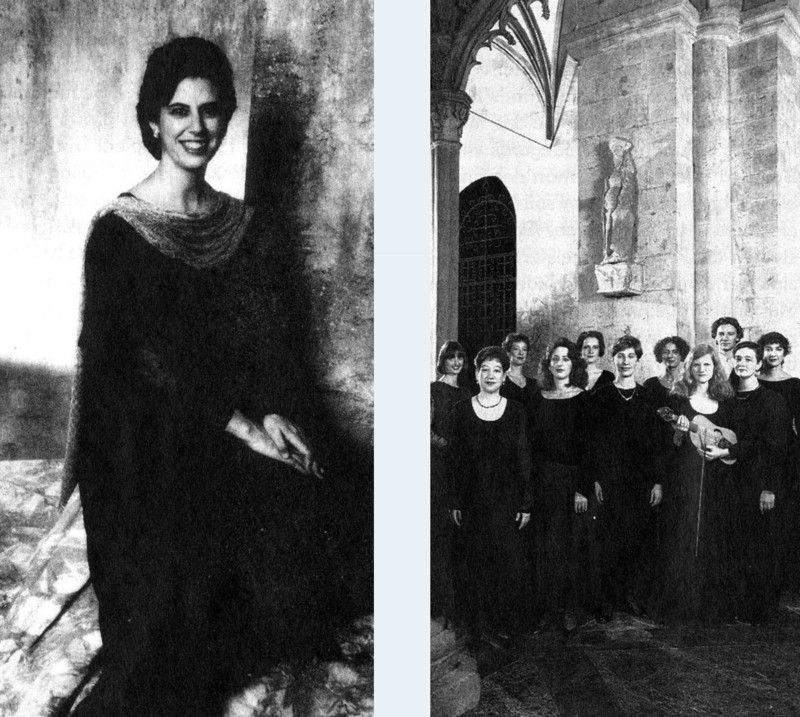

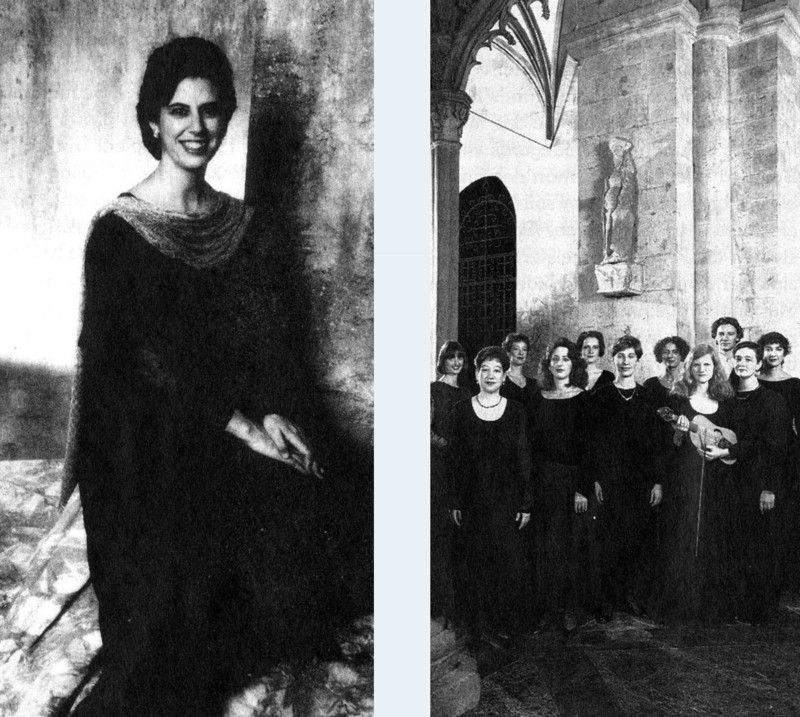

SEQUENTIA, Ensemble für Musik des Mittelalters

Barbara Thornton & Benjamin Bagby

Barbara Thornton, voice, portative organ

voices:

Elizabeth Glen, Janet Youngdahl, Carol Schlaikjer,

Nancy Mayer, Pamela Dellal, Heather Knutson,

Lucia Pahn, Consuelo Sañudo, Gundula Anders

Elizabeth Gaver, fiddle

Joachim Kühn, organistrum, symphonia

Instruments:

Fiddle: Rainer Ullreich, Wien 1991

Portative organ: Louis Huivenaar, Jan de Bruijn, Amsterdam 1983

Symphonia: Bernard Ellis, Dilwyn, Herefordshire, GB 1978

Organistrum: Alan Crumple, Leominster, GB 1982

Assistant to SEQUENTIA: Joachim Kühn

Assistance by Laurie Monahan and Elisabetta de Mircovich in

transcription work is greatly appreciated.

Arrangements:

Barbara Thornton, Elisabeth Gaver

All arrangements, transcriptions, and reconstructions of Hildegard von

Bingen's music by Barbara Thornton are protected under copyright law

and may not be used by others without express permission.

Latin texts from:

„Hildegard der Bingen. Louanges” Traduites du Latin et

présentées par Laurence Moulinier.

© Orphée / La Différence, Paris 1990.

Music sources:

Rupertsberger „Riesencodex” (1180-90) Wiesbaden: Hessische

Landesbibliothek, Ms. 2, f. 466 ff.

All pieces performed from diplomatic editions based on direct

consultation with Wiesbaden Ms, prepared by Barbara Thornton.

Dedication:

We dedicate this recording to the memory of all victims of violence.

(P) + (C) 1995 BMG Music

Executive producer: Jan Höfermann

Producer: Klaus L Neumann

Recording supervision: Barbara Valentin

Balance engineer: W. Sträßer

Editing: A. Plagmaker

Mastering: Andreas Neubronner (TRITONUS)

Recorded: 30. October-3. November 1994, St. Pantaleon, Köln

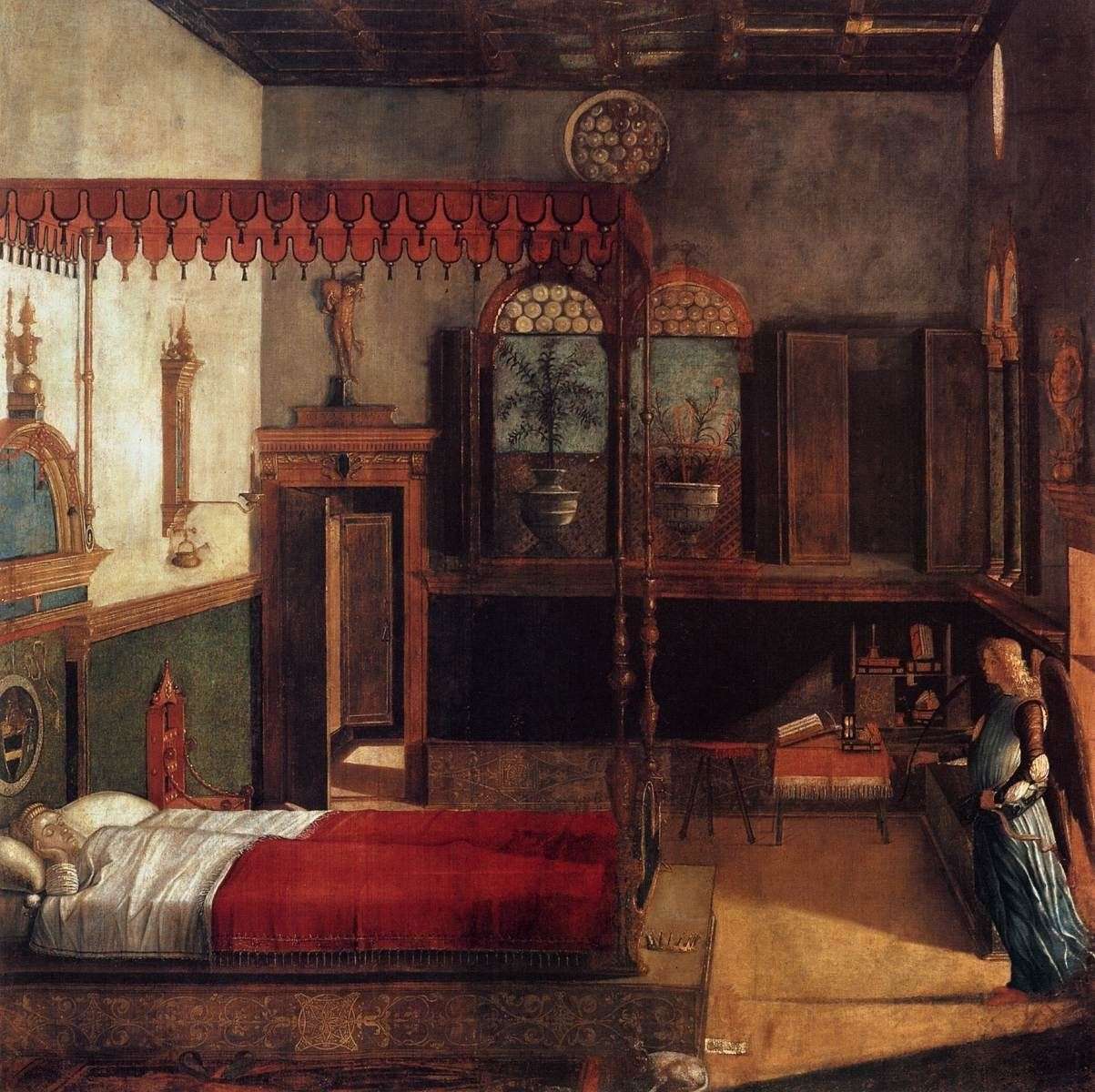

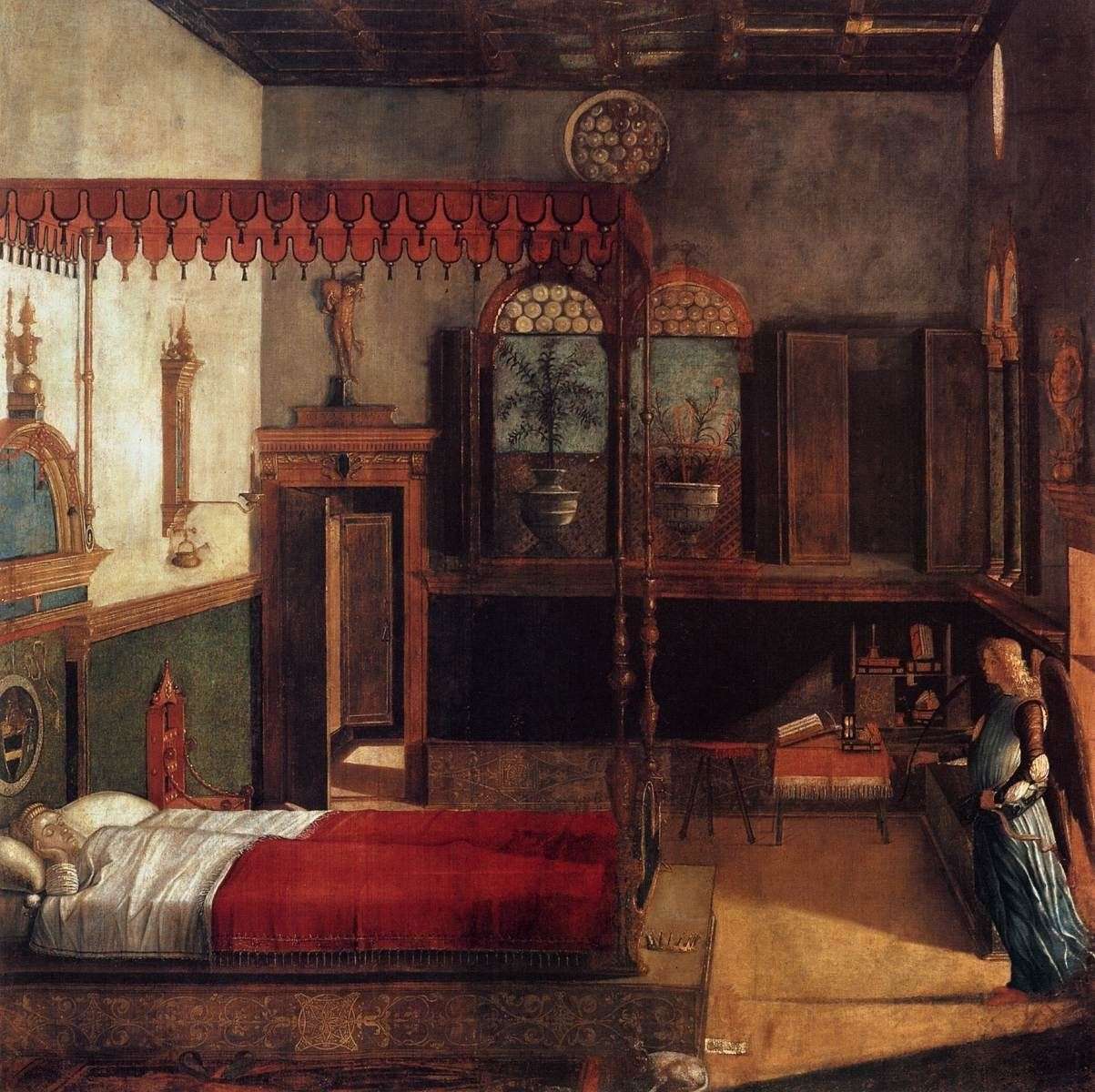

Front cover picture: Miniature from Codex Latinus 1942

Design: Ariola/Strada

Art direction: Thomas Sassenbach

Text editing: Dr. Jens Markowsky

All rights reserved

BMG / BERTELSMANN MUSIC GROUP

Eine Coproduktion mit Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln

This recording marks the second in the series of Sequentia's BMG/DHM

recorded productions of the complete musical works of Hildegard of

Bingen. The first, entitled Canticles of Ecstasy, presented a

selection of her compositions of relatively ambitious scope: Marian

songs possessing intricate theological and imagistic programs were

contrasted with similarly complex songs dedicated to the Holy Spirit.

Perceiving the Cosmos as animated by both a feminine and masculine

divine force, Hildegard was able in these praise-songs to give an

insight into the two opposite but equally powerful universal poles of

energy.

The present series of her symphoniae creates such

juxtapositions on a more specific, "human" level. In the story of

Ursula and the 11.000 virgins we see crystallized in the form of a

human woman the tenderness of nature, humility and receptiveness to

spirit which Hildegard found magnified to celestial proportions in

Maria, but also the rock-solid strength of virgin devotion which stands

up to misunderstanding, mockery, even death, allowing it to ultimately

partake in supra-terrestial celebrations of the blessed which await the

purest and most steadfast of souls.

Hildegard von Bingen's spiritual compositions represent a pinnacle of

individual creation in an distinguished age of art and thought. The

twelfth century is widely referred to as having witnessed a

"Renaissance" in the sense of a full cultural flowering, and this

reputation is largely due to the exceptional intellectual vigor,

philosophical depth, and aesthetic brilliance of the monastic arts of

the time. The manner in which theological renewal, economic well-being,

and far-reaching social innovations came together to support monastic

life accounts in part for the phenomenal musical and literary output of

Hildegard von Bingen and some of her contemporaries. As of the age of

eight, she lived the cloistered life according to Benedictine Rule,

first in the double (male and female) monastery called Disibodenberg,

west of the Rhine, and then, at the height of her powers, as the leader

of her own community at Rupertsberg on the Rhine at Bingen. As abbess

of Rupertsberg, Hildegard's authority, fame, and creative power

increased significantly. Between 1151 and 1158 she was writing and

collecting her musical compositions intended to be sung by the sisters

at the convent at liturgical and other functions. She called them symphoniae

harmoniae celestium revelationum, a title meant to indicate their

divine inspiration as well as the idea that music is the highest form

of human activity, mirroring as it does the ineffable sounds of

heavenly spheres and angel choirs. It was also during this thus that

she carried out an extensive correspondence with important

personalities in ecclesiastical and temporal circles, as well as

turning her energies to compiling encyclopaedic works on natural

science and the healing arts

In her own time, as in ours, the “Sibyl of the Rhine”

amazes those with the ears to hear her. “It is said that you are

raised to Heaven, that much is revealed to you, and that you bring

forth great writings, and discover new manners of song ...” wrote

Master Odo of Paris in 1148. Then, as now, she is admired for

fearlessly exploring the cosmos with her vision, for creating a moving

feminine theology which nonetheless remains in awe of both the

masculine and feminine divine powers. Her ability to function in the

real, political world is as impressive as her complete dedication to

the life of the soul, and to nurturing it among her cloistered sisters.

Ursula and Ecclesia: Myths and Meaning

Of all the subjects and personages which inhabit Hildegard's poetic

cosmos only the Virgin-Mother Maria received the homage of composition

more often than the saint and martyr, Ursula of Cologne. St. Ursula was

a young woman who, along with her companions, 11.000 virgins, was

reportedly martyred in that city by barbarian soldiers. As attested to

by a stone inscription from the IVth century (discovered in the IXth

century) her cult was an ancient and lively one, spreading throughout

Europe from its center at the church in Cologne which still bears her

name. In the 12th century worship of this saint reached an apogee due

to the discovery at the Ursula church site of an old Roman burial

ground full of bones purported to be the actual remains of the

slaughtered women. In addition, another cloistered visionary,

contemporary to Hildegard, Elisabeth of Schönau, was receiving

visions relating to the life and martyrdom of Ursula, causing a

feverish interest in her cult as a result. It is known that Elisabeth

and Hildegard were in correspondence, and perhaps shared this vital

interest in St. Ursula.

Her legend unfolds in a remote early-Christian time: She was the

daughter of baptized Breton royalty, and promised in marriage (under

duress) to the son of the King of England. Raised a Christian, she

resisted with horror the idea of marrying the barbarian English prince,

but was saved this fate by the visitation of an angel. He instructed

her to demand a three-year reprieve from the marriage promise, to

undertake a pilgrimage under royal and ecclesiastical patronage to

Rome, stopping in Mainz, Basel and Köln on the way in the company

of eleven other noblewomen (the number eleven seems to have mutated

into the traditional number 11.000 through scribal vagaries). Having

been enthusiastically received by the Pope in Rome, this crowd of

virgins met its tragic end while stopping in Cologne on their return

trip at a time when Attila the Hun was besieging the city (not a

historically defensible scenario, but a very colorful one just the

same). The 12th century fervor for Ursula's cult was expressed mainly

through trafficking in her relics (the newly-found bones from Cologne),

in numerous paraliturgical compositions dedicated to her, presumably

intended for her feast-day celebrations on October 21st, and in

relatively modest visual representations of her virgin followers. By

the 15th century the Ursula legend was favored by many masters, and can

be found in elaborately executed works such as frescoes, paintings, and

altar pieces, in all parts of Europe (the most notable being Memling's

altarpiece in Bruges and Carpaccio's canvas in Venice).

Hildegard's strong identification with this figure goes beyond the

enthusiasm demonstrated in her lifetime; as the leader of a spiritual

community for women, as the model of purity and love for the Divine, as

bearing up to the vicissitudes of outside opposition and the

responsibilities of inspired leadership, as a figura for the

apotheosis of the human soul within the sacred space of Ecclesia,

and for the ultimate realization of that sacredness in eternal space

and time, she found in the figure of Ursula a thematic complex around

which her fondest poetic fictions could freely pivot. Musically, she

was able to achieve something like a “song-cycle” which

begins with the simple image of the redness of shed blood and ends in

the grand visions of Ecclesia in all the tragedy and

magnificence which tradition bestows on this figure.

Ecclesia is the Latin form of a similar Greek word meaning

"gathering", "assembly". Thus it is literally synonymous with the word

"synagogue", (also Greek). Before this word came to signify "church",

as a church building, or the Christian Church, it represented the idea

of a collective, per se: a people before its god, or even the space

suited to receiving spirit, be it within the soul of an individual or

within a community. In the course of centuries the concept was

expressed in the form of a female figure rich in amplifications and

resonances, as attested to in numerous examples of ecclesiastical

iconography and textual exegesis. She was the archetypical, eternal

Heavenly Community; Jerusalem, or the daughter of Jerusalem; the

mountain of Zion; She was the original and final manifestation of those

in union with God: Bride and Beloved of Solomon, of Christ; their

temple, synagogue, church; She was the epiphany of the feminine: the

very soul itself, the soul of a people, or of a people living in

expectation of union with its god-eternally existing, eternally waiting

to become the divine dwelling for Divine Wisdom. We learn through

Hildegard's Ursula works that the saint greatly desired to make of

herself that dwelling place for Wisdom, and that the force of her

personal Ecclesia created a multitude of similarly dedicated

women around herself. Certainly the same could be said of Hildegard von

Bingen.

In the Embrace of Ecclesia

We present here a series of Hildegard's compositions with reference to

her own programmatic positioning of pieces in the manuscript created at

her abbey, and according to thematic and formal groupings. This effort

has been aided by the invaluable insights provided by two of the

leading Hildegard scholars today: Peter Dronke and Barbara Newman. (For

more detailed treatment of these poems the reader should refer to the

works of these authors). A veritable dramaturgy results from aligning

the pieces in their present order, whereby we perceive that Hildegard

has woven together through the immediacy of her images and personages

themes which spring from the Biblical text traditions of Song of Songs,

and the Apocalypse, and the early Christian figure of Ecclesia.

The pieces

1.) O RUBOR SANGUINIS

The cycle opens with the searing image of red blood flowing between

Heaven and Earth, the most binding of covenants. Through mere hints in

her text and a masterfully succinct melody, we feel the horror of death

transformed into contemplation of it as a tender, eternal flower.

2.) FAVUS DISTILLANS

Opens to a world of nature and longing reminsiscent of the Song of

Songs: Mel et lac sub lingua eius: “honey and milk

beneath her tongue” implies the complete fulfillment of all

higher senses and desires. To show the snow-white purity of Ursula and

her multitude they are likened to a garden of apple-blossoms.

3.) LAUS TRINITATI

An energetic exclamation to the Trinity as an animating force closes

off this vision of Paradise as a call to worship to begin the quasi

story-telling cycle of antiphons which immediately follows.

4.) IN MATUTINIS LAUDIBUS This cycle was surely intended

to be sung at Hildegard's cloister during the canonical hours, and in

praise of Ursula on her feast-day (October 21). It attests to the fact

that such special days in the church year most have been richly

celebrated, and have served as outlets for Hildegard's compositional

skill. This marvelously constructed series combines the actual story of

Ursula with some very specific ideas Hildegard wanted emphasized: It

alternates between the traditionally designated feminine E-modes (i.e.

antiphons 4, 7) and the masculine dignity of the D-modes (i.e.

antiphons 6, 8), thereby favoring us with insights into her stated

concept of how females' very particular sort of spirituality rests upon

and is protected by the fundament of male organization and authority.

(Hildegard has occasion in her life to both profit and suffer from this

perceived natural order). A bold truth of life finds expression in the

concluding D-mode piece: ... Qua nullum opus Dei intacta dimisit:

“... for no work of God's remains untarnished”.

5.) O ECCLESIA

Barbara Newman claims this piece as “one of Hildegard's most

stunning achievements”; surely the same could be said of Newman's

analysis of it in her edition of translations of the Symphoniae.

Peter Dronke has written of the opening address to Ecclesia,

“Hildegard begins with an astonishing composite image, laden with

prophetic and mystical associations from the Old Testament. In her

visions in Scivias, and in the illuminations made under her

supervision to accompany them, Ecclesia is seen as larger than

life, but still as a recognizable womanly figure. Here Ecclesia

is a figure of cosmic dimensions, and Hildegard does away with the last

traces of realism. The sapphire of her eyes evokes the throne in

Ezekiel's vision of the Son of Man; her ears, the porta caeli

(Heavenly gates) of Jacob's dream, where earth and heaven seemed

nearest to each other; her nose, the fragrant place where the lover in

the Song of Songs waits for his bride; her mouth evokes that roar of

waves which, coming from the wings of the four living creatures, seemed

to Ezekial ‘quasi sonum sublimis Dei’ (‘like to the

sublime sound of God’)”.

This sublime quality of the poem, and its ambitious range, are

beautifully captured in Hildegard's D-mode tour de force setting. The

opening strophes are drenched in the emotion of “desiring

desire” which is Ursula's; as she is put to the test in this

desire, so does the music of the piece gain in complexity. Extremes of

range and of mode are employed for the painting of images such as

“purest ether” (purissime aere), “fiery

burden” (ignea sarcina), “the devil's members

invaded” (= agents of destruction in the world, membra sui

invasit). Decorative and expressive gestures ornament words like

“pearls from the matter of the Word of God” (margaritis

materie Verbi Dei), “desired with desire” (desiderio

desideravit), and “murdered” (occiderunt).

Hildegard even bursts out of the Latin tongue with the German

ecclamation of profound grief, “Wach!” at the

moment when Ursula's blood sacrifice is heard from the earth below by

the powers and elements of the universe above.

6.) INSTRUMENTAL PIECE

The following instrumental piece in G-mode, constructed by Elizabeth

Gaver, weaves together both freely and in a stately structure some of

the most tender of Hildegard's 8th-mode gestures. As this mode in the

12th century was thought to be most indicative of the state of

blessedness, bestowing upon the listener inner peace and meditative

quiet, its effect is to offer comfort after the harsh realities put

forth in the last antiphon of the foregoing cycle.

7.) O AETERNE DEUS / 8.) O DULCISSIME AMATOR

This individual prayer serves as a prelude to the subsequent communal

one: in Hildegard's rubric it is dedicated to the virgins, but should

perhaps be conceived as being sung by the virgins who “in

Ecclesia” and like Ursula, direct their ardor to the Highest

Love, the highest Lover.

“In your blood we were wed to you”, echoes words which

could be spoken by the figure of Ecclesia, who is often

pictured beneath the crucified Christ with a chalice to catch the blood

spilling from his side. All the pity and passion of such complete

identification with a divine lord, and awe for the miracles of embodied

divinity are heard through sneaky, arousing E-mode incantations, both

individual and “in symphonia”.

9.) REX NOSTER PROMPTUS EST

Receiving blood-sacrifice from earth, “Angels sound harmoniously,

and in praise together, but the clouds weep for their (the innocents)

shed blood”.

This strong, stark E-mode piece reminds us that, while Heaven rejoices

and builds its eternal city through the purity of souls who have

sacrificed themselves through love of the Divine, the extreme pain of

sacrifice is felt on this earth. Hildegard is able to reflect both the

majesty and the sorrow of these ideas through one and the same mode.

10.) O CRUOR SANGUINIS / 11.) CUM VOX SANGUINIS

The short antiphon confronts us once more with the sadness of innocent

bloodshed. While written in the same mode as O rubor sanguinis,

it seems to address our human feelings in the face of such tragedy,

here serving as a prelude to the next piece, a visionary

“Ordo” which plays itself out in cosmic time and space.

This composition constitutes one of Hildegard's major works. It begins

again with the image of blood: the blood of sacrifice which in its

agony cries out to Heaven where it is heard and received and submitted

to transformations. The drama of this vision is accomplished through

the unending powers of invention which are Hildegard's as she molds the

classic D-mode figures around her procession of images springing from

Old Testament events, myths, prophetic lore, and the Ursula legend.

Hildegard of Bingen uses the Old Testament topologies which show the

dynamics (and dangers) of human convenant with Divinity to foreshadow

Ursula's own relationship to her God and to her sacrifice. The ram

caught in the thicket is the innocent animal God substitutes for the

blood sacrifice Abraham is asked to make of his only son to Jahweh

(Gen. 22,13). God appears directly to Abraham in Mamre (Gen. 18,1), but

turns his back on him later (Ex. 33, 20) saying, “No man shall

see me and live”. The Biblical book Leviticus spells out the

ancient protocols of meat sacrifices. When He shows Himself to Moses,

He does so as a burning bush (Ex. 3, 1-4). By invoking the old and

innovating anew she apotheosizes Ursula's devotion: we learn that in

Heaven she loses her earthly name, Ursula, (meaning

“she-bear”, symbol of earthly spiritual strength) and is

given the heavenly name “Columba” (meaning

“dove”, symbol not only of the purity of her own soul, but

of the congregation of pure feminine souls around her, a kind of “ecclesia”.)

Ecclesia in person is invoked at the end as the piece climaxes

in a vision derived from the one found in the Biblical Apocalypse where

New Jerusalem's 12 gates are seen to be built of 12 precious stones

(here she mentions sapphire, topaz, and gold of the whole city).

12.) INSTRUMENTAL PIECE

This composition reflects the noble generosity of the D-modes of

Hildegard's antiphon cycle, (piece 4, antiphones 6,8). In it we can

feel the joy and glittering brightness of the foregoing

Jerusalem-vision.

13.) O VIRGO ECCLESIA / 14.) NUNC GAUDEANT

/ 15.) O ORZCHIS ECCLESIA

In Hildegard's manuscript, the songs dedicated to Ursula are followed

by Ecclesia pieces. The first of the series begins with a

bitter lament addressed to Ecclesia who is pictured here as

both virgin and mother whose children have been ripped away from her

sacred, protecting viscera by vicious wolves. Rarely has Hildegard used

such strong language, both verbal and modal, to arouse our

understanding of the suffering of separation from Spirit. As a postlude

we give expression to the sorrow of such pain in a fiddle piece

constructed by Elizabeth Gayer which also emphasizes figures in E-mode

capturing the extreme emotions of the lament to Ecclesia. The

suffering is immediately dispersed in this, one of Hildegard's most

exuberant pieces which rejoices at the restoration of souls to Ecclesia's

embrace. The cycle concludes in otherworldly solemnity achieved by her

giving the E-mode an ethereal manifestation, and in texts partially

written in Hildegard's lingua ignota, or secret language. Privy

to visions, both aural and optical, which surpassed her abilities of

expression, she devised a vocabulary of words (a mixture of Latin and

German) needed to give utterance to the unutterable things she saw and

heard. In her musical works she resorted to her secret language only in

this piece in order to render something of the mystery of Ecclesia

— realized and unrealized community of Spirit.

Barbara Thornton