medieval.org

sequentia.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 82876 58939-2

2004

I. HARFENLIEDER

1. Felix qui potuit boni [9:59]

tutti: 2 Leiern, Gesang | Solisten: EM, BB

2. Caute cane, cantor care [2:29]

tutti: 2 Leiern, Gesang | Solistin: AC

3. Magnus cesar Otto [6:24]

2 Leiern, Gesang: EM, BB

4. Rota modos arte [3:13]

tutti: Flöte, Gesang | Solistin: AC

05. David reges inclita proles [3:48]

tutti: Harfe, Flöte, Gesang | Solist: BB

II. DAS BILD DER MORGENDÄMMERUNG

6. Cigni [3:03]

Flöte aus Schawanneknochen | Solist: NR

7. Foebus abierat [5:57]

Harfe: BB, Gesang: AC

8. Clangam, filii [4:06]

Gesang: EM

9. Phebi claro [2:35]

Gesang und Leier: BB

10. Aurea personet lira [7:00]

tutti: Flöte, Harfe, Gesang | Solisten: BB, EM

III. SEHNSUCHT UND VERFÜHRUNG

11. Iam, dulcis amica, venito [4:26]

Gesang: EM, AC

12. Advertite, omnes populi [8:29]

tutti: 2 Leiern, Gesang | Solisten: BB, EM AC

13. O admirabile Veneris idolum [3:15]

2 Leiern, Gesang: AC

14. Puella turbata [2:50]

Flöte: NR, Harfe: BB

15. Suavissima nunna [4:28]

tutti: Harfe, Flöte, Gesang | Solisten: EM, AC, BB

16. Veni, delectissime [2:27]

tutti: Flöte, Harfe, Gesang | Solistin: AC

SEQUENTIA

Benjamin Bagby

Agnethe Christensen, Gesang

Eric Mentzel, Gesang

Benjamin Bagby, Gesang, Leier, Harfe

Norbert Rodenkirchen, Flöte, Leier

BARBARA THORNTON

(1950-1998)

IN MEMORIAM

"... when

the minstrel had arrived, once the fee had been arranged and he began

to take the lyre from its bullhide case, people rushed up... and they

watched with glued eyes and a hushed murmur as the performer ran his

fingers over the strings that he had fashioned from moist sheepgut; and

as the melodious strings resounded, sometimes tenuous and sometimes

raucous... he caused them to accord frequently in a fifth. He began to

perform of how the sling of a shepherd laid low great Goliath, how a sly

little Swabian deceived his wife with a trick similar to her own, how

perceptive Pythagoras laid bare the eight tones of song, and how pure

the voice of the nightingale is." Sextus Amarcius Gallus Piostratus, Sermones (Speyer, ca. 1050)

What

did secular European song sound like one thousand years ago? Who were

its singers and what instruments did they play? Where, and under what

circumstances, have their songs survived? Can we ever hope to

reconstruct music from such a distant age? These are the questions which

led to my initial search for the lost songs of a performing musician

whose name remains unknown to us, a search which now culminates — or at

least pauses for reflection — in this recording: Lost Songs of a

Rhineland Harper. Benjamin Bagby

P + C 2004 BMG Ariola Classics GmbH

Recorded: 26-30 September, 2002

DeutschlandRadio, Sendesaal des Funkauses Köln

Executive producers: Aurelius Donath, Dr. Richard Lorber (WDR),

Ludwig Rink (DeutschlandRadio)

A & R direction: Deborah Surdi

Musical producer: Elizabeth Ostrow

SACD recording engineer: Hein Dekker

Balance engineer: John Newton

SACD editor and SACD mastering: Philipp Nedel

PCM mastering: Mark Donahue

Product management: Nicola Kremer

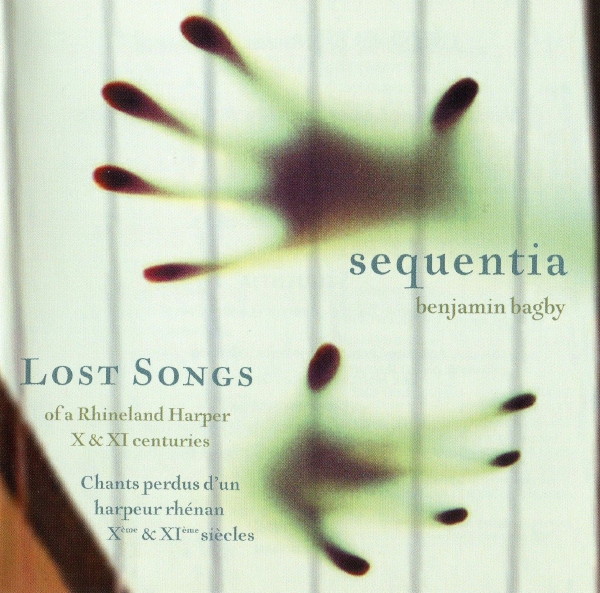

Front cover: © photodisc red (photo:John Slater)/

photodisc green (photo: C Squared Studios)/getty images

Design: Christine Schweitzer, Köln

www.schweitzer-design.de

Text editing: Jens Markowsky

All rights reserved

A co-production with

Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln DeutschlandRadio

Sources:

Text [t]:

The source for most of the songs in this recording is the manuscript Cambridge, University Library, MS Gg.5.35 in the edition:

The Cambridge Songs

(Carmina Cantabrigiensia) edited and translated by

Jan Ziolkowski [JZ],

Garland Library of Medieval Literature, vol. 66, series A, 1994 [= CC];

reprinted as

Medieval & Renaissance Texts and Studies, volume 192, Tempe, Arizona 1998.

Several

of the songs from this and other sources recorded here have relied on

editions and translations by

Peter Dronke [PD],including those found in

his books

Medieval Latin and the Rise of European Love-Lyric (2nd ed., Oxford, 1968),

The Medieval Lyric (3rd ed., Cambridge, 1996) and

The Medieval Poet and His World (Rome, 1984).

All other text sources are noted below.

Music [m]:

Sources

of European secular song containing musical notation from before the

12th century are rare and often difficult to decipher. In some cases, a

song survives in a later source which may - or may not - reflect the

"original" melody; in other cases, we may rely on the technique of

contrafactum to restore a melody; or, based on a knowledge of modes and

liturgical chant, we might attempt a transcription - or even a

reconstruction - based on neumes which do not always contain precise

pitch information. Except where noted otherwise, the musical

realizations in this recording are based on reconstructions made by

Benjamin Bagby [BB].

1.) t: Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy, Loeb Classical Library edition;

2.) t: JZ; 3.) t:JZ; 4.) t:JZ; 5.) t:JZ;

6.) m: instrumental arrangement: Norbert Rodenkirchen, based on nr. 8 below;

7.) t: PD / m: based on Paris, BN, n.a.l. 3126, fol. 90v., transcription: BB;

8.) t & m: Oxford Bodl, Libr. 775, fols. 129 & 176v-177v., transcription and edition: Bruno Stäblein;

9.) t: PD / m: Bibl. Apost. Vaticana, Cod. Vat. Reg. 1462, fol. 51, transcription: BB;

10.) t: JZ / m: Firenze, S.M. Novella, conventi sopressi 565, fol. 4v, transcription: Katarina Livljanic;

11.) t: PD / m: Paris, BN flat. 1118, fol. 247. transcription: BB;

12.) t: JZ;

13.)

t: JZ / m: based on the mss. Monte Cassino, Archivio dell' Abbazia,

codex 318, s. 291 and Bibl. Apost. Vaticana, lat. 3227, fol. 80v CO Roma

nobilis');

14.) m: instrumental arrangement: BB, based on the Notker sequence 'Scalam ad caelos', transcription: Richard Crocker;

15.) t: PD as reprinted in JZ;

16.) PD as given in JZ.

Instruments:

6-string Germanic lyres

copied from a 7th-century instrument found near Oberflacht, Germany;

made by Rainer Thurau (Wiesbaden, Germany, 1997 & 2001).

14-string harp copied from 12th-century sculpture in Chartres Cathedral, France; made by Geoff Ralph (London, 1983). Swan-bone flute, copied from 10th century instrument found near Speyer, Germany; made by Friedrich von Huene (Boston, 1998).

Wooden flutes made by Neidhart Bousset (Berlin, 1992-98).

Thanks:

We

wish to thank Peter Dronke (Cambridge, England), who has collaborated

with Sequentia on a number of recording projects since 1982. With his

invitation to perform a program of 11c songs at the Third International

Medieval Latin Congress in Cambridge, in September 1998, he provided the

initial spark which gave birth to this project. Many of the songs he

proposed for that program are found on this recording.

Thanks also to

Jan Ziolkowski (Cambridge, USA), whose study of the Cambridge Songs

(see: Sources) proved to be a treasure-trove of information and a source

of continued inspiration in the development of this program.

LOST SONGS OF A RHINELAND HARPER

Almost one thousand years ago a collection of

Latin and German song was copied into a manuscript by Anglo-Saxon monks

in the Abbey of St. Augustine in Canterbury. The original source - or

sources - has long since disappeared, but the manuscript copy has

survived to this day, and is now found in the library of Cambridge

University (Cambridge, University Library, MS Gg.5.35) where the

collection is generally known today as the Carmina Cantabrigiensia, or

The Cambridge Songs [CC]. Although we will never know what its exact

origin was, one thing is clear: many of the songs copied by the monks

come from the milieu of learned, aristocratic churchmen in the

Rhineland, where cities such as Cologne, Mainz, Worms and Speyer were

centers of culture and power in Ottonian Germany at the turn of the

first millennium. In addition, it is striking that many of the song

texts from this collection display an intimate working knowledge of

music, the voice, and instruments, especially the harp (cithara, lira)

and even the flute (tibia). When considering possible sources of the

Canterbury collection, the evidence points strongly to the performance

repertoire of a learned citharista, a bi-lingual harper/singer from the

Rhineland, whose songs delighted not only aristocratic bishops and their

courts, but also powerful abbots, secular - even imperial - nobility,

and the young clerical intelligentsia of those bustling river towns with

their imposing cathedrals, and of course, their grammar schools (not

surprisingly, some of the texts are didactic in nature). Here we have

the songs of a sophisticated professional entertainer whose erudite

audience was expected to pay for his services (and he might easily have

been joined on occasion by another minstrel from the ranks of the

itinerant players, or even a poetically-inclined clerical cantor).

In

addition to several musical reconstructions from the Canterbury

manuscript, this recording includes some of the earliest Latin secular

songs (and instrumental pieces based on such songs) which have survived

elsewhere in European manuscripts with musical notation. Certainly,

these songs would have travelled to the Rhineland, just as the harper's

repertoire found its way to England, where it had the good fortune to be

copied and to survive. And so, when a song from the Canterbury

collection is attributed here to "Rhineland, early 11th century", we are

speaking of the lost songbook itself, since we cannot know the previous

history of the piece, or if it was a new creation of that particular

time and place; its deeper origins - whether Frankish, Italian,

Aquitanian or Anglo-Saxon - often remain obscure. Still, in this wider

European context, we are afforded at least a brief glimpse into the

deliciously subtle, long-lost world of an unknown Rhineland entertainer

and his 11th-century audience.

I. SONGS OF THE HARP

In the

10th and 11th centuries, two types of harp (variously known in Latin as

harpa, lira, cithara) were known: an archaic, rectangular shape with a

very few strings all of the same length, and the more familiar,

triangular shape with many more strings of varying lengths. From the

Canterbury manuscript, these are songs about the harp, harpers, or songs

of praise to the harp itself: instrument of kings, gods, magicians, an

instrument whose strings vibrate in the hands of the harper like the

human soul resonating in the hands of the Creator.

Felix qui potuit boni (CC 76)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

This is a setting of one of the metra from the Consolation of Philosophy

written by Boethius (d. 524), a Roman aristocrat, philosopher, and the

author of a learned treatise on music which was venerated throughout the

Middle Ages.This lyric tells of the mythological singer and harper

Orpheus, describing his daring voyage into the realm of the dead to

rescue his beloved wife, Eurydice, through the power of song. The fact

that this song (and many other lyrics from the Consolation) turns

up in the Rhineland harper's collection almost 500 years later attests

to its great fame - and the power of the Orpheus myth in musical circles

- throughout the early Middle Ages.

Caute cane, cantor care (CC 30)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

A playful meditation on the role of the human body and soul as instrumentum

in the praise of God, in which the sinews of man become strings of the

harp, and his larynx becomes a flute. Astonishingly, each word of this

virtuosic text - which was possibly designed to function as a prelude to

a longer work, since lost - begins with the letter 'c'.

Magnus cesar Otto (CC 11)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

A

song in honour of the three German emperors named Otto, beginning with

Otto I "The Great" (936-973), who defeated the invading Hungarians. The

praise-song is preceded by an introduction explaining the title: it

seems that the Kaiser slept soundly as his palace caught fire one night.

His servants, afraid to disturb his sleep, finally called Otto's

harper, who played this tune until the emperor woke up and was able to

escape the flames. The harper had saved his master's life - and the

empire - and in memory of this event the song was immortalized as Modus Ottinc

("the tune known as Otto"). The likely date of composition for this

song is between 996 and 1002, making it something truly millennial for

us today. The musical reconstruction draws upon the medieval tradition

of the Laudes regiae.

Rota modos arte (CC 45)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

Dismissed

by one 20th-century German scholar as a "worthless object", this song

praises not only the harp, but the entire cosmos which it embodies, and

which is represented in Pythagorian theory by musical measure as

represented in number and ratio. In this musical reconstruction,

an attempt has been made to envision an 11th-century Rhenish monastic

tradition of melodic extemporization in the e-modus, especially in the

singing of texts relating to cosmic harmony and wisdom. Such a tradition

would have reached its apogee in the works of another Rhineland

musician, Hildegard von Bingen (who was born in 1098), many generations

later.

David regis inclita proles (CC 81)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

Beginning

with King David (after Orpheus, the greatest legendary harper), this

song seems to put harps into the hands of almost everyone in the

universe, praising God, with an ecstatic refrain (Davitice Davitice Davitice

= "in the manner of David") which repeats like a mantra. Although this

joyful, strophic refrain-song is in the form of an introductory trope on

the liturgical Sanctus text, it is unlikely that it was sung in

the celebration of the Mass, where — ironically — a harper's presence

would not have been welcome.

II. THE IMAGE OF DAWN

The most poignant medieval images of dawn, known to us from the troubadours, are found in the erotic alba,

a song of illicit lovers who must part after a night of secret delight.

But many dawn songs do not describe an amourous parting: there are also

songs which present the ineffable moment between night and day, when

mysteries are made manifest, the light in the sky is in flux, visions

occur, and voices of warning are heard mixed with the song of the

nightingale. Here, as in the Song of Songs, the worlds of eros and the

spirit are inseparable.

Cigni

(Frankish, 10c)

Almost

no instrumental music survives in written form from the period before

1200, and yet we know that instrumental music was performed with great

sophistication at all sorts of courtly and ecclesiastical gatherings.

Often, such pieces had exotic titles, attesting to their popularity, or

to an association with a certain story or mythological character. This

tune, found in numerous vocal manuscripts, is called "the swan" and is

related to the lament of the swan heard later in this recording (Nr. 8).

It is performed here in an instrumental version by Norbert

Rodenkirchen, who honours the famous tune by playing a tiny flute made

from a delicate swan's bone. The 11c remains of just such an instrument

were found in a castle near Speyer.

Foebus abierat

(Northern Italy, late 10c)

This

woman's song is the earliest-known depiction of a lover's ghostly

apparition, a theme which has haunted folksong for a thousand years.

Part of an ancient and important tradition, this song shares aspects of

its text (and probably also its melody) with other medieval depictions

of ghostly night-meetings between a man and a woman, including the

Beloved in the Song of Songs, and Maria Magdalena's meeting in the

garden with the resurrected Jesus.

Clangam filii

(Aquitaine, late 9c)

Called Planctus cigni (the swan's lament) this sequence (Latin: seguentia)

may have had its origins in indigenous song traditions of Aquitaine.

Its archaic theme of the soul's longing is made poignant through the

voice of a swan, the lost wanderer over the dark ocean, seeking

nourishment and a safe haven, and finding salvation by the light of

dawn. Although the text survives in several sources, the musical version

performed here is based on an 11c liturgical manuscript from

Winchester; this melody would probably have been known to the monks in

Canterbury who copied the CC manuscript, and to their brethren in German

lands as well.

Phebi claro

(Provence, late 10c)

This

Latin song, with its Provençal refrain, survives in a single

10th-century manuscript. Does it describe the plight of illicit lovers,

or is it (as Peter Dronke has argued) a warning to believers (the milites Christi

— soldiers of Christ), to watch for pre-dawn attacks by demons and

spiritual doubt? The poem remains vague on this point, mixing instead

images of eros and spiritual terror. For our Rhineland harper, this

would have been an exotic, "foreign" song, something he might have

learned from a travelling minstrel-colleague.

Aurea personet lira (CC 10)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

The nightingale (Latin: philomela)

is the quintessential creature of the hours before dawn, warning

lovers, consoling the lonely and vexing the sleepless. Here, the song of

this little warbler is praised extravagantly and found to be better

than all the instruments of man. Although the earliest extant musical

source (sung here) is a sequence first notated in the 12hc century, we

find the text in numerous older sources, including the songbook of the

Rhineland harper.

III. DESIRE AND SEDUCTION

Many

lyrics survive from 11th-century sources which attest to the powerful

influence on medieval poets and singers of the Song of Songs' dreamlike,

erotic language. There are songs of almost transcendental desire - both

feminine and masculine - but also simple, almost farcical lyrics of

seduction; and we shouldn't be surprised to find all these delicacies

spread by the harper before an appreciative audience of both secular

cognoscenti and learned churchmen.

lam, dulcis arnica, venito (CC 27)

(Aquitaine, late 10c)

This

is one of the most celebrated lyrics in medieval Latin to have

survived. It exists in two versions, one of which stresses the dramatic

tension of the erotic situation, while the other dwells on the almost

sacred, dreamlike nature of the love-dialogue, mirroring the Song of

Songs.The version sung here is what Peter Dronke calls "the seducer's

version", and contains stanzas which are missing from the harper's

collection.

Advertite, omnes populi (CC 14)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

Story-telling

was an important part of the harper's art, and here, in the "Story of

the Snow-Child", we even have a miniature farce, complete with a

sarcastic narrator and a deceitful married couple from Swabia (of

course, if the harper had been Swabian, the nasty couple would have

probably been from the Rhineland).

O admirabile Veneris idolum (CC 48)

(Northern Italy, 11c)

This

poem has been the subject of much discussion over the years: is it a

heterosexual song of desire, sung by a woman, or is it the song of an

older man lamenting that his young male lover has been seduced by a

rival (a genre known in antiquity as paidikon)? We cannot know

for sure, and since the gender situation is vague the singer must embody

both possibilities. Although it is found in the Canterbury manuscript,

we do know that the poem has its origins in northern Italy, near Verona,

that its fame spread to Germanic lands, and that the melody (one of the

oldest decipherable secular melodies) is the same as that of the sacred

pilgrims' song, "O Roma nobilis".

Puella turbata

(Frankish, 10c)

Here,

we reconstruct what could have been an instrumental tradition of

minstrels from the Rhineland with their rendering of an ancient Frankish

melody, a piece entitled Puella turbata ("the troubled girl") which

lived on as a sequence by Notker of St. Gall. We will never learn who

the girl was - although it's probably not difficult to guess why she was

troubled -, but we do know the power that this melody had over the

centuries, both within the church and outside it.

Suavissima nunna (CC 28)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

An

amorous dialogue between a seducer and a nun, in which the participants

begin each line singing in Latin and then switch to German, making for a

hilarious and chaotic swirl of erotic confusion. A prudish medieval

censor was fairly successful in effacing this song (and other naughty

lyrics, including the one which follows on this recording) from the

manuscript, but thanks to the efforts of Peter Dronke, a reconstruction

has been made possible.

Veni, dilectissime (CC 49)

(Rhineland, early 11c)

Emerging from beneath the monastic censor's black ink, this is probably the oldest surviving erotic dance-song in Latin.

SEQUENTIA

Founded

in 1977 by Benjamin Bagby and the late Barbara Thornton, Sequentia is

among the world's most respected and innovative ensembles for medieval

music. Under the direction of Benjamin Bagby, Sequentia can look back on

more than a quarter-century of international concert tours and the

creation of over sixty concert programs that encompass the entire

spectrum of medieval music, in addition to the realization of

music-theater projects such as Hildegard von Bingen's Ordo Virtutum, the Cividale Planctus Marie, the Bordesholmer Marienklage, and Heinrich von Meissen's Frauenleich.

In addition to these performance activities, the ensemble has produced a

comprehensive discography spanning the entire Middle Ages (including

the complete works of Hildegard von Bingen), film and television

productions of concerts and medieval music drama, and has developed

professional courses to train a new generation of young performers.

Sequentia has performed throughout Europe, the Americas, the Middle

East, India, Asia, Africa and Australia, and has received numerous

prizes (including a Disque d'Or, several Diapasons d'Or, the CHOC, two

Edison Prizes, the Deutsche Schallplattenpreis and a Grammy nomination)

for many of its more than 20 recordings on the Deutsche Harmonia Mundi

label. In 2002, Sequentia released an acclaimed 2-CD set of stories from

the medieval Icelandic Edda: The Rheingold Curse, on the Marc Aurel

Edition label. Since 2003, the ensemble records exclusively for the BMG

Classics / DHM label. The work of the ensemble is divided between a

small touring ensemble of vocal and instrumental soloists, and a larger

ensemble of voices for the performance of chant and polyphony. After 25

years based in Cologne, Germany, Sequentia's home is now in Paris (www.sequentia.org).

Vocalist, harper and scholar Benjamin Bagby

has been an important figure in the field of medieval musical

performance for over 20 years. Since 1977 he has devoted himself almost

entirely to the work of Sequentia. As a soloist, Benjamin Bagby devotes

his time to the performance of Anglo-Saxon and Old-Icelandic epic poetry

(including an acclaimed bardic performance of the Beowulf epic).

He writes frequently about performance practice, and has been a guest

lecturer and professor, teaching courses and workshops in Europe and

North America.

Agnethe Christensen, originally from

Sweden, studied at the Royal Danish Conservatory, later specialized in

renaissance and medieval singing with Andrea von Ramm in Basel, with

subsequent studies in Rome and Paris. Well-known for her unconventional

interpretations of modern and classical works, she represents the recent

wave of, and exploratory marriage between, contemporary, folk and early

vocal music. Ms. Christensen has worked with composers such as Wolfgang

Rihm, Luciano Berio, Palle Mikkelborg and John Cage; with opera, folk

and film music; with baroque music together with Frieder Bernius,

Reinhard Goebel and Concerto Copenhagen; and with her regular medieval

music group, Alba, with which she has released several CDs. She also

appears on opera stages worldwide performing mainly modern and baroque

opera, most recently in the Danish performance ensemble Hotel Proforma's

production of Operation Orfeo.

Eric Mentzel was

born in Philadelphia and studied voice and organ at Temple University

before taking a Masters Degree in early music performance practice at

Sarah Lawrence College in New York. He began his career in New York as a

soloist specializing in early music, appearing with such renowned

ensembles as Pomerium and the Schola Antiqua. Since moving to Germany in

1988, Eric Mentzel has appeared throughout Europe, North America and

Asia as a member of Sequentia, the Huelgas Ensemble, the Ferrara

Ensemble, and as an oratorio soloist in addition to participating in

more than 40 CD recordings and numerous radio and television

productions. He has also appeared in contemporary opera productions in

Germany, and is in demand as a teacher of early vocal style and

techniques, teaching at the Schola Cantorum in Basel, Sequentia's

Medieval Music Programme in Vancouver, and the Mannheim Musikhochschule.

He is currently on the voice faculty of the University of Oregon School

of Music (USA).

Norbert Rodenkirchen was born in Cologne,

where he studied both modern and baroque flute at the Hochschule für

Musik. He is in demand as a performer and composer in the realms of new

music, early music, theater and film music.

Mr. Rodenkirchen is

especially interested in the shared characteristics of much contemporary

music with music from the Middle Ages. He has been musical director of

theater productions at the Staatstheater Darmstadt, the Schauspiel

Wuppertal and Stadttheater Bremen, has composed works for Radio Bremen

and the West German Radio, and has appeared internationally as a

flautist and recording artist. In 1998, together with vocalist Maria

Jonas, he founded the early music ensemble Diphona. His first solo CD, Tibia ex Tempore, was released on the Marc Aurel Edition label in 2001.