medieval.org

sequentia.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 8 87654 68642 8

2013

1. O splendidissima gemma [10:21]

V fol. 154 · antiphon, to Maria / with canticum: Magnificat anima mea dominum

Lena Susanne Norin, ensemble

2. O dulcis electe [4:34]

V fol. 161v · responsory, to St. John the Evangelist

Sabine Lutzenberger, ensemble

3. O speculum columbe [7:34]

V 161v · antiphon, to St. John the Evangelist / with Gloria patri

Lydia Brotherton, with Norbert Rodenkirchen flute, ensemble

4. O spectabiles viri [5:34]

V fol. 159v · antiphon, to the Patriarchs and Prophets

Christine Mothes, ensemble

5. O cohors milicie floris [13:45]

V fol. 160v · antiphon, to the Apostles

with canticum: Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel

Agnethe Christensen, ensemble

6. O victoriosissimi triumphatores [8:29]

V fol. 163 · antiphon, to the Martyrs / with: Gloria patri

Lena Susanne Norin, with Benjamin Bagby harp, ensemble

7. Kyrieleison [3:13]

R fol. 472v

Esther Labourdette, ensemble

8. O vos imitatores excelse [4:23]

V fol. 163v · responsory, to the Confessors

Sabine Lutzenberger, ensemble

9. O gloriosissimi lux [5:12]

V fol. 159 · antiphon, to the Angels

Elodie Mourot, ensemble

10. O vos angeli [8:40]

V fol. 159 · responsory, to the Angels

Lena Susanne Norin, Sabine Lutzenberger, Agnethe Christensen (verse),

Lydia Brotherton, Norbert Rodenkirchen flute, ensemble.

The Sequentia women's vocal ensemble:

Lydia Brotherton

Agnethe Christensen

Esther Labourdette

Sabine Lutzenberger

Christine Mothes

Elodie Mourot

Lena Susanne Norin

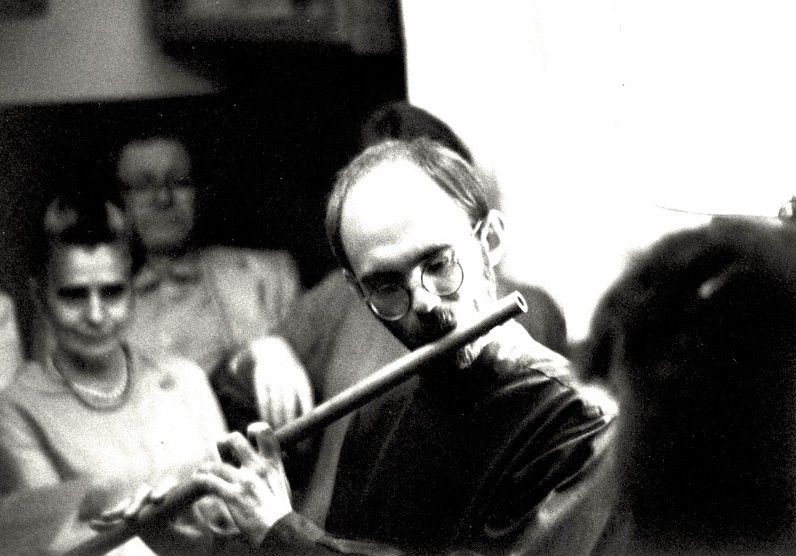

Instrumentalists:

Norbert Rodenkirchen, flutes

Benjamin Babby, harp

SEQUENTIA, Ensemble for medieval music

BENJAMIN BAGBY, director

Sources:

All performing editions were prepared by Benjamin Bagby and are based on the manuscript V:

Dendermonde (Belgium), St. Pieter Et Paulusabdij Codex Afflighemiensis 9 (Rupertsberg, ca. 1170).

The Kyrieleison (track 7) and some minor corrections are from the manuscript R: Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek, Hs. 2 ('Riesenkodex'). One small correction in O vos imitatores (track 8) is taken from Z: Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Codex theol. phil. 4° 253 (fol. 40v).

Instruments:

- transverse flute (track 3) by S. Silverstein (New York City, 1980)

Note: this instrument once belonged to David Hart (1951-1988) who played it in the first two Sequentia recordings of Hildegard's music.

In 2012 the flute was given to Norbert Rodenkirchen by David's brother Jim Hart, and is played here again, 30 years later.

- 15-string harp (track 6) by Geoff Ralph (London, 1983)

- transverse flute (track 10) by Neidhart Bousset (Berlin, 1998)

Recording: November 11-15, 2012, Church of Saint Remigius, Franc-Waret, Belgium

Recording Producer and Engineer: Nicolas Bartholomée · Assistant Engineer: Maximilien Ciup

Production Assistance: Norbert Rodenkirchen · Associate Producer: Matthias Spindler. Executive Producer: Jon Aaron

Front cover: The angelic choirs, from Hildegard's Scivias, Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek Hs. 1

(lost after 1945), 20th-century parchment copy from the Abtei St. Hildegard, Eibingen (Germany); akg-images / Erich Lessing

Artwork: www.waps.net

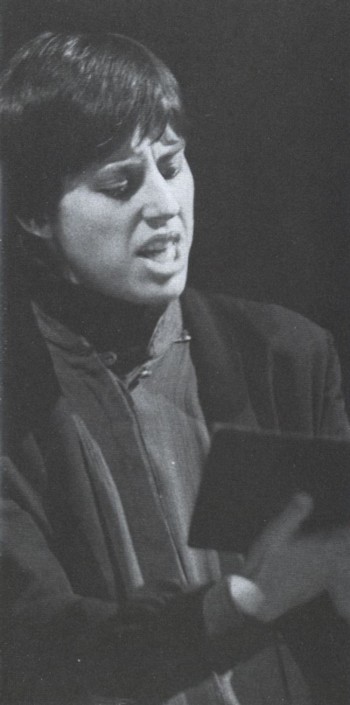

in memoriam

BARBARA THORNTON (1950-1998)

THE HEAVENLY HIERARCHY, OR RAYS OF LIGHT

Mention the word "hierarchy" today, and very few people will respond

positively to it, for we tend to think, rather, of fossilized power

structures, of individuals straying into areas outside their field of

competence and of attempts to muzzle those who think differently. It

may be even harder for us to grasp the concept of a heavenly hierarchy

as we are likely to suspect that we are dealing here with the same

defective forms and at the same time that there is no possibility of

resisting them.

Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) thought very differently. If she saw

the saints and angels as an effective part of otherworldly reality, it

was because she sensed that they supported her through a network whose

scope for action far exceeded her own. And so she did what anyone would

have done who wants to achieve something and who is in full possession

of all their senses: she sought support from those people who had led

exemplary lives and who were now in the Kingdom of Heaven or, in the

case of the angels, had dwelt with God since the dawn of Creation.

SAINTS IN THE BACKGROUND

The present release is the last in the series of Sequentia's set of

recordings of music by the medieval female composer Hildegard von

Bingen and is devoted to her hymns not only to the angels but also to

the patriarchs and prophets, the apostles, martyrs, confessors, John

the Evangelist and Mary the Mother of Jesus. Hildegard felt very close

to each and every one of them, their exemplary lives encouraging her to

continue on her own often difficult and painful journey through life.

Two instances may illustrate this point. The patriarch Abraham left his

home city of Ur of the Chaldees in order to embrace an uncertain

future. In much the same way, Hildegard left the protection of the

convent at Disibodenberg to live in the wilderness of Rupertsberg far

from human comforts and achieve her dream of self-determination. The

Virgin Mary was Hildegard's point of departure in developing her own

particular brand of theology, with its support for women and for human

dignity in general, an outlook that shielded the women of her convent

from the commonplaces of the theological mainstream, which saw them as

the source of all evil.

For Hildegard, every spiritual journey began with repentance, a

world-changing force that found expression in a sigh. By "repentance"

she meant the anguish felt when we are untrue to our innermost nature.

In the case of the present recording, this aspect of Hildegard's world

view is represented by the Kyrie eleison ("Lord, have mercy

upon us"), which is an appeal to God's helping power and at the same

time a hymn in celebration of that power. Its roots can be traced back

to the Hellenistic period.

In Hildegard's eyes, praising God was one of those activities that

allow us as individuals to reconnect with our origins, when the world

was still a place of unspoilt innocence. When singing God's praises, we

too take our place in Creation and achieve a state of self-realization.

The interpretation of Creation as a musical event in which the world

comes into existence through singing and is shaped by musical sounds is

one that is found in many religions. According to Hildegard's view of

theology, the literally shining example of this creative music-making

takes the form of the angels, those beings of light whose principal

task is to praise God. All human singing takes their musical existence

as its starting point. When we add our voices to the eternal choir of

angels, we invest our lives with a whole new perspective, thinking and

acting in ways that literally transcend our limited human existence. lt

is no accident that Hildegard's responsory O vos angeli seems

to reflect the distance between heaven and earth with a range that

extends over two and a half octaves. Light and sound are closely

related phenomena, and the idea of a cosmos resounding with music is

one that was bound to appeal to the visionary Hildegard, whose visions

included not only the visible reality of God but also His musical

reality.

As Hildegard puts it in her antiphon O spectabiles viri, the

veneration of the saints begins with the patriarchs and prophets of the

Old Testament who, like her, saw the living light for themselves. (In

advancing this view, Hildegard was not only on firm theological ground

but was also documenting her own understanding of the matter.) On their

way to being examined prior to their acceptance into the tenth choir of

angels, which, as Hildegard says, human beings are called upon to form,

these ancient saints, in which the light took root, are expert

precursors preparing the journey for those who are destined to follow

them. They are succeeded by the apostles as symbolic representatives of

the twelve tribes of Israel, who herald the age of the New Testament.

In the early Church, the injunction "Be ye holy, for I am holy" applied

as a matter of course to all Christians. For Hildegard, sanctity was

above all a question of wholeness, which in terms of her own

theological outlook could mean only to be in harmony with the positive

forces of the cosmos, a harmony that in music is the equivalent of

consonance. Among those who were venerated as saints, pride of place

goes to those who died for their faith. It is to them that Hildegard

dedicated her antiphon O victoriosissimi triumphatores. Next to

the martyrs it was the confessors who were revered as saints, men and

women who attested to the truth of the Word that Christ had addressed

to them and that He Himself embodied. Hildegard honours them with her

responsory O vos imitatores excelse. In her theology, Mary and

John represent a direct link with God and His son, Jesus Christ. John

is believed to be the disciple whom Jesus loved above all others and

who remained at His side at the Last Supper. The extent to which

Hildegard identified with John is clear from a vision - arguably her

most personal - in which she herself takes his place. This connection

between the Benedictine abbess and the disciple is particularly clear

in the responsory O dulcis electe. In it she describes John as

someone who comforts the "pigmentarii", an old word that literally

means "perfumers" or "salve mixers", in other words, bishops who are

meant to be the source of viriditas, the viridescent, healing

life force that floods the whole of the cosmos.

Mary is undoubtedly Hildegard's favourite female saint, and the

antiphon O splendidissima gemma is a fine example of her

spirituality, a spirituality that links earth and heaven and that

encapsulates the poet's fascination with gemstones, which she regarded

as tangible relics of Paradise, allowing her to put into words her love

of the Virgin Mary and to clothe that love in a complex musical form. O

splendidissima gemma has been re-recorded for the present album, as

the earlier recording from 1982, in which it featured as part of the

morality play Ordo Virtutum, is no longer commercially

available.

WHY LESS IS MORE AND WHY FAITH IS NOT A SHORTCOMING

WHY LESS IS MORE AND WHY FAITH IS NOT A SHORTCOMING

A comparison between the present release and earlier Sequentia

recordings reveals that in the present case the instrumental

accompaniment is markedly sparer, although this does not mean that

instruments were not used in Hildegard's day. Her biographer and

secretary Guibert of Gembloux mentions that her works were performed

using instruments, and she herself thought highly of flutes, harps and

other instruments, as is clear from her magnificent letter to the

prelates of Mainz in which she describes the function of music, even

identifying various human characteristics with different bodies of

sound. But there are good reasons to use instruments more sparingly

than was customary in the 1990s and to deploy them above all in the

solo antiphons, which are particularly intimate in expression. At the

same time, they may be used to lend a sense of stability to large-scale

structures such as O vos angeli. Hildegard's songs are not

examples of art music that are at home onstage and that can be arranged

in effective ways depending on the performers' inspiration and wealth

of ideas. The longer the ensemble has worked on this music and examined

the research that has been conducted on it, the more it has become

clear that we are dealing here with music for the liturgy. If we take

this idea seriously, then we shall find that our basic attitude to the

way that this music is sung and played is bound to change. Even though

we live in an age in which faith is no longer a subject of discussion

for many people, we cannot assume that this was the case in the twelfth

century. Hildegard's music is inspired by the liturgy and written for

it. If we take this into account, these works gain in focus and

radiance, qualities necessary if we are to penetrate to their core.

The same is true of their notation. In the twelfth century neumatic

notation was characterized by a different approach to the notes from

that found in earlier manuscripts. And this certainly applies to

Hildegard's compositions, which are influenced in turn by the vocal

tradition of the Rhineland. The technique that she used in adapting the

versus melodies affords impressive evidence of the care she

lavished on the word-tone relationship, while her use of liquescent

neumes for semantic purposes points to the rhythmic information

contained in the neumatic notation of late Gregorian chant both in her

own compositions and in those of a number of her contemporaries. If we

take this seriously, the texts and their living declamation again

become the focus of attention, and the melodies are taken seriously as

a way of deepening and interpreting the textual message. This is

perhaps their principal advance on equal or mensural interpretation.

Taking account of the contextuality of Hildegard's settings, Benjamin

Bagby and his ensemble have deliberately combined a number of them with

a Gloria Patri, a Magnificat and a Benedictus,

since these antiphons were intended to be used during the canticles at

lauds and vespers. It is merely because of the limits on the time

available that not all the songs have been combined with Psalm verses

and a Gloria Patri. As the basis of its recording the ensemble

used the Dendermonde Codex, which dates from around 1170 and is the

older of the two manuscripts preserving Hildegard's songs. The later

Kyrie is taken from the so-called Riesenkodex. I am

particularly delighted at this release as it provides a magnificent

conclusion to Sequentia's pioneering complete recording. And I am no

less grateful for my long and invariably inspiring contact with

Benjamin Bagby and the unforgotten Barbara Thornton, whose ideas,

profound musicality, expertise and enthusiasm substantially enriched my

own work on these pieces.

Translation: Stewart Spencer

THE HILDEGARD VON BINGEN PROJECT (1982-2012)

Since the early 1980's, the ensemble Sequentia's name has been closely

linked with the music of Hildegard von Bingen, the visionary abbess

whose musical compositions are among the most astonishing and unique

creations from the dynamic milieu of 12th-century Benedictine

monasticism. Under the general artistic direction of the late Barbara

Thornton, many of the world's foremost vocalists and instrumentalists

active in historical music performance joined Sequentia to perform and

record Hildegard's works on a regular basis between 1982 and 1999, and

again under Benjamin Bagby's direction in 2012.

In 2012 this final recording of the complete works, Celestial

Hierarchy was brought to life by Sequentia's co-founder and

director Benjamin Bagby to commemorate the elevation of Hildegard von

Bingen to Sainthood and Doctor Ecclesiae (2012), to finish Sequentia's

complete works project on the DHM label, and thus to honour the life's

work of Barbara Thornton. For this recording, a multi-generational

ensemble of seven women's voices has been assembled under Bagby's

direction, together with the flautist Norbert Rodenkirchen and Bagby

playing harp. One of the singers on this final recording had been a

member of Barbara Thornton's ensemble, while some others were not yet

born when the first recording was made in 1982.

THANKS

to HERMAN BAETEN (Musica, Belgium) for the facsimiles of the

Dendermonde manuscript (Alamire publishers) generously given to each

musician involved in this project.

to MARIE NOEL COLETTE for stimulating discussions about 12th-century

chant notation, especially the quilisma.

to JIM HART for the gift of David Hart's flute, used here in track 3.

to LAURENCE MOULINIER for permission to use her French translations of

Hildegard's texts.

to KATARINA LIVLJANIC for providing the psalm-tones and cantica-tones

used in this recording.

to LAWRENCE ROSENWALD for his new English translations of Hildegard's

texts.

to BARBARA STÜHLMEYER for permission to use her German

translations of Hildegard's texts and for her many years of support of

the ensemble's Hildegard project.