Zachara, cantore dell'antipapa (secolo XV)

Sine Nomine, on historic instruments

medieval.org

Quadrivium SCA 027

1995

1. Credo [7:54] Varsavia, Bibl. Nadorova, ms. III, 8054

voci GM AF, bombarda MF, tromba a tiro PC, viella BH

2. Dime, Fortuna [3:23] Torino, ms. Boverio · opus dubium

voci GM AF

3. Rosetta che non cangi mai colore [4:16] codice Mancini

ciaramella MF; tromba a tiro PC; naccari SP

4. Cacciando per gustar ~ Ai cenci! Ai toppi! [4:56] codice Squarcialupi

voci GM AF SP, viella BH

5. Movit'a pietade [4:53] codice Squarcialupi

canto GM, liuto FT

6. Ciaramella [2:50] codice Mancini

flauto da tamburo FT, ciaramella MF, tromba a tiro PC, rullante SP

7. Ferito già d'un amoroso dardo [3:32] codice Squarcialupi

voci AF SP

8. Deus deorum Pluto [6:30] codice Mancini

voci AF DB, viella FT

9. Movit'a pietade [3:21] codice Squarcialupi

flauto doppio MF

10. E ardo in un fuogo [4:36] Strasburgo, Stadtbibl. 222

voci AF SP, vielle FT BH

11. Je suis navrés ~ Do quoy ~ Gnaff'a le guagnele [3:33] codice Mancini

voci AF SP DB, vielle FT BH

12. Un fior gentile [3:40] Faenza, Bibl. Comunale, ms. 117

liuto FT, viella BH

13. Plorans ploravi perché la Fortuna [7:55] codice Mancini

voci GM AF

14. Ciaramella mè dolze [3:57] codice Mancini

voci GM AF SP, bombarda MF, tromba a tiro PC; viella BH; tammorra FT

fonti:

Varsavia, Bibl. Nadorova, ms. III, 8054 (1)

Torino, Bibi. Nazionale, ms. Boverio (2)

Lucca, Archivio di Stato, ms. 184, codice Mancini (3, 6, 8, 11, 13, 14)

Firenze, Bibl. Mediceo-Laurenziana, Pal. 87, codice Squarcialupi (4, 5, 7, 9)

Strasburgo, Stadtbibl. 222 (10)

Faenza, Bibl. Comunale, ms. 117 (12)

SINE NOMINE

Alessandra Fiori — voce

Gloria Moretti — voce

Stefano Pilati — voce, percussione (naccari, rullante)

Decio Biavati — voce

Marco Ferrari — flauto doppio, bombarda, ciaramella

Bettina Hoffmann — viella

Fabio Tricomi — viella, liuto, flauto di tamburo, percussione (tammorra)

Pier G. Callegari — tromba a tiro

Registrazione

Digitale: Studio Audio SCA

Tecnico del suono: Francesco Ciarfuglia

Ingegnere del suono: Riccardo Magni

Direttore di produzione: Carlo

Pedini

Registrazioni efrettuate a Perugia, Tempio di Sant'Angelo

nel mese di Agosto 1992

QUADRIVIUM - Edizioni Discografiche 1995 ©

Perugia

Note critiche a cura di Alessandra Fiori

Zachara, cantore dell'antipapa

Eccentrico, ribelle,

assolutamente geniale, Antonio di Berardo da Teramo detto "Zachara"

rappresenta, alla luce delle più recenti scoperte musicologiche, una del

le figure maggiormente significative del Medioevo italiano. La sua

produzione ha carattere fortemente eterogeneo: ballate di tipica fattura

arsnovistica, cacce (purtroppo ne è rimasta solo una, Cacciando per gustar),

brani di impronta schiettamente popolareggiante, composizioni nei

canoni stilistici del linguaggio musicale più in iniziatico e involuto

del momento (la cosiddetta ars subtilior); infine una consistente

quantità di brani liturgici. Ciò che rende la figura di Zachara

assolutamente originale, e che ci fa apprezzare, oltre al compositore

anche l'individuo in tutte le sue sfaccettature, è il fatto, abbastanza

curioso per il periodo, che le sue composizioni siano per lo più a

carattere autobiografico, rendendo in qualche modo conto dei turbamenti e

delle contraddizioni di un uomo di chiesa un po' troppo attratto, come

spesso allora accadeva, dal le lusinghe del secolo. Tutti i suoi brani

ci danno l'immagine di un artista che, pur distinguendosi per un modo di

comporre assolutamente personale e inconfondibile. abbraccia tutti gli

stili, sperimenta soluzioni musicali ardite e innovative per quel tempo,

anticipando alcuni tratti dell'espressione frottolistica di fine

Quattrocento.

Siamo lieti di ospitare, all 'interno di questo

nostro CD, il contributo di uno studioso ed amico - John Nádas,

professore all'Università di Chapel Hill- N. Carolina - U.S.A.), che,

oltre ad avere, qui, gentilmente illustrato lo stato attuale delle sue

ricerche sulla vita di Zachara, è sempre stato fonte di preziosi

consigli nel percorso intrapreso dal nostro gruppo.

Alessandra Fiori

Zachara, cantor of the Antipope

Eccentric,

rebellious, gifted, Antonio di Berardo da Teramo, called "Zachara", is,

according to the latest musicological discoveries, one of the most

important figures of the Italian Middle Ages. His production is

heterogeneous: it consists of ballatas in typical Ars nova style, caccias (unfortunately only one of them, "Cacciando per gustar", has survived), pieces showing popular influence, works in the most complex style of the time (the so-called "ars subtilior");

and lastly, a great deal of liturgical works. That which makes Zachara

unique, and for which we appreciate him today, both as a composer and as

a man, is the fact, unusual for his time, that his compositions have

something of an autobiographical nature, testifying to the anxiety and

contradictions felt by a man of the church who was a little too

attracted by worldly success. All his works reflect the image of an

artist who, while distinguished by an entirely personal and unmistakable

style of composition, experimented with bold and innovatory musical

forms, anticipating some aspects of the late fifteenth century frottola

style.

We are glad to enclose in this booklet the contribution by a scholar and friend - John Nádas,

professor at Chapel Hill University - N. Carolina - USA), who, in

addition to explaining here the present state of his researches about

Zachara's life, has given us valuable advice for the development of our

work.

Antonio "Zachara" da Teramo

It

is fitting that this compact disk mark the first time the compositions

of Antonio Zacara da Teramo receive serious consideration from modern

performers, for no other italian composer active during the period of

the Great Schism (1378-1417) has so captured scholarly attention as has

he, both in the astonishing quality and the surprising quantity of works

to emerge from research efforts of the past two decades (Nino Pirrotta,

Agostino Ziino; more recent Roman archival work by Anna Esposito, and

by the present writer together with Giuliano Di Bacco). Various, but

sometimes similar or nearly identical, attributions in the widely

dispersed surviving musical manuscript sources at one time had been

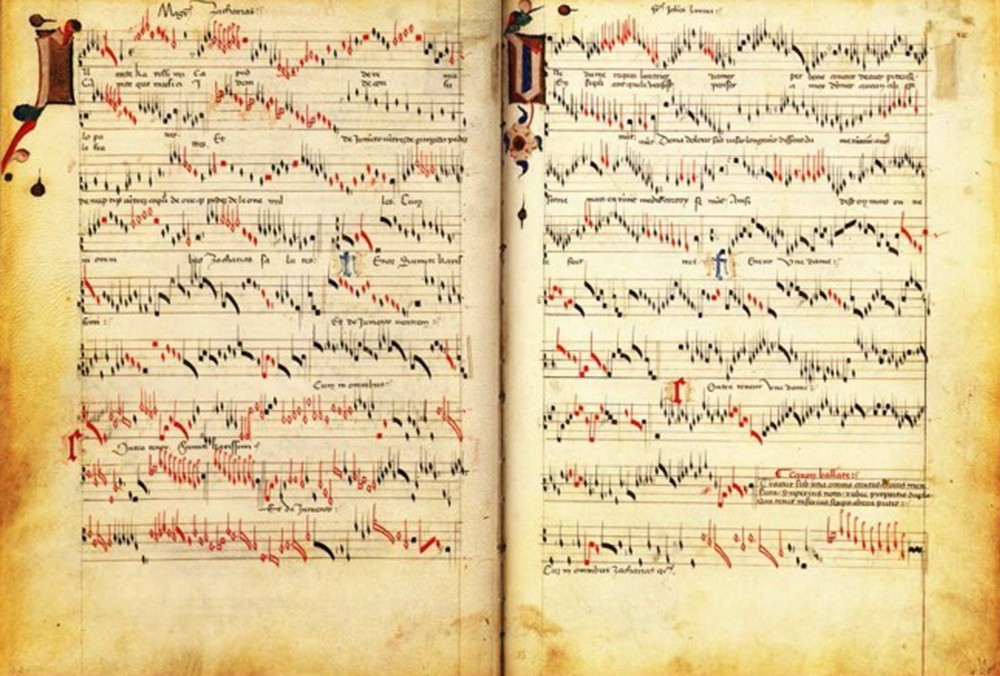

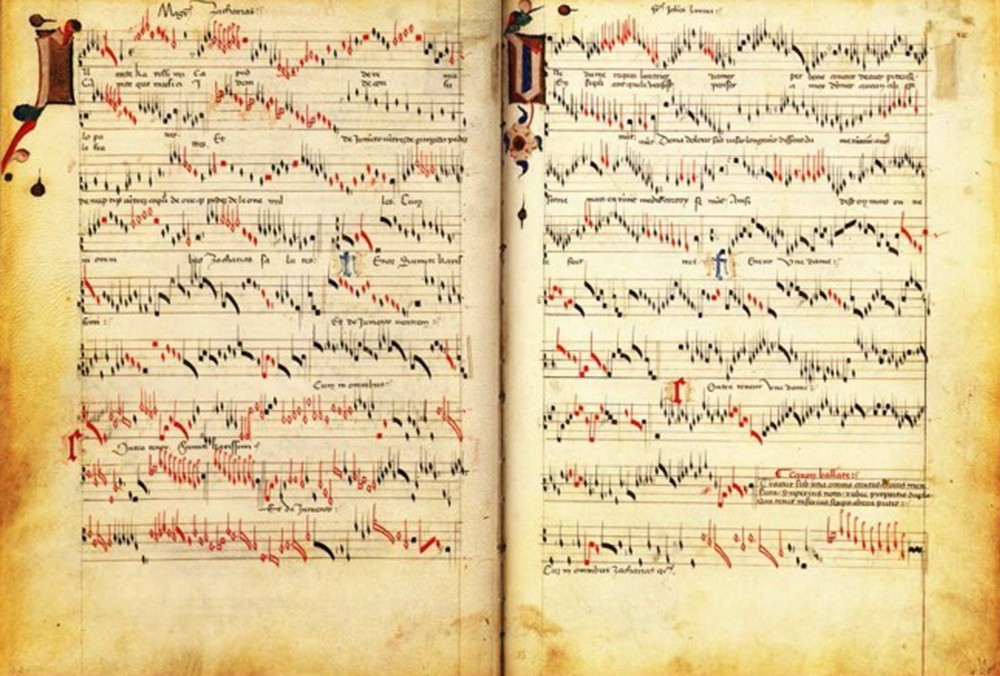

accepted as references to as many as three distinct composers: "Antonius dictus Zacharias de Teramo", "MagisterZacharias", and "Magister Çacherias cantordomini nostri pape", this last the author of a group of songs in the renowned Squarcialupi

Codex from Florence of ca. 1415. It is now clear, however, that the

entire corpus works attributed to assorted forms of the name "Zacara"

- with the exception of three pieces ascribed to Nicolaus Zacharie of

Brindisi - is the accomplishment of one man: a native Italian who may be

compared with his better known and younger contemporary working in

Italy, Johannes Ciconia (ca. 1365-1412), a figure now central to our

understanding of Italian secular and sacred music at the end of the

Fourteenth-century and the early years of the Quattrocento. That he was

already acclaimed as a significant international figure in a

15th-century document is noteworthy, praised by one of his own

countrymen as the author of many compositions "which in our time are

sung in Italy and held in the highest regard by French and German

singers." The more unusual information in that document concerns the

physical description of the composer: "he was short of stature and had

no more than ten digits between his hands and toes, although he could

write elegantly":

Zaccarias Teramnensis, vir apprime doctus in

musicis, composuit quamplures cantilenas, quae nostra aetrate per

Italiam cantatur, et Gallis et Germanis cantoribus in maxima veneratione

habentur: fuit statura corporis parva, et in manibus et pedibus non

nisi decem digitos habuit, et tamen eleganter scribebat. In curia Romana

principatum obtinens magna stipendia meruit

One thus learns

from his full name that Antonio hailed from the city of Teramo in the

Italian Marche. Of some interest is the appearance of the phrase "dictus Zacharias" as part of his name both in formal documents and in musical ascriptions; this had led to a consideration of "Zacara" not as a family name, but rather as a descriptive name - a sobriquet -. This appellative seems to derive from the Biblical Zaccheus,

the chief publican and tax collector in Luke, chapter 19, verses 1-10,

who wishing to view Jesus entering the city of Jericho, but unable to do

so because he was so short of stature, climbed a sycamore tree to see

over the head of the crowd. If Antonio da Teramo's documented diminutive

size was a basis for a nickname (cf. the eulogy, above), then surely

here was the origin of the sobriquet "Zacharias" or "Zacara". The portrait of "Magister Çacherias cantor domini nostre pape" in the Squarcialupi

Codex (seen in the reproduction on the cover page of this CD) helps to

confirm the physically crippling features of its subject: Antonio

clearly lacks several fingers on each of his hands, his left arm appears

to be held in some sort of sling, and his left foot is malformed.

Antonio Zacara da Teramo is documented, primarily in Vatican registers,

as having served successive popes from Boniface IX to John XXIII, the

pope from the period of three-fold schism with close Florentine

connections and to whom the composer's full name in the Squarcialupi

Codex refers. That is, Antonio was in papal service, much of the time both as a singer (capellanus et cantor capelle pape) and scribe (scriptor

litterarum apostolicarum), from at least 1 February 1391 to the summer

1413 (he can now be shown to have died sometimes between May 1413 and

September 1416).

A recently discovered archival document in fact

pushes back Antonio's Roman residence by at least one year to 5 January

1390, and provides an amazing glimpse of his esteem within cultural

circles of the eternal city: "Magister Antonius Berardi Andree de Teramo alias dicto vulgariter Zacchara"

an excellent, expert, and famous singer, had been commissioned by the

Ospedale of Santo Spirito in Saxia (near St. Peter's) to produce a new

antiphoner, for which Antonio will execute the text, music, and

decoration of the book. His reputation and maturity of age in 1390 as

implied by this document would suggest that his apprenticeships as

musician dates from the early years of the schism and was formed through

contacts with both native and foreign musicians in Rome. As part of his

payment in 1390, for the next three years Antonio was to receive use of

a house located next to the parish church of Santa Maria de Monte

(Monte Giordano), in the area of Rome known as "Ponte" (directly across

the river from Castel Sant'Angelo). It is this residence, together with a

suggested connection to one of the most influential families of the

city, the Miccinelli, that ties several of his sacred and secular works

to Rome of the 1390s (e.g., his Gloria "Micinella" and Credo "Cursor").

Moreover,

a professional relationship between Antonio da Teramo and fellow

composer Johannes Ciconia may be surmised in that both can now be

associated with cultural circles and the musical chapel of Cardinal

Philippe d'Alençon at his titular church of Santa Maria in Trastevere

during the 1390s. Indeed, a number of stylistic affinities may be found

in their Mass movements and, especially, in their Italian song settings.

It

was in Rome that the music of the two leading composers of the period

must have entered and circulated with the repertory of the papal chapel,

given the contents of a number of sources believed to transmit Roman

works of the 1390s and early 1400s, and the dissemination of this music

to important cities of papal residence and to widely dispersed

institutions via musicians in contact with the schismatic papal chapels

and the early 15th-century church councils (Pisa in 1409 and Constance

in 1414-1418). His more than twenty surviving sacred works and some two

dozen songs were copied, and some recopied, during his lifetime and

shortly after in outstanding collections of music, among them the Mancini Codex and the newly discovered Boverio

manuscript of the Turin National Library; thus, Antonio da Teramo's

music was known throughout the Italian peninsula and as far away as

England, Germany, Austria, and Poland.

John L. Nádas

1. Credo (Varsavia, Bibl. Nadorova, ms. III, 8054)

Voci: GM, AF, SP; bombarda: MF; tromba a tiro: PC; viella BH.

Voices: GM, AF, SP; shawm: MF; slide trumpet: PC; fiddle: BH.

La

produzione di Zachara comprende molte opere sacre, caratteristiche per

il fatto di essere state create, molto spesso, rielaborando ed ampliando

il materiale tematico dei brani profani dello stesso autore. Avremo,

pertanto, il Gloria Rosetta, Fior gentil, il Credo Deus Deorum,

ecc. (una sorta di anticipazione della forma parodia, in voga alcuni

decenni più tardi); a tutt'oggi non è stato comunque possibile trovare

un brano al quale ricondurre il Credo di Varsavia (ed un Gloria, cui questo potrebbe essere stato appaiato). Questo Credo,

unico nel suo genere, si distingue, inoltre, per avere la voce

superiore frequentemente sdoppiata in due soluzioni melodiche differenti

ed inserti a due voci sole sulle parti del testo più significative, cui

segue, in genere, la ripresa del tema principale. La strumentazione

scelta in questo caso si rifà a quella adottata nelle festività solenni

che, anche all'interno delle chiese, prevedeva spesso l'uso di strumenti

a fiato, da soli o abbinati alle voci.

Zachara's

works include many sacred pieces which are notable for their reworking

and amplifying of thematic material taken from his own secular

compositions. "Gloria Rosetta", "Fior gentil", "Credo Deus deorum"

(a kind of anticipation of the parody-form, fashionable some decades

later), are examples of this technique. Until now a source for the

Warsaw "Credo" (and of a "Gloria", perhaps coupled with

it) has not been found. This "Credo", unique of its kind, stands out

because the upper voice is frequently divided between two different

melodies, and has sections for two voices alone on the most significant

parts of the text, usually followed by the repetition of the main

theme. The instrumentation chosen for this work derives from that used

for solemn ceremonies, which, even in churches, frequently used wind

instruments, alone or to accompany voices.

2. Dime, Fortuna (Torino, Bibi. Nazionale, ms. Boverio)

Voci: GM, AF.

Voices: GM, AF.

Dime Fortuna

è una ballata inedita, trovata nel 1991 da Agostino Ziino. Essa

contiene, nel testo, importanti conferme per quanto riguarda la

biografia di Antonio da Teramo e, di conseguenza, la datazione del brano

stesso (dopo il 1410). Si dice qui infatti che la sorte sarebbe

cambiata se Alessandro fosse andato a Roma: si intende forse parlare

dell'antipapa Alessandro V (1409-10), al cui servizio si pose

probabilmente Zachara, e che morì in circostanze misteriose a Bologna,

dopo pochi mesi di pontificato. L'Autore che, come vedremo, è facile

alle lamentele, specie dal lato economico, non esita a mettere in musica

le sue angosce, in un periodo in cui l'autobiografismo in musica era un

fatto abbastanza raro. La costruzione del brano è sobria, con un

declamato stretto e incalzante; si distacca dunque dal modello

trecentesco, che vedeva la voce superiore infarcita di virtuosismi e

quel la bassa relegata ad una mera funzione di sostegno: qui le voci non

solo hanno quasi uguale importanza, ma si muovono persino nella stessa

tessitura, creando un continuo effetto di intreccio, del tutto

sconosciuto alle composizioni del secolo precedente.

"Dime, Fortuna"

is a hitherto unknown ballata, found in 1991 by Agostino Ziino. Its

text includes important information about the life of Antonio da Teramo,

and, as a consequence, the dating of the work itself (after 1410). It

tells us, in fact, that history would have been different had Alessandro

gone to Rome: perhaps the subject was the Antipope Alessandro V

(1409-10), for whom Zachara had worked, and who had died in obscure

circumstances in Bologna, after only a few months of papacy. The author,

who as we can see seems much given to complaining, especially about his

economic circumstances, set his anguish to music in a period in which

autobiographical reflections in music were relatively rare. The

structure of this piece is concise, with rapid and pressing declamation;

it stands apart from the fourteenth century model, in which the upper

part was full of virtuosity and the lower relegated to the role of

accompaniment. Here the voices not only have almost equal importance,

but they also move within the same tessitura, creating a continuous

intertwining effect, unknown in works of the previous century.

3. Rosetta che non cangi mai colore (Lucca, Archivio di Stato, ms. 184, codice Mancini)

Ciaramella: MF; tromba a tiro: PC; naccari: SP.

Shawm: MF; slide trumpet: PC; castanets: SP.

Rosetta, assieme a Ciaramella,

è uno fra i brani in cui maggiormente si ravvisano le influenze della

musica popolare sul nostro Autore. II brano è assolutamente anomalo, per

quell'epoca, basti ascoltare l'inizio, in cui la voce inferiore,

affidata alla tromba a tiro, rimane ferma per molte misure su un pedale

di Fa. Il ritmo ternario, i bordoni ed i frequenti salti di quarta e di

quinta rendono poi evidente che il modello per alcuni passaggi di questa

composizione è dato dal fraseggio della zampogna, come già aveva

giustamente osservato Nino Pirrotta. Proprio per evidenziare queste

peculiarità strutturali, ne è stata data qui una versione per strumenti a

flato.

"Rosetta", together with "Ciaramella", is

one of the works showing an influence of popular music on Zachara. This

composition is absolutely anomalous, for that period, because, at the

beginning, the lower part (played by the slide trumpet) remains

stationary on a F pedal for many measures. The ternary rhythm, the

burdens and the frequent leaps of fourths and fifths show that the model

for some passages in this work derives from phrase-structure

characteristic of the bagpipe, as has already been noticed by Nino

Pirrotta. In this CD a wind instrument version has been chosen in order

to emphasise these structural features.

4. Cacciando per gustar / Ai cenci, ai toppi! (Firenze, Bibl. Mediceo-Laurenziana, Pal. 87, codice Squarcialupi)

Voci: GM, AF, SP; viella: BH.

Voices: GM, AF, SP; fiddle: BH.

Si

tratta sicuramente di uno dei capolavori di Zachara e della musica

medievale italiana in generale. Il risultato sorprendente raggiunto dal

nostro Autore, che mette in luce le sue indubbie capacità compositive,

consiste nel gioco ben strutturato tra le parti superiori: le due voci

femminili dialogano e si intrecciano tra loro, con frasi che rimbalzano

da una voce all'altra e procedimenti di hochetus, il tutto in una

sorta di disordine organizzato. Da evidenziare anche la rispondenza tra

parole e musica: si noterà che il testo non svela immediatamente

l'ambientazione urbana della caccia, anzi, indugia, inizialmente sulla

descrizione di una sorta di locus amcenus ; anche l'esordio

vocale, con un canto disteso e legato, tradisce i successivi sviluppi

del brano. E' il tenor ad interrompere l'idillio iniziale, col grido

irruento di "Ai cenci !Ai toppi!"

e a dare l'avvio al rincorrersi delle voci; così come

serà il tenor ad uscire per primo di scena, con l'esclamazione

allusiva: "Si, madonna, sì, salgo su" , mentre le due voci superiori, rimangono sole a ... tirare le somme del brano ( "chi altro che farina compra, vende; chi dorme, caccia, stuta e chi accende" ) in un perfetto anticlimax che, con movimento di chiusura circolare, va immancabilmente a rapportarsi all'atmosfera iniziale.

This

is definitely one of Zachara's masterpieces, and one of the finest

works of Italian Middle Ages. It shows Zachara's compositional skill in

the well structured effect in the upper parts: the female voices

alternate and intertwine in phrases passing from one voice to another

and in "hochetus", in a kind of "organized disorder". The

relation between text and music is also noteworthy: at the beginning the

text does not reveal the urban setting of the hunt, but rather

describes a kind of "locus amoenus"; the beginning of the music,

too with its relaxed and legato phrasings, is very different from the

following development. It is the tenor who interrupts the opening idyll,

crying out, impetuously: "Ai cenci, ai toppi!", giving rise to the chasing of the voices; and it will be the tenor who will exit first, exclaiming, allusively: "Sì, madonna, si salgo su!", while the upper voices remain alone to conclude the work ("chi altro, chi farina compra, vende; chi dorme, caccia, stuta e chi accende") in a perfect anticlimax that, with a circular closing movement, refers back to the opening atmosphere.

5. Movit'a pietade (Firenze, Bibl. Mediceo-Laurenziana, Pal. 87, codice Squarcialupi)

Canto: GM; liuto: FT.

Voice: GM; lute: FT.

Al codice Squarcialupi

appartengono le composizioni di Zachara che rientrano nello stile

arsnovistico più classico: dobbiamo pensare, dunque, a queste come ad un

prodotto giovanile, nel pieno rispetto della tradizione italiana

trecentesca: ciò riguarda sia lo stile musicale, particolarmente sobrio,

che le scelte testuali, nei canoni di un lessico amoroso quanto mai

convenzionale. Del brano, una ballata purtroppo mutila, possediamo solo

la ripresa e parte del primo piede, mentre mancano del tutto il secondo

piede e la volta; la scelta interpretativa ha voluto dare risalto alla

linea melodica del canto, nel suo semplice declamato, senza tempo,

sostenuta dal liuto.

The Squarcialupi Codex contains Zachara's works in the most classical Ars nova

style: they were very probably written during his youth, in full

respect for the fourteenth century Italian tradition: as is reflected in

both the sober musical style and the choice of texts, with their very

conventional amorous vocabulary. Of this ballata, unfortunately

incomplete, only the refrain and a part of the first piede survive, while the second piede and the volta

are missing. This CD performance has chosen to emphasise the vocal

melody, with its simple unmeasured declamation, accompanied by the lute.

6. Ciaramella me' dolze (Lucca, Archivio di Stato, ms. 184, codice Mancini)

Flauto da tamburo: FT; ciaramella: MF; tromba a tiro: PC; rullante: SP.

Pipe and tabor: FT; shawm: MF; slide trumpet: PC; side drum: SP.

Il

riferimento al lo strumento musicale fatto da Zachara in questo brano è

stato raccolto: la ciaramella, in questa versione strumentale della

ballata, snoda una specie di contracantus all'improvviso (immaginandola nell'esecuzione di una cappella strumentale alta, cioè formata da strumenti dal suono potente), sostenuta dalla tromba a tirarsi al tenor e dal flauto da tamburo al cantus.

In

this work Zachara's mention of the shawm was taken into consideration:

the shawm, in this instrumental version of the ballata, performs a kind

of "contracantus all'improvviso" (imagining it as an "alta cappella" performance: that is, with loud instruments), while the tenor is accompanied by the slide trumpet and the "cantus" with the pipe and tabor.

(Marco Ferrari)

7. Ferito già d'un amoroso dardo (Firenze, Bibl. Mediceo-Laurenziana, Pal. 87, codice Squarcialupi)

Voci: AF, SP.

Voices: AF, SP.

Ferito già

appare, nel codice Squarcialupi, il primo della sezione dedicata a

Zachara (è quello al quale si accompagna il ritratto dell'Autore che

vediamo riprodotto in copertina), dunque fu evidentemente considerato,

da colui che progettò questa silloge, il brano più rappresentativo del

nostro compositore. Dobbiamo tuttavia pensare che il manoscritto

fiorentino è un manoscritto estremamente conservatore, concepito

appositamente per salvaguardare, in un periodo in cui la tradizione

vivente di questa musica era già sparita da tempo, i migliori esemplari

della stagione arsnovistica italiana. Ferito già, a ben guardare,

non è fra i brani più caratteristici dell'Autore; è, al contrario,

quello che più rispecchia i canoni del la nostra musica trecentesca: il superius melismatico, il tenor

con funzione di sostegno; prima e seconda voce maggiormente

differenziate tra loro, sia per virtuosismo che per tessitura, un testo

quanto mai convenzionale, col richiamo al topos del la freccia lanciata dallo sguardo della persona amata.

"Ferito già" is the first work of the section dedicated to Zachara in the Squarcialupi

Codex (it is that with the composer's portrait, reproduced on the cover

of this CD); thus, it was apparently considered by the compiler of the

collection to be his most representative work. We should however

remember that the Florentine manuscript is an extremely conservative

one, compiled in a period when the living tradition of the music had

already disappeared, in order to preserve the best examples of the

Italian Ars nova tradition. "Ferito già", on close examination,

is not one of the most characteristic works of Zachara; on the contrary,

it is the one which most adheres to fourteenth century musical models,

with its melismatic superius, the supporting role of the tenor,

the great differences between the first and the second voice, both in

virtuosity and in tessitura, and the conventionality of the text,

referring to the "topos" of the arrow shot by the beloved's eyes.

8. Deus deorum Pluto (Lucca, Archivio di Stato, ms. 184, codice Mancini)

Voci: SP, DB; viella: FT.

Voices: SP, DB: fiddle: FT.

In

questo brano abbiamo una primitiva attestazione dell'uso di tessiture

basse per la rappresentazione o il riferimento a divinità infernali. Qui

Plutone, dio degli inferi, è tuttavia chiamato in causa per la sua

seconda peculiarità, ovvero quella di essere anche il dio del denaro,

materia particolarmente cara all'Autore. In un testo sicuramente non tra

i più facili, scorgiamo i tratti evidenti di un autobiografismo

beffardo e quanto mai disinvolto, anche nel mettere in evidenza

meschinità e difetti, quali, per esempio, come in questo caso, l'avidità

("Or te rengrazio, poiché son reintegrato ...") e la subordinazione dell'arte al denaro ("per nessun commessa c'è pigrizia"),

se si viene largamente retribuiti. Il timbro scuro, le dissonanze

vocali, cui fa eco lo strumento ad arco suonato polifonicamente, piegato

a sonorità desuete, talvolta taglienti, evidenziano ancor meglio quanto

di insolito ed inquietante caratterizza questa ballata.

This

work is an early example of the use of low tessituras to represent or

refer to the gods of Hell. But here Pluto is invoked for his secondary

characteristic: he is also the god of money, a subject especially dear

to Zachara's heart. In a text by no means easy of comprehension, we can

discern traits of a personal nature, emphasising his meanness and

defects, such as avidity ("Or te rengrazio, poiché son reintegrato") and his readiness to subjugate art to money if the remuneration is high enough ("per nessun commessa c'è pigrizia").

The dark timbres, the vocal dissonances, echoed polyphonically by the

fiddle, with unusual, sometimes harsh resonances, emphasise the striking

and disquieting features of this ballata.

9. Movit'a pietade (Firenze, Bibl. Mediceo-Laurenziana, Pal. 87, codice Squarcialupi)

Flauto doppio: MF.

Double flute: MF.

Il

flauto doppio pone un affascinante problema a chi si interessi di

organologia e di prassi strumentale storica: si sa dell'esistenza certa

dello strumento, rappresentato più volte nella produzione figurativa

italiana del XIV secolo; l'innegabile difficoltà nel padroneggiare due

flauti separati e la scarsa corrispondenza con un qualsiasi repertorio

coevo, rendono complessa un' ipotesi sul suo impiego, e tuttavia la sua

stessa struttura di flauto polifonico e le peculiarità esecutive

suggeriscono svariate soluzioni. Questa ballata tardo-trecentesca è

stata prima minuziosamente analizzata, e perciò appresa a memoria, poi,

filtrata attraverso le possibilità tecniche del flauto doppio,

riproposta come repertorio suo tipico: privata del testo e dei suoi

accenti, sospesa all'instancabilità della respirazione circolare,

propria della tradizione italiana degli strumenti policalami, quali

zampogne e launeddas.

The double flute poses a fascinating

problem for scholars of instrumental praxis and organology. The

historical existence of this instrument is indisputable (it has often

been portrayed in Italian fourteenth century paintings), but, because of

the undeniable difficulty in mastering two separate flutes and the

scarce correspondence with coeval repertory, it is difficult to devise a

theory about its use. However, its structure (a polyphonic flute) and

performing peculiarities suggest several solutions. This late fourteenth

century ballata has been first meticulously analysed, then learnt by

heart and at last, through the technical possibilities of the double

flute, performed in a way typical of its repertory: without a text and

its accents, it is suspended by circular respiration, in the tradition

of Italian polypipes such as the bagpipe and the launeddas.

(Marco Ferrari)

10. E ardo in un fuogo (Strasburgo, Stadtbibl. 222)

Voci: AF, SP; vielle: BH, FT.

Voices: AF, SP; fiddles: BH, FT.

E ardo in un fuogo è una ballata sprovvista, come Movit'a pietade,

del secondo piede e della volta, e che, come quest'ultima, appartiene

probabilmente al primo Zachara. Compaiono tuttavia in questa

composizione tratti che si distaccano anche dallo stile trecentesco più

tradizionale, per essere ricondotti a stilemi, se vogliamo, ancora più

arcaici, individuabili in un piccolo numero di composizioni a cavallo

tra XIV e XV secolo, che Nino Pirrotta ha individuato col nome di siciliane.

Caratteristica della siciliana è la pari importanza delle voci, la

tessitura simile, il declamato semplice, contenuto nei melismi e,

soprattutto, la ripetizione di parti del testo (si noti, nel primo

piede, "E son per te ... e son per te" ) e una struttura musicale

senza una netta separazione tra strofa e ritornello: difatti qui il

materiale melodico e armonico esposto nella ripresa, viene riproposto

nel la mutazione con leggere varianti, senza che, tuttavia, accada

veramente qualcosa di nuovo. L' idea musicale viene continuamente

ribadita, secondo uno schema compositivo arcaicizzante di risparmio del

materiale tematico, tipico nella musica di tradizione orale.

"E ardo in un fuogo", like "Movit' a pietade", is a ballata lacking the second piede and the volta,

and again was probably written during Zachara's youth. However, this

composition has features which differ from those of the most traditional

fourteenth century style: they include even more archaic stylistic

characteristics, peculiar to a small group of compositions written

between the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, called "siciliane"

by Nino Pirrotta. The "siciliana" is characterised by equal importance

of the voices, a similar tessiture, simple declamation, restricted

melismas, and, above all, by the repetition of parts of the text (note,

in the first piede, "E son per te ... e son per te ...") and by a

musical structure without a clear separation between strophes and

refrains: in this work, in fact, the melody and the harmony of the

refrain reappear in slightly varied form in the mutzione, without

any really new elements. The musical idea is reused continually,

following an archaic compositional pattern typical of orally transmitted

music.

11. Je suis navrés / De quoy? / Gnaff'a le guagnele (Lucca. Archivio di Stato, MS 184. codice Mancini)

Voci: AF, SP, DB; vielle: FT, BH.

Voices: AF, SP, DB; fiddles: FT, BH.

Ancora

un brano in cui autobiografismo, polilinguismo, stile involuto

collaborano alla creazione di un effetto d'insieme particolarmente

elaborato. La prima voce, nel ritornello, si lamenta per le ferite

d'amore procurate dalle belle dame di AITNEROLF (Florentia), le altre la

esortano o intervengono con le loro domande. Nelle due strofe della

ballata si crea, invece, un effetto abbastanza ironico, dal momento che

la prima e la terza voce decantano il valore delle arti liberali, mentre

la parte centrale, che rappresenta, per così dire, una sorta di sguardo

cinico e disincantato sul mondo (e che, tutto sommato, corrisponde

abbastanza al carattere dell'Autore, particolarmente legato al denaro ed

ai piaceri terreni), non fa che contraddire le altre due, giungendo

persino ad affermare che coloro che nobilitano le arti sono più

soggiogati di un toro e non diverrano mai ricchi.

Again

a work in which autobiographical elements, polyglot texts and involuted

style create a particularly elaborate effect. The first voice, in the

refrain, complains of the wounds of love caused by the beautiful ladies

of AITNEROLF (Florentia - Florence), while the other voices exhort or

intervene with their questions. An ironic effect is created in the two

strophes of the ballata, because the first and the third voices extol

the virtues of the liberal arts, while the second, representing as it

were a kind of cynical and worldly view (rather in accordance with

Zachara's personality, in that he loved money and mundane pleasures),

contradicts continuously the other two, and goes so far as to claim that

he who ennobles the arts is more submissive than a yoked bull, and will

never become a rich man.

12. Un flor gentile anonimo - Zachara (Faenza, Bibl. Comunale, ms.117)

Liuto: FT; viella: BH.

Fiddle: BH; lute: FT.

Un fior gentile

è un brano proveniente dal codice Faenza 117, una raccolta composta

interamente di musica strumentale, per la maggior parte variazioni di

brani vocali trecenteschi. La versione cantata di questa ballata ci è

pervenuta con alcune lacune alla terza parte, dunque si è preferita la

versione diminuita di Faenza. Si tratta, sicuramente, di uno dei brani

meglio costruiti del nostro Autore: si potranno notare i lunghi fraseggi

della voce superiore, il dialogo delle parti nei brevi incisi, così

come, tuttavia, nella frase iniziale, in cui le voci entrano secondo un

procedimento imitativo (che, nella versione a tre voci, coinvolge anche

la parte più grave) in una vera scrittura fugata; infine la mobilità

ritmica, la frequente alternanza tra tempo binario e ternario, la

successione tra ampi episodi e brevi incisi sincopati. Si è a lungo

pensato che la musica del manoscritto fosse destinata all'esecuzione

organistica, mentre alcuni musicologi ritengono, oggi, che alcuni brani,

per le loro caratteristiche scritturali, siano più adatti agli

strumenti a corde. Anche per questo motivo abbiamo pensato ad

un'esecuzione per viella e liuto: il primo strumento mette meglio in

evidenza l'estrema cantabilità della voce superiore, mentre il liuto dà

al brano un forte impulso ritmico.

"Un fior gentile"

comes from the Codex Faenza 117, a collection including instrumental

music only, mostly variants of fourteenth century vocals works. The

vocal version of this ballata has survived with some lacunae in the

third part, thus we have preferred the Faenza version. It is definitely

one of Zachara's best structured works: note, in fact, the upper voice's

long phrases, the dialogue between the parts in the brief interchanges,

as also in the opening phrase, in which the voices enter in imitation

(including, in the three voice version, the lowest part), in true fugal

style; lastly, the rhythmic mobility, the frequent alternation between

binary and ternary rhythms, and the alternation of long phrases and

short syncopated motivic cells. It has been for a long time supposed

that this music was intended for organ, while some musicologists now

think that some pieces, because of their composing features, are more

suitable for string instruments. For this reason we have performed this

work on fiddle and lute: the former emphasises the highly vocal nature

of the upper part, while the latter gives a strong rhythmic impulse.

13. Plorans ploravi perché la Fortuna (Lucca, Archivio di Stato, ms. 184, codice Mancini)

Voci: GM, AF.

Voices: GM AF.

Plorans ploravi è un madrigale di cui, sino a qualche anno fa, si conosceva solo la voce di tenor;

le recenti scoperte di alcuni fogli appartenenti al codice Mancini e

del manoscritto Boverio, hanno consentito di completare questo brano,

che è sicuramente un'opera della tarda maturità dell'Autore, in uno

stile oggi definito ars subtilior. Elementi caratteristici di

questa maniera di comporre sono la ricca ornamentazione delle voci e, in

questo caso, la loro compenetrazione nei vari giochi imitativi, nelle

sincopi e nei ritardi; inoltre l'estrema complicazione del ritmo, che

passa di frequente da binario a ternario, talvolta con ardite

sovrapposizioni. Abbandonato lo stile arsnovistico più tradizionale e

suggestioni popolareggianti, questo brano, che accompagna, tra l'altro,

un testo piuttosto oscuro, ci porta in un'atmosfera quantomai rarefatta,

in un territorio in cui l'aspetto compositivo diviene soprattutto un

... gioco per iniziati.

Until some years ago we knew only the tenor part of the madrigal "Plorans ploravi":

the recent discovery of some sheets belonging to the Mancini Codex and

to the Boverio Fragment have 'Bowed us to complete this work, almost

certainly written by Zachara in his late maturity, using the style

called today "ars subtilior". Characteristic features of this

style of composition are the rich embellishment of the voices (and, in

this case, their interpenetration in imitative interplay, in syncopation

and retardation), and the complex structure of the rhythm, alternately

binary and ternary and sometimes both together. Remote from the

traditional Ars nova style and from popular influences, this

work, on a rather obscure text, has an extremely subtle atmosphere: a

world where compositional practices become "games for the initiated".

14. Ciaramella, m'è dolze (Lucca, Archivio di Stato, ms. 184, codice Mancini)

Voci: GM, AF, SP; bombarda: MF; tromba a tiro: PC; viella: BH; tammorra: FT.

Voices: AF, GM, SP; shawm: MF; slide trumpet: PC; fiddle: BH; tammorra: FT.

Ad

un linguaggio irriverente e licenzioso si abbina, in questa ballata,

uno stile compositivo colorito e piuttosto desueto. Le due voci

superiori, all'inizio dei due piedi, si richiamano tra loro, mentre

spesso la voce inferiore resta ferma su una nota di bordone, conferendo,

di tanto in tanto, al brano un senso della modalità più primitivo e

richiamando sonorità assimilabili a strumenti a fiato quali la zampogna

e, appunto, il ciaramello. La vivace interazione tra le voci, così come

quest'uso abbastanza anomalo per l'epoca, del pedale, sono tratti

distintivi del nostro Autore, che ritroviamo in molti altri brani.

In

this ballata a colourful and unusual style of composition are combined

with an irreverent and licentious text. At the beginning of the two piede

the two upper voices hold a dialogue, while the lower voice often rests

on a burden, sometimes giving the work a feeling of ancient modality

and recalling the resonances of wind instruments such as the bagpipe,

or, appropriately, the shawm (ciaramella). The lively interaction

between voices and the use of the pedal, somewhat anomalous for its

time, are distinctive characteristics of Zachara's style, to be found in

many of his other works.