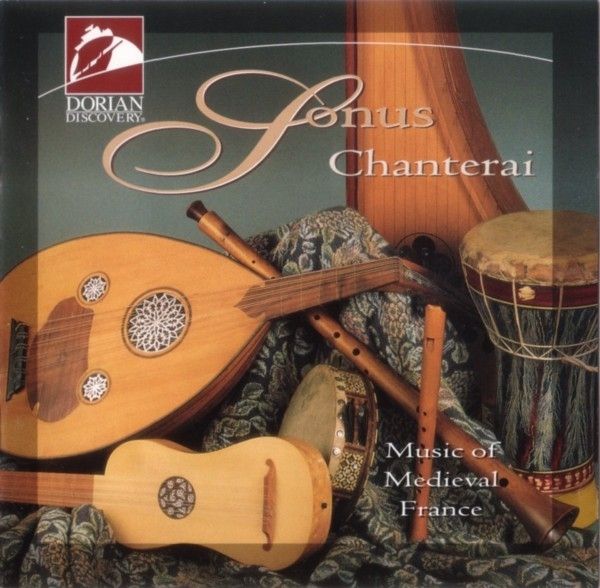

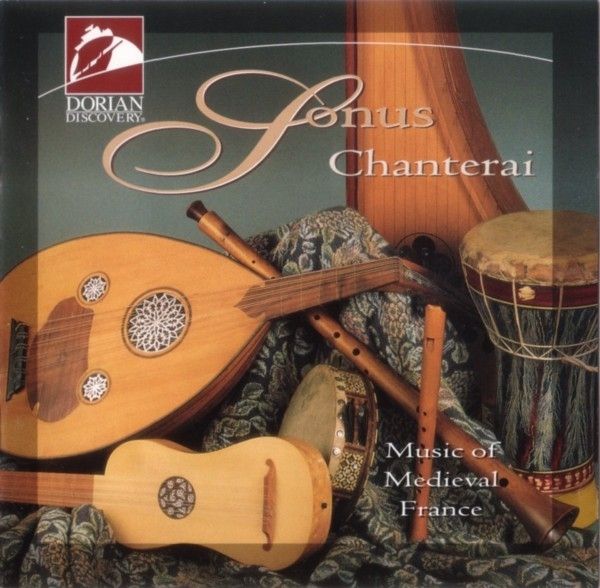

Chanterai / Sonus

Music of Medieval France

medieval.org

Dorian Discovery DIS-80109

1993

1. Dance — Penser ne doit vilenie [5:44] anon., 13th c.

oud JH, saz HK, dulcimer, recorder

2. Gaite de la tor [2:10] anon., 13th c.

gemshorn

3. Chanterai pour mon coraige [10:42] Guiot de DIJON, 12th c.

voice, oud JC, saz WM, percussion

4. Quan je voy le duc [3:05] Italian, 14th c.

oud JH, vihuela WM, recorder

5. Non es meravelha s'eu chan [7:54] Bernart de VENTADOUR, 12th century

voice, harp, dulcimer

6. Souvent souspire [4:22] anon., 13th c.

oud JH, saz WM, shawm, recorder, percussion HK

Guillaume de MACHAUT (1300-1377)

7. Quant je suis [3:57]

voice, chitarra WM, harp, psaltery

8. Je puis trop bien [2:26]

chitarra JH, vihuela WM, harp

9. De bonté, de valour [4:41]

voice, oud JC, saz WM, percussion

10. Ma fin est ma commencement [2:53]

chitarra JH, vihuela WM, harp

11. Gaite de la tor [2:15] anon., 13th c.

harp

12. Reis glorios [8:19] Guiraut de BORNELH, 12th century

voice, harp

13. Estampie real [5:09] anon., 13th c.

saz JH, recorder, percussion HK

Sonus

James Carrier: shawm, recorders, oud (3, 9), harp, gemshorn

Hazel Ketchum: voice, saz (1), percussion (6, 13)

John Holenko: oud (1, 4, 6), chitarra (8,10), psaltery, saz (13), percussion

Will Mason: saz (3, 6, 9), chitarra (7), vihuela (4, 8, 10), dulcimer, percussion

MUSIC OF THE TROUBADOURS AND TROUVÈRES

The beginnings of vernacular song in western music can be traced to

the 12th century troubadours

in the south of France. These aristocratic poet/musicians travelled

from court to court and benefited from the education and wealth of the

ruling classes. Their poems and songs were often spread by wandering jongleurs, the itinerant "professionals" of the time. Writing in the language of Provençal or langue d'oc, the troubadours

left us 2600 poems and 275 melodies. Musical influences were Gregorian

chant and the older Goliardic art. The subjects of the songs were

literary and political satire or some aspect of courtly love, idealized

and highly abstract. Chivalric romance presented a deification of woman,

mirrored in the feminization of the Divinity and worship of the Virgin.

The

cultural influences of the Crusades of 1147, marriages among the

aristocracy and travel helped to carry the troubadour art to the north.

There the trouvères developed their poetic and musical forms.

Much later, Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377) sought to recover this

world of chivalric art in monophonic and polyphonic song. He combined

the old trouvère forms with the polyphonic techniques developed

during the Gothic period. This complex musical genre using the resources

of the new polyphony resulted in the last great stylistic expression of

the Gothic and the last representation of the art of courtly love.

All

of the songs presented here express the medieval concepts of love and

chivalry. There is a variety of treatment, however, from the quiet

intensity of Non es meravelha s'eu chan to the emotional urgency of Chanterai por mon coraige. Non es meravelha is a troubadour canso

of Bemart de Ventadour. All eight lines of each stanza have the same

number of syllables and the same basic rhythm. But the final note of

each line of music changes: F, G, A, D, F, E, D. This, plus the

characteristic intervals of the melody, give the song a fascinating

tonal color. Chanterai por mon coraige is a chanson de croisade

in which a lady reflects on the absence of her lover who is on crusade

in Palestine. The accompaniment here is highly improvisatory in an

attempt to follow the rise and fall of this emotionally gripping text.

The age of chivalry could not be better represented than by Machaut's monophonic songs De bontè, de valour and Quant je suis, whose texts convey the epitome of idealized romance. Machaut's polyphonic art is explored in instrumental performances of Je puis trop bien and Ma fin est ma commencement. The latter is a remarkable rondeau

form in which the top part has the same melody as the tenor, but

backwards, while the contratenor has the same music from the beginning

to the middle and from the end backwards to the middle. The song speaks:

"my end is my beginning".

The opening dance is based on the trouvère chanson, Penser ne doit vilenie.

All of the melodic units to each line of the poem and to each of its

several refrains are variants of the same musical material. The

possibilities for heterophonic combination and elaboration makes this

excellent material for dance treatment. Estampie real is our own reworking of a dance found in a 13th century manuscript, the “Cbansonnier du Roi” The estampie, Souvent souspire was popular enough to have survived in four manuscript sources.

Quan ye voy le duc is actually an Italian caccia-madrigal, having two canonic parts over a supporting tenor. This one, however, is based on a French chanson, a rare instance in Italian trecento literature.

ABOUT THE PERFORMANCES

Our

choice of musical instruments is based on a study of instrument

representations in medieval iconography and on descriptions of

instruments and performances in literature of the period. Performers in

the middle ages had a degree of freedom foreign to later music-making.

Ideal performances or definitive versions did not exist. Indeed, variety

was sought for its own sake. In matters of tempo, instrumentation and

overall interpretation the performers could tailor a performance to

their own resources and abilities. Extemporizations of songs and dances

based on a general melodic repertoire were common practice. Instrumental

accompaniments and percussion parts were improvised and the ability to

invent instrumental preludes, interludes and postludes was highly

respected.

Many of the instruments of medieval Europe had their

origins in the Middle East: the psaltery, a plucked instrument having

strings of wire or gut stretched over a soundbox, had its predecessor in

the Arabic qa’nun; the hammer dulcimer derived from the Persian santur, the lute (al’oud) was brought to Europe by the Moors, as was the long-necked lute (saz) called the chitarra Morescha or Moorish guitar. The latter can be distinguished from the small, probably native, chitarra latina.

Double-reed shawms, predecessors of the oboe and bassoon, came from the

east. Recorders or end-blown flutes can be found in cultures around the

world, as can small harps. The musicians of the period used a wide

variety of drums, tambourines, cymbals, bells and clappers.

—James Carrier

SONUS

SONUS

The

Sonus ensemble was formed in 1988 to perform the medieval secular

repertoire. In search of a "sound picture" they explore a broad spectrum

of improvisational and timbral aspects in their presentation of this

literature. They were featured at the Piccolo Spoleto series in 1991,

'92 and '93.

James Carrier received B.M. and M.M. degrees

from Boston University where he studied bassoon and music history. In

1973 he joined the Cincinnati Early Music Consort and toured with that

ensemble through 1981. Since 1988 he has been a regular performer on the

Piccolo Spoleto Early Music series, performing with Sonus, Charleston

Pro Musica, Ensemble Courant, and others. In 1991 he played for the

Spoleto production of L'Incoronazione di Poppea.

Hazel Ketchum

began her musical career as a drummer, singer and songwriter at age 14.

She received her M.M. degree from the University of Southern

California, and studied guitar with James Smith and William Kanengiser

as well as early instruments and voice with Donna Curry and James Tyler.

Specializing in the art of self-accompanied song, she plays lute and

classical and historic guitars. She has been featured on radio programs

in New York, Los Angeles and on NPR's Performance Today. She has

performed across the United States appearing with Los Angeles Musica

Viva, Charleston Pro Musica, Early Fusion Consort, Sonus and others.

John Holenko

graduated from the New England Conservatory of Music and the University

of Southern California, studying guitar and historical performance at

both institutions. As a guitarist he regularly performs contemporary

music and has premiered numerous compositions. He has performed at the

Piccolo Spoleto series with Sonus, Charleston Pro Musica and in concert

with Hazel Ketchum. In addition to teaching, he hosts the program Fretwork on South Carolina Public Radio and coordinates his own Fretwork series for Piccolo Spoleto.

Will Mason is a graduate of the University of Southern California where he studied early music performance with James Tyler. While specializing primarily on 16th century vihuela music and early 17th century music for chitarrone, he plays a wide range of plucked instruments from the middle ages through the baroque. Performing from Vancouver to the Bahamas to Prague, Mr. Mason has been a member of the London-based ensembles Circa 1500 and Sol Terrenus and now appears regularly with Sonus.

INSTRUMENTS HEARD ON THIS RECORDING

Shawm: Günter Körber

Recorders: Levin-Silverstein

Harp: S. Brook Moore

Psaltery, hammer dulcimer, gemshorn: Ben Bechtel

Chitarra: Larry Brown

Vihuela: Steven Barber

Oud: Syria (anon.)

Chitarra Morescha (saz): Turkey (Anon.)

Percussion: assorted Middle Eastern (Anon.)

SOURCES AND EDITIONS CONSULTED:

J. Beck, ed., Le Manuscrit du Roi (Philadelphia, 1938).

F. Ludwig, Guillaume de Machaut: Musikalishes Werke (Leipzig, 1926-29; Wiesbaden, 1954).

W. T. Marrocco, Fourteenth Century Italian Cacce (Cambridge, Mass., 1942).

L. Schrade, Works of Guillaume de Machaut, Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century (Monaco, 1956).

Paris, Bibliotheque l'Arsenal, 5198.

Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, Ms Fr. 844.

Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Fr. 846.

Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Fr. 20050.

Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Fr. 22543.

SONUS

CHANTERAI: MUSIC OF MEDIEVAL FRANCE

CATALOG NO. DIS-80123

Recorded at St. John's Episcopal Church, Columbia, Maryland, September 1993

Producer: Paul Bensel

Engineer: Paul Bensel

Editor: Paul Bensel

Mastering Engineer: Brian C. Peters

Booklet Preparation & Editing: Brian M. Levine

Graphic Design: design M design W

© 1993 Sonus ℗ 1994 DORIAN DISCOVERY