medieval.org

LP 1974: EMI Reflexe 1C 063-30123

CD 2000: EMI Classics 8 26492 2

Seite 1

Aufgenommen: 1.-3.V.1973, München, Bürgerbräu

1. Planctus David [22:31]

Andrea von Ramm, mezzosoprano, organetto

Richard Levitt, alto, percussions

Sterling Jones, lyra, rebec

Thomas Binkley, lute

Seite 2

Aufgenommen: 14.-17.VI.1974, Berlin, Studio Zehlendorf

2. Planctus Jephta [15:24]

Andrea von Ramm, mezzosoprano

Sally Smith, Barbara Thornton, Pilar Figueras, Montserrat Savall (CD: Figueras) – singers

Sterling Jones, lyra

Thomas Binkley, flute

Richard Levitt, tabor

Hymnus

3. O quanta qualia [7:48]

Andrea von Ramm, mezzosoprano

Richard Levitt, alto

Sterling Jones, chitarra saracenica

Thomas Binkley, lute

CD:

Produzent: Gerd Berg

Tonmeister: Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

Titelbild: Héloise und Abélard, Miniatur aus

Le Roman de la Rose von Jean de Meung (15. Jhdt.-);

Château de Conde, Chantilly

Cover-Design: Patelli

Litho: Repro Schmitz KG, Cologne

Ⓟ 1974 EMI Electrola GmbH

Digital reamastering Ⓟ 2000 by EMI Electrola GmbH

© 2000 by EMI Electrola GmbH

THE MUSIC OF PETER ABELARD

Peter

Abelard (1079-1142) was born in Pallet near Nantes, the first son of a

noble family. Going against tradition as he did all of his life,

Abelard looked for a career of the mind rather than to continue his

family traditions. He studied dialectic and describes himself as a pupil

of Roscellinus, canon of Compiègne (died after 1120), master of

Nominalism. When but twenty he went to Paris where he visited the

lectures of William of Champeaux, the disciple of St. Anselm, who

related faith and reason in an attempt to establish proof of God'd

existence. There was real conflict! Boethius' Universals were at the

bottom of it: for Anselm, the rational and the real were one, white for

Roscellinus only the individual entities were real - the persons of the

Trinity were real, the idea of Trinity unreal. Abelard crystallized a

new aid moderate position after defeating his teacher William who had to

admit that his theory of essences was not tenable. Abelard viewed

Universals as real things but only in the object, and neither

before nor after it. (Unknown to Abelard, this same discussion had been

resolved in a similar manner by Arab philosophers in the previous

century). About 1115 he was given the chair at Notre Dame. He got into

difficulty when he applied his doctrine to the Trinity, but this

difficulty was less crucial in his life than another, more violent one

Abelard,

young, personable, brilliant and famous teacher in Paris, became

attracted to the niece of the canon Fulbert, and this young woman was

herself of good house, attractive and unusually quick of mind. Abelard

became resident in the house of Fulbert and teacher to his niece

Héloise. The love between the pair is a story often told - how Héloise

became pregnant, how Fulbert discovered the relationship, how Héloise

went to Brittany where she gave birth to a son, how Abelard married her

under a promise of secrecy (to protect his career), and how Fulbert

broke the secrecy. Héloise's womanly devotion led her to deny that she

was married to Abelard and with Abelard's help went to her childhood

convent of Argenteuil. Fulbert, humiliated by Héloise's bold and drastic

actions, and firmly believing that Abelard was throwing her off,

organized his revenge. By dark of night Fulbert's two envoys broke into

Abelard's room and castrated him. Abelard then experienced years of

abject misery. He could no longer become a priest nor hold canonic

office. He went to the Abbey of St Denis but found no peace there. He

returned to teaching, but was charged with the heresy of Sabellius

because of his rational approach to the Doctrine of the Trinity.

His

teaching temporarily at an end, he was shut up in a monastery. He was

unpersonable, disliked, and soon forced to leave because of his talent

for find, objectionable and sensitive questions for debate. He tried to

become a hermit, but his solace was broken by the arrival of large

numbers of students who replaced his hut with a building which since

then has born the name Paraclete. Abelard left the Paraclete to assume

the directorship of an abbey in the North, of St Gildas de Rhys. There

he struggled for ten years with an unruly house which defied reform and

very nearly saw Abelard killed. Héloise, who had taken orders at

Agenteuil was in search of a new place when she and her nuns were

evicted. Abelard was able to have her installed in the Paraclete which

had been empty since he moved away. Faced with the threat of violence at

St Gildas, Abelard left. Soon after he produced his Historia Calamitatum, a sort of autobiography. A copy of the Historia

reached Paraclete, and Héloise's reaction was to begin a correspondence

with her husband and former lover, from whom she had no communication

for about a dozen years. Héloise probably did not know all the

misfortunes of Abelard since the separation, She points out that he is

wasting his efforts to reform people who pay no attention to him while

the nuns at the Paraclete would respond eagerly to his advice and

encouragement. She demands a personal explanation of Abelard's silence

and lack of acknowledgement of Héloise sacrifice of entering monastic

life out of love not of God but of Abelard. Abelard's response was to

write to Héloise as an abbot to an abbess, and to refuse to be engaged

on a persona level. He refers to the power of prayer and the integrity

of faith. Héloise replied that she had taken vows because of Abelard,

that the sexual frustration she experienced was severe and that she

found it hateful to live such a hypocritical life. This letter is full

of passion and painful in its description of a soul in desperate agony.

His

teaching temporarily at an end, he was shut up in a monastery. He was

unpersonable, disliked, and soon forced to leave because of his talent

for find, objectionable and sensitive questions for debate. He tried to

become a hermit, but his solace was broken by the arrival of large

numbers of students who replaced his hut with a building which since

then has born the name Paraclete. Abelard left the Paraclete to assume

the directorship of an abbey in the North, of St Gildas de Rhys. There

he struggled for ten years with an unruly house which defied reform and

very nearly saw Abelard killed. Héloise, who had taken orders at

Agenteuil was in search of a new place when she and her nuns were

evicted. Abelard was able to have her installed in the Paraclete which

had been empty since he moved away. Faced with the threat of violence at

St Gildas, Abelard left. Soon after he produced his Historia Calamitatum, a sort of autobiography. A copy of the Historia

reached Paraclete, and Héloise's reaction was to begin a correspondence

with her husband and former lover, from whom she had no communication

for about a dozen years. Héloise probably did not know all the

misfortunes of Abelard since the separation, She points out that he is

wasting his efforts to reform people who pay no attention to him while

the nuns at the Paraclete would respond eagerly to his advice and

encouragement. She demands a personal explanation of Abelard's silence

and lack of acknowledgement of Héloise sacrifice of entering monastic

life out of love not of God but of Abelard. Abelard's response was to

write to Héloise as an abbot to an abbess, and to refuse to be engaged

on a persona level. He refers to the power of prayer and the integrity

of faith. Héloise replied that she had taken vows because of Abelard,

that the sexual frustration she experienced was severe and that she

found it hateful to live such a hypocritical life. This letter is full

of passion and painful in its description of a soul in desperate agony.

Abelard's

response is a light reprimand. He will not bring up the past with

nostalgic remorse. They had sinned. They had made love in the nunnery of

Argenteuil and even during the Passion Season they had made love in the

house of Fulbert, and in many other ways they had taken God lightly.

She should look to Christ who really loved her and who had suffered more

for her than had Abelard.

Never again did the two exchange

personal letters. They did continue to communicate with each other but

always in matters of institutional significance. Héloise ask for advice

in regulating matter at the Paraclete, how the nuns should dress and how

much work they should do. She asks for information on he history of

nuns and nunneries, and advice on food. Abelard prepared two long Letters of Direction, still formal documents.

In

another letter of Abelard we find a response to one now lost of Héloise

in which Héloise had requested that Abelard write new hymns for the

Paraclete. Abelard notes in his letters that Héloise's reasons for the

request are strong: " ... I have written what are called hymns in Greek

and tehillim in Hebrew. At first I thought it superfluous for me to

write new hymns when you had plenty of old ones ... (but you wrote) that

the Latin Church in general and the French in particular follows

customary usage rather than authority as regards both hymns and psalms

... the translation of the psalter is of doubtful origin ... the hymns

are in considerable confusion ... the words so irregular that is

impossible to fit them to the melodies ... " (Cousin vol. 1 p. 296-8).

Evidently Abelard sent a total of 133 Hymns to the Paraclete in three

books.

In another letter Abelard seems to refer to the six Planctus

(Laments) he composed when he wrote: "I recently completed at your

request a little book of hymns or sequences (!) ... and then as you

asked me several short sermons." (Cousin vol. 1 p. 350). Abelard

explains that he placed emphasis on the literary clarity in the sermons

(and also the sequences?) in order to be able to reach the women (in the

Paraclete) of little understanding.

If we keep in mind that hymn meant for Héloise simply the praise of God in song,

and that Abelard equated his real hymns with the Greek word and the

Hebrew word, but when referring to this "little book" he equates them

with sequences, which in essence the planctus are, then it seems

convincing that his "little book of hymns or sequences" is the

collection of six planctus and not part of the 133 hymns.

There

is no evidence that Abelard ever again visited the Paraclete nor came in

personal contact with Héloise. Apparently was teaching in Paris when

his final great conflict occurred, his conflict with Bernard of

Clairvaux, St Bernard. Bernard, a Cistercien, offered an alternative to

the dominant Benedictine rule of Cluny, at that time led by another

great man, Peter the Venerable. The difference between these two rules

is important: the Benedictine rule was older and attempted a life

according to the spirit of the law, white the Cistercien was a

new order attempting to revive the asceticism of the "Desert Fathers of

Anthony, friend of Athanasius, Archbishop of Alexandria, and the fratres peregrinos.

Bernard believed that faith, not learning led to Christ. Nothing should

be learned that was not learned in the pursuit of Salvation.

There

is no evidence that Abelard ever again visited the Paraclete nor came in

personal contact with Héloise. Apparently was teaching in Paris when

his final great conflict occurred, his conflict with Bernard of

Clairvaux, St Bernard. Bernard, a Cistercien, offered an alternative to

the dominant Benedictine rule of Cluny, at that time led by another

great man, Peter the Venerable. The difference between these two rules

is important: the Benedictine rule was older and attempted a life

according to the spirit of the law, white the Cistercien was a

new order attempting to revive the asceticism of the "Desert Fathers of

Anthony, friend of Athanasius, Archbishop of Alexandria, and the fratres peregrinos.

Bernard believed that faith, not learning led to Christ. Nothing should

be learned that was not learned in the pursuit of Salvation.

Clearly

the clash between Abelard and St. Bernard was of far greater meaning

than simply the clash between two strong and proud men: it was the

search for the resolution of a cardinal problem of the 12th century.

Abelard feels that with his knowledge he is defending the Christian

faith white Bernard feels that faith transcends knowledge. The problem

was not resolved. Alter considerable intrigue, Bernard was able to see

Abelard declared a heretic and his followers excommunicated. Peter the

Venerable intervened on the side of Abelard and the sentence was

rescinded. A year and a half later Abelard died in a Cluniac monastery

at St. Marcel near Châlon-sur-Saône.

Astralabe, the son of

Abelard and Héloise never pictured prominently in the lives of the two.

One simple event: Astralabe (an anagram of the French version of

Abelard, Esbaillard = Asbelart?) was aided by Peter the Venerable to

obtain a church benefice after Abelard's death.

One is tempted to

treat the collection of Latin Planctus as part of the catharsis

attempted by Abelard during Me 1130s about the time he wrote the Historia Calamitatum.

All of the planctus are old-Testament situations of human calamity.

Jacob's ravished daughter. Jacob's lament as his youngest son Benjamin

leaves for Egypt, lsraeli vergines lament the daughter of Jephta, the

people of Israel lament the death of Samson and David laments the death

of Saul, Jonathan and Abner. There is no previous tradition to account

for Abelard's selecting to write such accounts of biblical stories. As

mentioned above, they were probably written for the nuns of the

Paraclete to make the suffering in stories more real by retelling them

in the first person.

All six Planctus are contained in the

manuscript Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apost. Vaticana Cod. Reg. lat.

288. Many attempts have been made to transcribe the staffless neums in

this manuscript but none have been really successful. More recently with

the discovery of these works in other manuscripts it is possible to

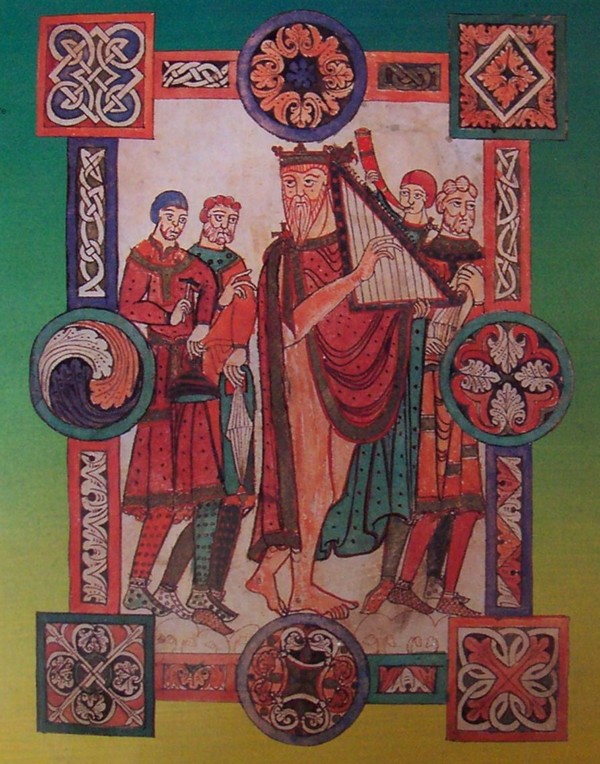

come somewhat closer to the original. The David Planctus survives in the

manuscript Oxford University Library Ms, Bodl. 79 fol. 53'-56, an

English 13th century manuscript written in square notation on a

four-line staff. Another version of the David Planctus is contained in

the manuscript Paris Bibl. Nat. f. nouv. a. Latin 3126, fol. 88'-90'.

This is a late 12th century manuscript also written in square notation

on a four-line staff.

There are no knowm concordant sources fort

other Abelard Planctus, although material help in the transcription of

Jephta comes in its proximity to a French Secular piece, the lai des pucelles.

The manuscript, Paris Bibl. Nat. f. fr. 12615, fol 711, 13 century,

presents this piece in square notation on a five-line staff. Although by

no means identical to the Abelard Planctus, it is very similar to it.

We

cannot pretend that these melodies are absolutely identical to

Abelard's, any more than we can be certain the Vatican manuscript

preserves the melodies in original form, however it is important to

stress that this element of historical accuracy is less necessary than

in much other music. The melody is not composed as an expressive line

complementing the text but rather, as is very common in 12th century

composition, fragments of melodic material are architecturally combined

to enhance the structure of the poetry. Thus it is possible to find wide

differences in the preserved melodies of the David Planctus, for

example, without any being wrong, nor less well fulfilling the function

of that melody.

If the reader will agree with me that these

Planctus were originally written by Abelard for the nuns of the

Paraclete, then it is not unreasonable to perform one as it might have

been done there, sung by female voices. The use of instruments is

perfectly in keeping with Héloise's rule there as well as in harmony

with French practice of Adam of St. Victor and others. In the case of

the David planctus we have made the Performance somewhat later in style

in conformity with the later sources, a performance in a more

international vein.

The hymn O quanta qualia was still

more popular than any of the Planctus. It is one of the four hymns that

became part of the repertory of the cloisters other than the Paraclete.

We find it in a manuscript at St. Gall, Stiftsbibl. 528, containing the

repertory of the Großmünster in Zürich (14th century), and it was a

permanent part of the repertory al the Cistercian abbey ot Rheinau. How

ironic that St. Bernard's Cistercians should be the ones to transmit a

hymn of Abelard, for apart from more major differences between the two,

Abelard once admonished Bernard for composing new hymns which Abelard

felt were superfluous! Héloise had written to Abelard that hymns were

the praise of God in song, that she needed them for her nuns, and

Abelard wrote them with the idea that they be easy to learn and to

remember. It seems reasonable to suppose that these hymns were not only

liturgical but were devotional. Thus the performance here is not that

expected in the celebration of the mass but that of the oratory.

The

music of Peter Abelard will never attain the stature of his

philosophical importance, yet it is one side of a remarkable personality

and helps to complete a picture of this man of the 12th century, a man

of the mind, of the flesh and of the spirit, a man of pride and passion

and of suffering

Thomas Binkley

Bibliography:

· V. Cousin, Petri Abaelardi opera, Paris 1848

· Lorenz Weinrich, Peter Abélard as Musician, MQ vol. LV No. 3-4

· Giuseppe Vecchi, Pietro Abélardo I, Modena 1951

· E. M. Bannister, Monumenti Vaticani..., vol. XII, Leipzig 1913

· Bruno Stäblein, MMMA 1. Kassel 1956

· Additional bibliography of Weinrich