English liner notes

TROUBADOUR EN JONGLEUR

Voor

een verklaring over de vrij plotselinge opkomst van de

troubadourslyriek aan het begin van de 12de eeuw zijn we aangewezen op

veel giswerk en theorieën, over de opbloei van de economie in het zuiden

van het huidige Frankrijk, Noord-Italië en Noord-Spanje, contact met de

Arabische cultuur... Beter zijn we geïnformeerd over de ondergang van

deze kunst. Tijdens de eerste en tweede kruistocht tegen de Albigenzen

(1209-1244) werden, in een verbond tussen de Paus en de koning van

Frankrijk, de Provence en omliggende streken veroverd, ketters verbrand,

beschermheren en beoefenaars van de kunst vermoord en het gebied

ingelijfd bij dat van de koning.

De taal van de troubadours was het Occitaans,

een romaanse taal met elementen uit het Vulgair Latijn, Spaans, Frans

en Arabisch. Het bestaan van de Occitaanse cultuur is lange tijd in

Frankrijk ontkend. In 1539 werd het gebruik van het Occitaans door

François I verboden. Tegenwoordig wordt in enkele streken in

Zuid—Frankrijk het Occitaans weer op scholen onderwezen. Diverse

dichters, zangers en popgroepen gebruiken de taal, niet alleen in de

traditionele volksmuziek, maar ook in hun protest tegen de Franse

centralistische politiek en de milieuvervuiling, evenals bij het uiten

van de wens tot zelfbestuur.

Hoofdthema van de troubadourslyriek was de fin amors, veelal vertaald als hoofse liefde.

Centraal stond het verlangen naar de niet aanwezige, bijna onbereikbare

Dit was lettertype/tekenbreedte 1,10 — Aan. — want veelal met een ander

gehuwde — geliefde. De fin amors gold hierbij als tegenpool van

de op politiek—economische gronden gevestigde huwelijksverbintenis,

gebruikelijk in kringen van hogere stand in die tijd. Men dient het

begrip fin amors/hoofse liefde niet te verwarren met platonische liefde; de aanwezige literatuur geeft daar zeker geen aanleiding toe.

Uit de vida (levensbeschrijving) van Guilhem de Peitieus,

9de graaf van Aquitaine (1071-1127), de eerst ons bekende troubadour

waarvan gedichten bewaard zijn gebleven: "De graaf van Poitiers was

zowel een van de belangrijkste edelen ter wereld als een van de grootste

bedriegers van vrouwen, een ridder bedreven in de wapen — en

versierkunst. Ook kon hij goed dichten en zingen".

Vida's

zijn de levensbeschrijvingen van de troubadours en de trobairitz

(vrouwelijke troubadours). Ze werden meestal jaren na de dood van de

troubadour in kwestie opgetekend. Het betreft hier teksten die de

jongleurs voordroegen ter introductie van de door hen ten gehore

gebrachte liederen.

Erg betrouwbaar zijn deze vida's niet, maar

het zijn wel de enige feitelijke gegevens die over de troubadours

bewaard gebleven zijn. De vida's van Beatritz de Dia, Giraut de Borneill en Bernart de Ventadorn luiden als volgt:

'La Comtessa (Beatritz) de Dia

was de echtgenote van Willem van Poitou en een schone, goede vrouw. Ze

werd verliefd op Raimbaut d'Orange en schreef over hem vele goede

liederen'

'La Comtessa (Beatritz) de Dia

was de echtgenote van Willem van Poitou en een schone, goede vrouw. Ze

werd verliefd op Raimbaut d'Orange en schreef over hem vele goede

liederen'

'Giraut de Borneill

kwam uit de Limousin, uit de streek rond Exideuil, van een machtig

kasteel van de burggraaf van Limoges (Aimar V, 1148-1199). Hij was een

man van lage afkomst, maar een ontwikkeld man door zijn kennis en zijn

aangeboren intelligentie. Hij was een beter troubadour dan enig ander die vóór hem bestaan had of die na hem zou komen; hij werd dan ook de meester-troubadour genoemd

en zo wordt hij nog steeds beschouwd door degenen die subtiele,

welgekozen woorden van liefde en geest verstaan. Hij werd zeer

gewaardeerd door edelen, door kenners en door vrouwen die bijzondere

aandacht schonken aan de volmaakte teksten van zijn liederen. Zijn leven

was zo ingericht dat hij de gehele winter op school les gaf in de

letteren en de gehele zomer langs de hoven trok met twee jongleurs

die zijn liederen zongen. Hij heeft nooit iemand tot vrouw willen nemen

en schonk alles wat hij verdiende aan zijn behoeftige ouders en aan de

kerk van zijn geboortedorp; die kerk heette en heet nog steeds de

Saint-Gervais'

'Bernart de Ventadorn

kwam van het kasteel Ventadorn in de Limousin. Hij was een man van

geringe afkomst, de zoon van een dienaar die als ovenist de oven stookte

waarin het brood voor het kasteel gebakken werd. Hij groeide uit tot

een mooi en behendig man. Hij kon zeer goed zingen en "vinden" en werd

een hoffelijk en geleerd man. En de graaf van Ventadorn werd zo door hem

en door zijn wijze van zingen en "vinden" gecharmeerd, dat hij hem veel

eer betoonde. Nu had de graaf van Ventadorn een jonge, edele en

vrolijke vrouw. Bernart viel met zijn liederen bij haar in de smaak en

zij raakte verliefd op hem en hij op haar; zo maakte hij zijn verzen en

liederen met haar, de liefde die hij voor haar koesterde en haar

verdiensten als onderwerp. Hun liefde duurde lang, eer de graaf of

iemand anders het bemerkte. En toen de graaf zich ervan bewust werd,

scheidde hij zijn vrouw van Bernart en liet haar opsluiten en bewaken.

De vrouwe moest Bernart gedaan geven en hem verzoeken te vertrekken en

zich uit de streek te verwijderen. Hij vertrok en ging naar de hertogin

van Normandië, die jong was en grote verdiensten had en bekwaam was in

vele zaken van eer en schone, loffelijke taal. De verzen en liederen van

Bernart vielen zeer bij haar in de smaak en ze ontving hem zeer

hartelijk en nam hem op. Hij verbleef lang aan haar hof, werd verliefd

op haar en zij op hem. Terwijl hij bij haar was, nam de koning van

Engeland, Hendrik, haar ten huwelijk, waardoor ze Normandië moest

verlaten om zich in Engeland te vestigen. Bernart bleef, triest en

aangedaan, aan deze kant van de zee en begaf zich naar de goede graaf

Raimond van Toulouse; hij bleef tot aan zijn dood onder diens hoede. En

om de smart die Bernart doorstaan had, trad hij toe tot de orde van

Dalon, bij welke hij zijn levensdagen beëindigde.

En wat ik, Uc

de Saint-Circ, over hem geschreven heb, werd mij overgebracht door de

burggraaf Eble van Ventadorn, die de zoon was van de burggravin die

Bernart bemind had'

De jongleurs

Voor de troubadours geldt het primaat van de taal, het Occitaans.

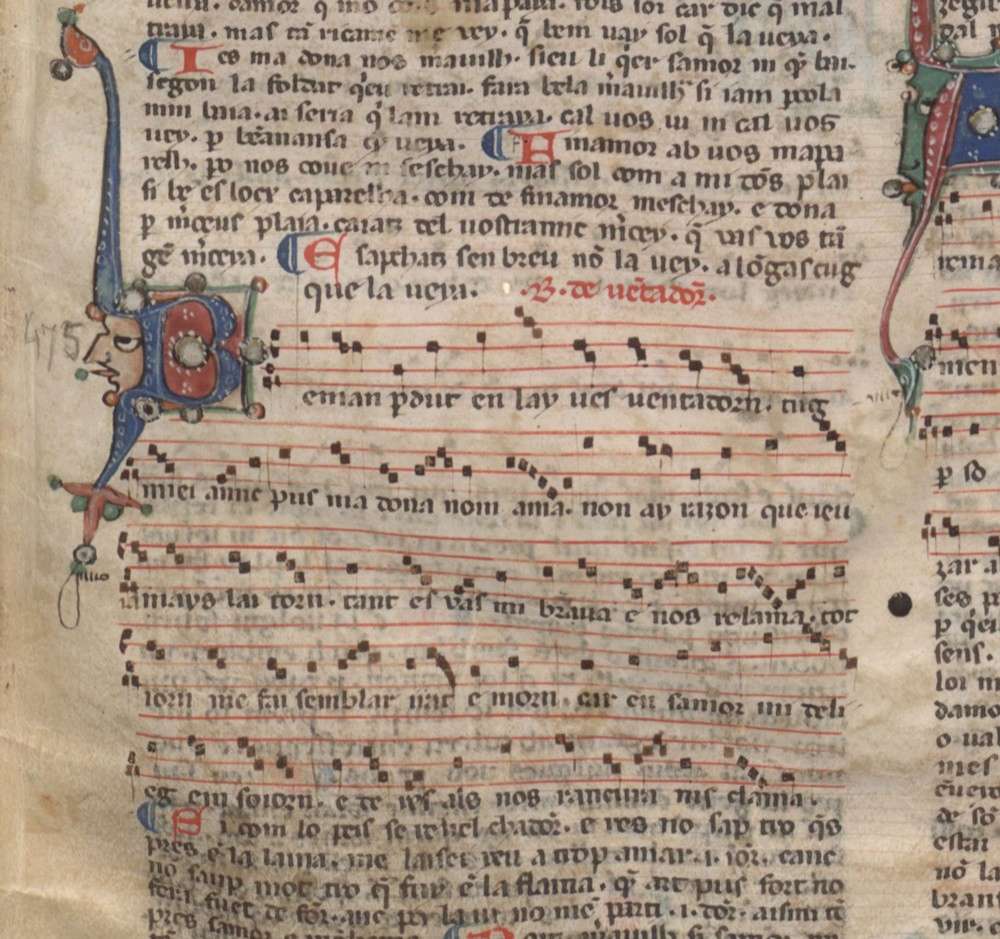

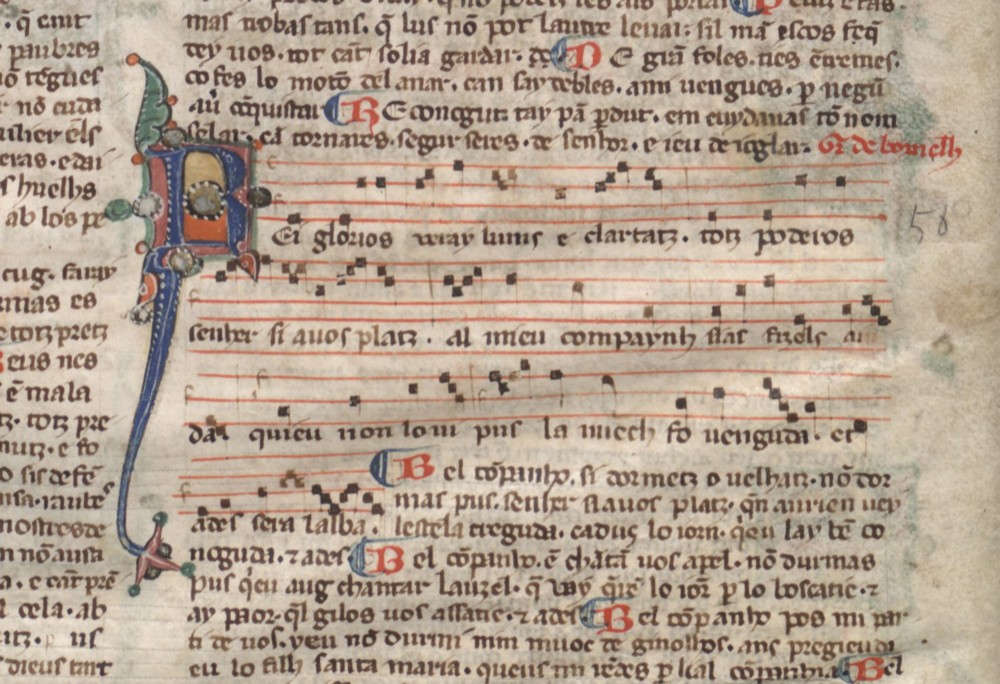

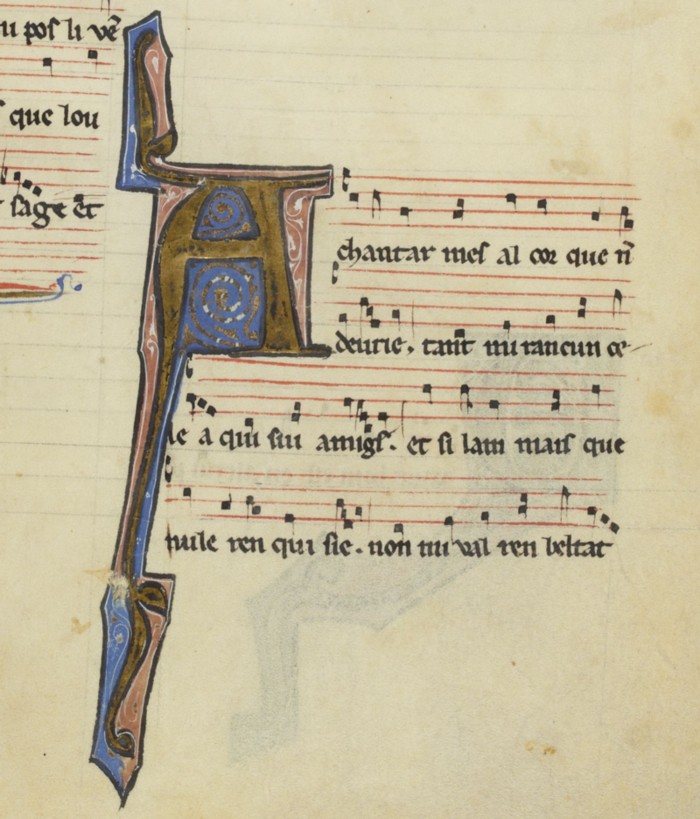

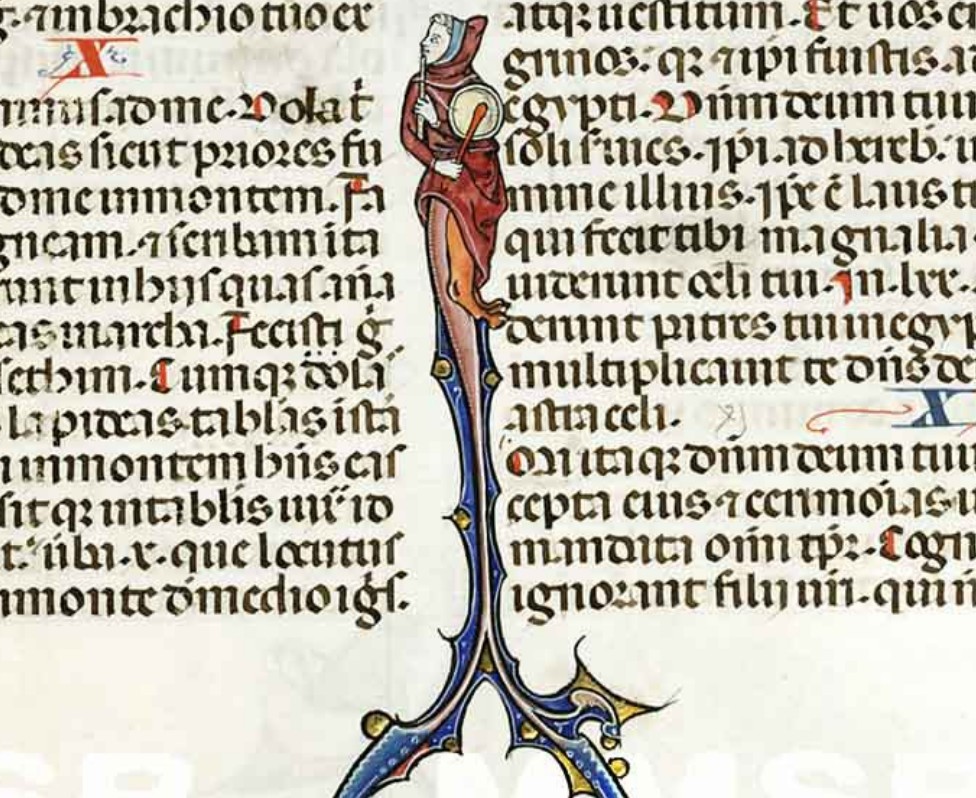

Ofschoon zij over een redelijk adequaat notatiesysteem beschikken,

noteren zij de melodieën waarop hun teksten ten gehore worden gebracht

op schetsmatige wijze. Slechts de modus of toonkleur is afleidbaar. Ritmische en instrumentale aanduidingen ontbreken. De overgeleverde melodieën zijn ver want aan de gregoriaanse en Moorse melodiek.

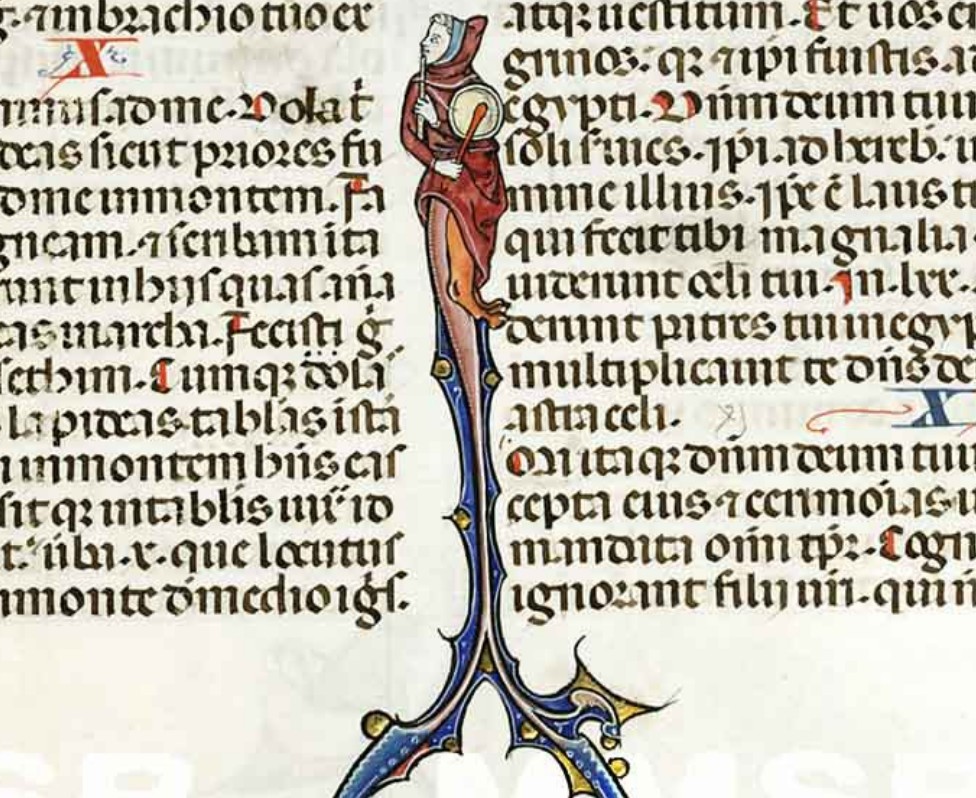

Tijdens voordrachten treden beroepsmusici op, de jongleurs.

Tijdens voordrachten treden beroepsmusici op, de jongleurs.

Veelal voeren zij de composities van de troubadours uit.

Wat

betreft de instrumentale omlijsting van de liederen kunnen we

uitsluitend van hypotheses uitgaan. Een goed voorbeeld van deze traditie

vinden we nu nog in de kunstmuziek van de Arabische, oosterse en, dichter bij huis, Keltische wereld. Deze oraal overgeleverde muziek wortelt in een, in de positieve zin, behoudende cultuur. Wij gaan ervan uit dat de jongleurs

bij deze in essentie eenstemmige muziek een begeleiding improviseerden

(die dus per uitvoering verschilde) ter accentuering van de modus. De

zang wordt hierbij ondersteund door geïmproviseerde voor, — tussen— en

naspelen.

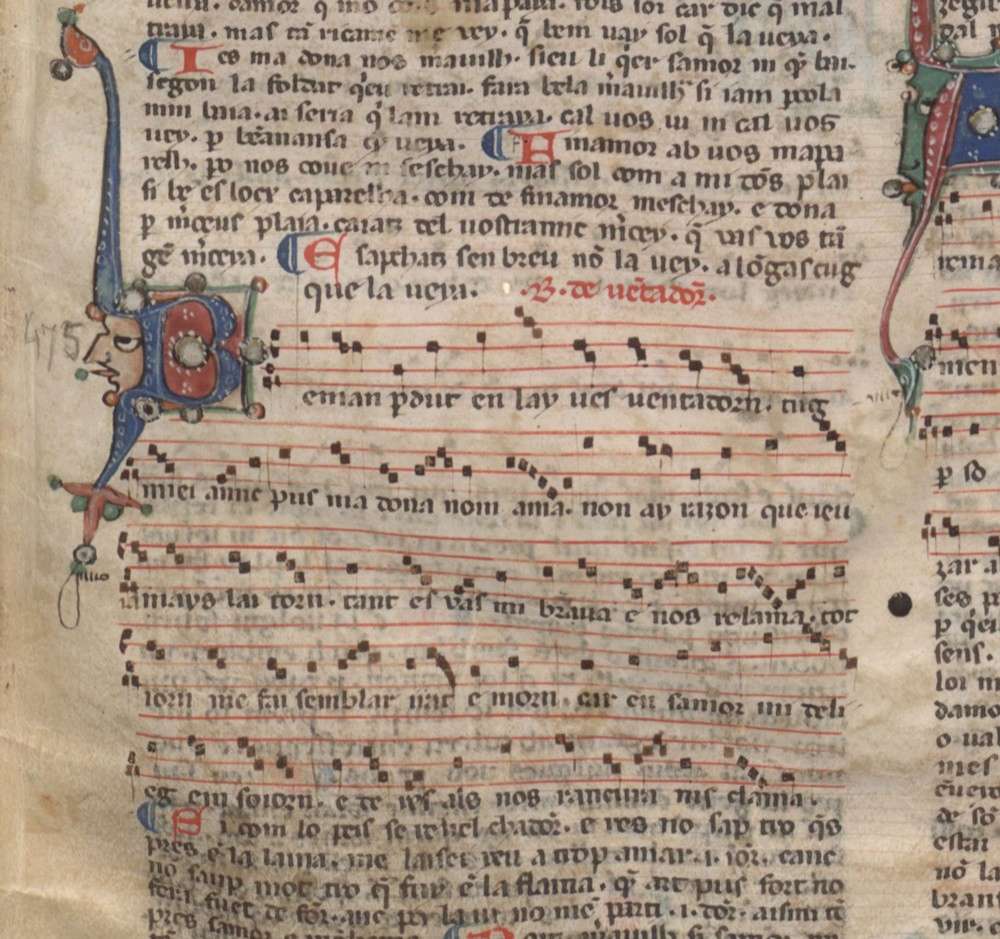

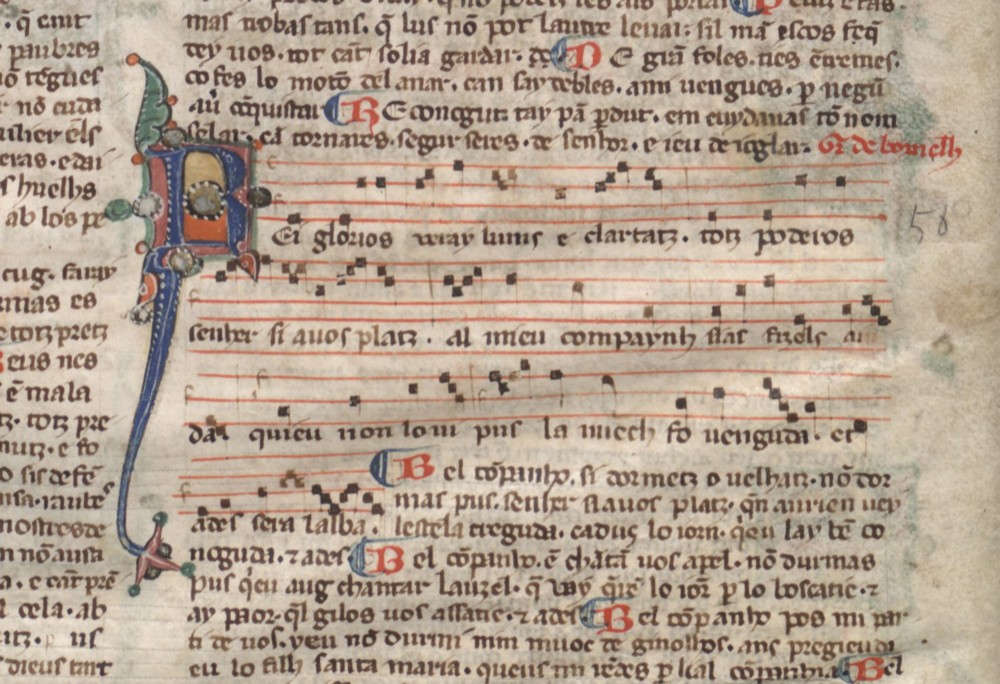

Omdat de orale traditie de basis vormde voor de muziek van de jongleurs, is er geen genoteerde instrumentale muziek uit deze periode overgeleverd. Wel weten we, dat de nota (melodie) van lange dichtvormen als estampie en lai

instrumentaal werd uitgevoerd. Zo schreef ik in de stijl van een ca.

100 jaar later gedateerd manuscript met trouvèreliederen en estampies

(Paris BN fr. 844, 'Le manuscript du Roy') — de oudste bewaard

gebleven instrumentale dansmuziek — over de melodie van 'Be m'an perdut' [6] een nieuwe estampie: de 'Estampida perduda' [3]. De troubadour/jongleur Raembaut de Vaqueiras (ca. 1160-na 1207) deed het anders: hij dichtte zijn 'Kalenda maya' (meilied) op de wijs van een estampie die hij door twee Parijse jongleurs had horen uitvoeren. Op dezelfde manier diende de Provençaalse 'Lai non par' [5] als uitgangspunt voor onze instrumentale lai. Tijdens de uitvoering ervan wordt vrij met het materiaal omgegaan (improvisatie). De tbilet (dubbele vaastrommel) accentueert de Moorse invloed die in die tijd sterk inwerkte op de muziek rondom de Middellandse Zee.

In

schijn een tegenstelling, betekende de uitwisseling tussen kerkelijke

en wereldlijke muziek erg veel. De uitwisseling tussen twee groepen

musici, de clerici en de jongleurs, trachten wij tot uitdrukking te brengen in de improvisatie 'Virgo' [7]. In deze zgn. 'phrygische improvisatie',

die de kleine secunde f—e als centrum heeft, horen we een ritmisch

vrije melodie (op basis van de Indiase raga 'Bhilaskhani todi'), die

zich ontwikkelt tot een ritmische melodie. Deze ritmisering geschiedt in

de vorm van het melisme 'Virgo' , wat als basis dient van de vroegste ritmische meerstemmigheid: de clausulae. Juist deze muziek is zeer interessant: het is mogelijk instrumentale muziek geweest, geïmproviseerd door jongleurs

(ze is veelal tekstloos overgeleverd). Feitelijk betekende ze de eerste

aanzet tot de ritmische meerstemmigheid in onze westerse muziek. De

muziek uit het klooster heeft zeker zijn weerslag gehad op het scheppend

proces van de troubadours. Als adellijke jongeren waren zij voor hun

opvoeding aangewezen op deze kloosters. Na hun opleiding bleven de troubadours 's winters te gast in de kloosters, alwaar ze hun gedichten schreven en liederen componeerden. De improvisatie 'Virgo' is een poging muziek te reconstrueren zoals ze misschien door de jongleurs werd gespeeld in kerk en klooster.

Jankees Braaksma

De liederen

Bij

eerste kennismaking met strofische troubadourliederen is het niet

ongebruikelijk dat ze de vraag oproepen: 'Hoe kan de herhaling van een

melodie interessant zijn?' Men tracht dit probleem op te lossen door

dynamische contrasten te gebruiken (een gekunsteld effect), of door

bepaalde lettergrepen te beklemtonen (wat niet om aan te horen is), of

men probeert er afwisseling in te brengen door het gebruik van

verschillende instrumenten (wat draaglijk klinkt, mits spaarzaam

gebruikt), en men laat strofen weg (denkend dat niemand ze missen zal,

omdat de melodie toch steeds herhaald wordt). Helaas is het resultaat

onbevredigend, zelfs als het mooi klinkt.

Het is dank zij de

liefde voor de poëzie dat men tot een betere uitvoering kan komen — door

weer genoegen te gaan scheppen in het hardop lezen van gedichten, in

het dramatisch horen voordragen van gedichten, in het getroffen worden

door een beeld. Als men een gedicht uit het hoofd leert omdat men het

mooi vindt (en waarom zou men het anders leren?), kan men het gewoonlijk

niet inkorten zonder er afbreuk aan te doen. En waarom zou dat bij

troubadoursgedichten anders liggen? Als men het troubadourslied op de

toehoorder overbrengt door middel van de uitdrukkingskracht van het

gedicht, dan spreekt men rechtstreeks tot de verbeelding. De melodie

wordt flexibel en klinkt steeds weer een ietsje anders. (Als men zo'n

doel voor ogen heeft, biedt La poétique de l'espace van Gaston

Bachelard veel hulp, en het is op zichzelf een prachtig boek!) Een

voorbeeld kan dit verduidelijken. In het vijfde couplet van 'Reis glorios' zegt de spreker:

'Bel companho, pos me parti de vos.

Eu no'm dormi ni·m moc de genolhos,

Ans priei Deu, lo filh Santa Maria,

Que·us me rendes per leial companhia,

Uit

de voorafgaande strofen weten we dat het dageraad wordt (door het in

elk couplet weerkerende 'Et ades sera l'alba'), en men kan zich

voorstellen hoe de vogels wakker beginnen te worden in de schemering. De

spreker heeft gebeden voor het welzijn van zijn vriend. Nu richt hij

het woord tot die vriend en zegt dat hij niet geslapen heeft en aldoor

op zijn knieën is blijven liggen. Kan je de kou voelen van de steen

waarop hij knielt, kan je bijna rillen, en kan je geraakt worden door

zijn droefheid en de inspanning van een hele nacht de wacht houden? Kan

je de vermoeidheid en irrationaliteit oproepen die gepaard gaan met

slaapgebrek? Dit zijn de mogelijkheden, en men kan kiezen welke ervan

men in zijn uitvoering naar voren laat komen.

'Be man perdut'

drukt de smart uit van een man die door zijn aanbedene verbannen is,

omdat zij niet van hem houdt. Hij richt zich niet tot haar, maar klaagt

zijn nood bij zichzelf en zijn vrienden. In een schitterende

opeenvolging van gevoelens vertelt hij hoe hij de vlammen der liefde in

zich voelde branden; hij herinnert zich de schoonheid van haar lichaam

en beklemtoont zijn liefde, of ze die nu wil of niet ('Ik zal een man

voor haar zijn, een vriend, en haar dienen'); tenslotte ishij bereid

zich te troosten met andere vrouwen en de herinneringen aan zijn beste

vrienden. Dit gedicht is net zo vol van zelfbeklag als 'A chantar' , maar het spreekt veel directer aan, omdat het niet zo gelijkhebberig is.

'Be man perdut'

drukt de smart uit van een man die door zijn aanbedene verbannen is,

omdat zij niet van hem houdt. Hij richt zich niet tot haar, maar klaagt

zijn nood bij zichzelf en zijn vrienden. In een schitterende

opeenvolging van gevoelens vertelt hij hoe hij de vlammen der liefde in

zich voelde branden; hij herinnert zich de schoonheid van haar lichaam

en beklemtoont zijn liefde, of ze die nu wil of niet ('Ik zal een man

voor haar zijn, een vriend, en haar dienen'); tenslotte ishij bereid

zich te troosten met andere vrouwen en de herinneringen aan zijn beste

vrienden. Dit gedicht is net zo vol van zelfbeklag als 'A chantar' , maar het spreekt veel directer aan, omdat het niet zo gelijkhebberig is.

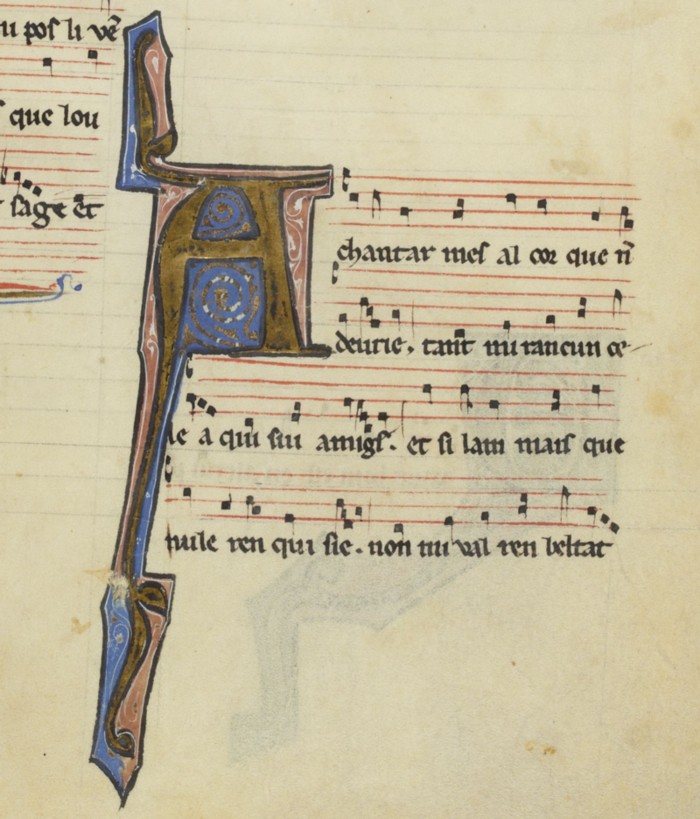

Gelijkhebberigheid voert de boventoon in 'A chantar'

, en in eerste instantie houdt dat gedicht me daardoor op een afstand.

Een vrouw klaagt dat haar geliefde aardig is tegen anderen, maar

beestachtig tegen haar (fier, salvatge), ondanks haar adellijke

afkomst, haar schoonheid en haar karakter: 'Mijn vriend, je bent op dit

gebied zo ervaren dat je toch zou moeten zien wie de beste is'. Maar dat

ziet hij kennelijk niet. In tegenstelling tot hoe we het graag zouden

willen, worden we niet noodzakelijkerwijs begeerd om onze kwaliteiten.

Het is eerder een kwestie van op een bepaald tijdstip 'de ware' voor de

ander zijn (en vice versa): begeerte is grillig en heeft daardoor de

neiging om bij nadere kennismaking te verdwijnen (zij houdt van hem, of

denkt dat ze van hem houdt; hij heeft haar ooit begeerd, maar nu niet

meer). En hoe logisch haar argumenten en haar verdriet ook zijn, toch is

zij natuurlijk een stem die hij niet langer nodig heeft. Dit is een van

de vele interpretaties: men moet zich het gedicht eigen maken. In dit

geval heb ik ervoor gekozen mijn gebrek aan sympathie te overwinnen en

me in haar in te leven, liever dan in hem (in welk geval ik het publiek

had moeten bewegen om kritiek op haar uit te oefenen).

'Reis glorios'

is een waaklied. Een trouwe vriend of dienaar zorgt ervoor dat een

vrijend paartje niet gestoord wordt. In dit lied waarschuwt de vriend

dat de dageraad aanbreekt, maar er wordt niet naar hem geluisterd. De

diepe melancholie van de melodie en de gebeden in het gedicht suggereren

dat het om meer gaat dan slechts de spanning van een door waakte nacht.

De zinger betreurt het, dat hij zijn vriend aan een vrouw verloren

heeft. Misschien valt hier wel een jeugdvriendschap onherstelbaar uit

elkaar.

Consuelo Sañudo

Ensemble Super Librum

Ensemble

Super Librum (Groningen, Nederland), onder leiding van Jankees

Braaksma, bestaat uit internationale specialisten op het gebied van de

middeleeuwse muziek. Vanuit serieuze betrokkenheid bij de interpretatie

van middeleeuwse muziek doen de leden van Super Librum onderzoek op het

gebied van het gebruik van de specifieke zangtechniek, interpretatie van

tekst en

melodiek, speeltechniek van de middeleeuwse instrumenten,

iconografie van de muziekinstrumenten en vooral: de improvisatie. Het

ensemble werkt nauw samen met instrumentbouwers, die reconstructies voor

het ensemble vervaardigen. Sinds de oprichting van Super Librum in 1985

speelt de groep muziek van de 12de tot en met de 15de eeuw.

Ensemble

Super Librum tracht de voorstelling die we hebben van middeleeuwse

muziek te verbreden door een aantoonbare relatie, die er toentertijd

tussen improvisatie en compositie bestond, nieuw leven in te blazen.

Door de aanwijzingen van deze 'verloren gegane traditie' te volgen, het

zgn. 'super librum' — spel (zoals vermeld wordt door de 15de-eeuwse

componist/theoreticus Johannes Tinctoris, die deze speelwijze

prefereerde boven het 'van het blad spelen'), voegt het ensemble een

onmiskenbaar levendig en authentiek aspect toe aan de uitvoering van

middeleeuwse muziek.

Alhoewel er van de super librum—praktijk in

de 12de eeuw geen geschreven voorbeelden zijn overgeleverd,

reconstrueert de groep verscheidene speelpraktijken zoals die door de

jongleurs1 zouden kunnen zijn toegepast. Deze opname tracht ook inzicht

te geven in de zgn. repertoire—uitwisseling tussen troubadours en

jongleurs.

Ensemble Super Librum won de eerste prijs op het

Internationale Concours voor Ensemble Oude Muziek in Amersfoort in 1986.

In 1987 won het ensemble een onderscheiding op het Musicas Antiqua

Concours in Brugge.

De eerste CD, 'Intabulation and improvisation in the 14th century',

is enthousiast door de internationale pers ontvangen.

Ensemble Super Librum is regelmatig te gast op de internationale festivalpodia.

———

1 zie: De jongleurs

De musici

Jankees Braaksma

studeerde blokfluit bij Jeanette van Wingerden; Kees Boeke en Baldrick

Deerenberg op de conservatoria van Groningen en Amsterdam. Hij studeerde

middeleeuwse muziek, met improvisatie als specialisatie aan de Schol

Cantorum Basiliensis in Zwitserland. Als leider van Ensemble Super

Librum verricht hij intensief onderzoek op het gebied van repertoire en

speeltechniek van de blokfluit en het portatief in middeleeuwse muziek.

Hij

doceert blokfluit aan de muziekschool in Groningen en middeleeuwse

muziek aan conservatoria in Nederland en Duitsland. Naast zijn concerten

met Ensemble Super Librum treedt hij regelmatig op als blokfluitist met

repertoire uit renaissance, barok en twintigste eeuw.

Consuelo Sañudo

groeide op in Spanje en begon haar muzikale studie aan het Real

Conservatorio in Madrid. Hierna bracht zij tien jaar door in de

Verenigde Staten. Momenteel woont zij in Keulen. Naast haar concerten

met Ensemble Super Librum treedt zij regelmatig op met Sequentia, Laude

Novella en als solo zangeres in later repertoire.

Ronald Moelker

studeerde blokfluit aan het Rotterdams Conservatorium en het Koninklijk

Conservatorium te Den Haag. Na zijn eindexamen in 1979 heeft hij zich

gespecialiseerd in het bespelen van naar historisch voorbeeld gebouwde

blokfluiten. Zijn muzikale activiteiten strekken zich uit van de

middeleeuwen tot en met de barok. Recentelijk nam hij, eveneens voor

ALIUD, de twaalf fantasieën van G. Ph. Telemann (op voice flute) op. Hij

maakt tevens regelmatig radio opnames. Naast prijzen met Ensemble Super

Librum werd hij in 1987 onderscheiden op het Internationale Concours

voor Ensembles Oude Muziek te Amersfoort.

Instrumentarium

Blokfluiten

naar historische voorbeelden, vervaardigd door Sverre Kolberg,

Sofiemyr, Noorwegen. Gestemd volgens de natuurtoonreeks met c als vierde

toon.

Alt in g' esdoorn — a = 465 (1981) [5]

Alt in g' esdoorn — a = 460 (1988) [2],[7]

Tenor in c' esdoorn —a = 460 (1988) [1],[3],[6],[7]

Bas in F esdoorn — a = 460 (1988) [2],[7]

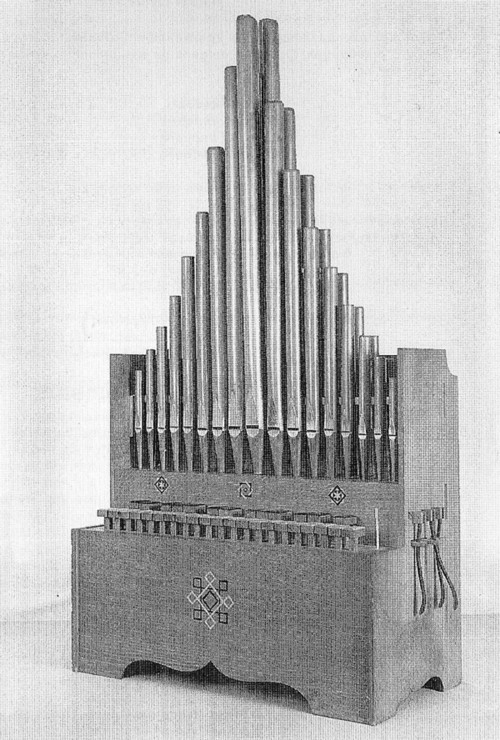

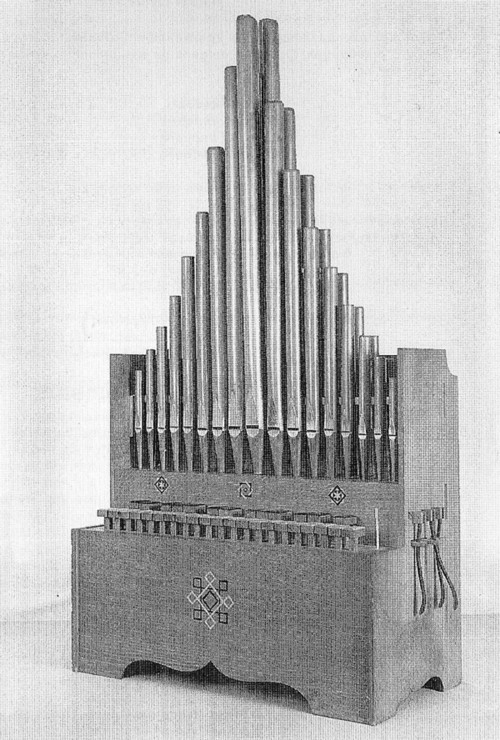

Organetto (portatieforgel) gebouwd door Winold van der Putten, Winschoten, Nederland.

[1],[2],[6],[7]

Reconstructie

naar schilderijen van Hans Memling (1433-1494) in het Museum voor

Schone Kunsten te Antwerpen en Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) in de Sint

Baafskathedraal te Gent.

Pijpwerk naar beschrijvingen van Arnout van

Zwolle (ca. 1450).

95% lood, b' — a''' , a = 460.

Gestemd Volgens Arnout van Zwolle (pythagorisch).

Slagwerk

Tbilet (traditioneel, Tunis, 1990) [5]

Grote trommel (trad., Kenia, 1990) [4]

TROUBADOUR AND JONGLEUR

music from Occitania

For an explanation of the rather sudden rise of the lyrical poetry of the troubadours

at the beginning of the 12th century we have to rely on much guesswork

and many conjectures: about the flourishing of the economy in the South

of present-day France, in Northern Italy and Northern Spain, about

contacts with Arab culture... We are better informed about the decline

of this art. During the first and second crusade against the Albigenses

(1209-1244), an alliance between the Pope and the king of France led to

the conquest of the Provence and adjacent regions, to the burning of

heretics, the murdering of artists and their patrons, and the

incorporation of the territory into the king's realm.

The language of the troubadours was langue d'oc,

a Romance language with elements deriving from Vulgar Latin, Spanish,

French and Arabic. For a long time, the existence of an Occitanian

culture was denied in France. In 1539, the use of langue d'oc was

prohibited by François I. Today, this language is taught again in some

schools in certain regions of Southern France. Several poets, singers

and pop groups use langue d'oc, not only in traditional folk

music, but also in their protests against the French centralist policy

and against environmental pollution, as well as in expressing their

desire for self—government.

The main theme of the lyrical poetry of the troubadours was the fin amors, usually translated as courtly love.

Its focal point was the longing for the absent, virtually unattainable

beloved — virtually unattainable because she (or he) was generally

married to someone else. In this poetry, the fin amors was set in

opposition to the marriage contract based on politico-economic grounds,

which in those days was the rule among the upper classes. We should not

confuse fin amors/courtly love with platonic love; the surviving literature certainly does not warrant that.

From the vida (biography) of Guilhern de Peitieus,

9th Count of Aquitaine (1071-1127), the earliest troubadour known to us

whose poems have survived: "The Count of Poitiers was both one of the

foremost noblemen in the world and one of the greatest deceivers of

women, a knight skilled in the art of handling arms and in the art of

seduction. He was also good at writing poetry and at singing".

Vidas

are biographies of troubadours and trobairitz (female troubadours).

They were usually written down many years after the death of the

troubadour concerned. These texts were recited by the jongleurs as

introductions to the songs they were going to sing.

These vidas

are not very reliable, but they happen to form the sole factual

information handed down to us about the troubadours. The vidas of Beatritz de Dia, Giraut de Borneill and Bernart de Ventadorn run as follows:

'La Comtessa (Beatritz) de Dia

was the wife of William of Poitou and a beautiful, good woman. She fell

in love with Raimbaut d'Orange and wrote many good songs about him'.

'Giraut de Borneill

came from the Limousin, from the region around Exideuil, from a mighty

castle belonging to the Viscount of Limoges (Aimar V, 114 8-1199). He

was a man of low birth, but a well-educated man, thanks to his erudition

and his innate intelligence. He was a better troubadour than any other before or after him; hence he was called the master troubadour,

and is still considered such by those who understand subtle,

well-chosen words of love and wit. He was highly appreciated by

noblemen, experts and women, who gave special attention to the perfect

texts of his songs. His life was arranged in such a way that he taught

literature in school all winter and travelled from court to court all

summer in the company of two jongleurs who sang his songs. He never

married and gave everything he earned to his needy parents and to the

church of the village he was born in; that church was called, and still

is called, the church of St. Gervase' .

'Giraut de Borneill

came from the Limousin, from the region around Exideuil, from a mighty

castle belonging to the Viscount of Limoges (Aimar V, 114 8-1199). He

was a man of low birth, but a well-educated man, thanks to his erudition

and his innate intelligence. He was a better troubadour than any other before or after him; hence he was called the master troubadour,

and is still considered such by those who understand subtle,

well-chosen words of love and wit. He was highly appreciated by

noblemen, experts and women, who gave special attention to the perfect

texts of his songs. His life was arranged in such a way that he taught

literature in school all winter and travelled from court to court all

summer in the company of two jongleurs who sang his songs. He never

married and gave everything he earned to his needy parents and to the

church of the village he was born in; that church was called, and still

is called, the church of St. Gervase' .

'Bernart de Ventadorn

came from the castle of Ventadorn in the Limousin. He was a man of low

descent, the son of a servant who, as furnace-keeper, fired the oven in

which the bread for the castle was baked. He grew up into a handsome and

skillful man. He was very good at singing and "inventing" and became a

courteous and learned man. And the Count of Ventadorn was so charmed by

him, and by his manner of singing and "inventing", that he did him great

honour. Now the Count of Ventadorn had a young, noble and merry wife.

Bernart's songs were to her taste and she fell in love with him and he

with her; so he made her, the love he cherished for her, and her merits

the subject of his poems and songs. Their love lasted long, ere the

Count or anyone else noticed it. And once the Count became aware of it,

he parted his wife from Bernart and had her locked up and watched. The

lady was forced to break off with Bernart and to ask him to depart and

leave the region. He left and went to the Duchess of Normandy, who was

young and had great merit and was skilled in many matters of honour and

of beautiful, laudable language. Bernart's poems and songs were very

much to her taste and she received him very warmly and took him in. He

lived at her court for a long time, fell in love with her and she with

him. While he was with her, the king of England, Henry, took her to

wife, due to which she had to leave Normandy in order to settle in

England. Sad and shaken, Bernart remained on this side of the sea and

betook himself to good Count Raymond of Toulouse, under whose protection

he remained till his death. And because of the pain Bernart had

suffered, he entered the order of Dalon, in which he ended his days.

And

what I, Uc de Saint-Circ, have written about him, was told me by

Viscount Eble of Ventadorn, who was the son of the Viscountess loved by

Bernart' .

The jongleurs

The troubadours were first and foremost concerned with language, with langue d'oc.

Although they dispose of a fairly adequate system of musical notation,

the melodies to which their texts are sung are written down in a very

sketchy manner. Only the mode or tone colouring can be

inferred. Rhythmical and instrumental indications are absent. The

melodies that have come down to us are related to the Gregorian and the

Moorish melodic traditions.

The performers are professional musicians: the jongleurs.

Usually, they sing what the troubadours composed. As regards the

instrumental accompaniment of the songs, we can only guess. A good

present-day example of this tradition we still find in the composed

music of the Arab, the Eastern, and — nearer home — the Celtic

world. This music, handed down orally, has its roots in a culture that

is conservative in the positive sense of the word. We assume that to

this essentially monodic music the jongleurs improvised an accompaniment

(which would therefore differ from performance to performance) in order

to stress the mode. So the singing is supported by improvised preludes,

interludes and postludes. Because oral tradition formed the basis for

the music of the jongleurs, no instrumental music from this period has

been handed down in writing. Yet we do know that the nota (melody) of long verse forms like the estampie and the lai was performed on instruments. Thus, on the melody of 'Be man perdut' I wrote a new estampie: the 'Estampida perduda' [3] in the style of a manuscript of troubadour songs and estampies

dated about one hundred years later (Paris BN fr. 844, 'Le manuscript

du Roy'), the oldest surviving instrumental dance music. The troubadour

and jongleur Raembaut de Vaqueiras (ca. 1160-after 1207) did it the

other way round: he wrote his 'Kalenda maya' (song for the first of May)

to the tune of an estampie he had heard performed by two

Parisian jongleurs. In the same way, the Provençal 'Lai non par' [5]

formed the point of departure for our instrumental lai. In performing it, the material is treated very freely (improvisation). The use of the tbilet (double vase drum) stresses the fact that Moorish influence on Mediterranean music was very strong at the time.

The performers are professional musicians: the jongleurs.

Usually, they sing what the troubadours composed. As regards the

instrumental accompaniment of the songs, we can only guess. A good

present-day example of this tradition we still find in the composed

music of the Arab, the Eastern, and — nearer home — the Celtic

world. This music, handed down orally, has its roots in a culture that

is conservative in the positive sense of the word. We assume that to

this essentially monodic music the jongleurs improvised an accompaniment

(which would therefore differ from performance to performance) in order

to stress the mode. So the singing is supported by improvised preludes,

interludes and postludes. Because oral tradition formed the basis for

the music of the jongleurs, no instrumental music from this period has

been handed down in writing. Yet we do know that the nota (melody) of long verse forms like the estampie and the lai was performed on instruments. Thus, on the melody of 'Be man perdut' I wrote a new estampie: the 'Estampida perduda' [3] in the style of a manuscript of troubadour songs and estampies

dated about one hundred years later (Paris BN fr. 844, 'Le manuscript

du Roy'), the oldest surviving instrumental dance music. The troubadour

and jongleur Raembaut de Vaqueiras (ca. 1160-after 1207) did it the

other way round: he wrote his 'Kalenda maya' (song for the first of May)

to the tune of an estampie he had heard performed by two

Parisian jongleurs. In the same way, the Provençal 'Lai non par' [5]

formed the point of departure for our instrumental lai. In performing it, the material is treated very freely (improvisation). The use of the tbilet (double vase drum) stresses the fact that Moorish influence on Mediterranean music was very strong at the time.

Although

apparently opposed to each other, the interchange between church music

and worldly music was very important. We have attempted to express the

interchange between two groups of musicians, the clerics and the jongleurs, in the improvisation entitled 'Virgo' [7]. In this so-called 'Phrygian improvisation',

centred around the minor second f—e, we hear a rhythmically free melody

(based on the Indian raga 'Bhilaskhani todi') developing into a

rhythmical melody. This increasing rhythmicity takes shape in the

melisma 'Virgo',the basis of the earliest rhythmical polyphony: the clausulae. This music is particularly interesting: it may well have been instrumental music, improvised by jongleurs

(it has generally come down to us without texts). In fact, it was the

earliest form of rhythmical polyphony in our Western music.

It is certain that music from the monasteries had its repercussions on the creative process of the troubadours.

Of noble birth, they depended on these monasteries for their education.

Once this education was finished, the troubadours remained winter

guests in the monasteries, where they wrote their poems and composed

their songs. The improvisation 'Virgo' is an attempt to reconstruct

music as it was perhaps played by the jongleurs in church and monastery.

Jankees Braaksma

Notes to the songs

When

one first encounters strophic troubadour songs, it is not unusual to

answer the question: 'Why would a repeated melody be of any interest?'

One tries to solve the problem by using dynamic contrast (the effect is

artificial), one stresses syllables (unbearable to listen to), one seeks

variety with different instruments (bearable if used in moderation),

and one eliminates a few strophes ('If the melody repeats itself, no one

will miss them,one thinks). Unfortunately the result is unsatisfactory,

even though the sound may be beautiful.

It is through the love

of poetry that one can give a better performance, by reverting to the

pleasure of reading poetry out loud, of hearing it recited dramatically,

of being transfixed by an image. If one learns a poem because one likes

it (why else would one learn it?), one cannot usually shorten it

without damaging it. Why should troubadour poems be an exception?

If

one conveys a troubadour song to the listener through the

expressiveness of the poem, one speaks directly to the imagination. The

melody becomes flexible and never sounds quite the same. (For such an

aim, La poétique de l'espace by

Gaston Bachelard is very helpful, and beautiful in itself!). An example can clarify the above. In the fifth stanza of 'Reis glorios' the speaker says:

'Bel companho, pos me parti de vos.

Eu no'm dormi ni·m moc de genolhos,

Ans priei Deu, lo filh Santa Maria,

Que·us me rendes per leial companhia, ... '

From earlier strophes one has collected that it is dawning (from the obsessive 'Et ades sera l'alba'

in each one), and one can imagine the birds beginning to stir in the

gloom. The speaker has been praying for his friend's safety. Here he

addresses his friend and says he has not slept nor left the kneeling

position. Can one feel the cold of the stone on which he kneels, can one

almost shiver, and can one be reached by his sadness and the strain of

watching for a whole night? Can one recreate the tiredness and

irrationality which accompany sleeplessness? These are the

possibilities, and one can choose which ones will predominate in one's

performance.

'Be man perdut'

is uttered by a man in the throes of exile from his lady, since she

does not love him. He doesn't address her, but complains to himself and

to his friends. In a marvellous succession of emotions he tells how he

found himself in the flames of love; he recalls the beauty of her body

and affirms his love whether she likes it or not ('I will be a man for

her, a friend, and will serve her'); finally he is willing to console

himself with other women and in memories of his dearest friends. This

poem is as self-pitying as 'A chantar'.

However, a lack of righteousness makes it very accessible.

'Be man perdut'

is uttered by a man in the throes of exile from his lady, since she

does not love him. He doesn't address her, but complains to himself and

to his friends. In a marvellous succession of emotions he tells how he

found himself in the flames of love; he recalls the beauty of her body

and affirms his love whether she likes it or not ('I will be a man for

her, a friend, and will serve her'); finally he is willing to console

himself with other women and in memories of his dearest friends. This

poem is as self-pitying as 'A chantar'.

However, a lack of righteousness makes it very accessible.

Righteousness governs 'A chantar'

and initially it distances me from the poem. A woman complains that her beloved is pleasant to others and a beast towards her (fier, salvatge),

in spite of her noble lineage, her beauty and her character: 'My friend,

you are so experienced in this, that you should recognize the finest'.

He doesn't, obviously. Contrary to what we would like, we are not

necessarily desired because of our qualities. It seems more a question

of being 'the one' for another (and vice versa) at a certain point in

time: given its capricious nature, desire tends to disappear on closer

acquaintance (she loves him, or thinks she does; he desired her once and

does no longer). And of course, however logical her arguments and her

pain, she is a voice he no longer needs. This is one of the many

interpretations: one must make the poem one's own. In this case I chose

to overcome my lack of sympathy so as to embody her, rather than embody

him (which would have involved

moving the audience to criticise her).

'Reis glorios'

is a watch—song. A faithful friend or servant makes sure that a pair of

lovers is not disturbed. Here, the friend calls out the warning signs

of dawn, and remains unheeded. The deep melancholy of the melody and

the prayers in it suggest that more is at stake than the strain of

watching all night. The singer laments the loss of his friend to a

woman. Perhaps a childhood friendship is being dissolved irreversibly.

Consuelo Sañudo

Ensemble Super Librum

Ensemble

Super Librum, directed by Jankees Braaksma (Groningen, Netherlands),

consists of internationally acclaimed specialists in the field of

medieval music. Being seriously concerned with the interpretation of

medieval music, the members of Super Librum do intensive research in the

fields of vocal techniques, textual interpretation, playing techniques

of medieval instruments, instrumental iconography and, above all,

improvisation.

The ensemble closely co-operates with instrument builders, who reconstruct period instruments for the group.

Since

its foundation in 1985, the ensemble's repertoire has comprised music

from the 11th century up to the end of the 15th century.

Ensemble

Super Librum seeks to change our perspective on the relationship

between composition and improvisation in medieval music. By following

the principles of the 'lost tradition' of playing 'super librum' (as

stated by the 15th-century composer and theoretician Johannes Tinctoris,

who preferred this manner of performing to playing from a score), the

group adds an unmistakable aspect of liveliness and authenticity to the

performance of medieval music. The reconstruction of these practices

(which were standard, rather than playing from a score) has become one

of the main issues of the ensemble's activities

within the performance of medieval music.

Although

no 12th-century examples of the practice of playing 'super librum' have

been handed down in writing, Ensemble Super Librum has reconstructed

various playing practices that may have been used by the jongleurs2. The present recording

also

tries to offer insight into the matter of the so-called repertory

exchange between troubadours and jongleurs. Following the tradition of

these jongleurs, Jankees Braaksma has written new compositions based on

the original troubadour repertory. In their turn, these 'modern'

compositions yield material for improvisation.

Ensemble Super

Librum was awarded the first prize at the International Early Music

Competition for Ensembles at Amersfoort (Netherlands) in 1986. In 1987

the ensemble won a prize at the Musica Antigua Competition at Bruges

(Belgium).

Its first CD, 'Intabulation and improvisation in the 14th century,' was received with enthusiasm by the international press.

Ensemble Super Librum is a regular guest at international festivals.

———

2 see: The jongleurs

The musicians

Jankees Braaksma

studied the recorder with Jeanette van Wingerden, Kees Boeke and

Baldrick Deerenberg at the conservatories of Groningen and Amsterdam. He

specialised in medieval music, with an emphasis on improvisation, at

the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Switzerland. As leader of Ensemble

Super Librum he does intensive research in the fields of repertoire and

playing technique of both the recorder and the organetto in medieval

music.

He teaches the recorder at the Groningen School of Music, as

well as medieval Music at conservatories in The Netherlands and Germany.

Apart from engagements with Ensemble Super Librum he regularly performs

as a recorder player, with a repertoire encompassing the Renaissance,

the Baroque and the twentieth century.

Consuelo Sañudo

grew up in Spain and studied singing at the Royal Conservatory in

Madrid. After a ten-year sojourn in the USA, she now lives in Cologne,

Germany. Apart from her engagements with Ensemble Super Librum she

regularly performs with Sequentia, Laude Novella and as a solo singer in

later repertory.

Ronald Moelker studied the recorder

at the Rotterdam Conservatory and the Royal Conservatory in The Hague.

Since his graduation in 1979, he has specialized in performing on copies

of historical instruments. His musical activities range from the Middle

Ages up to and including the Baroque. He has recently recorded, also on

the Aliud label, Telemann's twelve fantasies (on voice flute), and he

can regularly be heard on the radio. Besides winning awards with

Ensemble Super Librum he was awarded several prizes at the International

Competition for Early Music Ensembles at Amersfoort in 1987.

The instruments

Recorders

by Sverre Kolberg, Sofiemyr, Norway, after historical examples. Tuned

according to the natural tone scale, with c as the 4th note.

Treble in g'maple — a = 465 (1981) [5]

Treble in g' maple — a = 460 (1988) [2],[7]

Tenor in c' maple — a = 460 (1988) [1],[3],[6],[7]

Bass in F maple — a = 460 (1988) [2],[7]

Organetto (portative organ) by Winold van der Putten, Winschoten, The Netherlands (1983).

[1],[2],[6],[7]

Reconstruction

after paintings by Hans Memling (1433-1494) in the Museum of Fine Arts,

Antwerp, and Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) in Saint Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent.

Pipes after descriptions by Arnout van Zwolle (ca. 1450).

95% lead, b' — a''' — , a = 460.

Tuned according to Arnout van Zwolle (pythagorean).

Percussion

Tbilet (traditional, Tunis, 1990) [5]

Big drum (traditional, Kenya, 1990) [4]

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7038083-1432581856-4789.jpeg.jpg)

'

' Tijdens voordrachten treden beroepsmusici op, de jongleurs.

Tijdens voordrachten treden beroepsmusici op, de jongleurs.

'

' The performers are professional musicians: the jongleurs.

Usually, they sing what the troubadours composed. As regards the

instrumental accompaniment of the songs, we can only guess. A good

present-day example of this tradition we still find in the composed

music of the Arab, the Eastern, and — nearer home — the Celtic

world. This music, handed down orally, has its roots in a culture that

is conservative in the positive sense of the word. We assume that to

this essentially monodic music the jongleurs improvised an accompaniment

(which would therefore differ from performance to performance) in order

to stress the mode. So the singing is supported by improvised preludes,

interludes and postludes. Because oral tradition formed the basis for

the music of the jongleurs, no instrumental music from this period has

been handed down in writing. Yet we do know that the nota (melody) of long verse forms like the estampie and the lai was performed on instruments. Thus, on the melody of 'Be man perdut' I wrote a new estampie: the 'Estampida perduda' [3] in the style of a manuscript of troubadour songs and estampies

dated about one hundred years later (Paris BN fr. 844, 'Le manuscript

du Roy'), the oldest surviving instrumental dance music. The troubadour

and jongleur Raembaut de Vaqueiras (ca. 1160-after 1207) did it the

other way round: he wrote his 'Kalenda maya' (song for the first of May)

to the tune of an estampie he had heard performed by two

Parisian jongleurs. In the same way, the Provençal 'Lai non par' [5]

formed the point of departure for our instrumental lai. In performing it, the material is treated very freely (improvisation). The use of the tbilet (double vase drum) stresses the fact that Moorish influence on Mediterranean music was very strong at the time.

The performers are professional musicians: the jongleurs.

Usually, they sing what the troubadours composed. As regards the

instrumental accompaniment of the songs, we can only guess. A good

present-day example of this tradition we still find in the composed

music of the Arab, the Eastern, and — nearer home — the Celtic

world. This music, handed down orally, has its roots in a culture that

is conservative in the positive sense of the word. We assume that to

this essentially monodic music the jongleurs improvised an accompaniment

(which would therefore differ from performance to performance) in order

to stress the mode. So the singing is supported by improvised preludes,

interludes and postludes. Because oral tradition formed the basis for

the music of the jongleurs, no instrumental music from this period has

been handed down in writing. Yet we do know that the nota (melody) of long verse forms like the estampie and the lai was performed on instruments. Thus, on the melody of 'Be man perdut' I wrote a new estampie: the 'Estampida perduda' [3] in the style of a manuscript of troubadour songs and estampies

dated about one hundred years later (Paris BN fr. 844, 'Le manuscript

du Roy'), the oldest surviving instrumental dance music. The troubadour

and jongleur Raembaut de Vaqueiras (ca. 1160-after 1207) did it the

other way round: he wrote his 'Kalenda maya' (song for the first of May)

to the tune of an estampie he had heard performed by two

Parisian jongleurs. In the same way, the Provençal 'Lai non par' [5]

formed the point of departure for our instrumental lai. In performing it, the material is treated very freely (improvisation). The use of the tbilet (double vase drum) stresses the fact that Moorish influence on Mediterranean music was very strong at the time.