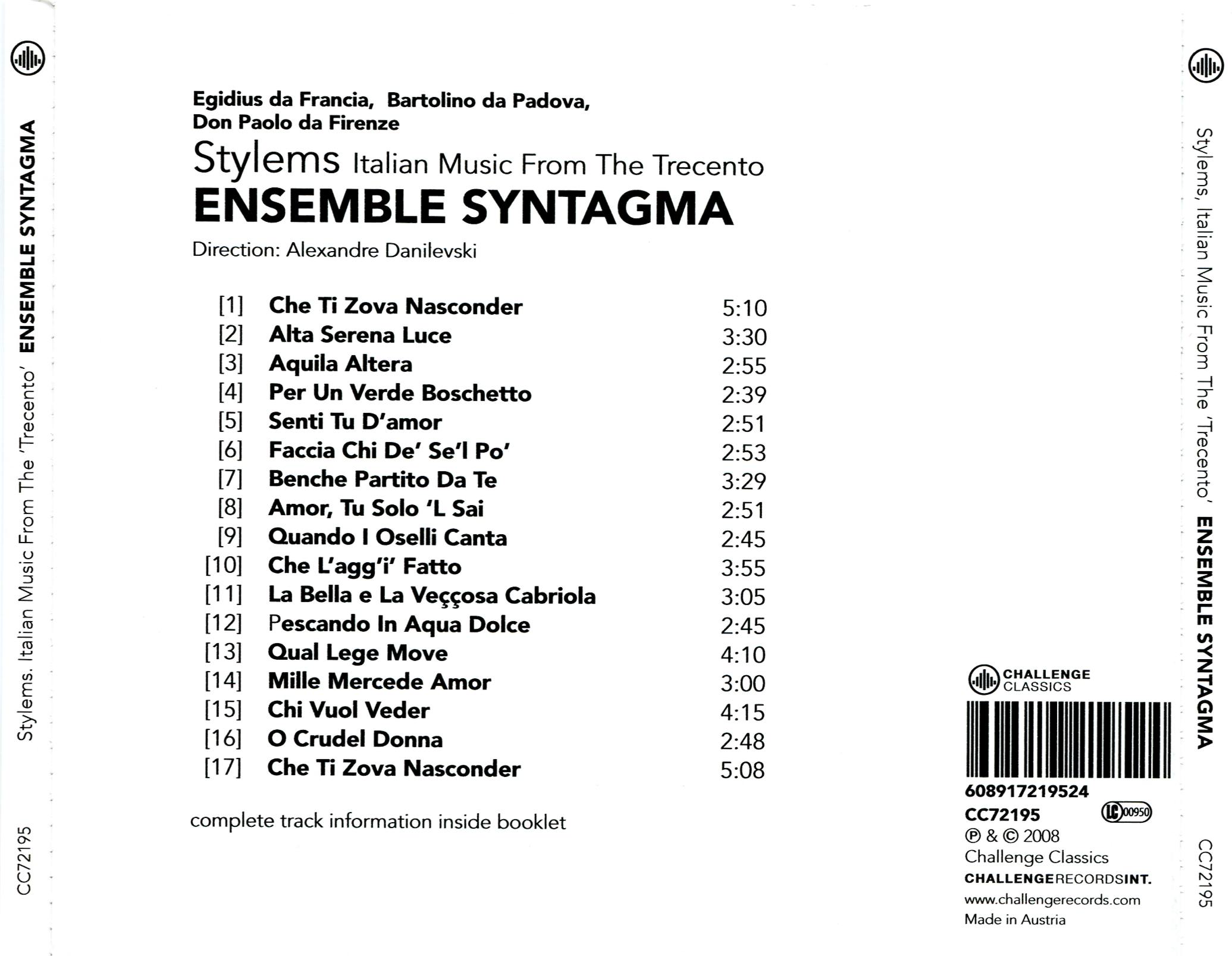

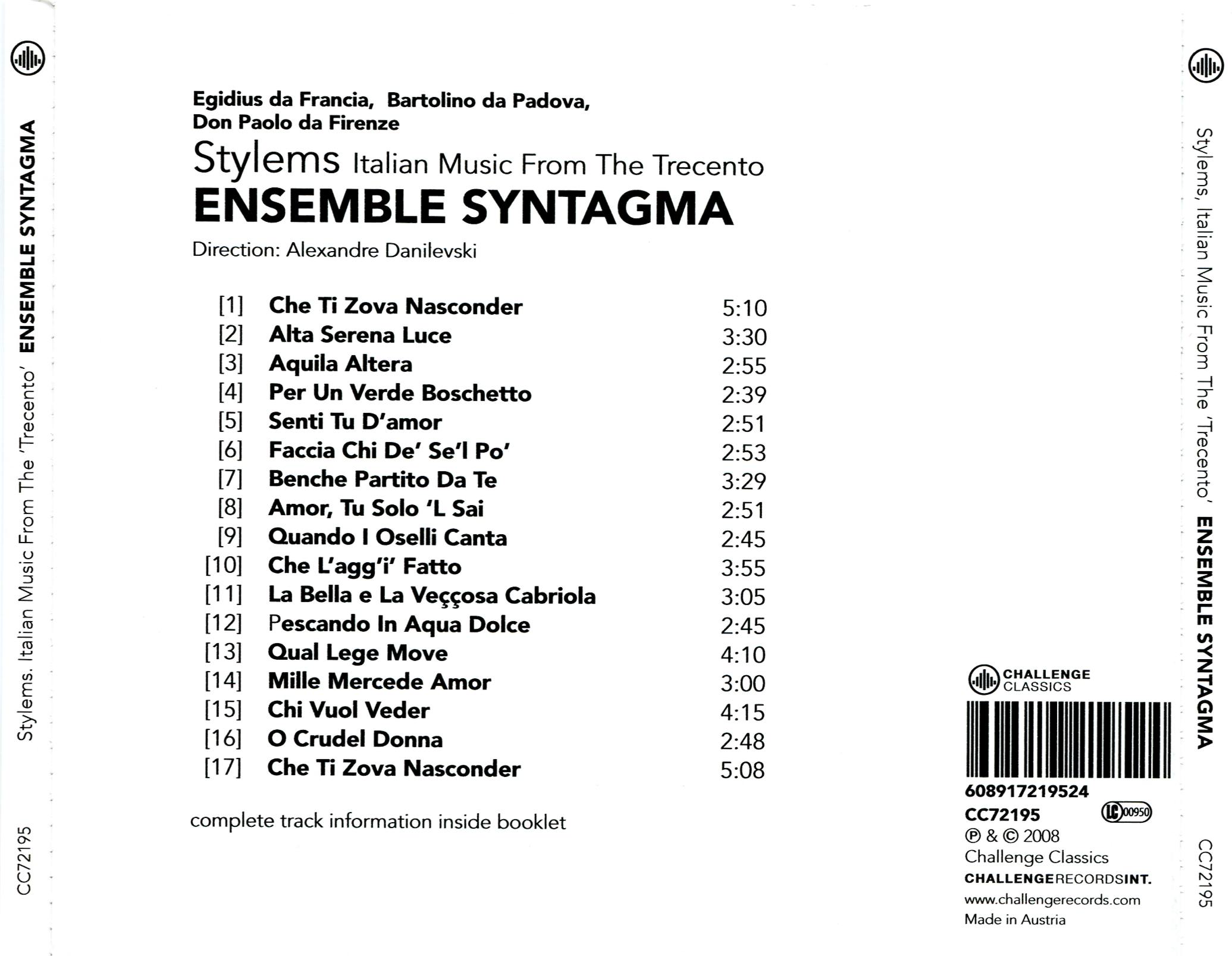

Stylems. Italian Music from the Trecento

/ Ensemble Syntagma

Egidius da Francia | Bartolino de Padova | Don Paolo da Firenze

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7326551-1438965329-4604.jpeg.jpg)

medieval.org

discogs.com

Challenge Classics 72195

2008

1. Che ti zova nasconder [5:10]

ballata | anonymous, 14th century

2. Alta serena luce [3:30]

ballata | EGIDIUS da Francia,

2nd half of the 14th century

3. Aquila altera [2:55]

madrigal | anonymous

4. Per un verde boschetto [2:39]

ballata | BARTOLINO da Padova,

c.1365-1405

5. Senti tu d'amor [2:51]

ballata | DONATO da Firenze,

2nd half of the 14th century

6. Faccia chi de' se'l po' [2:53]

caccia | DONATO da Firenze

7. Benche partito da te [3:29]

ballata | Don PAOLO da Firenze,

c.1355-c.1436

8. Amor, tu solo 'l sai [2:51]

ballata | Don PAOLO da Firenze

9. Quando i oselli canta [2:45]

madrigal | anonymous

10. Che l'agg'i' fatto [3:55]

ballata | Don PAOLO da Firenze

11. La bella e la veççosa

cabriola [3:05] GHIRARDELLO da Firenze,

b.c.1320-25—1362/63

12. Pescando in aqua dolce [2:45]

madrigal | anonymous

13. Qual lege move [4:11]

madrigal | BARTOLINO da Padova

14. Mille mercede amor [3:00]

ballata | EGIDIUS da Francia

15. Chi vuol veder [4:15]

ballata | Don PAOLO da Firenze

16. O crudel donna [2:48]

madrigal | anonymous

17. Che ti zova nasconder [5:08] anonymous

Syntagma

Alexandre Danilevski

Mami Irisawa, soprano

Akira Tachikawa, countertenor

Bernhard Stilz, recorders

Benoît Stasiacyk, percussion

Sophia Danilevski, tromba marina

Alexandre Danilevski, medieval lutes, colichon, fiddle, checker

(clavichord), organ

with the participation of:

Anne Rongy, fiddle

M. Art, harp

Recorders by Bob Marvin (USA, 1992)

Colichon by anonyme (Italie, XVII?)

Lutes, bowed fiddle by Alexandre Danilevski (France, 1995, 1996)

Clavichord by John Morley (UK, 1989)

Portative organ by R.W.C. (UK, 1996)

Executive Producer: Anne de Jong

Recording Producer, Mix & Mastering: Bert van der Wolf

Recorded by: NorthStar Recording Services

Recorded at: Chapelle Saint-Augustin, Bitche, France

Recording dates: 5-7 July 2007

Tracks 3 and 11 were recorded by Maurice Barnish, 15th February 2008

A&R Challenge Classics: Wolfgang Reihing

Booklet Editing: Wolfgang Reihing

Product Coordination: Jolien Plat

Cover Photo: SCALA, Florence

Sleeve Design: Marcel van den Broek

We

are very grateful to Mr Giovanni Carsaniga, Emeritus Professor of

Italian Studies, University of Sydney (Australia), Fellow of the

Australian Academy of the Humanities, for kindly providing us with the

revised poetical texts and their translation.

English liner notes

Stylème, terme employé par les historiens de la

peinture byzantine, désignant des éléments de

style empruntés, incorporés dans un système de

représentation.

Egidius da Francia

Magister Guilielmus de Francia, probablement moine augustin. Son nom

indiquerait des origines françaises, ce qui concorde avec le

style de ses mélodies alla francesca, et c'est tout ce

que l'on peut avancer sur son sujet avec sûreté, nous ne

savons pas si le moine Guilielmus du Ms Squarcialuppi et le Magister

Egidius du Chantilly Codex étaient la même personne.

Bartolino da Padova

Magister Frater Bartolinus de Padu, compositeur italien, appartenait

à l'ordre des Carmélites, au service de la famille

Carrara à Padoue, a probablement vécu à Florence,

en opposition aux Visconti.

Don Paolo da Firenze

Magister Dominus Paulus Abbas de Florentia, le mieux connu de tous

grâce à sa riche carrière diplomatique et

ecclésiastique, appartenait à l'ordre des Camaldules. Il

était également théoricien de la musique.

Anonymous ...

Musique Instrumentale fait ses débuts: la base du

répertoire sont les pièces vocales transcrites pour des

instruments, souvent de façon assez extravagante. L'une des

sources les plus anciennes est le Codex Faenza qui contient des

transcriptions pour les claviers.

Un grand nombre de ces compositeurs étaient dans les Ordres.

Cette appartenance au premier état ne signifiait pas uniquement

l'ascèse. Depuis des siècles, vocation inévitable

pour des cadets, des nobles infortunés et des bâtards

aristocratiques, la vie monastique pouvait encadrer autant les joies

d'esprit que de sens.

La musique des années 1300 attire par la richesse et la

complexité, souvent exquise, des mélodies. Elle

s'éloigne fortement du style des quinze décennies

précédentes, dominées par le génie

français. L'une des avancées

remarquables est la notation mesurée, fraîchement

inventée (mise en théorie dès 1319 par Iohannes de

Muris dans Notitia artis musicae, et en 1322/23 par Philippe de

Vitry dans Ars nova, tandis que les premiers exemples connus se

trouvent dans une copie de Roman de Fauvel, 1317/19). Pour la

musique, c'est une invention aussi grandiose que celle de la roue: elle

offre des libertés inépuisées à ce jour.

Tels explorateurs de nouveaux mondes, les compositeurs se sont

élancés dans des aventures audacieuses. L'utilisation des

mesures élargit infiniment les combinaisons des voix

verticalement et horizontalement. Le style Trecento est souvent vu,

avec reproche, comme une sophistication extrême, comme un jeu

sèchement cérébral. Cependant, au moins dans les

meilleurs spécimens, il a une justification dramatique profonde.

Employé avec mesure et intelligence, il crée l'image

d'objectivité.

Ainsi, dans Que l'agg'i, p.ex., le premier plan est pris

tantôt par la première, tantôt par la

troisième voix ; bien distinctes de caractère, elles

restent en harmonie. La ligne instrumentale est indépendante.

Sans être un accompagnement, elle poursuit sa propre musique,

presque étrangère au contexte, comme si les

événements principaux, dont traitent les voix, se

déroulait sur un fond détaché, tel un tableau avec

des personnages en discussion dans un paysage rempli de bruits de vie

(dans notre interprétation, c'est un chant d'oiseaux).

Les nouvelles perspectives ont mené à l'abandon du

syllabisme: la musique ne dessert plus les nuances d'un mot ou d'une

image poétique, mais crée et poursuit son propre sens et

ses propres nuances. Généralement, ces compositeurs ne

sont plus considérés comme poètes. Si chez les

maîtres de l'Ars Antiqua la musique se pliait à la parole,

chez Guillaume de Machaut les deux éléments sont en

parfait équilibre (au moins, pour ses contemporains), tandis que

chez les Italiens, les textes ne sont plus que prétextes pour la

musique parfaitement émancipée. Comprendre que la musique

peut donner bien plus que «la littérature»

était une révélation, compte tenu de la valeur

hiérarchique supérieure de la poésie.

Malgré les textes le plus souvent banals, cette nouvelle musique

fait découvrir de façon indépendante des aspects

et des profondeurs de sentiments insoupçonnés. Remarquons

que dans De vulgari eloquentia, Dante développe

parallèlement l'idée qu'une poésie médiocre

conviendrait mieux à la musique.

Cette liberté conduit vers une qualité inédite :

l'ironie fine, exprimée par antiphrase : ainsi, le texte de Amor,

tu solo est une lamentation, et la musique, son contraire. Le fait

que les deux voix ici évoluent dans les proportions rythmiques

inégales, renforce le contraste. De cette confrontation nait une

moquerie subtile qui paraît d'autant plus logique que la nouvelle

musique, recherchée et complexe, était en vogue

auprès de la jeunesse dorée (voire

Décaméron, inépuisable source pour tous les

rédacteurs de plaquettes) qui, de tout temps, cultivait ces

qualités précisément, comme expression naturelle

de supériorité. Le souffle d'ironie devient, chez

Ciconia, une de ses plus grandes séductions.

En revanche, Benchè partito et Chi vuoi sont des

miniatures lyriques et expriment une tendresse sincère. Ici, la

polyphonie n'est pas pour attiser un conflit, mais pour ajouter une

sorte de voix intérieure qui exprime un aspect

supplémentaire de l'affection et lui donne du volume.

Au début des années 1300 donc le sentiment de rupture

était général, et justifié, dans toutes les

sphères de la création et du savoir: poésie,

sciences naturelles, pensée philosophique, idées

politiques, peinture, architecture. Pour les arts visuels et la

littérature, ce renouveau est si bien décrit depuis des

siècles que nous sommes tentés d'imaginer le 14-e

siècle italien presque comme la Renaissance dans toute sa

grandeur.

L'idée première de cette

régénération, comme formulée par

Pétrarque, était le retour vers «la pure splendeur

du passé» avec ses lux et sol

(lumière et soleil), soit vers l'antiquité classique, par

opposition à l'usanza moderna, gotica, tedesca - style

des Tramontani (gens d'au-delà des Alpes) qui avaient

imposé nox et tenebrae.

Pour les arts figuratifs, les modèles antiques étaient

assez facilement accessibles et sont connus. Qu'en est-il pour la

musique ? La musicographie de Trecento est immense. La dose de la

monophonie précédente et l'apport de nouvelles

idées proposées par des intellectuels français

sont finement analysés. Pourtant un point demeure encore

inconsidéré.

Au quatorzième siècle, les Italiens continuaient à

s'instruire auprès des Grecs de Byzance, héritiers

directs de la plus vieille civilisation européenne et qui, par

ailleurs, s'auto-définissaient comme «Romains».

Jusqu'à la chute de Byzance, l'espace culturel

gréco-romain, y compris musical, se maintient sans interruption.

L'illustration et le développement de cette thèse a

besoin d'études approfondissant le degré de cette

influence.

Emilia Danilevski

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7326551-1438965329-4000.jpeg.jpg)

Styleme, term used by historians of Byzantine painting for borrowed stylistic elements incorporated in a work of art

Egidius da Francia

Magister

Guilielmus de Francia, probably an Augustinian monk. His name suggests

he was of French origin, which fits well with the style of his alla francesca

tunes; and that is all that can be said of him with certainty: we do

not know if the monk Guilielmus of the Squarcialupi Codex and Magister

Egidius of the Chantilly Codex were the same person.

Bartolino da Padova

Magister

Frater Bartolinus de Padua, an Italian composer and a member of the

Carmelite order in the service of the Carrara family in Padua, probably

lived in Florence.

Don Paolo da Firenze

Magister

Dominus Paulus Abbas de Florentia, well-known for his glittering career

as a diplomat and cleric, belonged to the Camaldolese order. He was also

a theoretician of music.

Anonymous...

Instrumental Music

was just beginning: the basis of the repertoire is vocal pieces

transcribed for instruments, often in quite an extravagant style. One of

the oldest sources is the Faenza Codex which includes transcriptions

for keyboard.

A great many of the composers were members of

religious orders. But membership of the first estate did not always mean

austerity. The monastic life had for centuries been an unavoidable

career choice for younger siblings and destitute or illegitimate members

of the nobility, and often offered much to appeal both to the mind and

the senses.

The music of the 1300s is attractive for the

inventiveness and often exquisite complexity of its melodies. It is a

marked departure from the style of the previous 150 years, which were

dominated by the French school. One

of its remarkable advances was

measured notation, a recent invention (with the theory set down as early

as 1319 by Johannes de Muris in Notitia artis musicae, and in 1322-23 by Philippe de Vitry in Ars nova, while the first known examples appear in a copy of the Roman de Fauvel,

1317-19). To the world of music this was akin to the invention of the

wheel: it offers a freedom whose full potential has yet to be exploited.

Like the explorers of new worlds, composers embarked on bold

adventures. The use of mensuration infinitely enlarges the possible

combinations of voices, both vertically and horizontally. The Trecento

style is often criticised for being excessively sophisticated, dry and

cerebral. And yet, at any rate where its best examples are concerned, it

is thoroughly justified for dramatic reasons. Used intelligently and

with moderation it creates the very image of objectivity.

Thus in Que l'agg'i,

for instance, the foreground is sometimes occupied by the first voice,

and sometimes by the third; though quite distinctive in character, they

remain in harmony. The instrumental line is independent. It is not an

accompaniment but goes its own musical way, almost without reference to

the context, as if the main events discussed by the voices were

unfolding against an impartial background, as in a painting where

characters converse in a landscape full of the sounds of life (in our

interpretation, the sound of birdsong).

As a result of these new

perspectives, syllabic word-setting was abandoned: music was no longer

there to serve the subtleties of a word or a poetic image, but instead

created and pursued its own meaning and nuance. By and large, these

composers were no longer regarded as poets. While music in the hands of

the masters of Ars Antiqua was subservient to the text, in those of

Guillaume de Machaut the two elements were in perfect balance (at least,

they were to his contemporaries), whereas with the Italians text came

to be a mere pretext for fully emancipated music. Realising that music

could deliver far more than 'literature' came as a revelation, in a

world where poetry was hierarchically superior. In spite of often quite

banal texts, the new music, by and of itself, brings to light hitherto

unsuspected facets and depths of feeling. It is worth noting that in De

vulgari eloquentia Dante was at the same time developing the notion that

music was better served by poetry that was mediocre.

This freedom resulted in a novel quality: a fine sense of irony, expressed through antiphrasis. Thus the text of Amor, tu solo

is a lament, and the music is its opposite. The fact that here the two

voices proceed in different rhythmic subdivisions reinforces the

contrast. This clash creates a subtle form of mockery, which is entirely

consistent with the fact that the new music, in all its elaborate

complexity, was in vogue with the jeunesse dorée of the age (see the Decameron,

an inexhaustible resource for writers of CD notes) who have always

cultivated such qualities as the natural mark of their superiority. In

Ciconia this hint of irony becomes a highly attractive feature.

On the other hand Benchè partito and Chi vuol

are lyrical miniatures and express a genuine tenderness. Here the

polyphony does not set up a conflict but adds a sort of inner voice,

expressing an additional aspect of the emotion and giving it weight.

In

the early 1300s there was a widespread, and justified, sense of

breaking with the past in every area of the arts and sciences: poetry,

natural science, philosophy, political theory, painting and

architecture. In the visual arts and literature, this renewal has been

so well described for so long that we are almost tempted to think of the

Italian 14th century as alone embodying the whole Renaissance.

The initial idea in this act of regeneration, as formulated by Petrarch, was a return to 'the splendour of the past' with its lux and sol (light and sunshine). In other words, to classical antiquity from the usanza moderna, gotica, tedesca, (modern, Gothic or German idiom) that was the style of the Tramontani — the people beyond the Alps — and the nox and tenebrae (night and darkness) that they had imposed.

In the figurative arts the models of antiquity were easily accessible and well-known. But what was the situation with music? The

musicography of the Trecento is immense. The prevailing monophony of

the earlier period and the new ideas proposed by the French theorists

have been analysed in detail. But one point has been overlooked. In the

14th century the Italians were continuing to learn from the Greeks of

Byzantium, the direct heirs of the oldest civilisation in Europe, who

actually thought of themselves as 'Romans'. Graeco-Roman culture,

including its music, was maintained without interruption until the fall

of Byzantium. This theme needs further development.

Emilia Danilevski

Translation: Edward Seymour

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7326551-1438965329-4604.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7326551-1438965329-4000.jpeg.jpg)