medieval.org

Olive Music om 005

2005

medieval.org

Olive Music om 005

2005

1. Bonjour, bon mois (rondeau) [4:08]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay

Further sources in München and Paris

2. Las, que feray? (rondeau) [5:27]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay

Further sources in Escorial and Straßburg (lost)

3. J'ai mis mon cuer (ballade) [2:04]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay

Further source in Venice

Akrostichon: JSABETE

4. Mon cuer me fait (rondeau) [5:08]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay conposuit

Akrostichon: MARJA ANDREASQ[ue]

5. Hélas mon deuil (virelai) [5:34]

Oporto, Biblioteca Pública, Municipal, Ms. 714

Dufai

6. La belle se siet (ballade) [1:13]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

G. du fay

Further sources in Bologna, Paris and Namur

7. Quel fronte signorille (rondeau) [3:28]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay

Rome conposuit

8. Helas, ma dame (rondeau, instr.) [3:41]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

(text incomplete)

G. dufay conposuit

9. Je languis en piteulx martire (ballade) [7:59]

Trento, Museo provinciale d'Arte, Ms. 1379

Dufay

10. Ce jour de l'an (rondeau) [2:24]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay

11. Dona i ardenti rai (rondeau) [2:33]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay

12. Adieu ces bon vins de Lannoys (rondeau) [4:21]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

G. dufay 1426

13. C'est bien raison (ballade) [10:55]

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can. Misc. 213

Guillermus dufay

TETRAKTYS

Jill Feldman, soprano

Kees Boeke, vielle, flustes

Maria Christina Cleary, harpe

Jane Achtman, vielle

Viellas/fiddles: Fabio Galgani, Massa Marittima, Italy

Flutes: Luca de Paolis, l'Aquila, Italy

Harp: Winfried Görge, Berlin

Diapason: a'=523 Hz

Temperament: pythagorean

Recorded: 2-4 May 2004

at the Pieve di San Giovanni Battista a Petrolo Galatrona, Arezzo, Italy

Production:

Kees Boeke | Mario Martinoli

Recording engineer: Matteo Costa

Pre-editing: Kees Boeke

Digital editing: Matteo Costa

Liner notes: Laurens Lütteken

Design and lay-out: Artwize Amsterdam

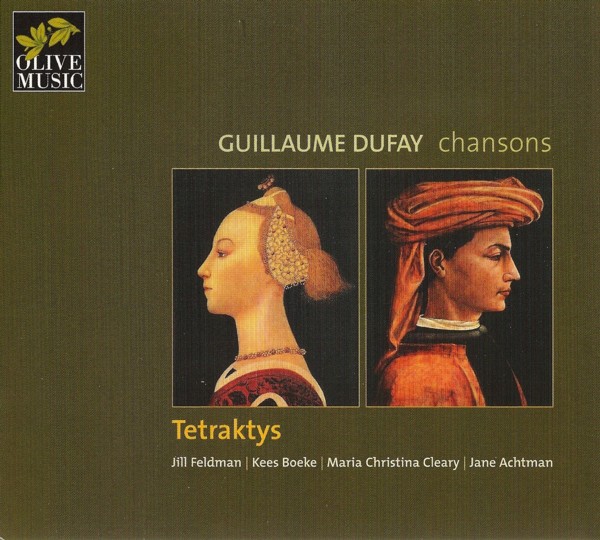

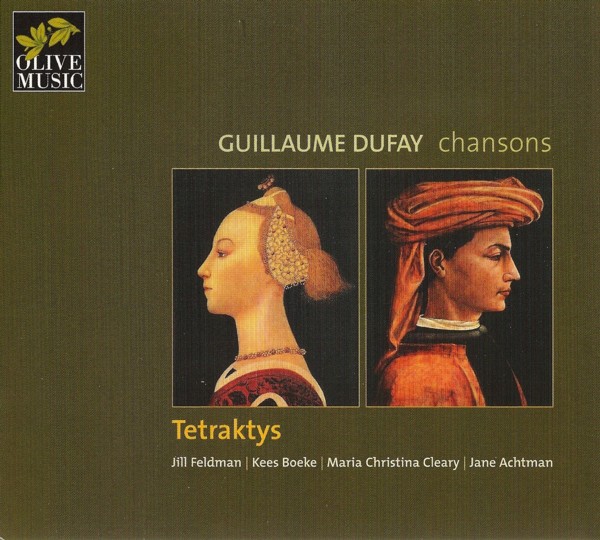

cover illustration:

Paolo Uccello (1397-1475)

Portrait of a young man ca. 1450

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Chambéry

&

Portrait of a Lady

(supposedly Elisabetta di Montefeltro, wife of Roberto Malatesta) ca. 1450

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ⓟ Olive Music 2005

© Kees Boeke & Olive Music 2005

COMPOSING BETWEEN STANDARDIZATION AND INDIVIDUALIZATION

Guillaume Dufay's Chansons

Guillaume

Dufay, the radiant and widely travelled musical authority of his

century, occupied himself during his lifetime not only intensively with

religious music but also with secular composition, and this quite

independently from his respective positions of employment. Moreover, in

the secular repertoire, he was confronted from the start with conditions

that fundamentally did not change until his death, and that therefore

differ characteristically from the two other main genres that were

substantially modified and developed by him: the motet and the newly

emerging cyclic mass ordinary. The secular music of the 15th century was

the only field in polyphonic compositional praxis that possessed clear

formal structures. Whereas mass and motet differed in that new

compositional relationships had to be constituted from work to work,

secular music showed a clear structure, based on the repetition of

sections. These structures, however, were not independent but were

derived from the patterns given by the underlying organization of the

strophic text. Still, for the first time in polyphonic music, this

provided a model that permitted a differentiated intrinsically musical

form.

The first examples stem from the first decades of the 14th

century, when the lyrical genres found their relatively precise

definitions that became the patterns for the music. These polyphonic (as

a rule 3-part) musical settings had to exactly mirror the formal

construction of the poetry, and were for this reason called “formes

fixes”. Essentially, we distinguish three strophic forms of varying

degrees of complexity: Rondeau, Ballade and Virelai or Bergerette. As a

rule, the principle is that, apart from a refrain, single verses with

identical text and music, or respectively, verses with different text

but identical music are performed.The disposition and succession of

these verses together with the(ir) metre then yield the respective

genre.

However, the far-reaching standardization of the “formes

fixes” did not only concern the outer structure. Basically, since the

14th century there were further prerequisites connected to them that, at

least during Dufay's lifetime, did in principle not change and were

valid throughout Europe. For one, the text was in the French language,

which was not only obligatory in Burgundy, France and Savoy, but equally

in the area of what is today's southern Germany, and Switzerland, as

well as at the courts and “signorie” in northern and central Italy, with

the inclusion of the papal state. Italian, German, Spanish and Flemish

texts always constituted an exception and only developed a truly

autonomous and continuous tradition from 1500 onwards. On the other

hand, and this was the second important prerequisite, secular music

produced a type of composition that is emphatically distinct from the

motet or the mass, and at first glance seems much more “modern”. It is

called “cantilena” or treble-dominated style that as a rule consists of a

sung upper part with two untexted, and therefore probably instrumental,

lower parts, in the way as it has been realised in this recording. The

mass or motet, on the contrary, is made up of a texture of, as a rule,

four equally important voices with a cantus firmus in the tenor part.

The multiple texting of voices (like in Dufay's Ce jour de l'an) or four-part writing (as in Mon cuer me fait)

remained an exception. These prerequisites were binding until the end

of the 15th century. Only then were the “formes fixes” replaced by free

forms, because their plain structure was no longer perceived as a

quality but rather as an impediment: on one side the unrestrained French

chansons, on the other that multitude of Italian text-declamatory forms

that would eventually merge into the madrigal.

As distinct from

the compositions of his slightly younger contemporaries, Dufay's

chansons were written down in manuscripts that normally also contained

liturgical repertoire and motets. Moreover, the transmission of his

works, although in numbers for which there is no parallel in the 15th

century, is altogether problematic. This is because, apart from one

possible exception, not a single one of these manuscripts originates

from the immediate vicinity of the composer. Almost all of them were

produced before 1450, mostly in northern Italy, and were not intended

for performance. The most famous of these (which is also the most

important for the pieces on this recording, and at present is in the

Bodleian library in Oxford) was compiled in 1436, and probably comes

from Venice, although our composer never held a position there. This

signifies, in terms of Dufay's Chansons, an aggravating deficit: no

direct sources remain from any of the many locations of activity of the

composer. Most of his works are only vaguely datable, and from the

second half of his life no chansons whatsoever survive, although it is a

known fact that he composed secular works also during his permanence in

Cambrai. The manuscripts that were compiled there were destroyed at the

latest during the iconoclasms of the French revolution, when the

cathedral itself also was razed.

Under these circumstances, it is

all the more astonishing that so many of Dufay's chansons have actually

survived, although they irrevocably only allow insight into the

creativity of the young and middle-period composer. At least, in the

preserved works, we rarely meet with uncertainties as regards authorship

and philological consistency. In addition, there is a clear

hierarchical preference: foremost are the French works, with the number

of remaining Rondeaux (around 60) six times that of the Ballades (around

10), and the slightly old-fashioned Virelai (4) hardly playing a role

anymore. The few Italian songs (8), on the other hand, have a particular status as they form an isolated

group of intricately constructed pieces in a predominantly anonymous and

unpretentious repertoire of Italian compositions before 1470. The 14

works chosen for this recording — about one sixth of all the chansons by

Dufay that have been preserved — reflect this hierarchy in a nutshell:

nine Rondeaux (of which two with Italian text), four Ballades and one

Virelai.

It is in Dufay's songs that, for the first time in the

realm of secular music, we may discern a reflected treatment of the

fixed norms of the genre, and in this they distinguish themselves

completely from the productions of his contemporaries. On the one hand,

all songs, with few exceptions, respect the canon of courtly love, i.e.

maintain the laws of the “formes fixes”, without significant variations.

At the same time, however, they achieve a maximum in compositional

procedures within these boundaries, and as such they assume the status

of far-reaching exploration of the “formes fixes” themselves, as it

were, on a meta-level of the compositional discourse. In this sense, the

compositional individualization does not signify a breaking with the

standard rules, but is rather accomplished by an extremely

differentiated procedure of reflection and commenting that takes on a

new form from work to work. Thus they mark the beginning of a new era in

music in two ways: on the one hand, they refer to the normative

consolidation of the relationships between genres, and those

relationships we encounter actually for the first time only in the 15th

century. On the other hand, each single work acquires, at best, the

status of a productive, individual and therefore unique argumentation of

these norms.

The techniques that Dufay uses to this end know

hardly any limits in their multiplicity and abundant fantasy. Already in

a Rondeau like Adieu ces bons vins this becomes manifest,

especially since this is on the surface a rather conventional piece. lt

is in 3 parts, in “Cantilena” style. lt has an instrumental introduction

and an instrumental epilogue, the piece comes tonally full circle, and

the single verses of the text are clearly separated. In the manuscript,

the work is even, exceptionally, dated. lt is 1426, and we hear about

the singer's probably only fictitious farewell to Laon, since there is

no proof that the composer was actually ever there. Consequently the

piece belongs more likely at the court of the Malatesta. In the inner

structure of this “standard” song, though, the composer shows his

abilities in musical differentiation, for example in the four different

and most significant settings of the word “Adieu”. Or, in the refined

dovetailing of the three voices, and the declamatory rendering in

descending melodic lines at the end of the second, respectively of the

last verse.

All these courtly chansons were written on

commission. In some of them the name of the patron is hidden in an

acrostic (the first letters of each text line put together), as in Mon ruer me fait, an homage to a certain Maria and a certain Andreas whose identity up until now could not be successfully established. In C'est bien rayson,

dated 1433 and written in praise of Niccolò III d'Este of Ferrara, the

name of the prince is even emphatically mentioned at the very end of the

piece and appropriately presented. The delight of the public at court

however was perhaps less ignited by searching for such hidden or

representative homages than by perceiving the finesse in the

compositional inner structure. These differ from work to work, and in

them the composer shows what he is worth. In J'ay mis mon ruer,

Dufay experiments with suggestive, declamatory text portrayal and at the

same time presents patroness Elisabetta Malatesta da Rimini (JSABETE)

in an acrostic. In Je languis, a widely expanded Ballade, the

composer tries the opposite: relatively little text in soaring melodic

lines. In the witty New Years song Bon jour, bon mois, both outer parts form a canon that constantly is broken up, and in La belle se siet

the dialogue in the text becomes the starting point for a highly

virtuosic exchange between the voices. Finally, in the two Italian

pieces, and especially in Quel fronte signorille (probably

written at the papal court), the composer exploits both texted outer

voices for a compact rendering of the words, without falling into

rhetorical or declamatory style.

In all this there is one thing

that plays only a minor role, an aspect that would excite the main

interest of composers after Dufay's death: the emotional musical

interpretation of single words in the text. We see this aspect in

Dufay only as an exception, which however at the same time can be

considered one of the most spectacular of the entire 15th century: In

the Rondeau Hélas mon deuil, of which the text remains

incomplete, the composer endeavours an expressive text interpretation

exemplified by a refined chromatic texture, bold tonal treatment

(beginning and end differ in tonality), a breaking down of the hierarchy

between the voices and the inclusion of change of mensuration in the

process. Thus in a way, he spreads wide out all compositional parameters

that are not normally at his disposal, in order to try to make the

listener participate in the “complainte” with the help of music, to move

and overwhelm him with song.

Nevertheless, also Hélas mon deuil

is merely embedded in a colourful spectrum of compositional procedures

of which around 1450 it was not yet clear, which one would eventually

succeed and which one would not. Thus the rules of the “formes fixes”

become here a framework for individual musical experiments that do not

question coherent relationships but present them to make them the object

of observation and contemplation. In this manner, and this is unique in

the context of the 15th century, Dufay's works emphatically establish

the consistency of the genre, and at the same time put it in question.

Probably for the last time, they obey, in the structural treatment of

the text, modes of thought that still belong to the middle ages. On the

other hand, and probably for the first time in music history, they

reveal, in the conscious and critical consideration of the norms of the

genre, something like a productive historical thinking in terms of

musical composition. Therefore Dufay's chansons stand at the beginning

of a new, epochal context, definable as “change” or “modem times”, last

but not least from the point of view of the composer himself.

Laurenz Lütteken

translation: Kees Boeke, Robert Claire

GUILLAUME DUFAY

Just before 1400

Born, perhaps in Cambrai, as the son of Marie Dufay, father unknown.

1409-14

Puer altaris, afterwards clericus at Cambrai cathedral.

1414-17

In the entourage of cardinal Pierre d'Ailly during the Council of Constance.

1418

Ordination to sub deacon at Cambrai.

1419-26

Singer in the court chapel of the Malatesta family in Rimini and Pesaro.

1425/26

Travel to the Peloponnesos, and to Patras.

1426-28

In the service of Cardinal Louis Aleman in Bologna.

1428

Ordination to priest.

1428-1437

Singer

in the chapels of Pope Martin V. and Pope Eugene IV, from c.1431 as

maestro di capella, first in Rome, later (1436/37) in Florence.

1433-35

Maestro di capella at the court of Duke Amadeus VIII of Savoy in Chambéry.

1436

Nomination

as canon at the Cathedral of Cambrai (already1431 prebends in Tournai,

Lausanne and Bruges, 1433 in Cossonay,1434 in Geneva).

1437

Legal studies, probably at the university of the Curia.

1438-39

Representative of the Chapter of the cathedral of Cambrai during the Council of Basle.

1439-52

Canon at the Cathedral of Cambrai,

1446 also Canon at Ste.Waudru in Mons;

Travels to Bruges (1442 and 1443), to Brussels (1449) and to Italy (1450).

1452-58

Again maestro di capella at the court of Savoy in Chambéry.

1458

Definitive return to Cambrai; ordering and collecting of his works in systematically arranged manuscripts (all lost).

1460-74

Composition

of the great Cantus firmus Masses, of the 'Ave regina celorum' (1464),

the Requiem (1470, lost) and other liturgical, but probably also secular

works, among which a comprehensive monodic Marian liturgy; extensive

contact with important European courts.

27.11.1474

Dies in Cambrai.