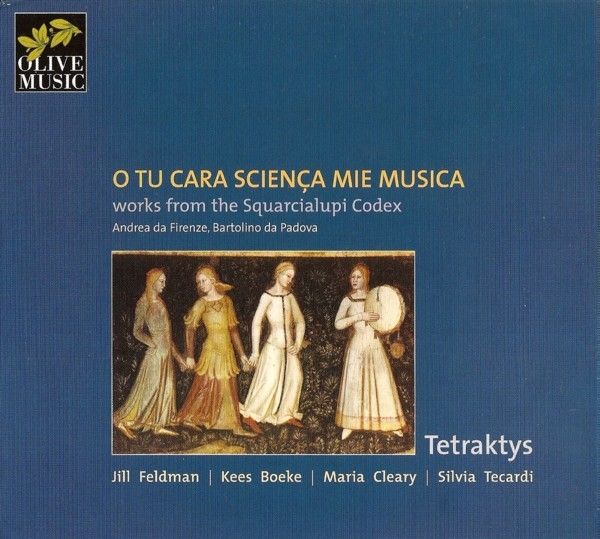

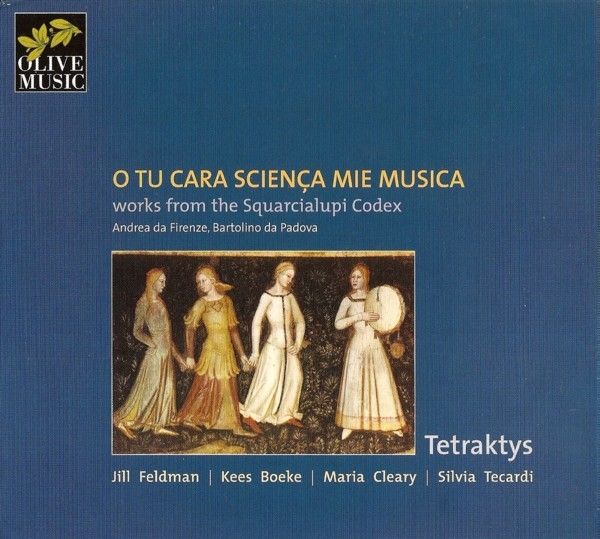

O tu cara sciença mie musica / Tetraktys

Works from the Squarcialupi Codex | Andrea da Firenza · Bartolino da Padova

medieval.org

Olive Music OM 007

2005

Giovanni da CASCIA

(fl. mid 14th c.)

1. O tu cara sciença mie musica [4:12]

madrigale a 2

Gherardellus de FLORENTIA

(c. 1320/25—1362/63?)

2. Una colomba [5:13]

madrigale a 2

Laurentius de FLORENTIA

(d. 1372/73)

3. Dolgomi a voi maestri [3:36]

madrigale a 3

4. I'credo ch'i' dormia [5:01]

madrigale a 2

Vincenzo da RIMINI

(fl. mid 14th c.)

5. In forma quasi [1:51]

caccia

Nicolaus de PERUGIA

(fl. 2nd half 14th c.)

6. O sommo specchio [3:27]

madrigale a 3, instrumental

Bartolino da PADOVA

(fl. c. 1365—c. 1405)

7. Non correr troppo [6:24]

ballata a 3

8. Ricorditi di me [2:22]

ballata a 3, contratenor from Codex Mancini, Lucca;

in Squarcialupi-Codex a 2

9. Inperial sedendo [5:48]

madrigale a 3, version from Codex Mancini, Lucca;

in Squarcialupi-Codex a 2

10. La doulse çere [3:05]

madrigale a 2, instrumental

tabulature from Codex Faenza (harp)

Andreas de FLORENTIA

(c. 1350—c. 1415)

ballate a 3

11. Pianto non partirà [5:42]

12. Sotto candido vel [3:04]

13. Donna, bench'i mi parta [4:00]

14. Presunzion da ignorança [3:03]

15. Perché veder non posso [2:18]

instrumental

16. E più begli occhi [4:54]

Sandra

17. Dè, che farò, signore? [3:15]

18. Non più doglie ebbe Dido [5:59]

TETRAKTYS

Jill Feldman, soprano

Kees Boeke, flauto, viella

Maria Cleary, arpa

Silvia Tecardi, viella

Recorded: 4-7 May 2005

at the Pieve SS. Tiburzio & Susanna, Badia Agnano, Arezzo, Italy

Production:

Mario Martinoli | Kees Boeke

Recording engineer: Valter Neri

Pre-editing: Kees Boeke

Digital editing: Valter Neri

Liner notes: Laurens Lütteken, Kees Boeke

Design and lay-out: Artwize Amsterdam, Charlottte Boersma

cover illustration:

The Church Militant and Triumphant (detail)

Andrea da Firenze (Andrea Bonaiuti)

1365-68 Fresco

Cappella Spagnuolo, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Ⓟ Olive Music 2006

© Kees Boeke & Olive Music 2006

Treasury of a musical epoch:

THE SOUARCIALUPI CODEX

and the music of the Italian Trecento

The

music of the 14th century excels in a number of particularities.

Although the motet had not lost its preeminence as the most important

vehicle for polyphonic music, it had to allow alongside, for the first

time in musical history, a highly perfected system of secular polyphony.

Also the artful setting of the Mass became more and more the focal

point of composers. And for the first time a clear regional

differentiation came into being, that found its very characteristic and

in any case unmistakable expression in its respective Italian and French

spheres of influence. The backdrop however for these consequential

changes, was formed by a change in the notational system that marked the

end of the 13th century. If before it had only been possible to

organize time by means of rhythmical modules of groups of notes, now, at

least in principle, the rhythmical value of each single note could be

determined. Thus the graphic symbol of the single note had become

significant in two ways: with regard to pitch by its position on a

system of lines, and with regard to time value by its graphical shape.

The new "musica mensurabilis", "measured music", made it now possible to

individualize the rhythmical form of each single piece.

The

invention of this new notation is closely linked to a generally changing

relationship to time itself which around 1300 instead of a

metaphysical, had become a physical phenomenon. This manifested itself

for example at the end of the 13th century in the invention of the wheel

clock with weight and escapement which made it possible to measure time

independently from external resources like water or light. It also

meant the end of the monastic monopoly on time. Time became the domain

of the economically flourishing cities that needed a precise and

abstract coordination of temporal spaces, for example in matters of

commerce. "Musica rnensurabilis", which enabled a completely different

control over time organisation, is closely related to this change,

however in two very separate ways. According to the scholastic doctrine,

and under the influence of the Paris University, the new notation was

developed strictly according to the rules of deduction (developing the

smaller value out of the bigger). In Italy, however, under the influence

of the more empirically oriented University of Padua, things were kept

more practical: here the procedure was inductive, i.e. one took the

smallest value, the result, as starting point and therefore had a much

more immediate access to the possibilities of this new notational

system.

This discrepancy had serious consequences for Italian

music, which already used another graphical system than the French, with

6 lines rather than 5. Apart from a pronounced reluctance towards the

motet, there existed in Italy a new style of musical expression that had

to do with the long-standing tradition of writing in two parts. The

music is not only oriented much more strongly towards sonorities, but at

the same time it pays particular attention to the musical translation

of the text, in a hitherto unknown and unusual form. This characteristic

points in any case to the fact that Italian music, differing from its

French counterpart, had its own social environment: it was a structural

part of the highly differentiated city culture of the northern and

central Italian signorie, and as such was an immediate ingredient of their local representation and self-manifestation.

A

central position between these city-states was held by Florence, the

town of Dante and Petrarca whose tuscan dialect would eventually become

Italy's national language. A special, highly sophisticated musical

culture grew in the intellectual climate in this Florence of the 14th

century; its protagonists belonged almost exclusively to clerical

circles and formed a rich network for generations. Florence in the 14th

century was a musical centre of the first order, in a period of

incessant political unrest (Dante died in 1321 in exile, as did Petrarca

50 years later), of poverty and plague (Boccaccio's Decameron being a

result), and of wars and conflicts (for example with the Visconti in

Milan). In other words, a city in an extremely unstable situation from

which eventually the power of the Medici would emerge. Notwithstanding,

or even thanks to these circumstances, public life in Florence was

colourful and brilliant, and music played its special role in this.

Although we are poorly informed about instrumental music, and mostly

through indirect sources, vocal music is richly documented. The

structural pillars were the two poetical/musical forms of the madrigal (which has nothing to do with its 16th century counterpart) and the ballata, refrain forms in which the music in a certain way echoes the structure of the text. Both madrigal and ballata could be three-part, but until the end of the century, two-part writing was preferred. On the other hand, there was the caccia, defined musically by its two canonic upper voices against an independent tenor. The caccia was the typical playground for musical artifice, like in Vincenzo da Rimini's in forma quasi.

When

we look at the opulent Florentine musical culture of the trecento, one

aspect is particularly striking: there are many direct documents,

accounts, messages, poetry—but not the music itself. Our knowledge of

the compositions is based on a manuscript that was written much later

and from which certainly nobody ever performed. A manuscript at whose

compilation only one of the composers represented on this CD, Andrea da

Firenze, could have been present; a music manuscript, however, that

belongs to the most lavish and precious that were ever produced. Today

this codex lies in the Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana in Florence and

bears the name Squarcialupi-Codex, after its possessor in the 15th

century, organist of the Florentine cathedral, Antonio Squarcialupi

(1416-1480). When and from whom he got the manuscript is unknown, and he

was certainly not involved in its compilation.

The uniqueness of

this copious manuscript lies not only in its overall lavish

presentation, its precious miniatures and its generous use of gilding.

More than anything, it possesses peculiarities that are not to be found

in any other musical manuscript of the 14th and 15th centuries, and that

shed a spectacular light on Florentine musical culture. It was most

likely manufactured between 1410 and 1415 in the monastery of S. Maria

degli Angeli, a convent that was founded around 1300 and for which

Filippo Brunelleschi had started a new church around this same time.

The

vast Codex only contains secular works (227 ballate, 115 madrigals, 12

cacce) by 14 composers that all worked permanently or at least

intermittently in Florence. It is strictly arranged according to

composer, and chronologically: the oldest, Giovanni da Cascia at the

beginning, the youngest, Andrea de Florentia at the end. The last

section of the manuscript is dedicated to Jovannes Horganista de

Florentia, but contains no entries.

This arrangement according to

composer is unique, and emphasizes a particularity of Florentine

musical culture: the perception of the single work as expression of the

individuality of its composer. This corresponds to the fact that all

sections are preceded by precious miniature portraits of each musician:

images that certainly do not resemble the actual people, but have the

goal of demonstratively illustrating the singularity and uniqueness of

each individual. Indeed, not only the individual composers, but each

single work in the Squarcialupi-Codex is proof of and plays its part in

this new cultivation of musical individuality. If one listens for

example to the clear separation of vocal and instrumental sections, and

the refined treatment of rhythm in Giovanni da Cascia's homage to music (O tu cara sciença),

the oldest piece present on this recording, the difference from the

compositions of Andreas de Florentia becomes manifest, and not only

because the latter are in 3 voices. The sonorities of the stormy Deh, che faro form as much of a contrast with the former as they do with his own elegiac Dido-ballata Non più doglie.

Each

composer is present in the manuscript as his own, unique personality.

Looking at the works themselves, we can recognize these tendencies

towards individualisation in every detail. Thus, the Signoria of

Florence in the 1451, century was permeated by a musical culture that

was as self-willed as it was ambitious. Its prerequisites lied as much

in the notational possibilities of a new system of organizing musical

time, as in the effectiveness of music in the realm of city

representation.The composing clerics of Florence decidedly changed the

history of music, much like Dante and Petrarca changed the history of

literature. The belated mirror of this is the Squarcialupi-Codex,

likewise produced in a monastery: a representative document, a musical

treasury of a whole epoch.

BIOGRAPHIES

Andreas de Florentia,

probably a native of Pistoia, is one of the few composers in the 14th

century, whose life is relatively well documented. His life is closely

connected to the spiritual centre of Florence, around the church of the

Santissima Annunziata. It was founded by the order of the Servi di Maria

of Monte Senario that established itself in Florence around 1250 and

soon became an important place of pilgrimage because of the miracle of

the fresco (the completion of an Annunciation, begun by Bartolomeo, by

an angel). Andrea, born perhaps around the middle of the century,

entered the monastery that had for some time pursued ambitious new

building projects, in 1375. Trained as an organist (hence his surnames

Frater Andreas Horganista or Andrea degli Organi) he was, together with

Francesco Landini, responsible for the construction of a new organ in

the cloister church, and a little later, in 1387, also in the cathedral.

In his order he had a meteoric career, from master of the novices

(1379) to prior (first time in 1380) and then to head of his order

(1407-1410). The extant oeuvre of Andrea is voluminous,

comprising 18 works for two, and 12 for three voices; they are

exclusively ballate that, except for one composition, appear only in the

Squarcialupi codex. He died in Florence in 1415.

Bartolino da Padova.

When Bartolino was born is unclear, but it was probably in Padua. There

he entered the order of the Carmelites, and possibly he was even prior

in his monastery. Apparently he stood in close relationship to the

Carrara family until their downfall after the conquest of Padua by the

Venetians in 1405. It seems that he lived in Florence during the

penultimate decade of the 14th century, maybe in the company of the

exiled Francesco Novella. (portrait) Several of his extant works are

connected with concrete political events in Padua. Although Bartolino's

padovano background is unquestionable, he was clearly also an extremely

well-known composer in Florence. Of him 38 works are attributable (27

Ballate and 11 Madrigals), and 37 are preserved in the Squarcialupi

Codex, partially as unica. Some of the compositions exist in versions a 2

and a 3, whereby it is unclear which is the older version, and if the

third voice is actually in all cases by the hand of Bartolino himself.

Gherardellus de Florentia

probably spent all his life in Florence. The first traces of him are

found in 1343 as a cleric by the name of "Nicholo" at the church of

Santa Reparata, i.e. the cathedral that had already become a major

construction site since the inception of the building of the new

cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore. He obtained a position there as a

chaplain in 1345, which held until 1351. After that, and maybe also

because the stagnating works on the new cathedral had been resumed, he

changed over to the order of Vallombrosa. There might be a connection

between this and his change of name, since in one document he is named

‘Ser Nicholo vochato Ser Gherardello’. Until 1362 he is traceable in

Santa Trinità, at the church of the Vallombrosians, after which we lose

track of him. In a

sonnet from the 1360's his death is lamented by

the poet Simone Peruzzi. Among the works of Gherardello are found sacred

compositions, solo ballate, 10 two-part madrigals and a three-part

caccia.

Giovanni da Cascia's biography is not supported by

any certain documents. He seems to originate from Cascia (near

Florence) as his name suffix indicates. Possibly he is identical with an

organist by the name of Giovanni (in the Squarcialupi Codex he is

depicted with an organetto), who worked around 1360 in the imposing

church of Santa Trinità, the church of the Vallombrosians which had been

consecrated in 1327. However, in the 14th century the name "Giovanni"

was more or less used at random, and so we can not be all too certain.

At any rate, it seems that Giovanni da Cascia was no cleric, and on the

basis of his works we may assume that his main activity belongs to the

first half of the century. 19 Madrigals have been preserved (no

ballate), and O tu cara sciença mie musica must have been one of the most popular songs of its time, as it survives in no less than five manuscripts.

Laurentius de Florentia,

also known as Ser Laurentius Masii or Masini, belongs to the most

influential circle of Florentine musicians around the middle of the 14th

century. He is first mentioned in his native city Florence in 1348 as a

canon at the Basilica di San Lorenzo, at that point in time the

building still dating from the 11th century, which was, through

encouragement of the Medici, replaced in the 15th century by the famous

new church. Laurentius was linked to San Lorenzo all his life, the

church where Francesco Landini also worked from 1365 onwards. Although

comparatively few works have been preserved by him, he was still

considered a celebrity in the 15th century. There remain a Sanctus, a

caccia, ten two- and three-part madrigals as well as five ballate. He

set texts by Boccaccio and Dante to music.

Nicolaus de Perugia,

as one of the few composers present in the Squarcialupi Codex, does not

come from Florence or its surroundings, but from Perugia. He must have

spent some time in Florence, though, since in 1362 he visited the same

Santa Trinità monastery of the Vallombrosiani in which Gherardellus had

been active up to that year. As in the works of Andrea da Firenze, we

find references to the Visconti from Milan, who were at war with

Florence at the end of the 14th century. Notwithstanding the fact that,

in certain aspects, Nicolaus apparently was an outsider in the group of

Florentine composers (also visible in certain stylistic peculiarities),

his works are unusually well documented and almost exclusively in

Florentine sources: more than 20 two-part ballate, almost 20 two-and

three-part madrigals as well as three cacce.

Vincenzo da Rimini

seems to originate from the area of Rimini or Imola, if we can trust

his description as "Abbas de Arimino" or respectively "l'abate Vincençio

da Imola". Nothing certain is known about his life in, or connection

with Florence. It is equally unclear whether he as Benedictine had

anything to do with Santa Trinità. His preserved oeuvre is very small

(four madrigals and two cacce) but shows exceptional originality in both

the cacce.

Laurenz Lütteken

Translation: Kees Boeke, Robert Claire

THE COMPOSITIONS

Codex Squarcialupi (ca.1340-ca1400)

(Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, MS. Palatino 87)

GIOVANNI DA CASCIA

— O tu, cara sciença mie musica (madrigale) a2

This

madrigal in praise of the art, or better, science of music lacks, as is

unfortunately often the case, the second stanza. In order to preserve

the musical form in its integrity, we have provided an instrumental

rendering of the missing verse. Noteworthy is the emphasis on "dolce

melodia" and "vaghi canti", epithets later also frequently used by other

trecento composers and often associated with Landini. The top

part is clearly written in an already highly developed diminution style:

two different readings, from Sq and Pan. have been adopted here, as

well as a hypothetical "simple" version of the Cantus in the harp.

GHERARDELLO DA FIRENZE

— Una colomba (madrigale) a2

Typical

allegorical madrigal with a second ritornello (AABB). Text setting is

perfectly syllabic, suggesting that the remaining material is to be

performed instrumentally. The opening phrase ("Una colomba") seems to

have been picked up by Ciconia for his "Una Panthera". Instrumental

intermezzi and vocal melismas are astonishingly descriptive of the text.

The enigmatic, undecipherable "sguardo d'amore" of the beloved (the

colomba) signifies suffering or delight. The lover remains caught

between two worlds, or interpretations.

There is a dreamlike quality to the scene.

LORENZO MASINI

— Dolgo mi a voi (madrigale) a3

This

is the second madrigal devoted to music, this time in a negative, or

critical vein. It is a complaint against dilettantism in music

(scientia!) and derides and imaginatively illustrates how amateurs ruin

our notes. The musical illustration comprises a surprising variety of

effects: offensive or overly sweet harmony, inappropriate trumpet

signals, the ridiculous ut re mi fa sol to describe the guidonian hand,

and the "perfect" ending to conclude the argument. On the whole, this

madrigal is actually written in the form of a derailing canon

or"caccia". Again we must regret the missing second stanza.

— I credo ch'i dormia (madrigale)

Another

dream, a favourite topic with the early madrigalists. Since the text is

incomplete, it is hard to get a clear picture of the event that is put

into music here. The mere quantity of musical material almost suggests a

type of mini-opera! The lover sees the goddess of Love at the moment of

falling in love.., then what happens? ...but he remains pensively in

the dream, in love with his Lady. There are very few lyrics, but the

music suggests a stormy event in the (missing) second stanza.

VINCENZO D'ARIMINO

— In forma quasi (caccia) a3

This

is an authentic caccia that combines depicting the dream state between

sleeping and waking with an idea very similar to the three centuries

younger "Cries of London". There is a storm, a harbour scene with

fishmongers shouting. The protagonist wakes up to the noise and returns

to sleep, as does the music. There is a particularly unreal cadence in F

major at the end of this d Dorian composition.

NICCOLO DA PERUGIA

— O sommo specchio (madrigale) a3 inst

A

very unusual, and perhaps unique, through-composed madrigal: the verse

lines flow into each other, merely separated by vague cadential moments;

the second stanza continues seamlessly from the first with entirely

different music. The counterpoint and ficta games are highly

speculative; a correct text underlay is either impossible or perfectly

arbitrary.

BARTOLINO DA PADOVA

— Non correr troppo (ballata) a3

One of several madrigals (cf. Chi tempo ha)

of a moralistic nature, with an admonition against haste. The music

seems ironical and vividly depicts the flow of time, the haste and the

"freno" in rhythm, melody and harmony. In modern Italian the saying

goes: "Chi va piano va lontano" . The counterpoint and harmonic idiom

seem to follow the road taken by O sommo specchio.

— Recorditi di me (ballata) a3 |

contratenor from Codex Mancini, Lucca

We added the contratenor that survives in the Codex Mancini

although the piece is incomplete (and completed here). A very delicate

love song where the lover says "I am perfect, but you rejected me

without giving any reason..." The phrases are separated by pauses (of

perplexity?) as happens also in some ballate by Andrea and Landini.

— Inperiale sedendo (madrigale) a3 |

contratenor from Codex Mancini, Lucca

Emblematic/heraldic

madrigal in honour of Francesco Novello da Carrara, who was the

governor of Padova at the time. It was sufficient to mention the

"Saracino" to indicate the Carrara family. It was probably written in

1401 to celebrate the investiture of Francesco as imperial general by

the then-newly elected Emperor Ruprecht of the Rhine Palatinate (Robert

of Bavaria). Ciconia's Per quella strada and Con Lagrime bagnandome were written also for the Carrara family. It is no surprise, then, that the musical language and construction of Inperiale show remarkable similarities with Ciconia's famous Panthera

(opening, ending and the fanfare-like intermezzo). There Remains the

tintillating question of who was first... We have integrated the

Contratenor from the Mancini Codex, which, with its manneristic

syncopations is very typical of Bartolino. We have interpreted the

"quaternaria" at the end of the piece as an "octonaria" in so-called

"longa" notation.

— La doulce çere inst (CODEX FAENZA)

The

madrigal La doulce çere most likely refers to a specific person in its

heraldic symbols, but lacks a reference to any single datable event; it

was presumably written to honour a descendant of the Papafava family in

the years preceding the suppression of their arms by Francesco Novello,

whose signoria spanned the period 1390-1405. This is the diminution as found in the famous Codex Faenza.

ANDREA DA FIRENZE

— Planto non partirà (ballata) a3

— Sotto candido vel (ballata) a3

— Donna, bench'i' mi parta (ballata) a3

— Presuntion da ignoranza (ballata) a3

— Perché veder non posso (ballata) a3 inst

— E più begli occhi (ballata) a3

— Deh, che farò? (ballata) a3

— Non più dogli ebbe Dido (ballata) a3

Andrea's

compositions are unique in their avantgardistic compositional

technique, with recognizable elements from Bartolino, Landini and

Ciconia, and very unusual in their thoroughly through-composed manner.

This might be music that was understood only by a small circle of

connoisseurs, but did not "export". Certainly his stylistic

extrapolations of the truly Italian trecento tradition are very

different from the choices made for example by his equally eccentric

colleague Matteo da Perugia in Milan, who tried to exalt the French Ars Subtilior

in his own way; both were equally "unsuccessful" in the end and the

course of history preferred the much more harmonic and streamlined

solutions found by Ciconia. Six out of eight ballatas presented here are

love songs with intense and often bitter and moralistic overtones. Presuntion makes a poignant moralistic statement against arrogance, the fruit of ignorance. The moving final song "Non più dogli ebbe Dido" can be read both as an homage to (polyphonic) music, and as an eulogy of Andrea's favourite instrument, the organ.

© Kees Boeke