medieval.org

Olive Music, Et'Cetera KTC 1900

2008

medieval.org

Olive Music, Et'Cetera KTC 1900

2008

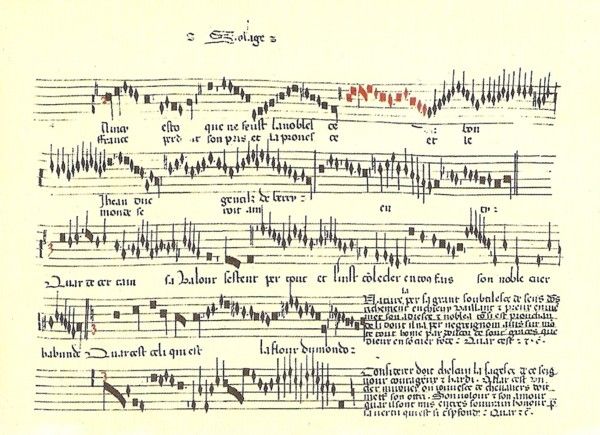

SOLAGE

1. S'aincy estoit que ne feust la noblesce [12:34]

fol. 36 — ballade

2. Un crible plein d'eaue de vray confort ~ A Dieu vos comant, baudor [3:14]

fol. 13v — virelai

Philipoctus da CASERTA ?

3. Médée fu en amer veritable [10:08]

fol. 24v — ballade

Antonello da CASERTA ?

4. Je ne puis avoir plaisir [5:31]

fol. 24 — virelai

GALIOT ?

5. Se vos ne volés fayre outrage [2:34]

fol.40\2 — rondeau

Matteo da PERUGIA ?

6. De quanqu'on peut belle et bonne estrener [5:58]

fol. 28 — ballade

Franciscus ANDRIEU

7. De Narcissus, home tres ourgilleus [9:12]

fol. 19v — ballade — (Magister Franciscus)

Jacob de SENLECHES

8. Je me merveil aucune fois comment ~ J'ay pluseurs fois pour mon esbatement [13:58]

fol. 44v — ballade — (Jacob Senleches)

TETRAKTYS

Kees Boeke

Jill Feldman, chant

Carlos Mena, chant

Marta Graziolino, arpe

Silvia Tecardi, vielle

Kees Boeke, vielle, fluste

Vielles:

Robert Foster, UK 2003

Maurizio Marcelli, Rieti 1997

Fabio Galgani, Massa Marittima 1996

Flustes:

Luca de Paolis, l'Aquila, Italy

Diapason: 523 Hz

Temperament: Pythagorean

Recorded: 12-15 February 2007

at the Pieve di San Pietro a Presciano (Arezzo)

Production:

Jeannette Koekkoek | Kees Boeke

Recording engineer: Valter Neri

Pre-editing: Kees Boeke

Digital editing: Valter Neri

Liner notes: Laurens Lütteken

Design and lay-out: Artwize Amsterdam

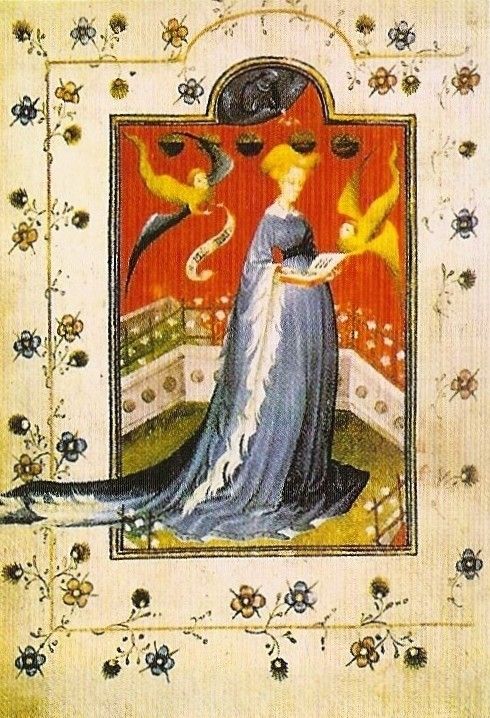

cover illustration:

Prayer-book of Maria van Gelderen, (before 1415), vellum, 18,1 x 13,4 cm

Staatsbibliothek Preussischer, Kulturbesitz, Berlin

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry - The Adoration of the Magi

(detail folio 52r), Musée Condée, Chantilly

Ⓟ © Olive Music 2008

The compositions of the Chantilly Codex and the music

around 1400: at the limit of what is possible

Among

the great innovations in music of the 14th c. belongs the "musica

mensurabilis", "measurable music" which was invented "out of the blue"

at the end of the 13th c. and was definitively transformed during the

second decade of the 14th. The foundation of this "musica

mensurabilis", which was a reaction against the "unmeasured" Gregorian

chant, was a new graphical system, a new kind of musical notation which

essentially measured long and short values.

The crucial novelty

therefore was the possibility to assign not only a relatively exact

pitch (by its position on the five or six lines) to a single graphical

sign, i.e. a note, but also a precise duration (by its shape). Thus the

note could be read in two senses. In this way, polyphonic compositional

processes could be individually structured for the first time in

musical history and were no longer dependent on predetermined patterns.

The composers immediately jumped on this possibility, especially in the

realm of the motet, and with such fervour that they had already shortly

after 1300 more or less exhausted the limits of the system. For this

reason the system was once again fundamentally revised after 1310, in a

certain way it was rationalized and stabilized. The main problem here

consisted in the division of the central note value, the Brevis, which

could in the period shortly after 1300 be divided in up to 7 or even 9

equal parts. The subsequent rationalization provided, on the other

hand, only for a (perfect) division in 3 and an (imperfect) division in

2, and this starting from the Brevis down all the levels of hierarchy.

These newly created possibilities were immediately applied, not only to

the genre of the motet, but also to the new and upcoming secular song

(with Ballade, Rondeau and Virelay). The use of plainsong in this new

style of polyphonic motet was nevertheless so controversial that pope

John XXII intervened in this development in the mid 1320's and tried to

veto this form of polyphony.

However, the created system, which

was called "novus" by its inventors and thereby gave its name to the

whole epoch ("Ars Nova") was, albeit with regional differences, spread

all over medieval Europe and remarkably consistent, even though the

transmission through manuscripts in the entire 14th century, and

especially in its second half, is not particularly assertive. The

number of surviving manuscripts is in fact quite scanty, even if we

have proof of the existence at the time of a non-negligible quantity of

other mss. from library catalogues for example. Nevertheless:, the

source situation is precarious, which makes any more generalized

assertion difficult. At least, however, we can recognize a certain

tendency: towards 1400, in fact, composers once again demonstrated a

propensity to exhaust the possibilities of the notational system,

within the limits irreversibly imposed on it. Its focus consisted in a

new fascination for the most complex rhythmical articulation in

polyphonic musical composition. As opposed to 1300, this was not as it

were an

unorganized and unregulated creative explosion, but

precisely the contrary: in the motets as well as in the secular works,

we see the controlled refinement of an already intensively tested

potential related to a precise stylistic imagination that was

intimately linked to the texts set to music. What was, time and again,

described by contemporaries as the "subtilitas" of these compositions,

led to the christening of this period with the not quite unproblematic

term "Ars subtilior".

Again, few manuscripts document this

phase. The most significant among them is the codex which today lies in

the Muséé Condé in Chantilly. It arrived there only in 1861, however,

as part of the famous art collections of the Duke Henri d'Orléans, Duc

d'Aumale (1822-1897). The Duke inherited the Renaissance castle

Chantilly from the Condé family in 1830, in which he accommodated his

collections and which he ultimately donated to the "Institut de

France". To his most precious acquisitions belong the famous Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, originated in the 15th century.

The

Duke had a sumptuous new binding made for the music manuscript in 1880

and it is possible that through that important characteristics went

lost. He bought it in Florence, where, according to a remark on one of

the first pages, it had been since 1461. Apart from the apparently

Tuscan copyist, also the 6-line system, typical for Italian trecento

repertoire, which is used throughout the manuscript points at an origin

in Italy, even maybe in Florence.The contents - 13 Latin motets in

addition to 97 almost exclusively French songs - do not contradict

these origins: French music was still widely spread in northern Italy,

even as far as Rome or Naples.

The precious parchment manuscript

supposedly was written around 1400 with the exception of the two pieces

that became famous for their "graphical" notation (in the form of a

heart and a circle, respectively) which were completed a little later.

Whether the codex was somehow connected to an Italian court (such as

Milan or Pavia) or not, must remain open, though it is not unlikely.The

assembled repertoire excels specifically in the way that notational

complexities are pushed to the extreme, a fact that for many decades

left schollars in a state of perplexity. They could not agree on the

sense of this impossible technique or even considered it only a mental

exercise. Now, after some decades of experience in the performance

practice of music of the 14th and early 15th century, the opinions have

seriously changed. Not only have the greatest notational and rhythmical

difficulties become playable and singable, but even more importantly it

has become slowly clear that the "subtlety" in this music consists in

its refined relationship to the text/lyrics/poetry. In other words, we

are dealing with text-expression, albeit in a different form than we

know it from the "Klavierlied" in the 19th century.

One of the

great events of the 14th century was the fact that it was now possible

to compose secular song polyphonically. A new, fresh musical genre saw

the light. It drew its formal criteria from the fixed structures of

lyrical poetry, known as "formes fixes".Among these, the emphasis was

laid on the Ballade, whereas the Rondeau and Virelay played at that

point in time a relatively minor role. All these forms are Refrain

forms, but in the Ballade this is most clear and manifest: in principle

there are two identical musical verses (characterized by an "ouvert"

and "clos" ending) and a concluding part of which the ending in its

turn is mostly identical with the "clos" (A1A2BC). Usually there are

three rhymed strophes, sometimes more, sometimes less. Thematically the

Ballade can sweep over many subjects and is - unlike the Rondeau and

Virelay - not exclusively concerned with love poetry. The works on this

recording belong to the most beautifuland complex Ballades of the

repertoire. Some of these feature themes from antiquity: in Andrieu's De Narcissus

the story of Narcissus, in love with his own mirrored image, is told

allegorically in an unusual musical setting, and characterized by

sweeping vocal melismas. The many stylistic similarities with another

Chantilly composition by F. Andrieu, "Armes, amours", a lament

on the death of Machaut, lead us to believe that Magister Franciscus is

identical with the composer Franciscus Andrieu.

In Médée fu

on the other hand, the couple of lovers is compared to famous

mythological couples like Jason and Medea, Helena and Paris. Poems

which quote ancient heroes and lovers to compare them with contemporary

people were extremely fashionable at the time. In this Ballade the

comparison is used against the lady: She is less faithful even than

Medea, Helen and Bryseida, none of whom is particularly famous for her

virtue.The affective confusion is expressed through a tense,

ultra-sensitive setting, in which no notational complication is left

out. Time and again we find peculiar harmonic turns that highlight

certain text lines, if not single words. After all we observe clear

traces of Italian music here. The closing line (refrain) of the poem

"Ma dame n'a pas ainsy fait a-my" can be read two ways: "This

way my lady did not make a friend" and "This is not how my lady behaved

towards me", a typical pun on the word amy. Chantilly contains

six compositions by Philipot/Philipoctus, and stylistic similarities as

well as the serious quality of the writing might suggest him as the

author of this magnicent Ballade.

The Italian influence is also visible in De quan qu'on peut,

a work that in its eccentricity could easily have been written by

Matteo da Perugia, or at least have been influenced by his style. The

flavour of the musical refrain at the end of the A and B sections and

the persistent polyrhythmical setup of this piece very strongly remind

us of this extraordinary subtilior composer. There is no other

ascribed composition by him in the Chantilly Ms., although several

Chantilly pieces were copied in the Modena Ms., the main source for

Matteo's works. The incipit of the text - De quan qu'on peut - Of all one could give

- becomes as it were its own compositional program, by the fact that

indeed it unfolds a kind of rhythmical compendium, with only a certain

calming down at the beginning of the second part. Both upper voices,

although clearly differing in tessitura, are melodically so similar

that they create the type of setting that a little later was favoured

by Johannens Ciconia, although completely without rhythmical

complications. One can hear this particularly well in the instrumental

version of the piece recorded here. Through these intensifications the

polyphonic song ultimately strove to equal the ambitions of the motet.

That the latter in the background was still considered the "touchstone

of perfection" is shown in several works. An outstanding example is the

Ballade Je me merveil by Senleches in which, just like in a

motet, two text are simultaniously sung in the upper voices. It is

striking, however, that the composer ignores the usual hierarchy

between motetus and triplum and treats all three voices equally, or

both higher ones as a kind of duo, the lower one as "harmony carrier"

(though not rhythmically separated). The Ballade fulminates against

musical dilettantism, a favourite subject among 14th century composers,

Italian or French. To illustrate the subject, the notation and

"subtilitas" of this composition are stretched to the limit,

culminating in the canonic refrain which is however not notated as a

canon. Senleches writes down the same identical music with two

completely different notational systems.

Similarly, also the

only Virelay on this recording, Un crible plein d'eaue - A Dieu vos

comant, owes much to the motet. This very clever composition uses

apparently a simple folk song as a kind of isorhythmic tenor, with a

slightly histerical cantus, that fulminates against the traps of

marriage. The particularly angular contratenor in syncopated binary

rhythms exemplifies the terrible conflicts of which the text speaks.

The little Rondeau-like Se vos ne voles

lacks its full text, although the musical composition is apparently

complete. It appears on the same page that contains another full-sized

Rondeau by Galiot, hence the ascription.

Solage's Ballade S'aincy estoit

on the other hand shows itself a grandiose eulogy to Jean, Duc de

Berry, a possible commissioner of the Chantilly Ms. It was probably

composed in 1389. 15 years later the same Duke commissioned another

famous manuscript, the Très riches heures... Solage employs

extreme harmonical and rhythmical means to underline his subject

matter, which at times create serious difficulties in judging his

ultimate intentions. The proposed text underlay produces highly

illustrative instrumental interludes and comments.

Biographies

The

transmission of composers' names is still an exception in the 14th

century (and even during the following century). As a rule pieces are

written down anonymously in the mss. However, also from this point of

view, the Chantilly Codex occupies a special place: of the 110

preserved compositions, 32 are anonymous, which equals about 30%.The

remaining can be ascribed to 33 different authors, although not all of

them are mentioned in the codex. They are identifiable through parallel

sources, so called concordances. Anyway, the number of compositions

with a certified author is considerable and proves the status assigned

to these works of art. On this recording we find, apart from one

anonymous work, songs by the following composers:

F[ranciscus] Andrieu

is mentioned (with abbreviated name) as the composer of a

double-texted, four-part Ballade, written in 1377 on the occasion of

the death of Guillaume de Machault. The poem was written by his

student, Eustache Deschamps, famous French poet of the second half of

the 14th century. There are two further works (three-part Ballades) in

the Chantilly Codex, however not headed with F. Andrieu but with

"Magister Franciscus". Scholars, however, assume that this is the same

person. So far, any further biographical details are unknown.

Galiot

i s anothern ame that we only meet in the Chantilly Codex, as the

author of four works. Unfortunately the copyist seems to have made an

ascription error in two of them, so that in the end only two are really

irreproachable. Also his identity is a mystery, because it is not even

certain that this is a real name (Gian Galeazzo Visconti has been

proposed as a candidate). One of the works ascribed to him (without

however mentioning his name) is considered very influential for the

musical culture in Paris before 1400 in a Hebrew treatise of the early

15th century.

Matteo da Perugia belongs to the most eccentric composers of the period round 1400, at any rate as far as his oeuvre

is concerned. On the other hand, we hardly know anything about his

life. His name suggests his origins from Perugia, from where he

apparently went to Milan for whatever reasons. There is proof that in

1402 he was Maestro di Capella at the Cathedral there, at that point a

major construction site. Matteo was a cleric, maybe even a Franciscan.

He arrived in Milan with the Franciscan Filargo di Candia, who had been

elected Archbishop in 1402. It seems that Filargo, in the meantime

promoted to Cardinal, took his Maestro di Capella with him to the

council of Pisa in 1408 where there was an attempt at mediation between

French and Roman interests. This culminated in Filargo being chosen

Antipope Alexander V in 1409. Matteo may have served as a Maestro di

Capella to the pope after that. Unexpectedly, however, his patron died

the next year and was succeeded by John XXIII. It seems that Matteo

left Pisa at that point and we lose track of him until 1414, when we

find him back at the cathedral in Milan. Once again he is traceable

there in 1418 after which he disappears from the archives indefinitely.

There is no proof that Matteo was still alive in 1426, as has recently

been suggested. His compositions are exceptionally artful and

experimental. Four Ballades can certainly be ascribed to him.

Also Philipoctus

can not be traced in the archives as a person. His authenticated

compositions suggest links to the papal court in Avignon as well as the

court of the Visconti in Milan or Pavia. Nothing is known about the

functions he could have exercised there. The existence of a Credo by

his hand however suggests that he worked in a court chapel or

cathedral, which means that he must have been a cleric. We find his

name four times in Chantilly (as "Phot" and "de Caserta") pointing to

his southern Italian origins. Two more works can be certainly

attributed to him by means of existing concordances. Until now Médée fu has not been discussed as a possible composition by Philipoctus, but similarities to his other works, especially Par les bons Gedeon e Samson, make this attribution plausible.

It is possible that Jacob de Senleches

was born in the small village Senleches in the diocese of Cambrai. In

1383 we find a certain "Jacquemin de Sanleches" at the court of

Navarra, but in the service of Pedro de Luna, the later Pope Benedict

XIII. Since he is emphatically mentioned as a "juglar de harpa", the

identification with the composer is not without problem: we can assume

that a learned composer, who was capable of reading and writing, led

the existence of a cleric. A harpist, on the other hand, belonged

unequivocally to the class of instrumentalists, or minstrels. There is

some indication that Senleches was active in Lombardy and around the

circles of the Visconti court. He would thus be a further Chantilly

composer with connections to Milan. Only four works are known by him

beside Je me merveil and the Virelay La harpe de melodie, which was much admired by his contemporaries.

Whether Solage is indeed a

name or only a kind of epithet or anagram must remain conjectural. This

is no exception in Chantilly (e.g. Trebor=Robert) and "Solage" could be

a similar word game (a combination of "sol"and "age"?). Nevertheless

there are twelve identifiable compositions under this name that can not

be connected to any known person. The text of some of his compositions

could indicate that he was active in France, but even that has to

remain speculation.

Laurenz Lütteken

translation Kees Boeke, Robert Claire