medieval.org

Naxos 8.553131

1994

medieval.org

Naxos 8.553131

1994

1. [7:26]

Chominciamento di gioia [4:14] —

Saltarello #4 [3:12]

2. [6:19]

Lamento di Tristano [4:30] —

La Rotta [1:49]

3. Bellicha [2:14]

4. Tre Fontane [4:58]

5. Parlamento [4:51]

6. Principio di Virtu [4:30]

7. Saltarello #1 [2:36]

8. Trotto [2:29]

9. Saltarello #2 [1:50]

10. Isabella [8:48]

11. Ghaetta [7:25]

12. Saltarello #3 [0:58]

13. In Pro [4:31]

14. [2:46]

La Manfredina [2:18] —

La Rotta [0:28]

Ensemble Unicorn

Michael Posch, recorders

Marco Ambrosini, keyed fiddle, fiddle, mandorla, kuhhorn, shawm, ocarina

Riccardo Delfino, hurdy-gurdy, harp, bagpipe, dulcimer

Thomas Wimmer, ud, fiddle, saz, vihuela d'arco

Wolfgang Reithofer, percussion

All arrangements by Ensemble Unicorn.

Recorded at Tonstudio W. A. R., Vienna, in January 1994.

Engineers: Elisabeth and Wolfgang Reithofer

Music Notes: Riccardo Delfino

(Eng. trans. by Uta Henning)

All texts and photographs by Michael Posch and Wolfgang Reithofer.

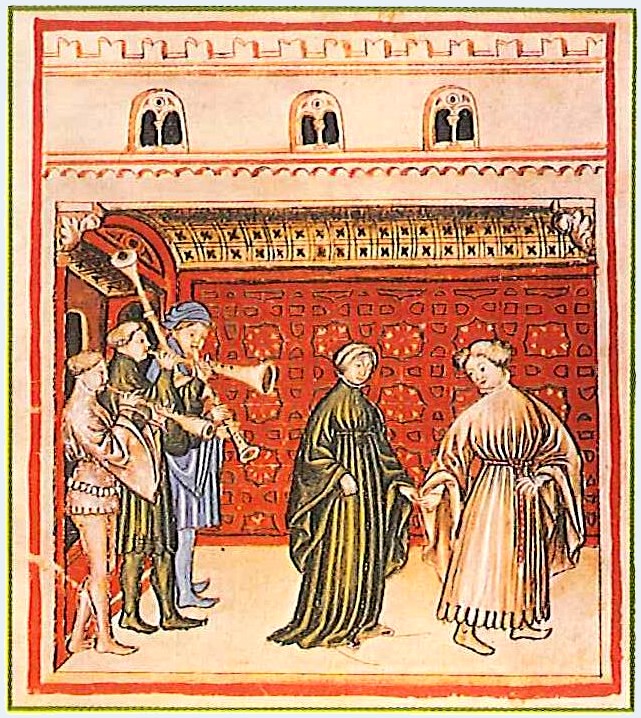

Cover: Sonare et balare

(Austrian National Library)

Ⓟ © 1994 HNH International Ltd.

Chominciamento di gioia

Virtuose Tanzmusik zur Zeit von Boccaccios Decamerone

Als

im Jahre 1348 die Pest ihren Einzug in Europa hielt, fanden in der

Folge circa 25 Millionen Menschen den Tod. Diese Zeit der Schrecken und

Wirrnisse führte auch zum Tode eines veralteten Weltbildes, das von

theologischen Dogmen und kirchlicher Moral geprägt war. Gleichzeitig

keimten in den norditalienischen Städten der Frührenaissance neue

kulturelle Impulse: der Humanismus, demokratische Staatsformen und

blühender Handel. Die Schicht der Patrizier und Bürger erlangte durch

die Tuchindustrie Reichtum und Macht und wurde zum neuen Träger der

Kultur. Sie finanzierte die Gründung von Universitäten, in denen

Erkenntnisse auf kreative, empirische Weise erarbeitet wurden und die

sich mehr und mehr dem Einfluß der Kirche widersetzten. Nicht mehr Gott,

sondern der schöpferische Mensch stand im Mittelpunkt des Interesses

und wurde philosophisch, historisch und medizinisch erforscht; die

Neuzeit wurde geboren.

In Giovanni Boccaccios Novellensammlung

“Il Decamerone” (1353) wird die Geschichte von zehn jungen

florentinischen Edelfrauen und - männern erzählt, die sich für zehn Tage

vor den Schrecken der Pest auf einen Landsitz zurückziehen, um sich

singend, tanzend und Geschichten erzählend an der Kunst zu erfreuen. Ihr

Zusammenleben ist noch geprägt vom hohen Ideal der mittelalterlichen

Minne, doch bildet gleichzeitig die Darstellung der triebhaften Liebe,

gepaart mit geistreicher Geselligkeiteine neue weltfreudige und

praktische Moral heraus.

Vielfältig sind die Hinweise im Decamerone auf die Musikpraxis der Zeit.:

“...die

Königin gebot, da alle Damen, ebenso gut die jungen Männertanzen, und

ein großer Teil von ihnen auch sehr schön spielen und singen konnte, da

Instrumente gebracht würden; dann nahm, auf ihr Gebot, Dioneus eine

Laute und Fiammetta eine Fidel und fingen an einen Tanz zu spielen.

Hierauf trat die Königin mit den anderen Damen und auch den beiden

jungen Männern zu einem Ringeltanz an... Als der Tanz geendet war,

sangen sie niedliche, fröhliche Lieder.” (1. Tag, Einführung)

An anderer Stelle wird eine liebeskranke Dame mit Musik getröstet:

“Minuzzo

aber ward zu damaliger Zeit für einen sehr feinen Sänger und Spieler

gehalten ... nachdem er ihr mit liebevollen Worten zugeredet hatte,

stimmte er auf seiner Fidel eine Stampita auf eine sehr süße Weise an,

worauf er alsdann eine Canzone sang.” (10. Tag, 7. Novelle)

Einerseits

war die “Ars Musica” nicht mehr ein spekulatives Auslegen der Schriften

in klösterlichen Schreibstuben zum Beweis und zur Ehre Gottes, sondern

eine von jedermann im Alltag praktizierte Kunst. Andererseits - so wie

Boccaccio Volkssprache und Volkserzählungen auf eine künstlerische Ebene

gehoben hatte - lauschte man auf die Tänze des Volkes, die dort als

Gehörs - und Improvisationsmusik lebten, und brachte sie als

Vortragsmusik in eine künstlerische Form.

Eine der ersten

Handschriften reiner Kunst- bzw. Tanzmusik stammt aus Norditalien und

wird unter der Sigelnummer 29987 in der British Library in London

aufbewahrt. Neben mehreren Madrigalen, deren Sprache und Notationsart

die Niederschrift um das Jahr 1390 datieren lassen, finden sich am Ende

der Schrift 15 monophone Instrumentalstücke. Sie weisen alle die damals

übliche Form der Tanzmusik auf: mehrere in Anzahl und Form variierende

“parti” (voneinander unabhängige Teile mit oftmals improvisatorischem

Charakter) enden jeweils immer in demselben “aperto” (Halbschluß) bzw.

nach ihrer Wiederholung im “chiuso” (Ganzschluß). Auch die ausdrückliche

Benennung der Tanzart der ersten acht Stücke als “istanpitta”, der

folgenden vier als “saltarello” und des 13. als “trotto” deuten auf

Tanzschritte (stampfen, hüpfen, traben). Doch schon die letzten beiden

Stücke werfen bezüglich der Tanzbarkeit Fragen auf; “Lamento di

Tristano” und “La Manfredina” sind von ihrem Charakter her eher

getragene Kompositionen, auf die eine schnelle Variation, die sogenannte

“rotta”, folgt. Am deutlichsten als Tanzmusik erkennbar sind der

“trotto” und die “saltarelli”, die in ihrer Struktur einfacher und

eingängiger sind als die “istanpitte”. Letztere geben am meisten Rätsel

auf; schon durch ihre Länge heben sie sich von den anderen Kompositionen

ab. Weitläufige improvisatorische Umspielungen der Melodielinien und

oft auftretende Quint- und Quartsprünge stehen ganz in der damaligen

instrumentalen Musizierpraxis, die von der arabischen Kultur geprägt

war, und liegen gut in der Hand auf den Instrumenten der Zeit (Fidel,

Blockflöte, Harfe, Ud, Dudelsack..). Sie geben den “istanpitte”

gelegentlich einen minimalistischen Zug. Andererseits verlieren sich

manchmal die “parti” in “melodischen Höhenflügen” mit an moderne

Chromatik erinnernde Vorzeichenwechsel, mit sich verschiebenden

Rhythmen, mit Tonumfängen über zwei Oktaven, was Tanzbarkeit und

Spielbarkeit auf historischen Instrumenten schier übersteigt. Fast

erscheint es, als wären die “istanpitte” eine “experimentelle Musik” des

14. Jhdt., der Versuch, die Grenzen der neuen instrumentalen Kunstmusik

zu definieren. Erstmalig in der Musikgeschichte wurden Titel

vorangestellt, die fast programmatisch wirken.: “Bellicha” (Die

Kriegerische), “Parlamento” (Gespräch), “Ire Fontane” (Drei Quellen),

“Ghaetta” (Die Fröhliche), “In Pro” (Bitte), “Principio di virtú”

(Prinzip der Tugend), “Isabella” und “Chominciamento di gioia” (Anbeginn

der Freude).

Waren diese Kompositionen ein unerhörter Griff in die Zukunft, ein Vorläufer der Maxime “l'art pour l'art”?

In

dieser Einspielung liegen sämtliche instrumentalen Titel der

Handschrift 29987 vor. Wir haben uns bei der Interpretation am Stil der

Zeit orientiert und uns des entsprechenden Instrumentariums bedient,

dabei aber auch die oben aufgeworfenen Fragen berücksichtigt. Der

improvisatorische Charakter der Musik sowie der Versuch, die 15 Titel

als eine Gesamtheit für heutige Hörgewohnheiten erlebbar zu machen,

haben uns erlaubt, Teile umzustellen oder zu kürzen. Die letzte

Entscheidungsgrundlage für die Interpretation hat aber immer die Freude

an der Musik und der Kreativität gebildet - “Il Chominciamento di

gioia”.

“Zierliche Damen, ihr werdet, wie ich glaube, wohl

einsehen, der Sterblichen Verstand besteht nicht allein darin, die

Vergangenheit fest im Gedanken zu haben und die Gegenwart gehörig zu

kennen, sondern auch darin, durch das eine sowie durch das andere die

Zukunft vorhersehen zu können. Und dies ist bei ausgezeichneten Menschen

immer für einen Beweis der größten Weisheit angenommen worden.” (10.

Tag, 10. Novelle)

(“Il Decamerone” zitiert nach der Übersetzung von Schaum, Leipzig 1906)

Riccardo Delfino

The

queen bade bring instruments of music, for that all the ladies knew how

to dance, as also the young men, and some of them could both play and

sing excellent well. Accordingly, by her commandment, Dioneo took a lute

and Fiametta a viol and began softly to sound a dance; whereupon the

queen and the other ladies, together with the other two young men, began

with a slow pace to dance a branl; which ended, they fell to singing

quaint and many ditties. (First Day, Introduction).

In another place a lady sick for love is consoled with music:

Now

this Minuccio was in those days held a very quaint and subtle singer

and player and was gladly seen of the king; . . . (he) came to her and

having somedele comforted her with kindly speech, softly played her a

fit or two on a viol he had with him and after sang her sundry songs. . .

(Tenth Day, Seventh Novel).

On the one hand the ars musica

was no longer a speculative interpretation of the writings in monastic

scriptoria for the proof of the existence of God and his praise, but an

art applied in everyday life. On the other hand, just as Boccaccio had

raised vernacular and popular stories to a level of art, so the dances

of the lower classes, learned by ear and played extempore, might be

shaped into artistic performances.

Charming

ladies, as I doubt not you know, the understanding of mortals

consisteth not only in having in memory things past and taking

cognizance of things present; but in knowing, by means of the one and

otherof these, to forecast things future is reputed by men of mark to

consist the greatest wisdom. (Tenth Day, Tenth Novel).

English version by Uta Henning

Chominciamento di gioia

Virtuoso Dance-Music from the Time of Boccaccio's Decamerone

The

Black Death of 1348 in Europe brought death to some 25 million people.

It played a part in the ending of an out-dated way of life governed by

religious dogma and at the same time gave impetus to new currents of

thought in the cities of Northern Italy, where humanism, more democratic

forms of government and trade flourished. Nobles and citizens grew rich

with the cloth industry, which provided the necessary wealth for

cultural development, financing the establishment of universities where

discoveries were made by creative experiment and philosophical

investigation. The modern age was born.

Giovanni Boccaccio's Decamerone

of 1353 presents the story of ten young noblemen and noblewomen of

Florence who have withdrawn for ten days from the city, where the plague

rages, to find refuge at a country-house. There they entertain

themselves with singing, dancing and story-telling. They combine here

the medieval ideals of courtly love with the erotic in witty company.

The Decamerone gives a number of hints as to the musical habits of the time:

One of the earliest

manuscripts containing examples of such art dance-music comes from

Northern Italy and is found in the British Library in London (Ms.

29987). Apart from several madrigals, the language and notation of which

date the copy to c.1390, there are fifteen monophonic instrumental

pieces at the end of the manuscript. They are all in the characteristic

form of the dance-music of the period: several parti varying in number and form (parts independent of each other, often extempore in nature) always end with the same aperto (imperfect cadence) and with a chiuso (perfect cadence) after the repeat. The specific naming of the dances, moreover, - istanpitta for the first eight pieces, saltarello for the next four, and trotto

for the thirteenth - suggests the steps involved, stamping, hopping and

trotting. The last two pieces, however, raise questions as to their

suitability for dancing. The Lamento di Tristano and La Manfredina are solemn in mood, followed by quick variations, the so-called rotta. The trotto and the saltarelli can be identified most easily as dance-music, their structure being simpler and catchier than the istanpitte.

These last pose certain questions. First they stand apart from the

others in their length. Long extempore paraphrases of the melodic lines

and frequent leaps of a fifth or a fourth are quite in accordance with

the then instrumental customs derived from Arab culture and lie well

under the hand for instruments of the time, fiddle, recorder, harp, ud,

bagpipes and so on. Sometimes they give the istanpitte a touch of minimalism. On the other hand the parti

are sometimes lost in melodic flights of fancy, with changes of

accidentals which remind us of modern chromaticism, shifting rhythms and

a range of more than two octaves, nearly beyond the possibilities of

dance or performance on instruments of the period. It almost seems as if

the istanpitte represent experimental music of the fourteenth

century, seeking to define the boundaries of the new art of music. It is

the first time in the history of music that titles are supplied that

seem programmatical: Bellicha (the war-like woman), Parlamento (talk), Tre fontane (Three Springs), Ghaetta (the cheerful woman), In pro (Please), Principio di virtú (Principle of Virtue), Isabella and Chominciamento di gioia

(Beginning of Joy). lt seems possible that these compositions might

represent a great leap forward into the future, a forerunner of art for

art's sake.

The present recording includes all the instrumental

titles of Ms. 29987. In the interpretation the style of the time and the

appropriate instruments have been used, bearing in mind the questions

raised above. The extempore nature of the music and the attempt to

present the fifteen titles as an entity to modern audiences have allowed

the regrouping or shortening of certain parts of the manuscript. The

underlying principle of interpretation has always been that of joy in

music and of creativity - Il chominciamento di gioia.

(Quotations from the Decamerone are taken from the translation by

John Payne, London, 1903)

© 1994 Frédéric Castello

Ensemble Unicorn

Chominciamento di gioia

(Commencement de la Joie)

Musique de danse virtuose au temps du Décaméron

Dans

un contexte économique florissant, l'Italie du Nord fut, au XlVème

siècle, le cadre d'une riche vie culturelle dont la musique constitue

l'un des aspect les plus passionnants.

D'ailleurs, un célèbre ouvrage publié en 1353, le Décaméron

de Boccace, s'en fait parfois l'écho. La musique profane du siècle

précédent avait été marquée par les œuvres des troubadours, célèbres

pour leurs chansons dansées.

Au XlVème siècle, le nord de la

péninsule vit l'apparition d'un nouveau genre vocal profane: le

madrigal. Giovanni de Cascia, Gherardello da Firenze ou Jacopo da

Bologna par exemple l'illustrèrent en signant des pièces marquées par

une grande virtuosité tant vocale qu'instrumentale.

La musique

purement instrumentale n'était pas pour autant absente à cette époque,

le programme de ce CD en offre le témoignage. On y découvre des pièces

qui, outre leur dessein chorégraphique, présentent bien des richesses

mélodiques et des atmosphères très caractérisées que l'on devine sous

leur titres souvent évocateurs.

"Dioneo prit un luth et Fiametta

une viole et, avec douceur, ils entamèrent une danse ...", écrit

Boccace. Peut-être était-ce l'une de celles que l'on entend ici...

The

Ensemble Unicorn consists of five musicians specialising in early

music. Together with guest-musicians the Ensemble is dedicated to the

interpretation of music from the Middle Ages to the Baroque and of works

of their own. The aim is always lively authenticity, avoiding the

merely pedantic. An original feature of the Ensemble is the approach

towards contemporary popular music in new compositions and

interpretations of Medieval and Renaissance works, played on original

instruments. The compositions by the Ensemble are based on Medieval and

Renaissance dances, cantigas and chansons, reflecting the amalgamation

of Oriental and European cultural trends.

Michael Posch

The recorder-player Michael Posch was born in Klagenfurt and is musical director of the ensemble Musica Claudiforensis. He studied at the Carinthian Academy, at the Vienna Musikhochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst and at the Trossingen Musikhochschule. He is also a member of a number of early music groups, including Oni Wytars, Accentus and the Clemencic Consort.

Marco Ambrosini

Marco Ambrosini plays the keyed fiddle, fiddle, mandorla, kuhhorn, shawm and ocarina in the Ensemble. Born in Forli, he studied violin and viola at the Pergolesi Institute in Ancona and the Rossini Academy in Pesaro and subsequently founded the Oni Wytars early music ensemble. He is also a member of the Michael Riessler Tentett, Musica Claudiforensis, Accentus and the Clemencic Consort.

Riccardo Delfino

Riccardo Delfino, who plays the hurdy-gurdy, harp, bagpipe and dulcimer,

was born in Krefeld and studied in Göteborg. He has worked as a theatre

musician in Sweden and has a wide range of concert experience, notably

with Musica Claudiforensis, Accentus and Oni Wytars.

Thomas Wimmer

Thomas Wimmer plays the ud, fiddle, saz and vihuela d'arco.

Born in Waidhofen, in Austria, he studied viola da gamba and mandoline

in Vienna, specialising in historical plucked string instruments. He is

the founder of Accentus, which specialises in early Spanish music and has appeared in many concerts with ensembles such as Musica Claudiforensis, Oni Wytars and the Clemencic Consort.

Wolfgang Reithofer

Born in Neunkirchen, Wolfgang Reithofer studied percussion at the Vienna Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst. He is the founder and director of the Alpha Big Band and also serves as percussionist at the Vienna Volksoper. His concert experience includes frequent appearances with a number of early music ensembles, including Accentus, Musica Claudiforensis, Oni Wytars and the Clemencic Consort.