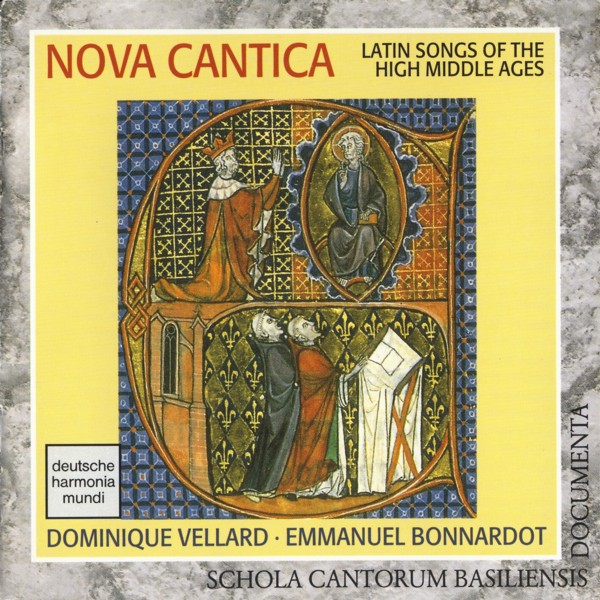

Nova Cantica. Latin Songs of the High Middle Ages

Dominique Vellard · Emmanuel Bonnardot

medieval.org

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) RD 77 196

1986, p. 1990

LATEINISCHE LIEDKUNST DES HOHEN MITTELALTERS

Ein-

und mehrstimmige Lieder des 12. Jahrhunderts aus Handschriften des

Klosters Saint Martial de Limoges

und Conductus aus nordfranzösischen

Kathedralen.

LATIN SONGS OF THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES

12th century monophonic and polyphonic songs in

manuscripts from the monastery Saint Martial de Limoges

and Conductus from cathedrals of Nothern France.

1. Da laudis, homo, nova cantica [3:49]

Conductus — Madrid, BN ms. 289 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

2. Annus novus in gaudio [4:34]

Versus — Paris, BN fl ms. 1139 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

3. Rex Salomon fecit templum [7:00]

Versus / Sequenz — Paris, BN fl ms. 3549 & ms. 3719 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

4. Letamini plebs hodie fidelis [2:56]

Benedicamus-Tropus — Paris, BN fl ms. 1139 |

D. Vellard

5. Natali regis glorie [3:17]

Conductus — Madrid, BN ms. 289 |

E. Bonnardot

6. Stirps Jesse florigeam [2:34]

Benedicamus-Tropus — Paris, BN fl ms. 1139 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

7. Iubilemus, exultemus [3:27]

Benedicamus-Tropus — Paris, BN fl ms. 1139 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

8. Letabundi iubilemus [3:25]

Benedicamus-Tropus — Paris, BN fl ms. 1139 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

9. Ex Ade vitio [6:21]

Conductus — London, ms. Egerton 2615 |

E. Bonnardot

10. Noster cetus [3:58]

Benedicamus-Tropus — Paris, BN fl ms. 1139 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

11. Natus est [2:51]

Conductus — London, ms. Egerton 2615 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

12. Dulcis sapor novi mellis [5:24]

Benedicamus-Tropus — Paris, BN fl ms. 1139 & Apt, ms. 6 |

D. Vellard · E. Bonnardot

13. Alto consilio [5:34]

Conductus — London, ms. Egerton 2615 |

D. Vellard

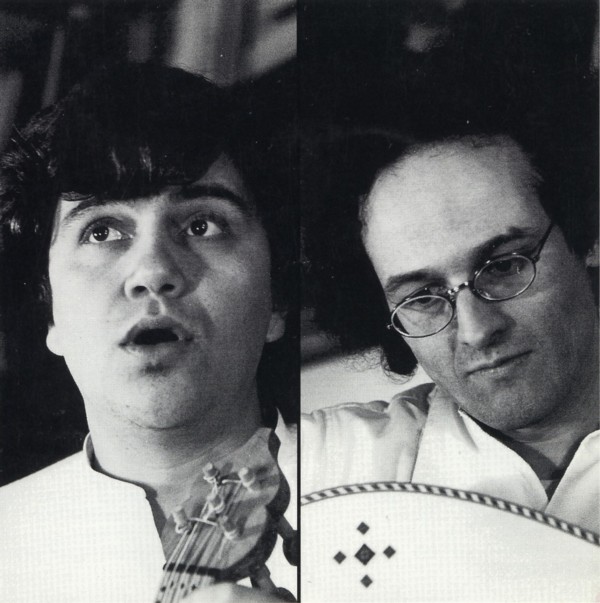

Dominique Vellard & Emmanuel Bonnardot

Durch

ihre Tätigkeit im Ensemble Gilles Binchois haben Dominique Vellard und

Emmanuel Bonnardot ihre gemeinsamen musikalischen Vorlieben entdeckt und

widmen sich als Duo dem Gregorianischen Gesang und der liturgischen

Musik des 11. und 12. Jahrhunderts. Sie unterrichten im Bereich

mittelalterlicher Musik an der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, dem

Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique in Lyon und dem Centre de

Musique Médiévale in Paris. Bei vielen europäischen Rundfunkanstalten

und mehreren Schallplattenfirmen machen sie regelmäßig Aufnahmen.

Die

ästhetischen Grundlagen zur Interpretation der Werke dieser Einspielung

sind das Ergebnis einer langen Zusammenarbeit mit Wulf Arlt, auf der

Basis seiner Analysen zu jedem einzelnen Stück und seiner genauen

Kenntnis der handschriftlichen Überlieferung.

It's

thanks to their work with the Ensemble Gilles Binchois, Dominique

Vellard and Emmanuel Bonnardot have found a way to express their musical

affinities to the best advantage. As a duo, they sing Gregorian Chant

and liturgical music of the 11th and 12th Centuries. They teach medieval

music in institutions such as the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, the

National Conservatory of Music in Lyon and the Center for Medieval Music

in Paris and record regularly for radio stations throughout Europe and

for diverse record companies.

Their approach to interpretation of the

repertoire for this record is the result of long discussions with Wulf

Arlt and analysis of each piece and with his understanding of the

written tradition.

Ⓟ 1990, harmonia mundi, D-7800 Freiburg

© 1990, Schola Cantorum Basiliensis

Aufnahme/Recording: Pere Casulleras

Aufgenommen/Recorded: 1.-5. X. 1986

Kirche/Church Amsoldingen/Kanton Bern (CH)

Kommentar/Liner notes: Wulf Arlt

Übersetzungen/Translations: Marie-José Brochard, Nicoletta

Gossen, Anne Smith & Hartwig Thomas, Marco Stocco, Lorenz Welker

Titelseite/Front cover picture:

Initial(e) C (Beginn von/Beginning of Ps. 97: „Cantate Domino canticum novum“).

Paris Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds latin, Ms. 10525, fol. 192r (Anfang 13. Jh./Beginning of 13th century)

Quellen/Sources:

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds latin, Ms. 1139: # 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds latin, Ms. 3549: # 3

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds latin, Ms. 3719: # 3

Apt, Trésor de l'église, Ms. 6: # 12

London, British Library, Ms. Egerton 2615: # 9, 11, 13

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, Ms. 289 #1, 5

(Doppelt aufgeführte Stücke wurden nach zwei Quellen ediert.

/ Two sources were used for the edition of the pieces listed twice)

Redaktion/Editing:

Lorenz Welker, Thomas Drescher (SCB)

Rudolf Moratscheck (dhm)

All rights reserved

HARMONIA MUNDI D-7800 FREIBURG

Nova Cantica

Das

Erstaunlichste an der neuen Mehrstimmigkeit und der neuen Liedkunst,

die im Frankreich des frühen 12. Jahrhunderts — einer Zeit des Aufbruchs

im Denken und Tun — den romanischen Kirchenraum mit neuem Klang

füllten, ist ihre Vielfalt: ein Reichtum musikalischer Gestaltung, der

sich auch heute wieder unmittelbar erschließt.

Bis dahin war die

Mehrstimmigkeit eine klangliche Erweiterung älterer Gesänge nach

etablierten Spielregeln. Jetzt ging es um neue Texte der liturgischen

Dichtung. Ihre Vertonung führte auf immer weitere Möglichkeiten der

Stimmverbindung, des Klangs und der formalen Gestaltung in der

musikalischen Formulierung der Verse, und das läßt sich in der ältesten

Aufzeichnung der Jahre um 1100 von Satz zu Satz beobachten. Nur ist der

faszinierende Reichtum dieses Komponierens im Konzert unserer Tage

weithin erst noch zu entdecken. Und ebenso verhält es sich beim Lied.

Das

Lied selber war eine Entdeckung der Wende vom 11. zum 12. Jahrhundert.

Strophische Texte zur gleichen Melodie gab es immer schon und

kunstvollen Reim seit den Anfängen des Mittelalters. Nun aber kam es aus

der Verbindung der sprachlichen Fügung mit einer freien musikalischen

Gestaltung zu einem eigentlichen Lied im emphatischen Sinne des Wortes.

Die

liturgischen Lieder sind das lateinische Gegenstück zum weltlichen Vers

in der provenzalischen Kunstsprache, der am Anfang des europäischen

Minnegesangs steht und mit den Gedichten Wilhelms von Aquitanien

(1071-1127) beginnt. Auch im Provenzalischen hatte zunächst jeder Text

seine eigene Weise. Doch sind die Melodien der Trobadors nur zum

geringsten Teil und erst in späten Aufzeichnungen erhalten. Im Latein

hingegen setzt die schriftliche Überlieferung schon am Anfang des 12.

Jahrhunderts ein. Hier sind die Aussagen einfacher, die Strophenformen

jedoch vielfältiger, und ihre musikalische Formulierung zeigt ein

ungleich breiteres Spektrum der kunstvollen Gestaltung.

Die neue

Mehrstimmigkeit ist vor allem aus dem Süden überliefert, die neue

Liedkunst hingegen auch aus dem Norden Frankreichs. Und da unsere

Aufnahme aus dem Wunsch entstand, zum ersten Mal die Vielfalt des Neuen

aufklingen zu lassen, mit dem der Übergang vom 11. bis 12. Jahrhundert

zu einer gewichtigen Zäsur in der Geschichte der europäischen Musik

wird, sind der Süden und der Norden vertreten.

Am Beginn steht mit Da laudis, homo, nova cantica

[#1] ein extremes Beispiel für eine subtile musikalische Formulierung,

die durch die formale Gestaltung wie durch die Aussage des Gedichtes

geprägt ist. Der Text fordert dazu auf, NOVA CANTICA anzustimmen: neue

Lieder als Antwort auf die neuen Freuden der Weihnacht. Die Musik nimmt

die Gliederung des Gedichtes einschließlich der Zäsuren sowie den

Sprachfall auf, sie unterstreicht im hohen Neueinsatz am Anfang des

zweiten Verses auf dem Spitzenton die begründende Wiederholung sowie

durch das einzige Melisma auf „sunt“ das Ereignis („Singe die neuen Gesänge, weil Dir neue Freuden gegeben sind“)

und sie intensiviert die Wiederholungen im zweiten Teil der Strophe mit

den Mitteln der Musik. Die Eigenheiten dieser besonderen Formulierung

stimmen auch bei den weiteren Strophen in Text und Musik so überein, daß

wohl nur der gleiche beide zum Lied gefügt haben kann.

Das Gegenbeispiel einer raffiniert einfachen musikalischen Gestaltung zum Vortrag vieler Strophen bietet Natali regis glorie [#5]. Letabundi iubilemus

[#8] bringt für die zweite Strophe eine weit angelegte

improvisatorische Melismatik und damit fürs ganze Lied eine dreiteilige

Anlage (ABA). Ex Ade vitio [#9] verbindet die verschiedenen

Möglichkeiten im Vortrag der komplexen sprachlichen Fügung. Und im

vorletzten der einstimmigen Lieder, Natus est [#11], einem Geleitgesang zu einer Lesung der Messe, dominiert das dramatische Moment.

Auch

in den mehrstimmigen Liedern steht die eher formale Zuordnung von Musik

und Text neben einer so individuellen Lesung wie sie Iubilemus, exultemus, intonemus canticum

[#7] bietet — ebenfalls bis zum Aufnehmen einzelner Aussagen in der

musikalischen Formulierung. Mit der unterschiedlichen Anlage und

Funktion der Stimmen wird der Charakter der Stücke auch durch den je

anderen Gebrauch der Zusammenklänge geprägt: einmal konsonanter (wie in

#3, #7 oder #10) und ein andermal mit verblüffenden Dissonanzen aus der

freien Führung der Stimmen (wie im Refrain von [#2] oder in [#12]). Und

bei einer Interpretation dieser Sätze, die von den Eigenheiten der

Gestaltung ausgeht und sich von der Akustik eines romanischen

Kirchenbaus leiten läßt, kommt es zu erstaunlichen Unterschieden auch in

der Zeiterfahrung, die diese Musik vermittelt.

Ganz für sich steht bei den mehrstimmigen Sätzen Stirps Jesse

[#6]. Hier wird über einem älteren Gesang ein neuer Text vorgetragen,

der die Worte des „Benedicamus Domino“ in der Unterstimme interpretiert.

Abermals dominiert ein dramatischer Grundzug, diesmal jedoch aus der

Herkunft dieser Struktur; denn in ihr spiegelt sich eine schriftlose

Praxis des freien Vortrags neuer Texte über bestehenden Gesängen, die

bis ins späte Mittelalter nachzuweisen ist.

Das neue freie

Komponieren steht am Anfang einer langen Geschichte, in der die

einstimmige Gestaltung mehr und mehr an Gewicht verlor. In der Kunst des

12. Jahrhunderts, die alsbald gegenüber den neuen Möglichkeiten einer

Komposition mit fixierten Rhythmen in den Hintergrund trat, halten sich

die Gestaltung in der Melodie und im Klang die Wage. Und wie unsere

Auswahl mit einer Aufforderung zu NOVA CANTICA begann, so endet sie mit

der eindrücklichsten Kunstgestaltung im Einstimmigen aus diesem

Aufbruch: mit dem weit angelegten Alto consilio [#13], das im

gedankenreichen Gedicht wie in der musikalischen Formulierung und nicht

zuletzt im Zusammenspiel beider Alt und Neu zu einer einzigartigen

Verbindung fügt.

Die meisten Lieder wurden für die Aufnahme neu

nach den Quellen des 12. Jahrhunderts editiert — dazu und zu einzelnen

Interpretationsfragen der eingehende Bericht im Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis

10 (1986). Die übrigen liegen in der Edition einer Handschrift des 13.

Jahrhunderts vor, deren einstimmiger Bestand in die Mitte des 12.

Jahrhunderts zurückgeht: W. Arlt, Ein Festoffizium des Mittelalters aus Beauvais in seiner liturgischen und musikalischen Bedeutung (Köln 1979).

Wulf Arlt

Nova Cantica

The most astonishing feature of the new polyphony

and the new song style, which in the early 12th century — a time of

innovation in both thought and action — filled the French Romanesque

church with new sounds, is their variety: a wealth of musical structure

which can readily be understood even today.

Up until that time

polyphony was a vertical expansion of older songs in accordance with

established rules. Then, however, new liturgical poems became involved.

Their settings led to more and more possibilities of combining the

voices, of utilizing harmony in the broadest sense of the word, and of

formally organizing the musical formulation of the text. This may be

observed as it were piece by piece in the oldest source from around

1100. To a great extent, however, the fascinating wealth of this kind of

composition has yet to be explored in concert today. This is equally

true for the song.

The song was a discovery made at the turn of

the 11th to the 12th century. Strophic texts to the same melody had

always existed and with the advent of the middle ages artistic rhyme

schemes made their appearance. From the synthesis of the textual

structure with a free musical organization, however, the Lied in the later meaning of the world evolved.

The

liturgical songs are the Latin counterpart to the secular verse in the

Provençal poetic language, which initiated the European Minnesang

beginning with the poems by William of Aquitaine (1071-1127). In

Provençal each text had its own tune to begin with. Only the smallest

fraction of the trobador melodies survive today, and even that only in

late manuscripts. For the Latin songs, however, the written transmission

started already at the beginning of the 12th century. The content of

these works is simpler; their strophic forms, though, are more varied

and their musical formulation shows a much wider spectrum of artistic

organization.

The new polyphony stems primarily from the South of

France, whereas the new song style comes also from the North. Our

recording originated with the desire of introducing the full variety of

these innovations to today's listener for the first time, innovations

which make the transition from the 11th to the 12th century an important

turning point in the history of European music. Therefore both the

South and the North are represented.

At the beginning an extreme example of a subtle musical formulation is found, Da laudis, homo, nova cantica

[#1], one which is imbued with the formal organization of the poem as

well as with its content. The text is an invitation to sing NOVA

CANTICA: new songs as a response to the new joys of Christmas. The music

incorporates the phrasing of the poem, including its caesuras and its

intonation. It emphasizes the repetition of the causal subordinate

clause by the high entrance on the uppermost note at the beginning of

the second line and, in addition, stresses the event by the single

melisma on the word “sunt” (“Sing the new songs because

new joys have been given unto you”). It intensifies the repetitions in

the second section of the strophe by musical means. The characteristics

of this special formulation also fit both the text and music of the

other strophes so well that one person must have been responsible for

both in creating this song.

A contrasting example of a ingeniously simple musical organization for the performance of many strophes is proffered by Natali regis glorie [#5]. The second strophe of Letabundi iubilemus [#8] is a broadly-dimensioned, improvisational, melismatic section; the whole song thus has a ternary form (ABA). Ex Ade vitio

[#9] combines the various possibilities in its presentation of a

complex textual structure. In the second to last of the monophonic

songs, Natus est [#11], whose function was to accompany a lesson of a mass, the dramatic moment is predominant.

Also

in the polyphonic songs a more formal coordination of music and text

stands side by side with extremely individual lessons such as lubilemus, exultemus, intonemus canticum

[#7], which also reflects individual statements of the text in its

musical formulation. Because of the difference in disposition and

function of the voices, the character of the pieces is also influenced

by the various kinds of vertical intervallic structure used: sometimes

it is more consonant (as in #3, #7 or #10) and sometimes it displays

amazing dissonances resulting from free voice-leading (as in the refrain

of #2 or in #12). Astonishing differences — also in the experience of

subjective time as communicated by this music — result from an

interpretation of these pieces which takes their structural

characteristics into account and yields to the acoustics of a Romanesque

church.

Stirps Jesse [#6] stands alone among the

polyphonic pieces. In it a new text is presented above an older melody

which interprets the words of the Benedicamus Domino found in the

lower voice. Once again a dramatic feature predominates, this time

stemming from this structure's origin. It reflects an unwritten practice

of singing new texts over existing melodies, a practice that lasted

into the late middle ages.

The new free method of composition

stands at the beginning of a long tradition, in which the monophonic

structure gradually lost importance. In the art of the 12th century,

which was soon to withdraw into the background with the advent of the

new possibilities of composing with fixed rhythms, the structure of the

melody and of the harmony (in the broadest sense of the word)

counterbalanced one another. Just as our selection began with an

invitation to sing NOVA CANTICA, it ends with the most impressive

monophonic work from this period of innovation: with the

broadly-dimensioned Alto consilio [#13], a unique fusion of a

poem full of ideas, a musical formulation, and, last but not least, an

interaction between both old and new.

For this recording a new

edition from the 12th century sources was made of most of the songs.

More information about this and concerning certain questions dealing

with interpretation may be found in the comprehesive article in the Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis

10 (1986). The rest is taken from the edition of a 13th century

manuscript, whose monophonic repertoire extends back to the middle of

the 12th century: W. Arlt, Ein Festoffizium des Mittelalters aus Beauvais in seiner liturgischen und musikalischen Bedeutung (Cologne, 1970).