medieval.org

glossamusic.com

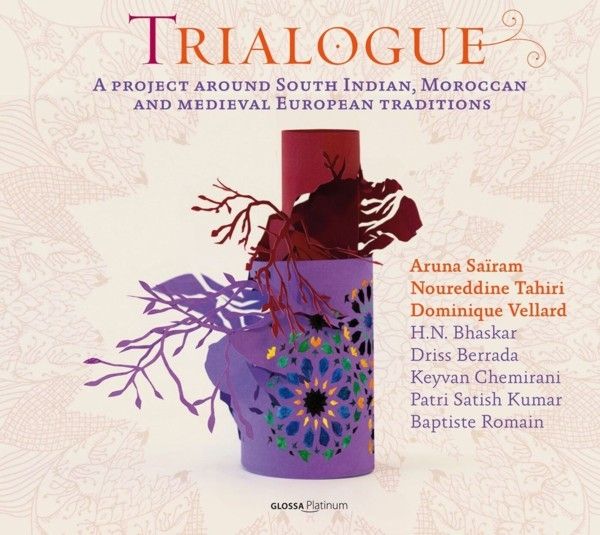

Glossa Platinum GCD P32306

2012

1. Al-Adhân [2:36] Call to prayer (Islamic tradition)

2. Benedicam [2:52] Gradual (plainchant)

3. Lalitha Saharsaranamam [3:03] Vedic recitation

4. [13:30]

Kanthamam Kathirkamam · Mayuram Vishwanatha SASTRI, (Raga Sindhu Bhairavi)

Alleluia, imperatrix egregia · Anonymous

5. Al Kalbou [4:54] Mowale (naawande mode)

6. Puis que ma dolouri [3:38] Guillaume de MACHAUT, virelai

7. Raga Amritavarshini [6:50] Muthuswami DIKSHTAR

8. Entre terre et ciel [10:03] Baptiste Romain, instrumental · CSM 260

9. Ihesus Cristz [5:11] Guiraut RIQUIER

10. Raml el maya [3:54] Arabo-Andalusian repertoire

11.. Eppo Varuvaro [3:53] Gopaalakrishna BHAARATIYAAR

12. [7:18]

Por nos virgen madre · ALFONSO X el SABIO, cantiga · CSM 250

Chamss el achiya · Arabo-Andalusian repertoire

13. [11:19]

Shanti · Setumaadhava RAO

Salam · Improvisation

Agnus Dei · Plainchant

INDIAN TRADITION

Aruna Saïram, voice

H. N. Bhaskar, violin

Patri Satish Kumar, mridangam

MOROCCAN TRADITION

Noureddine Tahiri, voice

Driss Berrada, oud

EUROPEAN MEDIEVAL REPERTOIRES

Dominique Vellard, voice (& oud)

Baptiste Romain, fiddle (& voice)

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

Recorded in the church of Mont-Saint-Jean (Bourgogne, France) on 6-9 June 2011

Engineered by Jean-François Felter (ADMson)

Produced by Jean-François Felter and Ensemble Gilles Binchois

Executive producer: Carlos Céster

Art direction & design: oficinatresminutos.com

Editorial direction: Carlos Céster

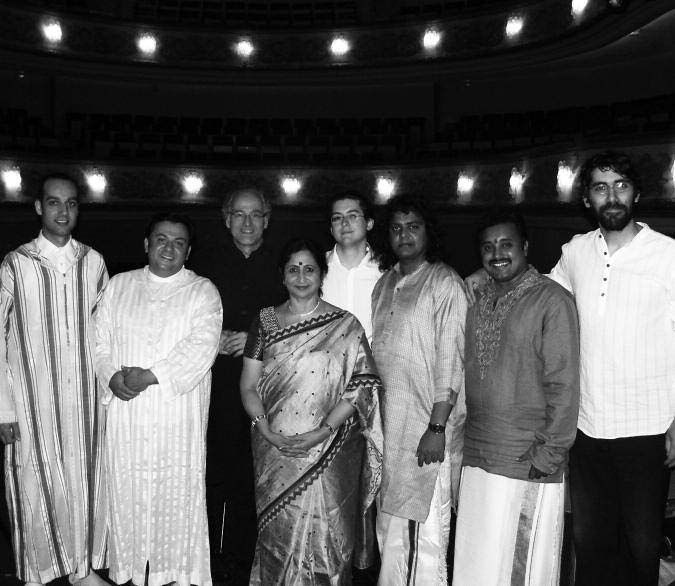

All photographs taken by Anne-Marie Vellard in Chambéry (Espace Malraux) on 4 June 2011,

except the last one, taken by Stéphanie Hammarstrand in Dion (Grand Théâtre) on 7 June 2011

Editorial assistance: María Díaz, Mark Wiggins

edition produced by glossa music s.l. for note 1 music gmbh

℗ & © 2012 note 1 music gmbh

‘Trialogue’

«L’homme est un vase que Dieu a créé pour

lui-même et qu’il a rempli de son inspiration afin

d’y accomplir ses œuvres» (Hildegard von Bingen)

I. Une recherche, une rencontre...

Depuis le milieu du XIXe siècle, de nombreux musiciens et

musicologues ont cherché dans les traditions musicales

extra-européennes des clés pour la compréhension

du chant grégorien. Ce fut également ma démarche:

aller puiser à la source des musiques de tradition orale les

gestes vocaux universels permettant de transmettre l’esprit et

l’émotion du texte par le chant.

Si dans notre siècle la musique a perdu une grande partie de ses

fonctions, pour l’homme du Moyen Age son rôle est double,

personnel et social. Porte vers le Divin, moyen de connaissance de la

perfection de la création et de la place de l’homme dans

cette création, la musique a également un rôle

d’intégration de l’homme dans son milieu social,

pour le former et le divertir.

Dans la majorité des grandes traditions mystiques, le chantre

est vecteur d’une force qui le traverse; tout son art consiste

à transmettre ce qui lui est donné, mais la

prétention lui est interdite, elle ôterait toute valeur

à son chant. Ce chant libéré de l’ego du

chanteur possède alors un pouvoir qui lui est propre,

l’une de ses principales fonctions est de toucher le plus profond

de nous-mêmes en brisant nos résistances. Et c’est

à la recherche de cette vérité profonde du chant,

du sens et de la raison qui ont mené à la création

des répertoires que j’interprétais, que la

confrontation avec d’autres traditions musicales m’a paru

indispensable, sollicitant de moi une exigence artistique accrue pour

pouvoir dialoguer de pair avec des artistes établis dans une

tradition forte et séculaire.

Après plus de 15 ans consacrés à la musique du

Moyen Age, j’ai eu l’opportunité de rencontrer Aruna

Saïram et de construire avec elle un premier programme de concert.

Nous avons pris le temps de rechercher dans nos répertoires les

pièces qui semblaient trouver un écho dans

l’oreille de l’autre et, petit à petit, avons pu

établir un riche dialogue musical et humain. Cette amitié

et connivence musicale a généré une trentaine de

concerts en Europe, Inde, Maroc, et Malaisie ainsi qu’un

enregistrement pour EHU intitulé Sources, paru en 1999.

Notre rencontre en 2002 avec le chanteur marocain Noureddine Tahiri a

été le ferment d’un nouveau programme ayant pour

seule direction le plaisir du dialogue, chaque tradition, chaque

religion, s’enrichissant de l’écoute de

l’autre. Il en est ressorti un message sous-jacent qui

s’est révélé dans la dernière

pièce de cet enregistrement, celui d’une paix pour tous

espérée par chacun.

Afin de poursuivre cette merveilleuse aventure musicale et humaine,

nous avons ressenti l’envie d’y associer les

instrumentistes qui nous accompagnent régulièrement dans

nos traditions respectives. Cela nous permet d’aborder

d’autres aspects de nos répertoires qui ne se suffisent

pas du chant à voix nue et qui mettent en évidence de

nouvelles correspondances. Nous avons donc invité au concert des

voix les instruments mélodiques: le violon pour le chant

carnatique, le oud pour la musique arabe et la vièle à

archet pour les traditions médiévales, ainsi que les

percussions: mridangam et daf, qui sont un apport considérable

pour la confrontation des trois traditions sur le plan rythmique.

Grâce à une résidence de création à

Chambéry, en juin 2011, chacun a pris le temps de proposer des

pièces qui puissent se correspondre tant sur le plan du contenu

textuel que sur le plan modal ou rythmique. Que ce soient des chants de

louange pure ou bien l’expression humaine de l’amour

côtoyant celle de l’amour mystique, le programme se

déroule comme s’est déroulée la rencontre:

par la mise en œuvre progressive des moyens musicaux: le chant

lancé à voix seule est petit à petit rejoint par

l’instrument mélodique qui lui répond, qui

l’enrobe pour l’emporter vers un autre mode

d’expression qui sollicite toutes les forces terrestres (les

percussions sont ici comme l’assise terrestre du chant) où

prendre un élan qui le libère de ses limites, de ses

frontières.

Cet enregistrement est le point d’épanouissement que tout

musicien cherche à atteindre le plus souvent possible dans sa

carrière, il est le témoin d’un moment de pure

entente à travers la musique et, par cela même, porteur

d’un fort message de dialogue, de respect et

d’amitié entre les trois grandes traditions ici

réunies, tant sur le plan musical que spirituel.

DOMINIQUE VELLARD

II. Entre terre et ciel...

Benedicam Dominum in omni tempore: semper laus eius in ore meo.

«Je bénirai le Seigneur en tout temps: sa louange est

toujours en ma bouche.» In ore meo... Le mot latin os (qui

désigne la bouche en l’un des chants de cette longue

chaîne fraternelle) mérite qu’on le regarde,

qu’on le contemple: à sa simplicité naturelle de

monosyllabe, il ajoute en effet cet avantage que son unique voyelle

prend exactement la forme de la réalité qu’il

signifie. Et pour peu que l’on ait l’oreille aussi fine que

le regard, on entendra bientôt se dessiner une constellation

sonore entre oral, orée, aurore, seuls les deux premier

mots étant réellement apparentés, mais

qu’importe. Reste qu’avec ces trois mots-là nous

sommes au cœur de l’événement – du

miracle – dont le présent enregistrement nous offre

l’évidence, asseyant ainsi au plus intime de

nous-même la certitude que l’avenir commun de

l’humanité peut se construire et se reconstruire sans

cesse à voix nue. De fait, les voix convoquées ici nous

convoquent à leur tour en ce lieu commun d’humanité

où l’oralité, dans une émanation aussi

maîtrisée que libre, évoque les origines. Orée,

aurore... Lorsqu’il ouvre la bouche en vérité,

l’homme ouvre tout aussitôt les persiennes du monde. Ce qui

se donne à entendre, alors, fait merveilleusement jour et donne

à penser que des jours meilleurs ne sont pas une illusion.

Ici se donne une fête où les voix sont convives.

L’on entend tout le bonheur qu’elles ont de se rencontrer,

mais comme se rencontrent des sages; de se mesurer les unes aux autres,

mais sans nulle arrière-pensée de domination; de

s’amuser, s’il se peut dire, les unes aux autres –

musique oblige! –, mais dans la plus grande considération

mutuelle. Ici l’on fait commerce de joie, d’une haute joie

dont chaque voix est pour sa compagne l’échanson. Parmi

ces commensaux qui parviennent à l’unanimité en se

faisant l’offrande mutuelle de leur patrimoine respectif, le plus

enraciné dans la terre et dans le ciel tout ensemble, il fait

bon vivre, et l’on entrevoit qu’un bien vivre ensemble est

possible. Ce qui est nous donné à entendre en cette suite

est d’une extrême clarté, et sans doute est-ce cette

clarté, cette espèce de nudité qui

d’emblée nous convainquent, qui nous dépaysent

aussi, tant nous sommes désormais saturés par des modes

d’oralité dévalués, déchus de leur

noblesse primitive. D’où qu’il parte, et de quelque

tradition qu’il soit le porteur, l’homme qui intervient en

cette «conversation» est fondamentalement le même: le

premier homme au premier jour, la première voix.

Les chants que ce festival, cette grande fête musicale, met en

éventail sont autant de «béatitudes»

prononcées sur les justes, les doux, les artisans de paix;

autant d’invitations à la prière, la prière

étant elle-même, sans doute, la toute première

intonation première de l’homme. À chaque fois

– à chaque voix – c’est la même

histoire, le même commencement, la même tentative, mais

exaucée par le silence qui la promeut, qui l’espace, qui

la suit. C’est la même humanité native qui se

déclare. C’est la même transcendance qui se devine,

lors même que nous demeurent incompréhensibles –

mais si provisoirement, au fond! – les idiomes qui la

désignent, ou plutôt qui l’enluminent avec

révérence. Une voix s’élève,

s’affirme, s’assure d’une assise à la fois

résistante et souple, comme le ferait un marcheur: elle se

trouve, au sens le plus concret du terme, une espèce de

«firmament» – firmamentum –

c’est-à-dire un ciel intérieur, mais solide et

propice, en conséquence, à maintes excursions plus

audacieuses.

L’itinéraire qu’elle décrit dans

l’échelle des sons semble se traduire insensiblement dans

le registre visuel: on la voit, et l’on voit se déployer

avec elle – construit par elle –un paysage entier! Elle

essaie, elle s’aventure, elle interroge, mais avec une

agilité qui laisse à présumer qu’elle est

déjà passée maintes fois par le sentier

qu’elle emprunte. L’appui une fois bien assuré, elle

tâte des montagnes, elle s’étourdit à

plaisir, comme un oiseau de grande envergure, de la vibration presque

plane de ses rémiges, elle fuse, elle explore des ravins, des

canyons subits, des régions d’ombre majeure, elle

s’expose au grand soleil: le relief entier du monde surgit au

gré de ses évolutions qui l’inventent, il

naît de sa marche même qui décide de lui avec une

liberté souveraine. Au-delà du raisonnement, et par la

seule grâce de la chair qu’elle convoque toute

entière en son émission, la voix nue prouve

l’existence de l’Altitude qu’elle atteint. La voix

est ici, et simultanément, un toucher-terre et un toucher-ciel:

c’est parce qu’il est fermement campé sur son

«firmament» le plus intime que le chanteur peut

«déclarer» – le son est lumière

– l’orientation spontanée de l’homme vers un

«Toi» qui le dépasse.

Dans un moment tout à fait premier de son histoire universelle,

et que chaque acte de chant particulier réédite

(c’est d’ailleurs ce qui le rend si émouvant),

l’homme n’a que sa voix, que l’instinct de sa voix

pour toucher son Auteur: allant ainsi tout droit au Vif, fût-ce

à travers d’innombrables détours, la voix, dans sa

simplicité, est une espèce d’arme blanche.

Âge d’or (au demeurant toujours accessible) que celui

où l’homme n’en avait point d’autre que

celle-là! S’il y a du sacré, en la circonstance, il

ne saurait donc se concevoir comme une valeur surajoutée: il

réside déjà tout entier dans la posture de

l’acte vocal lui-même et dans la manière dont il

s’arrime à l’Invisible qu’il tutoie, comme au

texte vénérable qu’il embouche. Tout ce qui se

donne à entendre ici tient magnifiquement debout. L’on

pense aux mots de Rilke, dans l’un de ses Sonnets à

Orphée: «Sur ce qui passe et qui s’en va, avec

plus de largesse et plus de liberté, ton chant inaugural reste

et persiste!... Seul sur la terre, le chant célèbre et

sanctifie.»

À travers sa voix mise en train par l’auxiliaire

instrumental (lequel devient parfois, et longuement, le protagoniste),

l’homme manifeste sa condition première de jongleur,

autrement dit d’enfant. Rien de plus sérieusement enfantin

que le rythme: la main qui l’imprime et le scande est aussi

souveraine que la voix. Dans le fondu enchaîné des

modalités les plus originelles, des intervalles musicaux les

plus astreints ou les plus exubérants, les grandes traditions

religieuses de l’humanité s’avèrent

être étonnamment perméables les unes aux autres:

elles s’entendent, elles sont d’intelligence, sans pour

autant se confondre. Les échelles sonores sont ici la

règle du jeu. Elles sont les mots de passe que les partenaires

de cette symphonie d’humanité saisissent au vol comme

s’ils se connaissaient depuis toujours, leurs chants se faisant

allusion les uns aux autres pour se donner la paix –pour nous la

donner. Car c’est au fond le même Nom divin –

Père et Mère à la fois – que les

poèmes mystiques de l’Islam, de l’Inde et de

l’Occident chrétien caressent à travers des images

et des invocations diverses, c’est de la même

Dame-Beauté qu’ils s’enchantent, c’est de la

même quête brûlante d’amour qu’ils nous

entretiennent. Qu’ils soient de haute antiquité ou quasi

contemporains, les aspirations qu’ils exhalent témoignent

d’une bouleversante continuité. Tissée de textes

originaires des points les plus extrêmes du monde, et ce, de

façon de plus en plus serrée à mesure

qu’elle s’achemine vers sa résolution, la

cantilène universelle élabore un grand traité de

paix. Celui-ci laisse à penser que la voix, dans la jubilation

et la savante ingénuité de son geste, est bien la

maîtresse d’un banquet futur et l’avant-coureuse

d’une civilisation telle que nul n’en soit exclu. À

l’horizon d’un monde qui peine à construire son

unité et qui prend parfois prétexte de la transcendance

même pour légitimer les violences les plus aveugles, le

moment de grâce ici diffusé nous indique de quel

côté se trouve notre espérance-vie.

FRANÇOIS CASINGENA-TREVEDY, OSB.

1. Al-Adhán —

Call to prayer (Islamic tradition)

Nouredinni Tahiri, voice

The call to prayer is the symbolic sound of the Islamic tradition;

whilst turning towards Mecca, the muadhdhin (or muezzin)

recites the adhân five times on each day, in order to

announce to the faithful the arrival of the hour for ritual prayer.

L’appel à la prière est le symbole sonore de la tradition islamique ; le

mouadhdhin (ou muezzin) le chante 5 fois par jour, en se tournant

vers La Mecque, pour annoncer aux fidèles l’arrivée de l’heure de la

prière rituelle.

2. Benedicam —

Gradual (plainchant)

Dominique Vellard, voice

Performing this Gregorian gradual in the seventh mode has been made

feasible by way of a linked reading involving two manuscripts: that

from Laon (end of the 9th century) marks out the rhythmic pattern

(using the notation of neumes) and that from Gaillac (11th century)

provides the melody.

L’interprétation de ce graduel grégorien du 7ème mode est rendue

possible grâce à la lecture conjointe de deux manuscrits : celui de

Laon (fin du ixe siècle) en indique la conduite rythmique (écriture

neumatique) et celui de Gaillac (XIe sièmecle) en donne la mélodie

3. Lalitha

Saharsaranamam —

Vedic recitation

Aruna Saïram, voice

A Vedic recitation, whose title means literally “The one thousand

divine names of the Universal Mother”. These chants have been

chanted by many peoples, even up till today, with the aim of attaining

peace of mind and equanimity.

Récitation védique, « les mille noms de la Mère universelle ». Ces

versets sont récités par de nombreuses personnes, encore de nos jours,

pour obtenir la paix de l’esprit et la sérénité.

4. Kanthamam

Kathirkamam / Alleluia —

Mayuram Vishwanatha SASTRI (Raga Sindhu Bhairavi) / Anonymous

Aruna Saïram, voice

Dominique Vellard, voice

H.N. Bhaskar, violin

Patri Satish Kumar, mrindangam

Baptiste Romain, fiddle & voice

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

This Tamil-language poem celebrates the Divine Muruga who resides in a

temple in Kadirkamam, a village in Sri Lanka. The work was composed by

Mayuram Vishwanatha Sastri, in the Sindhu Bhairavi raga. From a

compositional point of view the Alleluia is a late work, and

one which alternates between free and rhythmic sections (Hohenfurt

Abbey, 1410).

Ce poème en langue Tamil célèbre le Divin Muruga qui réside dans

un temple à Kadirkamam, un village du Sri Lanka. La composition

est de Mayuram Vishwanatha Sastri, dans le raga Sindhu

Bhairavi. L’Alleluia est une composition tardive qui alterne parties

libres et parties rythmées (Abbaye de Hohenfurt, 1410).

5. Al Kalbou —

Mowale (naawande mode)

Nouredinni Tahiri, voice

Driss Berrada, oud

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

“The heart” (mawwal,

maqam nahawand). The mawwal is a free chant and the maqam

(or mode) nahawand is of Iranian origin. This particular piece

is sung during Sufi ceremonies in the style of the Samâ.

« Le cœur » (mowale, mode naawande). Le mowale est un chant

libre. Le mode naawande est d’origine iranienne. Cette pièce est

chantée lors de cérémonies Soufi dans le style du Samâ

6. Puis que ma

dolour —

Guillaume de MACHAUT (virelai)

Dominique Vellard, voice

Baptiste Romain, fiddle

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

Born in Rheims, Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377) is unquestionably the

preeminent figure of the 14th century, as outstanding as a poet as he

was a musician, and he was celebrated by his contemporaries as

“the master of all melody”.

Originaire de Reims, Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377) est sans

conteste la grande figure du XIVe siècle, aussi grand poète que

musicien ; il est célébré par ses contemporains comme « le maître de

toute mélodie ».

7. Raga

Amritavarshini —

Muthuswami DIKSHTAR

Aruna Saïram, voice

H.N. Bhaskar, violin

Patri Satish Kumar, mrindangam

The composer Muthuswami Diksthar (17th-18th centuries) once travelled

to a drought-ridden area to find a people wasting away from thirst and

hunger. He composed and sang this chant Anandamritakarshini,

which means “rain of nectar”. Within minutes it started to

rain copiously and the lives of many people were saved.

Le compositeur Muthuswami Dikshtar (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècle)

voyagea un jour dans une région désertique pour rencontrer une

population se consumant de soif et de faim. Il composa et chanta ce

chant Anandamritakarshini qui signifie « pluie de nectar ». Au

bout de quelques minutes, il se mit à pleuvoir abondamment et de

nombreuses vies furent sauvées.

8. Entre terre et

ciel —

Baptiste ROMAIN (instrumental)

H.N. Bhaskar, violin

Patri Satish Kumar, mrindangam

Driss Berrada, oud

Dominique Vellard, oud

Baptiste Romain, fiddle

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

This composition has a Cantiga de Santa María as its

starting point, which acts as the melody punctuating a set of melodic

and rhythmic improvisations.

Cette composition, construite à partir d’une Cantiga de Santa

María, sert de refrain ponctuant des improvisations mélodiques et

rythmiques

9. Ihesus Cristz —

Guiraut RIQUIER

Dominique Vellard, voice

Baptiste Romain, fiddle

Devout chanson by the troubadour Guiraut Riquier (1230-1300). Riquier,

who was born in Narbonne, was the last great troubadour in the Occitan

language. A poet by training, he spent his life in various courts, in

particular that of Alfonso X El Sabio in Castile.

Chanson pieuse du troubadour Guiraut Riquier (1230-1300).

Riquier est le dernier grand troubadour occitan, originaire de

Narbonne. Poète de métier, il passe sa vie dans diverses cours,

notamment dans celle d’Alphonse X de Castille « le Sage ».

10. Raml el maya —

Arabo-Andalusian repertoire

Nouredinni Tahiri, voice

Driss Berrada, oud

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

From the Arabo-andalusian repertory: this is an extract from a nubah

from the Fes tradition. The origins of the nubah go back to medieval

Spain and consist of a highly-codified repertory: each nubah is

made up of five to ten sections where the vocal lines alternate with

instrumental passages.

Répertoire arabo-andalou : extrait d’une nouba dans la tradition de

Fès. La nouba trouve son origine dans l’Espagne du moyen-âge.

C’est un répertoire très codifié: chaque nouba comprend de 5 à 10

sections où le chant alterne avec les passages instrumentaux.

11. Eppo Varuvaro —

Gopaalakrishna BHAARATIYAAR

Aruna Saïram, voice

H.N. Bhaskar, violin

Patri Satish Kumar, mrindangam

This song, whose text is written in the Tamil language, was composed

nearly two centuries ago by Gopaalakrishna Bhaaratiyaar: it forms part

of the Nandanar ballet, which describes the journey of a poor

and oppressed believer in search of spiritual illumination.

Cette chanson en langue Tamil fut composée par

Gopaalakrishna Bhaaratiyaar il y a près de deux siècles ; elle

fait partie du ballet Nandanar qui décrit le voyage d’un pauvre

dévot opprimé à la recherche de l’illumination spirituelle

12. Por nos Virgen

/ Chamss el achiya —

Alfonso X el Sabio (cantiga) / Arabo-Andalusian repertoire

Dominique Vellard, voice & oud

Nouredinni Tahiri, voice

H.N. Bhaskar, violin

Patri Satish Kumar,

mrindangam Driss Berrada, oud

Baptiste Romain, fiddle

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

Compiled by Alfonso X el Sabio, the collection of Cantigas de Santa

María – of which Por nos Virgen is one –

consists of some 420 songs dedicated to the Virgin Mary and written in

Galego, the Galician language. The chant Chamss el achiya is an

extract from an Arabo-Andalusian nubah – passed on by the

Fassi tradition – in the Maya maqam. An instrumental

composition by Dominique Vellard based on the Por nos Virgen

cantiga brings this dialogue to a conclusion.

Compilé par Alphonse X le Sage, le recueil des Cantigas de Santa

María comprend 420 chansons dédiées à la vierge Marie, écrites sur

des poèmes en langue galicienne. Le chant Chamss el achiya est

extrait d’une nouba arabo-andalouse perpétuée par la tradition

fassi, dans le mode Maya. Une composition instrumentale de

Dominique Vellard sur le mode de la cantiga Por nos Virgen

termine ce dialogue.

13. Shanti / Salam

/ Agnus Dei —

Setumaadhava RAO / Improvisation / Plainchant

Aruna Saïram, voice

Nouredinni Tahiri, voice

Dominique Vellard, voice

H.N. Bhaskar, violin

Patri Satish Kumar, mrindangam

Driss Berrada, oud

Baptiste Romain, fiddle

Keyvan Chemirani, zarb

Shanti: this chant was composed at the time when the Indian

people were struggling for their independence and were following the

precepts of non-violence, as advocated by Gandhi. The custom of singing

it at the end of every concert of classical music soon became

established, the purpose being to encourage a spirit of freedom within

the people.

Salam: this chant is

improvised here upon the text of a prayer.

Agnus Dei (Gregorian plainchant, fourth mode): this chant forms

part of the Ordinary of the Mass in the Christian tradition. Its first

appearance dates back to a 10th century manuscript.

Shanti : C’est au moment où le peuple indien luttait pour son

indépendance, suivant les préceptes de non-violence préconisés par

Gandhi, que ce chant a été composé. S’est instaurée ensuite l’habitude

de le chanter à la fin de chaque concert de musique classique, afin de

stimuler dans la population l’esprit de liberté.

Salam : ce chant est ici

improvisé sur le texte d’une prière.

Agnus Dei (grégorien – 4ème

mode) : ce chant fait partie de l’ordinaire de la messe dans la

tradition chrétienne, il apparaît pour la première fois dans un

manuscrit du 10ème siècle.

‘Trialogue’

“A human being is a vessel that God fashioned for himself,

which he has imbued with his spirit, so that his works

may be perfected in it.” (Hildegard of Bingen)

I. A searching, a meeting…

Since the middle of the 19th century, many musicians

and scholars have been searching for keys to the

understanding of Gregorian chant by investigating

extra-European musical traditions. This too has been

my own approach: to reach out into the source of oral

musical traditions for universal vocal gestures which

permit the transmission of both the spirit and the

emotion of the words through them being sung.

If, in the last hundred years or so, music has shed

a substantial part of its functions, for the man of the

Middle Ages, it served a double purpose: personal as

well as social. As the gateway to the Divinity, as the

way of understanding the perfection of Creation and

of the place of man within that Creation, music has,

at the same time, played a part in man’s integration

within his social environment, so as to form and

shape him, and to entertain him as well. In the majority

of the great mystical traditions, the cantor is the

bearer of a power which passes through him: his

whole art consists in transmitting what he has been

provided with; any affectation on his part is strictly

denied him as it would render his singing invalid or

worthless. Such a form of singing unyoked from the

ego of a singer becomes imbued with its own characteristic

power, one of its principal functions being to

touch our greatest inner depths by breaking our

resistances. And it is in the pursuit of this deep truth

in singing, of its meaning and reason which have lead

to the creation of the repertories in which I am

involved, that it seemed to me important to face other

musical traditions, urging from me extended artistic

demands in order to be able to converse with artists

established in strong and age-old traditions.

After more than 15 years of being involved in the

music of the Middles Ages I had the opportunity of

meeting Aruna Saïram, and of putting together an

initial concert programme with her. We took the

time to seek from within our individual repertories

those pieces which seemed to find an echo in the ear

of the other. Gradually, we were able to establish a

rich musical and human dialogue. This friendship and

sense of agreement between us has since led to some

thirty concerts across Europe, India, Morocco and

Malaysia (as well as a recording for emi, entitled

Sources, released in 1999). Our encounter in 2002 with

the Moroccan singer Noureddine Tahiri inspired a

new programme, which is possessed of a single direction:

the pleasure of dialogue – each tradition, each

religion being enriched by and from listening to that

of the others. Emerging from this has come an underlying

message which is revealed in the final piece on

this recording, that of a peace for all, yearned for by

each one of us.

In order to pursue this wonderful musical and

human adventure, we have wanted those instrumentalists

regularly accompanying us within our respective

traditions to also be involved. With their participation

we can thus draw on those areas of our repertories

which call for more than just “pure-voice

singing”. This also brings out additional artistic connections

and correspondences. So, we have three

instruments providing their own form of melodic

support to the chorus of voices on this recording:

the violin for the Carnatic singing, the oud for the

Arabic music and the fiddle (vièle à archet) for the

medieval traditions. In this coming together of the

three traditions an important level of rhythmic support

is provided by mridangam and zarb.

During the course of a creative residency in

Chambéry in June 2011, each one of us was able to

take the time to suggest pieces capable of communicating

not just on the level of textual content but also

on the modal or rhythmic level. Whether it is a case of

songs of true praise or even the human expression of

love running alongside one dealing with mystical love,

the programme for this recording progresses in a form

similar to the way that our initial encounter took

place: by the progressive implementation of musical

resources – a song initiated by a solo voice is gradually

supplemented by the contribution of its corresponding

melodic instrument, which enrobes it so as to

take it towards another mode of expression, spurring

on, in turn, all the “earthly forces” (here the percussion

instruments act as the earthly foundation of the

chant) or by gathering a momentum which liberates it

from its limitations, from its frontiers.

This recording represents that stage of self-fulfilment

which every musician seeks to reach the most

often possible in his or her career, it is the witness of

true agreement and understanding by way of music

and, in the process, a bearer of a powerful message of

dialogue, of respect and friendship between the three

great traditions which have been brought together

here, as much in a musical as a spiritual way.

DOMINIQUE VELLARD

translation: Mark Wiggins

II. Between earth and heaven...

Benedicam Dominum in omni tempore: semper laus eius in

ore meo. “I will praise the Lord at all times: his praise

shall always be in my mouth.” In ore meo... The Latin

word os (which refers to the ‘mouth’ in one of this

extended fraternal series of chants) merits being contemplated,

being reflected upon: to its natural monosyllabic

simplicity comes the further advantage that

its single vowel takes exactly the shape of what it is

denoting in reality. And if your hearing is as sharp as

your vision, you will soon hear forming a sound

group, which involves the French words oral, orée and

aurore. Only the two first words are really similar, but,

no matter. Still, it remains true that these three particular

words take us directly in the midst of the

event – indeed, of the wonder – which this present

recording is supplying us with evidence. In the most

intimate way it establishes for us the belief that the

common future of humanity can be constantly constructed

and reconstructed by the use of bare voices.

Indeed, the voices called together here bring us one

by one towards this shared place of humanity where

the oral character, both restrained and yet liberated,

is reminiscent of those starting points, as reflected

on the French words orée and aurore (beginning and

dawn). When a human being opens his mouth in

truth, he or she immediately is opening up the shutters

of the world. So, what we are being provided

with here to hear makes wonderful sense and also

suggests that the notion of better days lying ahead is

not illusory.

This programme represents a celebration where

the voices are as guests at a banquet. As listeners we

are in a position to hear all the happiness that these

performers have of meeting together like this; like a

gathering of the wise with each one of them pitting

him or herself against the others, yet with no preconception

of anyone trying to gain undue influence or

control; of, if one might say, entertaining each other

(blame the music, after all!) yet all within an atmosphere

of mutual esteem. Here, one is dealing in joy, at

a high level where each voice, each performer acts as

the cupbearer for his or her companion. Among

other things, these fellow guests at the table each

contributing to a state of unanimity through drawing

the mutual offering from their own respective heritages

(the most deeply-rooted offering on earth and

in heaven all in one place) serve to make a place that

is good to live in – and you catch a glimpse that a better

way of living together is possible. Something that

is so noticeable from this vocal suite is its immense

clarity. Undoubtedly it is this lucidity, this form of

nakedness, which immediately convinces us. Yet we

are also disorientated by it, so saturated have we

become by modes of oral character, which are devalued

and stripped of their original nobility. It is not a

matter of where the individual performer comes

from, nor of which tradition he or she may represent,

each of them taking part in this “conversation” acts

precisely in the same way: the first human being on

the first day, the first voice.

The chants brilliantly displayed represent so

many Beatitudes pronounced on those thirsting for

justice, on the meek or on the peacemakers; these

chants represent so many invitations to prayer,

prayer itself undoubtedly having been mankind’s very

first utterance. In each of the chants here – from each

of the voices – it is the same story which comes forth,

the same beginning and the same endeavour. Yet, in

each case there is an answering silence, which

advances the chant’s cause, spreading it out and following

on from it. In each case it is the same innate

humanity which declares itself and takes a stand.

Throughout, one can detect the same transcendental

importance appearing, even if the idioms which represent

that importance (or rather those idioms which

illumine it with great respect) remain impossible for

us to understand – albeit provisionally, deep down!

What we can experience here in these chants is that

one voice rises up, imposes itself, making sure of a

foundation which is both resilient and flexible, rather

as though a walker was supporting it: that foundation

becomes, in the most concrete sense of the term, a

kind of “firmament”, firmamentum in Latin – or, to

put it another way, an inner sky, yet one which is consequently

solid and favourable towards making many

more such daring excursions.

The itinerary which each voice maps out

through using its appropriate scale of sounds seems

also to find expression in the visual register, albeit in

a gradual way: we see the voice, and then we see an

entire landscape being unfurled by the voice – constructed,

in fact, by it! The voice experiments, it

takes risks and chances, it interrogates, but does all

this with an agility which allows one to assume that

the voice has previously passed many times by the

route which it is currently taking. With the support

and foundation now well-assured, the voice tests and

tries out the mountains, dazzling for the sake of it –

like a bird blest with a broad wingspan – by the

almost horizontal vibration of its feathers. The voice

bursts forth, exploring ravines, sudden canyons, and

regions of great shadow, the voice, too, is exposed to

the vast sun: the entire surface of the world rises up

at the whim of – and is devised by – her movements.

From her onward progress springs even he who determines

with a supreme freedom. It reaches the level

beyond reasoning and thanks to the flesh which is

summoned complete by her utterance, the unadorned

voice demonstrates the existence of the Altitude

which it is reaching. At one and the same time the

voice is touching both the ground and the sky: this is

because the singer is strongly installed on the most

intimate “firmament”, in order that he or she can register

– sound is light – the free and unconstrained

heading of mankind towards an all-surpassing “You”.

In a moment which is the very first in its universal

history and which each specific act of singing restates

and renews (it is that, incidentally, which makes it so

moving), mankind only has his voice, is possessed

only of the instinct of his voice with which to

approach his Maker: heading straight towards the

Living force, albeit by way of innumerable detours,

the voice, in its simplicity, acts as a kind of blade. It is

indeed a Golden Age (while always remaining attainable)

when man has no better means at his disposal

than his voice! If there is something of the sacred on

this particular occasion, it should not be understood

as comprising something additional; the sacred

already exists complete there in the posture of the

vocal act itself and in the manner by which the vocal

act approaches and addresses the Invisible, such as

with the ancient text which it is employing.

Everything that one hears here makes beautiful

sense. One thinks of Rilke’s words, in one of his

Sonette an Orpheus: “Over what passes and what

changes, ever wider and ever higher, your opening

song remains and endures!... Alone on earth does

song celebrate and consecrate.”

The human being demonstrates his basic condition

of acting as a minstrel at the point where his

voice is provided with the use of additional instrumental

support (which sometimes assumes here, and

lengthily so, the leading role), or to put it another

way, of being a child. There is nothing more earnestly

childlike than rhythm: the hand which transmits it

and which marks and beats it is as supreme as the

voice. Mankind’s great religious traditions turn out to

be startlingly permeable to each other with the rapid

succession of the most original modalities and the

most compelling and exuberant musical intervals

here: they hear each other, they are in agreement

with each other, without, for all that, clashing. Here,

it is the musical scales which provide the set of rules

for the game which is being carried out. They act as

passwords which the partners of this symphony of

humanity catch in mid-air as though they had been

acquainted with them for a long time, their songs

alluding to each other in order to locate the sign of

peace – in order to offer it to us. For, deep down, it is

the same divine Name – Father and Mother together

– which the mystical poems from Islam, from

India and from the Christian West are caressing by

means of varied and changing images and invocations,

it is by the same Lady-Beauty that they are

charmed, it is by the same burning quest for love that

they entertain us. Whether they come from far back

in time or almost from today, the yearnings and longings,

which they utter, bear witness to a deeply-moving

continuity. Woven out of original texts from the

furthest reaches of the world, and doing so in an

increasingly restricted way as it heads towards its resolution,

the universal cantilena draws up a grand treatise

on peace. This leads one to the conclusion that

the voice, in the exultation and the learned innocence

of its gesture, is rightly the central idea of a

future banquet and the forerunner of a civilization

from which none will be excluded. In view of a world

which struggles to create a unity and which sometimes

even takes advantage of transcendence in order

to legitimize the most reckless acts of violence, the

moment of respite presented here shows us from

which direction is to be found our life-span.

FRANÇOIS CASSINGENA-TREVEDY OSB

translation: Mark Wiggins