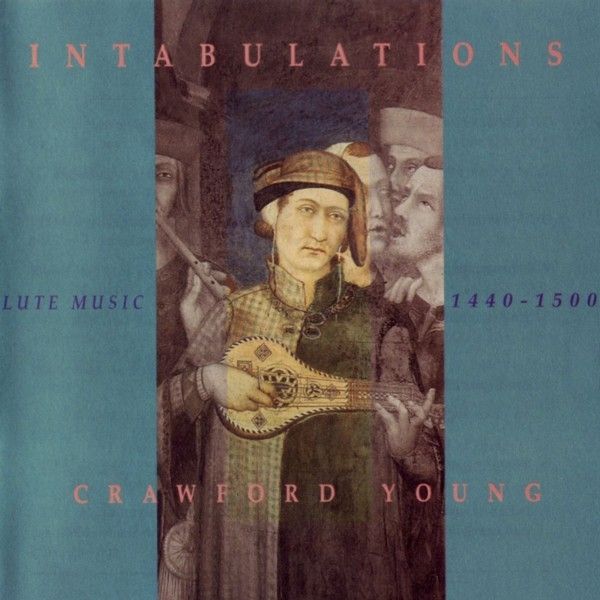

Intabulations / Crawford Young

Lute Music • 1440 - 1500

medieval.org

Lantefana CD 94101

1995

1. La belle et la gente rose [3:18]

Anonymous (ca. 1415) — Turin, Bibl. Nac., Ms. J.ii.9

2. Et videar invidorum [3:50]

Ugolino d'ORVIETO (ca. 1380=1457) — Rome, Bibl. Casanatense, Ms. c ii, 3

3. Ile fantazies de Joskin [2:43]

JOSQUIN (ca. 1480) — Rome, Bibl. Casanatense, Ms. 2856

4. Scaramella fa la galle [2:37]

Loyset COMPÈRE (ca. 1445-1518) / C. Young — Florence, Bil. del Conservatorio, Ms. 2439

5. Textless ballade [2:25]

Walter FRYE (?) (ca. 1460) — Prague, Pamatník Narodního Písemnictví, Strahovska Knihovna, Ms. D.G. iv. 47

6. Tandernacken [1:32]

Crawford YOUNG

7. Va-t'en regrets [2:00]

Loyset COMPÈRE (ca. 1445-1518) — Brussels, Bibl. royal, Ms. 228

8. Amour en un beau vergier [3:30]

Anonymous (ca. 1415) — Turin, Bibl. Nac., Ms. J.ii.9

9. Bekenne myn klag, pulcherissima de virgine [1:57]

Anonymous (ca. 1460) — Munich, Bayrische Staatsbibliothek, Mus. ms. 3725

10. Mit ganczem willen wünsch ich dir [3:44]

Anonymous (ca. 1450-55) — Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Mus. ms. 40613

11. Ballo Verçeppe [4:17]

Domenico de PIACENZA (before 1455) — Paris, Bibl. Nat., fons. ital. 972

12. Wann ich betracht die Vasenacht [3:16]

Anonymous (ca. 1460) — Munich, Bayrische Staatsbibliothek, Mus. ms. 3725

13. Le serviteur hault guerdonné [3:45]

Anonymous (1509) — Perugia, Bibl. Comunale Augusta, Ms. 1013

14. Tandernack [3:16]

Antoine BRUMEL (ca. 1460-ca. 1515) — Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Ms. 18810

15. Cecus non judicat de coloribus [6:10]

Alexander AGRICOLA (ca. 1446-1506) — Segovia, Archivo Capitular de la Catedral, Ms. without shelf mark

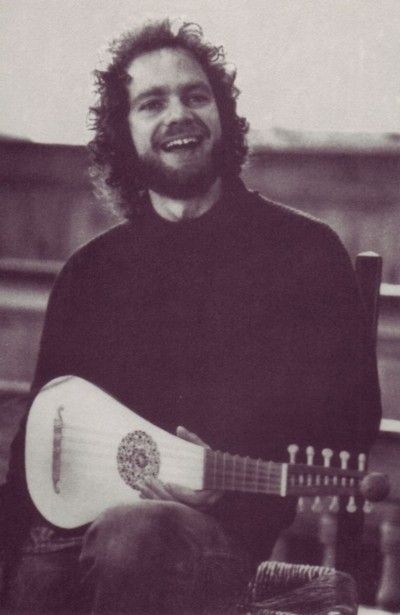

Crawford Young — lute

Michael Craddock — lute

Shira Kammen — vielle

Ralf Mattes — hackbrett

Recorded at Römisch-Katholische Kirche Seewen (CH),

and the Music Room, Cambridge, Mass. (1993)

Engineer: Joel Gordon

Editing: Joel Gordon, Götz Bürki

All arrangements by Crawford Young

Front cover: St. Martin's Investiture by Simone Martini, Basilica S. Francesco, Assisi

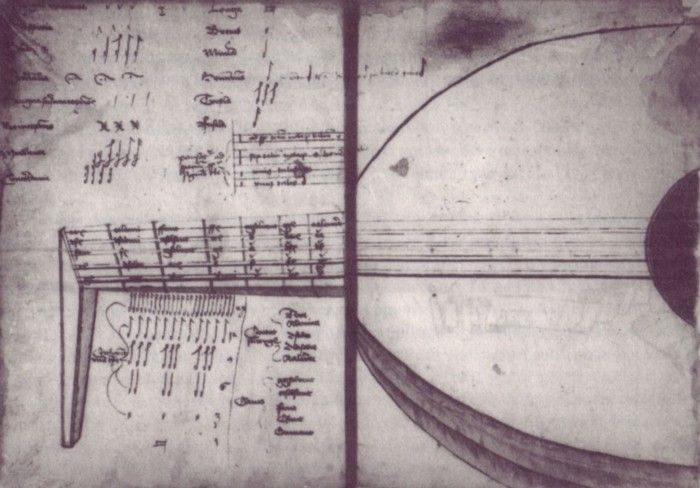

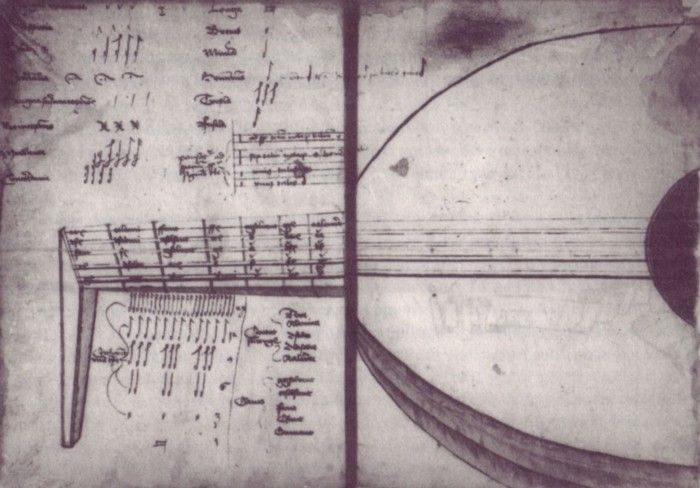

Page 16: from 2° Ms. math. 31, Murhardsche Bibliothek, Kassel

Back: photo by Bob Shamis

Special thanks to Stefan, Joel, Shira, Michael, Götz and Ralf

Instruments:

5 -course lute in g / Joel van Lennep 1982

6 -course lute in e / Joel van Lennep 1993

6 -course lute in a / Richard Earle 1992

6 -course lute in g / Lawrence Brown 1989

6 -course lute in e / Daniel Larsen 1989

vielle / Fabrizio Reginato 1984

hackbrett after Virdung / Nicholas Blanton 1985

© Ⓟ 1995 LANTEFANA

Germany

English liner notes

The

Während die Lautenmusik des 16.Jahrhunderts, auch aufgrund unzähliger

Schallplatteneinspielungen, heute allgemein bekannt ist kann man dies

von der Lautenmusik des 15. Jahrhunderts nicht behaupten. In heutigen

Aufführungen mit Musik aus dieser Zeit wird die Laute fast

ausschließlich als Ensembleinstrument verwandt. Der Hauptgrund hierfür

ist sicherlich das Fehlen jeglicher schriftlicher Aufzeichnungen der

Musik für dieses Instrument vor dem Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts. Neben

vielen bildlichen Belegen geben uns schriftliche Dokumente — von der

Erzählung bis zum höfischen Rechnungsbuch — Hinweise darauf, daß wir aus

diesem Mangel an primären Quellen nicht auf das Fehlen eines

Repertoires schliessen dürfen. Die hier vorliegende CD versucht ein

solches mögliches Repertoire zu rekonstruieren. Dabei ist der Titel ‘Intabulations’

durchaus programmatisch zu verstehen, handelt es sich doch bei solchen

um eine der Hauptformen der Lautenmusik des 16. Jahrhunderts. Die

vorliegende Aufnahme versucht, die um die Jahrhundertwende relativ

unvermittelt auftretenden Traditionsstränge über die Grenzen der

Schriftlichkeit hinweg zurückzuverfolgen um einen Einblick zu geben in

die Musik, die von den berühmten Lautenisten des 15. Jahrhunderts

gespielt wurde.

Die Laute erfuhr im 15. Jahrhundert mehrere

wesentliche bau- und spieltechnische Veränderungen. Einerseits erhielt

das Instrument Anfang des Jahrhunderts die schon von kleineren

Zupfinstrumenten bekannten Bünde, zum andererseits entwickelte sich

neben der Spielweise mit dem Plectrum die Fingertechnik, wobei es

wahrscheinlich viele Zwischenformen gab. Es ist wichtig zu betonen, daß

die Plectrumtechnik keinesfalls nur einstimmiges Spiel zuließ, vielmehr

kann auch mit dem dem Plectrum ein polyphoner Satz klar dargestellt

werden, auch wenn dies in der heutigen Literatur häufig verkannt wird.

Wer

spielte nun im 15. Jhd. Laute? In erster Linie waren dies sicherlich

professionelle Spielleute, wobei man sich jedoch vom romantisch

geprägten Bild des illiteraten, fahrenden Musikers lösen muß. Die ‘Menestrells’

von denen hier die Rede ist gehörten zu einer Gruppe von Musikern denen

es im Laufe des 14. Jhd. gelang, sich in Bruderschafen zu organisieren

und somit einen Platz in der mittelalterlichen Ständegesellschaft zu

finden. Als Städter besaßen sie durchaus Schreib- und Lesekenntnisse,

und schon die frühesten Aufzeichnungen instrumentaler Musik zeigen

grundlegende Kenntnisse der vokalen Satztechnik. Wie wir aus vorhandenen

Dokumenten wissen beherrschten viele dieser Musiker mehr als ein

Instrument. Der berühmte Organist Konrad Paumann wurde auch für sein

Können auf der Laute gepriesen, und neuentdeckte Quellen lassen auf eine

enge Verbindung zwischen dem Repertoire für Laute und dem für Orgel

schliessen. Auch ist von einigen Komponisten des frühen 15. Jhd.

bekannt, daß sie auch als Instrumentalisten tätig waren, so z.Bsp. Baude

Cordier, Jacob Senleches und Rodriguet de la guitarra. Neben diesen

professionellen Musikern finden sich im Lauf des Jahrhunderts mehr und

mehr Belege häuslichen Musizierens, welches dann im frühen

16.Jahrhundert zu den didaktischen Veröffentlichungen Virdungs,

Jundenkünigs und anderer führte.

Die Stücke dieser Aufnahme

versuchen, einen repräsentativen Querschnitt durch die Lautenmusik des

15. Jhd. zu geben. Ein Schwerpunkt liegt hierbei auf den sogenannten ‘Intabulierungen’, d.h. instrumentalen Bearbeitungen vokaler Vorlagen. Das Wort intabulieren

bezieht sich auf den Vorgang des Arrangierens mehrerer Stimmen in einem

großen Notensystem. Durch einen glücklichen Zufall besitzen wir eine

solche Tabula eines Stückes von Guillame DuFay. Dies ist jedoch

nur der erste Schritt der Bearbeitung; Je nach Stil und technischen

Fähigkeiten des Intabulators konnte noch in einer oder mehreren Stimmen

Verzierungen hinzutreten oder aber freie Zwischenspiele, sogenannte Pausae eingefügt werden. Über diese Techniken sind wir — nicht zuletzt durch Konrad Paumannns umfangreiches ‘Fundamendum Organisandi’

— recht gut informiert. Eine andere Möglichkeit bestand darin, nur eine

Stimme der Vokalkomposition zu übernehmen. Gegen diese, meist den Tenor,

wurde dann eine oder zwei kunstvolle Stimmen gesetzt. Diese Technik der

Bearbeitung lässt sich auf zwei Traditionen zurückführen, einerseits

der Improvisation ‘super Librum’,

d.h. der Improvisation über einen gegebenen (liturgischen) Tenor,

andererseits auf die improvisierte Ausführung der ‘Basse Danse’.

Eine solche Satztechnik wurde auch von Tinctoris in seinen Schriften

über musikalische Proportionen gelehrt. Gegen einen in langsamen

Notenwerten fortschreitende, vorgegebene Stimme spielt die zweite einen

Kontrapunkt, der die möglichen Proportionen, d.h. die rhythmischen

Verhältnisse zweier Stimmen, durchläuft. Hierbei handelt es sich, im

Gegensatz zu den zum Tanzen bestimmten Basse Danse um ‘absolute’, d.h. nicht funktional gebunden Musik.

Aus

kompositorischen Überlegungen heraus sind die Stücke des frühen 15.

Jahrhunderts weniger ‘wörtliche’ Übertragungen als die meisten

Bearbeitungen späterer Stücke. ‘La belle e la gente rose’ aus dem

Manuskript Turin enthält ein freies Zwischenspiel, welches sich

stilistisch an das zeitgleiche Manuskript Faenza, das instrumentale

Bearbeitungen vokaler Vorlagen enthält, anlehnt. ‘Et videar invidorum’

ist eine Vokalkomposition Ugolinos d'Orvietos die die

Proportionskompositionen Tinctoris vorwegnimmt. Hier wie in ‘Le serviteur hault guerdonné’ spielt die Laute einen melodisch und rhythmisch komplexen Kontrapunkt gegen die vorgegebene Stimme. Diese ist in ‘Et videar invidorum’ der Tenor, in ‘Le serviteur’ der Superius des ursprünglichen Vokalwerks.

Man

kann davon ausgehen, daß die Lautenisten des 15. Jhd., wie ihre

Nachfolger in spätere Zeit, gerne besonders populäre Stücke als Vorlagen

auswählten, und so folgen, wie in der Vokalmusik, auf die Balladen des

Jahrhundertanfangs sehr bald Rondeaux. ‘Scaramella’ ist ein

typisches Beispiel für ein weitverbreitete Melodie — nicht nur liegt es

in mehreren vokalen Fassungen vor, welche wiederum im 16. Jhd. für Laute

intabuliert wurden, wir wissen auch, daß der berühmte Hoflautenist am

Hof des Borso d'Este in Ferrara, Pietrobono del Chitarino, zumindest

zwei Fassungen dieses Stückes in seinem Repertoire hatte. Leider sind

uns seine Bearbeitungen nicht überliefert, vielleicht auch, weil er, wie

wir aus einem Brief seines Schülers Don Acteon schliessen dürfen, nicht

all seine Kunst weitergeben wollte.

Ganz anders ist die

Situation bei den Stücken aus deutschen Orgelquellen. Hier liegt uns ein

großes Repertoire aus dem Umfeld Konrad Paumanns vor. Für uns von

besonderem Interesse ist Paumanns didaktisches Werk, das ‘Fundamentum Organisandi’,

aus dem wir erfahren, wie ein deutscher Organist im 15. Jhd. Vorlagen

bearbeitete. Hierbei konnte er entweder das Original übernehmen und

auszieren, oder den Tenor der Komposition mit neuen Gegenstimmen

versehen, sowie Zwischen— und Nachspiele einfügen. Da Paumann, wie die

meisten seiner Kollegen, mehrere Instrumente beherrschte können wir

davon ausgehen, daß vieles aus dieser Unterweisung auch für die Laute

Gültigkeit hat.

Aus den späten 15. Jhd. stammen unsere frühsten

Quellen für instrumentale Ensemblemusik. Das Josquin de Prez

zugeschriebene Stück ‘Ile fantazies...’ ist nur in einer Quelle

überliefert, der Handschrift Casanatense. Zwar dürfen wir allein aus der

Textlosigkeit der Komposition nicht auf instrumentale Ausführung

schliessen, aber die Geschicht der Handschrift sowie besondere

Rücksichtnahme auf instrumentale Gegebenheiten wie z.Bsp. einen

beschränkten Ambitus sind deutliche Indizien dafür, daß dieses

Manuskript im Gebrauch eines Instrumentalensembles war.

Agricola's ‘Cecus non judicat de coloribus’

ist zwar in einer späten deutschen Quelle mit lateinischen Text

unterlegt, jedoch zeigt das Werk eine voll ausgeprägte Sprache

instrumentaler Ensemblekomposition. An Dichte der kleinmotivischen

Arbeit, Hoqueti sowie rhythmisch—melodischen Interaktionen ist es kaum

zu überbieten. Ähnliche Kompositionstechniken finden sich auch in den

beiden ‘Tandernacken’, wenn auch, der Natur der Basse Danse

entsprechend, weniger dicht. Ob zu diesen Stücken noch getanzt wurde,

oder ob sich hier die Form absolutiert hat lässt sich heute nur schwer

sagen, sicher ist jedenfalls, daß der Tenor, eine bekannte Liedweise,

notengetreu übernommen wurde und das Stück somit tanzbar ist.

Neben

diesen langsamen Schreittänzen gab es natürlich auch andere, schnellere

und rhythmisch abwechslungsreichere Tänze. In Italien entwickelte sich

der Ballo, eine Abfolge unterschiedlicher Tänze mit wechselndem

Grundschlag. Zu dieser Frühform der Tanzsuite existieren ausführliche

Choreographien, die uns noch heute Einblick geben in die Welt höfischer

Musikpflege, aus der wir hier einen Ausschnitt zeigen wollten.

RALF MATTES

Compared to sixteenth-century lute music, 15th century repertoire for

solo lute is relatively unknown. Indeed, in today's performances of 15th

century music, the lute is used almost exclusively as an ensemble

instrument. Perhaps the main reason for this is our lack of notated solo

music for the instrument before the end of the fifteenth century.

However, there are strong indications that the lack of primary sources

of lute music by no means suggests that the instrument had no repertoire

before 1500, a position which is supported by many works of the visual

arts as well as written documents — from narratives to archival records.

The present recording tries to reconstruct such a possible repertory,

its title ‘Intabulations’ referring to one of the main genres of

sixteenth-century lute music. Using as its starting point the sources

which rather abruptly appear at the beginning of the sixteenth century,

the program attempts to trace back certain musical traditions which must

have existed longer than it would appear from these surviving

manuscripts.

During the fifteenth century the lute experienced

major changes in its construction and playing technique. One development

was the addition of frets, which were already in use on smaller members

of the plucked-instrument family; a second change was the gradual shift

from plectrum to finger technique. It is important to emphasize that

plectrum technique, contrary to often-encountered modern commentary, in

no way restricts a performer to single-line playing, and we can safely

assume that polyphony was part of the 15th century lute player's

repertory.

Who, then, played the instrument in the fifteenth

century? First and foremost, lute players were professional minstrels

who were not the illiterate wanderers of romantic lore. These musicians

belonged to a class of artists who, in the fourteenth century, organized

themselves into fraternities, and thus were able to establish their

place in the structure of society. As educated members of society they

were literate, and the earliest surviving traces of their works already

show a basic knowledge of the rules of polyphonic composition. We know

from archival documents that such musicians had often mastered more than

one instrument. The famous blind organist Konrad Paumann was equally

well-known for his lute playing as for his keyboard skills, and further,

recently discovered documents suggest a close connection between the

repertories of organ and lute. We also know composers of vocal music

from the late 14th century, such as Baude Cordier, Jacob Senleches and

Rodriguet de la guitarra who also worked as instrumentalists. In

addition, private music making became more and more popular during the

fifteenth century, which ultimately led to the early sixteenth century

didactical prints by Virdung and Judenkunig among others.

The collection of pieces presented here represents a cross section of fifteenth-century lute repertory, with an emphasis on intabulations, in other words, instrumental arrangements of polyphonic vocal music. The term ‘intabulation’

refers to the actual writing down of the individual voices of a

composition onto one musical staff. We have an interesting example of an

early step in the arranging process in the intabulation of a Dufay chanson

in a manuscript now in Vienna. Depending on the style and technical

abilities of the arranger, free interludes — so-called ‘pausae’ — could

be added, as well as ornamentation in one or more voices . Thanks to

Konrad Paumann's ‘Fundamentum organisandi’, a thoroughly complete

instructional work on the art of extempore playing, we know more than a

little about how to make such additions; his existing compositions also

are excellent models which finely illustrate the art of making intabulations.

Another

way to realize a vocal piece instrumentally was to take only one voice

of the original polyphonic song, normally the tenor, against which one

or two new parts were composed. This arrangement technique has its roots

in two different traditions, one being the church music tradition of

singing ‘super librum’ upon a given cantus firmus, and the other being the extempore melodic playing which was a feature of courtly dance music such as the ‘bassadanza’.

Such a compositional technique was also described by Tinctoris in his

writings on musical proportions. Against a slow-moving, pre-given voice

the second part creates artful counterpoint which features dense

rhythmic variety in the dialog of the two voices. Such music could be

described as early ‘chamber music’, that is, without a specific

function like dance accompaniment, signal sound or liturgical/political

function, rather as abstract music for the intellectual enjoyment first

of the player and secondly of the listener.

Because of

compositional considerations, the solo intabulations of vocal music from

the early fifteenth century clearly demonstrate a less literal

technique of arranging than most of the later pieces. ‘La belle et la gente rose’,

from the Turin manuscript, includes a free interlude melodically

reminiscent of the style of the Faenza Codex, a contemporary collection

of instrumental pieces based on vocal models. ‘Et videar invidorum’

is a vocal composition of Ugolino d'Orvieto which reminds the listener

of Tinctoris' later proportional works. In both this piece and ‘Le serviteur hault guerdonné’, the lute plays a melodically and rhythmically complex voice against a simpler second voice. In ‘Et videar invidorum’ this second part is the tenor, whereas in ‘Le serviteur’ it is the superius voice of the original vocal composition.

One

can assume that fifteenth-century lutenists, like their later

counterparts, especially liked to use popular songs as models upon which

they based new arrangements. In vocal music and thus in intabulations,

the later fifteenth-century rondeau replaced the earlier ballade as the

preferred song form. ‘Scaramella’ is a typical example of a

widely distributed melody, which served as the basis for a number of

vocal compositions which, in turn, were intabulated for solo lute in the

sixteenth century. We know that a famous lute player at the Este court

in Ferrara, Pietrobono del chitarrino, had at least two arrangements of

this melody in his repertoire. Unfortunately these arrangements

themselves do not survive, possibly because of a reluctance on the

lutenist's part (as reported in a letter written by his student Don

Acteon) to give away his art.

The situation is different,

however, with the pieces from German organ sources; here we have a

large, preserved repertoire from the circle of Konrad Paumann. Of

special interest today is Paumann's didactical work, the ‘Fundamentum organisandi’.

From this one can see how German organists of the fifteenth century

arranged vocal compositions. The organist either took the original and

added ornaments, or he used the original tenor part as a basis for

composing new parts around it, as well as adding interludes and

postludes. Because Paumann is known to have been a virtuoso lutenist as

well as organist, we can assume that much of the information from the ‘Fundamentum’ applies also to the lute.

From the late fifteenth century come the earliest sources for

instrumental ensemble music. One piece from this repertory, the ‘fantazies de joskin’,

is found only in the Casanatense Chansonnier, a manuscript which we

think contains instrumental ensemble music, not only because the pieces

lack text, but also because of the history of the manuscript and the

restricted range of the voices.

Although Agricola's ‘Cecus non judicat de coloribus’

is found in a late German source with a Latin text, it displays a fully

developed language of instrumental composition. In terms of the density

of short motives, hockets, and rhythmic-melodic interaction,

this work hardly finds an equal within the body of contemporary

compositions; similar compositional techniques are found in the basse danse- related ‘Tandernacken’,

albeit used less densely. It is difficult to say today whether these

pieces provided accompaniment for the dance, but they are ‘danceable’ in

the sense that the original tenor melody is intact. In addition to the

more reserved basse danse there were, of course, other dances, including the faster Italian ballo,

which characteristically used four different rhythms corresponding to

four different kinds of steps. Choreographies of these dances still

survive, and they help to give us a glimpse of the courtly music world

of the late Middle Ages, a musical world which the present recording

seeks to suggest.

Transl. CRAWFORD YOUNG