MORTIKA

The word 'mórtis' in Greek underworld slang refers to a person

who is both tough and elegant, as it were the cool bearer of knife and

suit, a counterpart to the 'apache' of Paris. Mórtika simply

means songs about male 'mórtes' and female 'mórtisses'. (See

also glossary below). This CD holds a collection of urban songs and

instrumentals centred on this theme, recorded commercially between 1927

and 1946 by Greek musicians in Greece, Germany and the USA. (Track

16, undateable, and track 21, privately recorded in 2000, are

exceptions.) All, in conventional terminology, might be considered

as belonging to the 'rembetica' genre, but we who have compiled and

produced this record would rather see them emancipated from the

straightjacket of genre categorisation. Apart from the intrinsic,

moving musical quality of the performances, this compilation is

distinguished by the rarity, and often excellent condition of the

originals, and by the quality of Ted Kendall's remastering.

Listening through Mórtika, you will make the

acquaintance of some of the central figures of the period, both

instrumentalists, singers and songwriters, and become familiar with

some of their variety of vocal styles and techniques, their idiomatic

use of various plucked, hammered and bowed string instruments, and the

accordion, and also with their song lyrics, which treat of typical

'underworld' themes such as drugs, love, theft, murder, prison, and

having a good time. All this music is associated, one way or another,

with subcultures of outsiders, whether at home or in imposed or

self-chosen exile, and whether they represent the urban musical culture

of Asia Minor and Istanbul/Constantinople, the local tradition of

Piraeus subcultural music, or the Greek musical culture of the

Greek-American population.

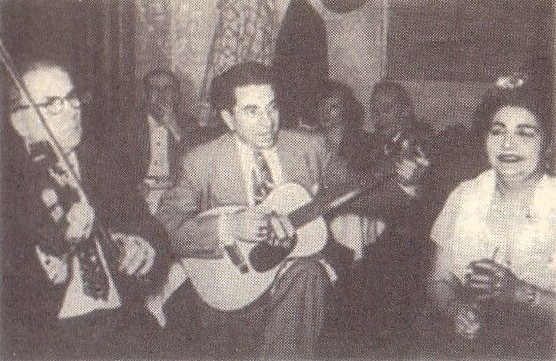

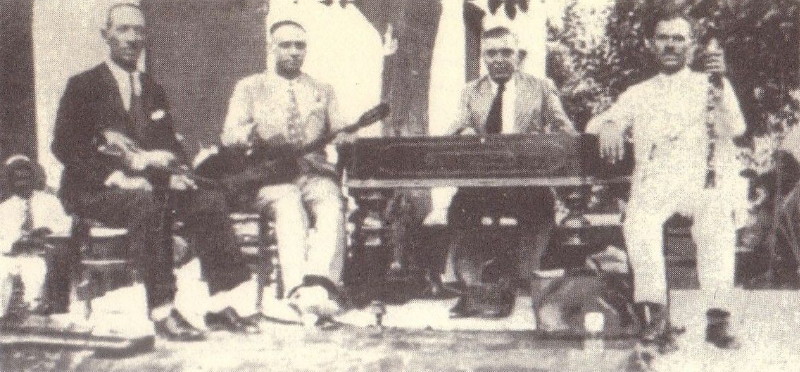

You will hear the pioneer Greek-American bouzouki player Ioánnis

Halikiás (aka Jack Gregory), the pioneer of Piraeus

rembetica Márkos Vamvakáris, the great singers of

Asia Minor origin Ríta Abadzí and Andónis

Dalgás, the singers Maríka Papagíka, Stellákis

Perpiniádhis and Kóstas Roúkounas, and

two of the handful of recorded guitar-playing Greek songsters of the

period, Yiórgios Katsarós and 'Kostís',

based in the USA and Athens respectively. Furthermore, you will hear a

very early recording by Dhimítris Góngos

'Bayiandéras'. Here is one of the only two known recordings

by the bouzouki player known as Manétas, cited by both Márkos

Vamvakáris and Stelios Keromítis as one of

the seminal figures of the Piraeus bouzouki of the 1920s and

responsible for what became the standard DAD tuning of the three-course

bouzouki. The major recording artist on the accordion of this period, 'Amirális'

Papadzís, is here, and one of the only two known sides

recorded by a little known bouzouki player and singer called Zouridhákis.

The composer S. Gavalás is the featured vocalist on a

virtually unknown, incredibly well preserved recording. On many tracks

you will hear one of the studio eminences of the period, Spýros

Peristéris, playing mandolin, mandola, guitar and bouzouki.

The collection is rounded off by a contemporary recording by musicians

who sing and play as though time stood still, independently of the

whole 'rembetica revival' phenomenon of the past few decades.

These notes, eschewing repetition, hope rather to add new perspectives

to previous writing (see bibliography & discography) on

various aspects of the recorded urban Greek music of this period.

On

recorded music

In 1878, Thomas Edison established the Edison Speaking Phonograph

Company to sell the new machine which he had invented during the

previous year. Before this, printed music, musical instruments, music

lessons, and the opportunity to listen to living musicians in real

time, had been the only musical commodities. The invention of sound

recording created a new commodity, and triggered a novel industry - the

manufacture and sale of petrified sounds. The recording industry -

likewise the owner of the means of production and distribution - has

since then immortalised sounds considered, and often proved, saleable.

That music could be recorded and distributed autonomously by virtually

anyone, was unthinkable until the digital and Internet revolutions

placed the means within the reach of millions.

Thus the obvious but easily overlooked fact that the legacy of

commercially recorded music is no more than a document of the choices

and successes of the recording industry's marketing analyses and value

judgements and not a representative historical document of the music

making of mankind since 1878. Non-commercial field and documentary

recordings represent, likewise, the no less subjective, though often

different, choices of musicologists. Together, these legacies are what

we have. If, for example, a certain kind of music is considered

unsaleable because its public is believed to lack buying power, and

'irrelevant' to ethnomusicologists because it isn't 'true folk music',

then it stands a good chance of not being immortalised on disc.

Early

Greek recordings

Unfortunately the very early Greek recordings have been inaccessible to

this writer, (for one exception see 'guitar' below), which

precludes appraisal of their style and content. Their very existence is

however worthy of brief mention. The first known records of Greek music

were made by tenor Michalis Arachtingi in New York in May 1896,

on the Berliner label. The first recordings from Greece itself

known to this writer were made for documentary purposes on the island

of Lesbos in 1901, by an Austrian researcher (see discography).

The next commercial Greek recordings we know of date from circa 1903;

made in Constantinople, they also appeared in Egypt. Information as to

when the first commercial recordings were made in Greece itself is

unclear. According to Paul Vernon, Odeon may have made large

numbers of recordings in Athens, beginning in 1904, but virtually all

the documentation appears to have been destroyed.

It would appear that the Gramophone Company recorded more than

200 sides in Athens during 1907 and 1909, having previously made Greek

recordings in Egypt. A number of documentary recordings of Greek music

were made in Germany in 1917 by Preussische Phonographische

Kommission. At the time of writing we lack further information on

commercial recordings made in Greece itself before 1952, and there is

sparse documentation on the urban Greek music of the period outside of

the commercial recordings. All this rather 'negative' information

serves to underline how truly difficult it is to delineate the early

history of 'rembética'.

Observations

on rembetica and the genre question

The varieties of music contained in Mórtika have been

known by the blanket term 'rembética' (Greek

'ρεμπέτικα') at least since Ilías

Petrópoulos first published his pioneering book 'Rembétika

Tragoúdhia' in 1968. A certain number of songs were indeed

designated as 'rembétiko' on record labels very early on, but

these were pieces of a mildly erotic or demi-mondaine nature, far

removed from what later came to be designated as rembetica. However, in

all forms of art, genres are nearly always after-the-event

constructions of historians, critics and businessmen, in varying

combinations, and this music is no exception. The word 'rembetis' is

the masculine form of one of several Greek argot terms for persons

embodying various kinds of subcultural attitudes and behaviour whether

it be in terms of dress, drug use, fighting, other criminal activity,

or varying kinds of behaviour valued as 'honourable' within the

culture. In its plural adjectival form 'rembetica' thus came to be used

as a blanket term for a variety of musical styles whose only common

denominator is, in the final analysis, that they have been embraced by

a particular Greek revivalist subculture from the 1970s onwards. Many

will immediately associate to the bouzouki as the emblematic instrument

of this 'rembetica'. Mórtika will dispel this inaccurate

and sweeping notion and impart a more varied perspective.

More

history

Much of mainland and island Greece lived under Ottoman domination for

about four centuries. Crete was still under Ottoman rule as late as

1913. Various Italian city-states were also power factors at various

times. The establishment of the geographical boundaries of Greece as we

know it today was not finalised until 1947, and, of course, the Cyprus

question is still not resolved.

The musical consequences of this are probably still not well

understood. We really can't know of any music which can be said to have

survived in pure Greek form through all those centuries - in fact one

might very well ask: what is pure Greek music? Some Greeks might gladly

lynch me for asserting that. Cultures of subjugated groups in other

parts of the world have certainly used the musical language and tools

of their conquerors and rulers, albeit married to original ethnic

elements, as the examples of blues, jazz, much South American music,

and Hindustani classical music, dearly show.

As citizens of the Ottoman Empire, many ethnically Greek musicians were

members of a cosmopolitan profession. Recognition within Ottoman art

music was accorded of merit, not ethnicity, in spite of the Ottoman

millet system of segregation according to religious affiliation.

Movements and migrations within the various previously or currently

Ottoman dominions meant that, for example, musicians who were

ethnically Armenian, Greek, Gypsy, Jewish, Romanian, or Turkish had a

considerable shared repertoire.

Urban musical culture of Asia Minor during the first decades of the

20th century being thus truly cosmopolitan and 'transethnic', the same

musician could record in both Greek and Turkish although 'ethnically'

neither, and be defined as Greek when suitable. Prominent examples, not

represented on this particular CD, are the singer Róza

Eskenázi, born into a Jewish family in Istanbul, who sang in

both Greek and Turkish, her Armenian-born oud player Agápios

Stamboúlis, (see opposite page) and the oud player 'Marko'

Melkon Alemsherian, also of Armenian parentage. Born in Izmir,

Melkon fled to Greece to avoid conscription in the Turkish army, and

emigrated from there to the USA in the early 1920s, where he recorded

songs in Armenian, Greek and Turkish. The resolution of the

Greek-Turkish conflict of the early 1920s, when the territorial limits

of today's Greece were in large part defined, resulted in the

large-scale relocation of populations on the basis of religion, and

many musicians from urban Asia Minor who had previously functioned in

that cosmopolitan culture found themselves in Greece. They were often

highly competent 'learned' musicians who played instruments not

previously identified as typically 'Greek', for example oud, kanun,

santoúri, and kemençe (called lyra in Greek).

This had great significance for the development of the music on this

record.

Thus, which music which today can be called Greek, and what its 'true'

roots are, are complex questions, which will be answered very

differently according to the perspective of the person asked. Extreme

nationalists, keen on purifying Greek music from vile Turkish and/or

Gypsy contamination, may either dismiss oriental modal forms as

unGreek, or claim that they are of Greek origin (Byzantine or ancient

Greek or both). Orientalists such as Alain Daniélou may

assert close relationships with Indian ragas which - only superficially

or coincidentally - share similar or identical scalar material.

The viewpoint held by the compilers of Mortika is that we are simply

presenting some very good music from outside the conventional

mainstream of Greek popular music, played and sung by people who

probably defined themselves as Greeks even if not born in Greece, and

whose musical roots drew nourishment from the soils of the Greek

mainland, the Aegean islands, Crete, Asia Minor, and the USA.

Drug

themes and rembetica

Themes connected with drug use provided the subject matter for a fair

proportion of the songs recorded during this period, and indeed for

many of the songs on this record. Cannabis is the commonest drug

mentioned, though heroin and cocaine also figure, as do wine and

spirits. Common sub-themes are the search for a drug-dealer, the water

pipe, the 'teké' milieu where 'mánges' smoked hash, and

played and listened to baglamás and bouzouki, fights involving

drug users, and the state of abstinence called 'harmania'. Many

but certainly not all of the significant musicians of the period were

drug users, and one famous figure, Anéstis Deliás, died

very young of a heroin overdose, some years after recording a warning

song about hard drugs.

During the Metaxas regime (1936-1941), censorship of this and other

'subversive' kinds of subject matter, and edicts aimed at eradicating

the Asia Minor oriental style of music, were introduced in Greece.

Censorship was very effective from 1937 to 1941, relaxed for a brief

period after the liberation, and was back in full effect by autumn

1946. From that time on, until the PASOK party came to power in 1981,

songs about drugs were simply absent from the 'official' Greek scene as

though they had never existed, though old recordings, and knowledge of

the repertoire, certainly circulated in private circles. Nowadays the

old recordings are freely reissued in Greece.

One might ask: what was the significance of songs on drug themes

in'rembetica'? Neither romanticising nor idealising drug use at the

time they were composed and recorded, they rather told stories of

everyday life, commanding no particular musical frameworks or stylistic

elements that distinguish them from songs on other typical 'rembetica'

themes of the same period. A reasonable view would be that they

asserted and confirmed the role of drugs, and drug-associated rituals,

in defining aspects of sub-cultural group identity. Which can also be

said about some other typical themes of rembetica.

So what, if anything, is specific about drug themes? Drugs offer an

escape into another sphere of feeling, perceiving and relating, a

respite from life's normal toughness. If we consider that this music

evolved mainly among people who shared experiences of exile, of poverty

and deprivation, of life on the outside of 'society', it is perhaps not

too far-fetched to conjecture that drugs were a sort of comforting

maternal substitute, and that the 'high' was, at least in part, a state

reminiscent of the paradise of early maternal care. So the emphasis on

this in the songs might in turn be seen as a covert hymn to the mother.

THE

INSTRUMENTS

There are some major traps in studying the history of musical

instruments. The same word may denote quite different instruments, and

the same instrument may be known by etymologically quite distinct

names. An instrument that has wandered in time across national and

cultural boundaries, may be 'appropriated' by nationalist apologists in

any of its host countries. Both European and Oriental instrument-making

traditions flourish side by side in Greece, and not one of the

instruments to be heard on this CD - accordion, baglamas, bouzouki,

cello, guitar, mandola, mandolin, laouto, lyra, tsémbalo,

kombolói, violin - can claim exclusively Greek origin as to both

name and form. In the following we have tried to give some detailed

accounts in a manner hitherto not attempted within the scope of CD

booklet notes.

Baglamas

# 21

The diminutive three single- or double-strung plucked baglamas takes

its name from one of the several sizes of the Turkish long-necked lute

known in Turkey today as the 'saz'. It is, of all the instruments

mentioned here, perhaps the most uniquely Greek, and it has also been

the least standardised in size and form. In the early days of this

music it may have been most associated with prisons and hashish. It is

played alone as a melody instrument, with or without vocals, or in

ensembles, where it is both used as a primarily rhythmic instrument,

emphasising pulse or rhythmic structure, and/or as a melody instrument,

either carrying the melody alone or playing in parallel octaves with a

bouzouki.

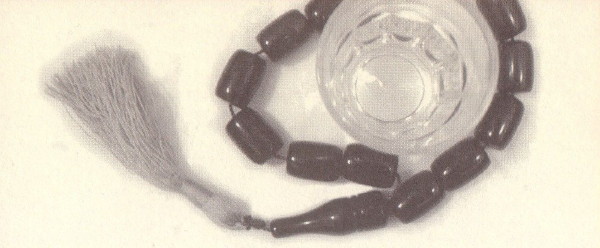

Komboloi

#8, 14

Worry-beads rattled against a drinking glass (see opposite page).

This was characteristic of the music of hash dens, 'tekédes'

i.e. what may reasonably be termed Piraeus rembetica, though it was

also used in some recordings in the Asia Minor style.

Guitar

#1, 2, 4, 5, 7-10, 12-20

The guitar has a fascinating history in Greek popular music. It was

quite certainly played by Greek musicians at the beginning of the last

century. In a recording of a Greek dance tune played on mandolins and

guitar, recorded in Istanbul in 1905, (Instrumental Trio, Vlachiko

Syrto, Victor 63556, 404r, recorded by M.Hampe), the guitar is

heard playing bass notes and chords very much as it might today. During

the period during which the recordings on this CD were made the guitar

was also played in various purely idiomatic Greek fashions both in

Greece and the USA (see tracks 2, 10,13 20). In fact one of the

first responses to the pioneering Halikiás recording of 1932 was

a guitar duet 'cover' by Peristéris, accompanied by Kóstas

Skarvélis, with guitar replacing bouzouki as the solo

instrument. Peristéris appears to have continued using bouzouki

and guitar interchangeably throughout the 1930s. From the 1940s, with

few exceptions, the guitar as a solo voice seems to have disappeared

from the subcultural musical scene, though it continued to be an

important solo instrument in the 'cleaner' light music which eschewed

the bouzouki.

The conventional acoustic wire-strung guitar, played with a plectrum,

or in fingerstyle, has maintained a vital role in Greek popular music

up to the present day. Greek wire-strung guitars are relatively lightly

built with Spanish-style bodies, of different character from the North

American steel-string guitar used by Katsarós. Often the

guitar will be tuned down a whole tone or more; Kostís (see

track 10) Doúsas and Katsaros all used various open

tunings at least some of the time.

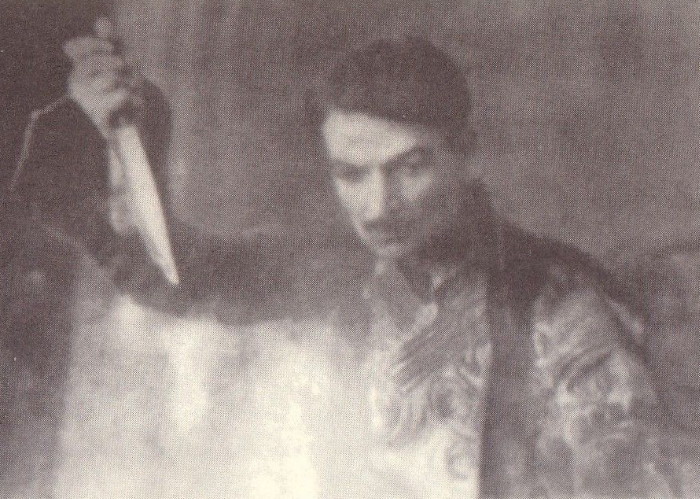

Dalgás is to be seen playing a

nine-string guitar with three bass strings on an extension, in a

photograph from around 1930 (see p5). At the time of writing we have no

further reliable knowledge on the origin and use of such guitars in

Greece, although various 'harp guitars' in Western Europe during the

18th & 19th centuries have been extensively described.

The Hawaiian craze, which swept the world during the first decades of

the 1900s, did not leave Greece untouched, and Kostís appears to

have played Hawaiian style tunes on steel guitar, as well as playing

magnificent 'rembetica' in the style heard here.

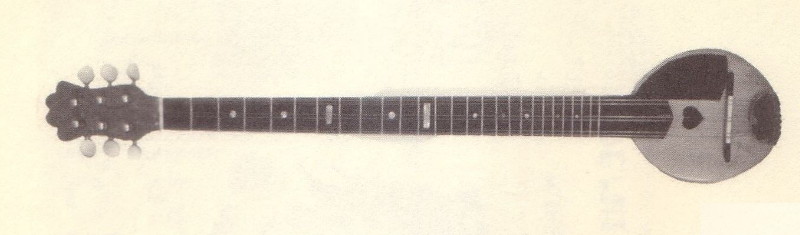

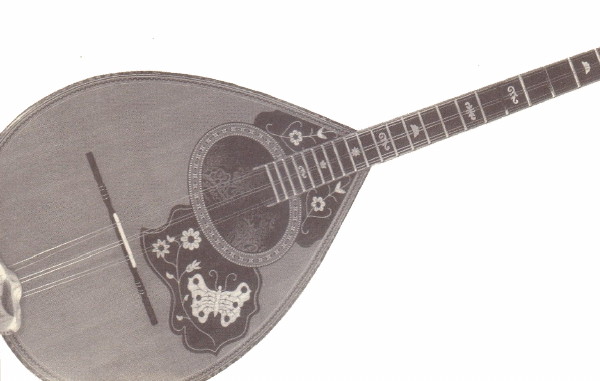

Bouzouki

#1, 3, 4? 5, 7, 8, 14, 16, 18, 21

The bouzouki is a long-necked lute with a wooden soundboard,

carvel-built body and a narrow neck, strung with paired metal strings

and played with a plectrum. Until the mid-fifties it was exclusively a

three-course instrument, i.e. it had three pairs of strings. Its

so-called 'evropïkó' (European) tuning (DAD) was first

standardised during the late 1920s or early 1930s, when ensemble

playing led to the relative abandonment of the handful of

non-transposable tunings called 'douzenia'. The lowest course has

always been an octave pair whereas the other two are unison pairs.

The characteristic tremolo component of mandolin playing seems to have

been imported to the technical arsenal of bouzouki players by the

1930s, especially by Tsitsanis and Chiotis; Vamvakaris

seems to have used tremolo sparingly in his own playing.

Since the mid-fifties, both three- and four-string bouzoukis have

existed side by side, the latter introduced largely on the initiative

of the bouzouki and guitar virtuoso Manólis Chiotis. The

four-string instrument is tuned CFAD with two octave pairs and two

unison pairs. The three-stringed instrument was losing ground until the

'rembetica revival' of the 1970s brought it back into favour with a

younger generation.

The bouzouki has been the subject of much speculation and controversy.

The instrument as we know it today, hitherto perhaps best studied by

the Finnish ethnomusicologist Risto Pekka Pennanen, is perhaps

not much older than the history of sound recording. There is no

consensus on the origin of its name. There is a consensus that a

similar instrument, virtually identical to the instrument known today

as the Turkish saz (Greek 'sazi'), was known earlier on in

Greece as 'tambourás'. But the bouzouki as known since the

beginning of the last century is not much older than just that. It

probably developed simultaneously both in mainland Greece and among

emigré Greeks, and its present-day construction is the result of

a continuous process of development in response to developing needs and

fashions, the first major change being the introduction of the

Neapolitan mandolin-type of body instead of the typically Oriental body

carved out of a single piece of wood. There is, however, evidence that

Turkish saz modified to be playable as bouzoukis were in use in Greece

as late as the 1940's (see Bibliography: Baroúnis).

Furthermore, according to Jack Halikias jr., one of his father's two

surviving bouzoukis maybe of this type.

As in the case of many instruments, use in new contexts created a

demand for greater volume. This spurred luthiers to build higher

tension instruments with different bracing. During the 1950s electric

amplification was also introduced. Fashions of ornamentation have

varied from the simple to the extremely ornate. A point of interest -

some of the earliest surviving bouzoukis which resemble today's

instruments, were built in the first decades of the 1900s in the USA by

the Greek luthier workshop which later changed its name to Epiphone.

The first known recording of a bouzouki, a single side, was made in

Germany in 1917 by Preussische Phonographische Kommission, for

academic purposes. It was never intended for commercial use and is

still, unfortunately, unreleased archive material. The first known

commercial recording including a bouzouki was made in the USA in 1926;

in 1931 the instrument made its recording debut in Greece (see track

3). However, the first truly instrumental solo recording was made

in New York in 1932 (see notes to track 1). Halikias' historic

USA recording may well have triggered the bouzouki's recording career

in Greece; unfortunately, at that time he followed it up with just two

more sides in 1933. As far as we know the bouzouki was then ignored in

American studios from 1933 -1942. the very period of the instrument's

triumphal progress in mainland Greece.

By the 19405 the bouzouki had become the dominant lead instrument in

Greek urban popular music. In the late 1940's Manos Hadjidakis

introduced bouzouki music to the middle classes, followed by Míkis

Theodákis in the late 1950s. From then on the instrument was

enlisted into the nationalist project and the building of the Greek

tourist industry. It was, for example, to be seen decorated with inlays

depicting the Acropolis. The bouzouki was, and still is, to be heard

playing a kind of Greek popular music which Greeks themselves call

'touristiká'. By this is meant music that Greeks assume tourists

wish to hear. To what extent Greeks alone have played an active role

both in creating the genre and the myth of its genuine Greekness is

another question. Parallel with this tourist music however, the

bouzouki continues to play a central role in urban popular music made

by Greeks for Greeks.

There is an instrument played in Lebanon and Syria called 'buzuk' or

'bosuq'. It differs from the Greek bouzouki in only having two pairs of

strings, and in that the frets are arranged according to a quite

different division of the octave than the standard Western chromatic

fretting.

Violin

#4, 11, 19, 20

Already developed to its present-day form in Italy by the 1500s, the

violin has proved itself the most adaptable of all musical instruments,

there being hardly a country in the world which has not adopted it, and

Greece is no exception. The instrument has been a natural member of all

kinds of Greek ensembles, country and urban, subcultural and

mainstream, for at least a century. There were several brilliant

violinists during the period represented by Mortika, for

example the Bulgarian-born Macedonian Slav Nick Doneff (#20), Yiánnis

Dhragátsis aka Ogdhondákis, Dhimítrios

Sémsis aka 'Saloníkios', Aléxis

Zoúmbas, and Athanasíos Makedónias

(#11).

Accordion

#9,17

The accordion was first developed in Vienna in the early 1800s, the

name itself being patented in 1829. Two musicians figure in the early

days of Greek recordings, Yangos Psamatiános and Andónis

Amirális aka Papadzís. Their instrument

sounds drier and has no built-in beat tremolo and is primarily a solo

melodic instrument. Later on, the accordion, as both accompaniment and

melody instrument, was often an integral part of the line-up in

rembetica ensembles from the 1940s onwards.

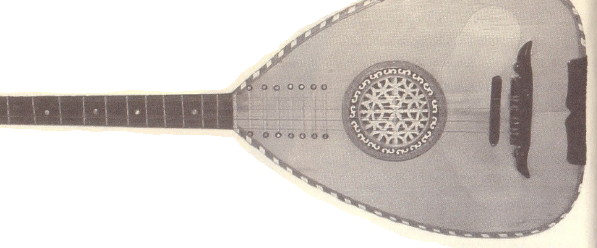

Lauto

#6

The word laoúto, or laghouto, is directly taken from the Italian

word for lute, which in its turn originally came from the Arabic words

'al ud' - the wood. The laouto is a gut- or nylon-fretted four-course

long-necked lute with pared metal strings tuned in fifths. Its

carvel-built body is considerably larger than that of the bouzouki but

it has a shorter neck. It is as it were a hybrid product of the

mandolin and the Oriental oud, a marriage symbolising Italian and

Turkish influence in the area. It is played both melodically and

chordally and has traditionally been an instrument of Crete and the

other Greek islands, and of non-urban mainland Greek folk music.

Lyra

#6

The lyra is a small vertically held bowed instrument of which there are

several known basic types in Greece. In the music on this record we

hear the Cretan version. A lyra indistinguishable from what was called

'kemence' in Turkey was brilliantly, often achingly expressively played

on many recordings of the period by Lámbros Leonarídhis.

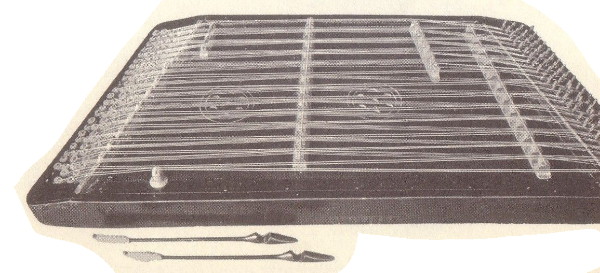

Santour

& Cimbalom

(Greek: tsimbalo) #3, 4, 11, 15

Tsimbalo and santouri are two Greek terms for variants of the type of

instrument known as hammer dulcimer in English, 'cimbalom' in Hungary,

'santur' in Turkey and Iran, 'santir' in Irak and 'santoor' in India.

Current scientific research admits no real evidence that this type of

instrument existed during antiquity. The first convincing depiction is

in a 12th century carved ivory book-cover from Byzantium. Kettlewell,

the instrument's foremost historian, suggests a complex skein of

diffusion routes in Western, Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle

East, and Asia, from about the 12th century onwards, and notes that the

instrument was not mentioned in Middle Eastern sources until the 17th

century, despite certain claims to the contrary.

During the later Ottoman period there was a complex interrelationship

between Armenian, Greek, Gypsy, Jewish, Romanian and Turkish musicians,

all of whom included the dulcimer among the instruments they played.

Information on the history of the instrument in Greece itself is

sparse. The oldest written record of its presence is by the Brit-

ish traveller Edward Daniel Clarke, who heard it in Athens in

1802. It was first mentioned in Smyrna in 1850, as being of western

origin (of the Franks). Cafe songs of Smyrna were often

accompanied by violin and santouri. When refugees from Smyrna and other

parts of Asia Minor came to Greece in the early 1920s, they brought the

instrument with them and it subsequently spread over many parts of the

country. The portable type is called santouri while the stationary type

with damper pedal, originally invented by Vencel József

Schunda (1808-1894) in Budapest in 1874, is called tsimbalo. Stélios

Keromítis (1908 -1979), one of the pioneers of Piraeus

rembetica and exclusively a bouzouki player, said in a radio interview

in the 1970s that the most perfect instrument for his music was the

tsimbalo. The instrument was an integral component of an oft-recorded

line-up consisting of lead singer, tsimbalo, mandola, guitar and violin.

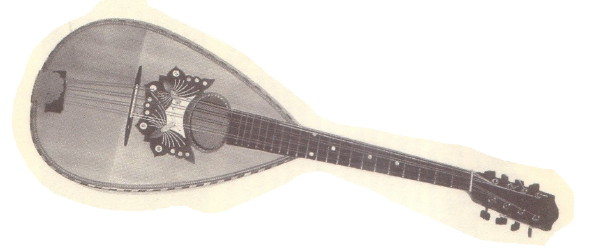

Mandolin

#12

Mandola

# 4? 9, 15, 17, 19

The bowl-backed Neapolitan mandolin in its modern form, with four

unison pairs of metal strings tuned in fifths, was established as such

by the middle or end of the 1800s, though the instrument had first

appeared around 1750.

The Estudiantina ensemble, with mandolins, guitar and markedly

Italianate singing, completely divested of Oriental elements, figures

among other Greek language recordings made in Asia Minor before 1920 (see

the CD 'Smyrni Me Ta Perihora'). The mandolin was also played in

the Athenian 'kantadha' ensembles in their Italianate serenades.

The mandola as used in the music of this period was a larger deeper

Neapolitan-style mandolin made in different sizes. It seems to have

been used exclusively as an ensemble instrument - this writer is not

aware of any true solo recording. In its largest version, the

mandoloncello, it can be heard on some Dalgas sides.

More advanced technical facility on instruments of the mandolin family

in recorded Greek music seems to antedate recorded virtuosity of an

idiomatic kind on the bouzouki by a decade or so. On this CD you may

get some idea of this by comparing the mandolins on track 12 with the

bouzouki on track 3. Admittedly, only three years separate these

particular recordings, but the 1905 Constantinople mandolin recording

mentioned above demonstrates at least the same technical level as that

heard on track 12. A comparable technical level on the bouzouki is not

to be heard on disc until 1932. An important reservation must be made

here. We are talking of recorded music; because they were not welcome

in studios, that does not mean there were no accomplished bouzouki

players earlier on. If musicians like Vamvakáris and

Keromítis could talk with reverence about a Manétas -

then what do we know? Even if many stories of persecution and

stigmatisation of bouzoukis and their masters are patently exaggerated,

there are fragments of genuine evidence that the bouzouki was, in one

way or another, 'persona non grata' for a long time.

When talking of pure virtuosity on the mandolin, it must be said that

some of the recorded Italians of the period far outstrip any of their

Greek colleagues. Comparable virtuosity on the bouzouki was first to be

recorded later in the 1930s with the playing of Vassílis

Tsitsánis - who in fact started on mandola - and Manólis

Hiótis, the latter still in his teens at his debut. Players

of the mandolin and mandola do not seem to have received the same kind

of attention and formal recognition as players of other 'default'

instruments of this period, and have, with the exceptions of Peristéris,

Toúntas and Dávos in Greece, and Ierothéos

Schízas in the USA, apparently remained nameless.

Notwithstanding, the mandolin and mandola are to be heard on a fair

number of recordings, notably those of Dalgás, Ríta

Abadzí, Róza Eskenázi and Stellákis

Perpiniádhis, and the mandola is also to be heard doubling the

melody on some of Papadzís' instrumental accordion tracks. The

presence of the mandola has been consistently underestimated in

otherwise perceptive annotations to reissues of this music. The sound

and balance of an ensemble on record is of course the result of choices

made by producers and recording engineers, even when using single

microphone technique. The mandola is often in the background and is

sometimes so discreetly placed that one might both wonder if it was at

all audible with the conventional sound reproduction of that time, and

whether it was always meant to be heard! There are recordings where the

mandola only plays behind the vocalist, doubling the melody line almost

as a guide or prompter. Occasionally it plays the foreground

introductory phrases later assigned to the bouzouki. One possible

reason for the paucity of credits for mandolin and mandola players in

recording company files might, in the light of these observations, be

that the studio director and musician are in certain cases one and the

same person, who doesn't see the need to be mentioned as he is already

being paid to direct the recording.

It is worth mentioning that Stellákis Perpiniádhis, when

selecting his favourite recordings for the LP reissue 'Autoviographia'

during the 'rembetica revival' of the 1970s, chose recordings featuring

mandolin, mandola, guitar, violin, accordion and santoúri, and

the unique instruments played by Iován Tsaoús, but chose

no true bouzouki. loánnis Papaioánnou - a famous

singer-bouzouki player-songwriter not represented here - gave mandola

as his metier on an official document, though we only have recordings

of him playing bouzouki. What we don't know is whether

Papaioánnou mentioned the mandola because the bouzouki was not comme

it faut in official situations. Furthermore, some early bouzoukis

of the period had a mandola body construction with the characteristic

shallow convex angle in the sound-board just behind the bridge. This

characteristic later disappeared from bouzouki construction.